2 Publications on Reuse

Architecture Books – Week 50/2025

This newsletter for the week of December 8 looks at two recently published publications focused on reuse in architecture. Fittingly, the book from the archive is about upcycling in architecture, while the usual headlines and new releases are in between. Happy reading!

Books of the Week

When I think back to architectural practice circa 2000, it seems that embracing sustainability and pivoting to designing buildings that used fewer resources and energy was a struggle, anything but an easy pill to swallow, particularly for clients. A couple decades later, the widespread embrace of adaptive reuse—predicated on the simple fact that demolishing buildings and building anew too much resources and energy—seems easy by comparison. Today, many architectural projects begin with the question: can the existing building (if there is one) be saved, reused? Given this trend, which I hope is more than just a trend, numerous publications about reuse in architecture are being published. Here I touch briefly on two of them: one an academic journal and one a book focused on the reuse of architectural components.

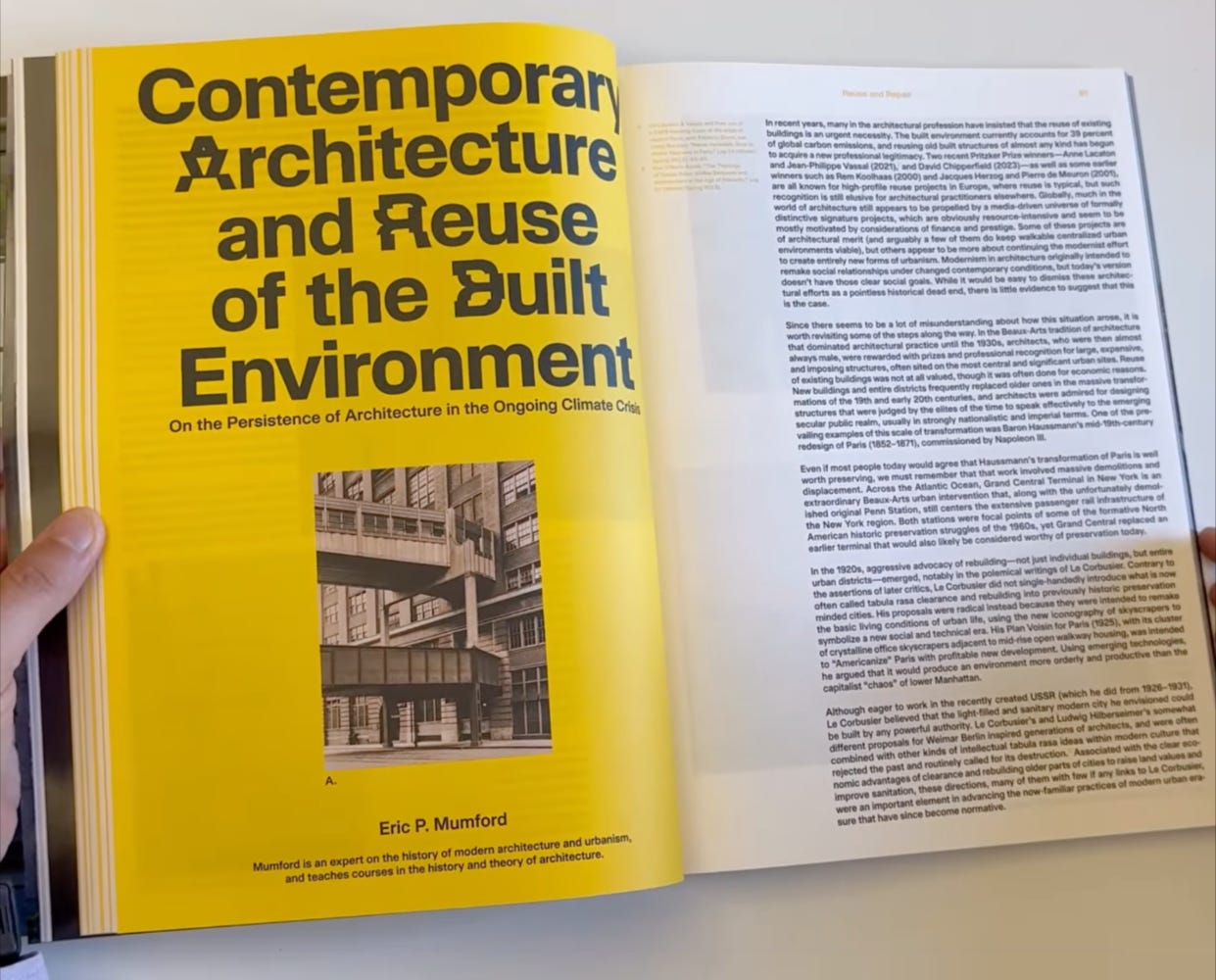

Harvard Design Magazine No. 53: Reuse and Repair, edited by Jeanne Gang and Lizabeth Cohen (Buy from Harvard GSD)

As I wrote earlier this year when reviewing Harvard Design Magazine No. 52: Instruments of Service, guest edited by Elizabeth Bowie Christoforetti and Jacob Reidel, “Over its more than 25 years, HDM has gone through numerous iterations, marked by changes in size, design, and content.” One consistency of its post-pandemic existence, not in place in its two decades before that, has been each biannual issue featuring guest editors who define a theme and solicit contributions from within and beyond Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, or GSD. For the latest issue, No. 53: Reuse and Repair, the editorial duties are split between Jeanne Gang, founder of Studio Gang and Kajima Professor in Practice of Architecture at the GSD, and Lizabeth Cohen, a historian who is the Howard Mumford Jones Research Professor of American Studies at Harvard.

The issue’s theme is very much aligned with the work of Studio Gang, whose latest monograph, titled The Art of Architectural Grafting, defines an approach to architectural design that elevates the importance of the existing and sees it as a canvas for reuse, adaptation, and/or extension. The firm, headquartered in Chicago but with offices in New York, San Francisco, and Paris, still partakes in new construction (especially towers), but an increasing number of recent projects fall into the “grafting” approach. Among them are the Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts, the Richard Gilder Center at the AMNH, the Beloit College Powerhouse, and the University of Kentucky Gray Design Building. Refreshing among these projects is the formal variety that stems from finding the right approach in merging the program and the existing building.

A similar variety can be found in the eighteen contributions spanning 246 pages of HDM No. 53. “Offering ‘reuse and repair’ as a pair of concepts to encourage thinking around how systemic change might be enacted,” the editors write in their introduction, “we aim to open a conversation about how designing toward a low-carbon future can go hand-in-hand with the wider work of caring for and remaking our cities and society.” As found in its pages, shat conversation spans from obsolescence, rebuilding after disasters, and the relationship between race and space, to concrete brutalism and the war in Ukraine. Some contributions are literal conversations: roundtables about reuse in architecture schools, a second life for a temporary pavilion in Chicago, and the LA wildfires, among them.

There are many highlights, though I’ll just point out just a few: David Gissen and Georgina Kleege’s piece, “The Glass Hospice,” which draws attention to the changes Philip Johnson made to his Glass House near the end of his life for accessibility, but which the National Trust for Historic Preservation has erased from reality since; Brian D. Goldstein’s portrait of J. Max Bond Jr. (the Bond of Davis Brody Bond); Roberto Fabbri piece on the heritage of mid-century architecture in the Gulf region; and the closing piece on DnA’s stunning Huangyan Quarries, with words by Shirley Surya and photos by Tian Fangfang.

I also want to note the issue’s design, which is commendable for the playfulness found in its AM Reverse typeface and its page layouts, but which is also, unfortunately, unreadable at times. Yellow on black, as in the spread above, is fine, but yellow on white, as in the footnotes in the margin in the spread above that one, is not—straining to read in anything but the brightest of lighting conditions. Elsewhere, some white captions on full-bleed photos can’t be read over the noise of the photos, and one of the subtitles to an article literally disappears, due to it being gray text on a gray concrete background. While the footnotes are prevalent, the other readability issues are thankfully infrequent, thought I attribute all of them to the prevalence of designers working on screen and not considering how things will “read” once printed.

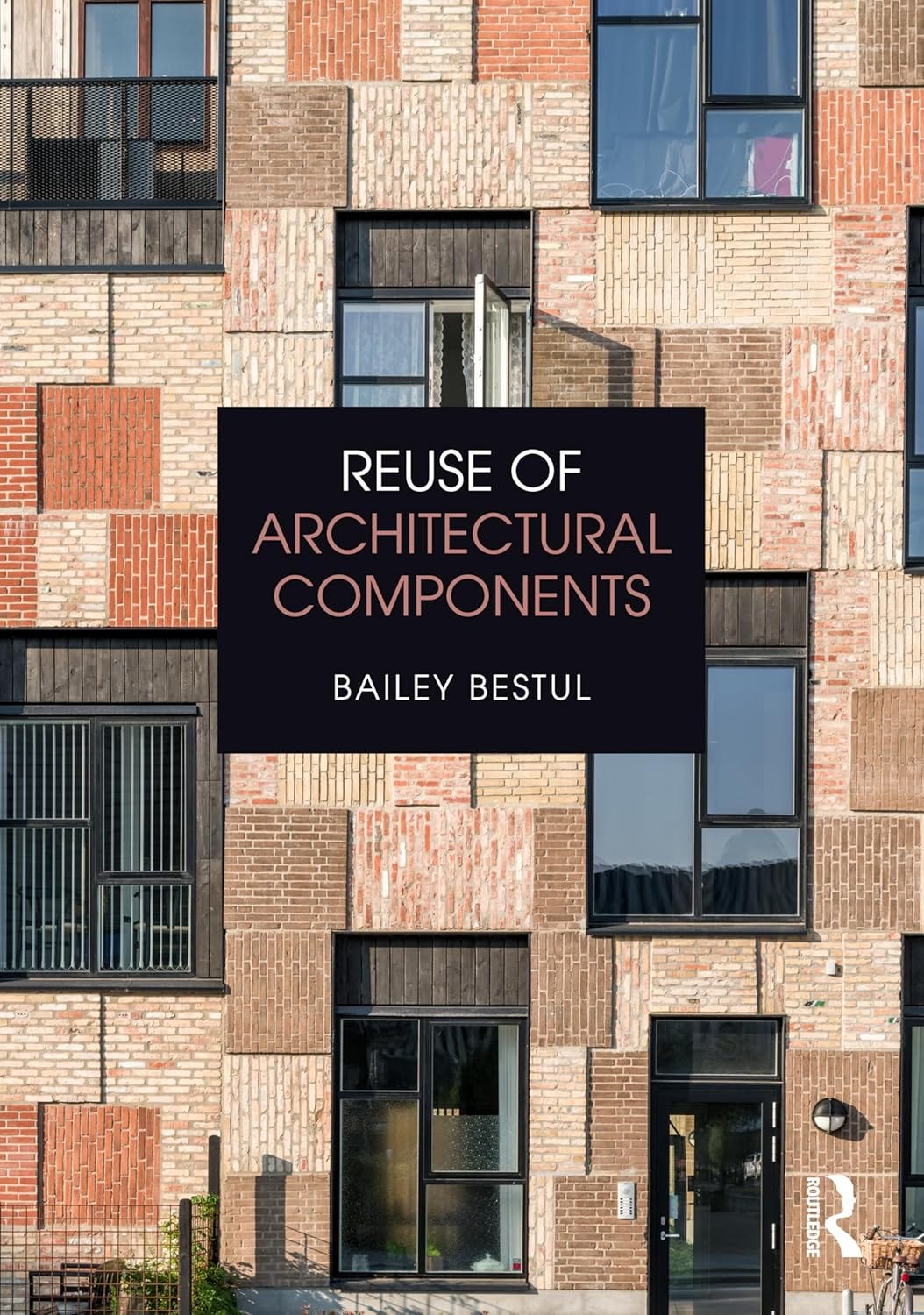

Reuse of Architectural Components, by Bailey Bestul (Buy from Routledge / from Amazon / from Bookshop)

If a book can be judged by its cover, the second title focused on reuse is about architectural creativity in materials and finding beauty in the (sometimes literal) patchwork results that come from working with components harvested from older buildings rather than produced anew. The project on the cover of architect Bailey Bestul’s Reuse of Architectural Components is Resource Rows, an apartment building in Copenhagen designed by Lendager with brick facades made from dismantled buildings. As Bestul explains in the chapter “The flexible design,” the cement mortar used in the old buildings made it hard to take their facades apart brick by brick, so they were cut apart as slabs and lifted onto the new building as panels that could be oriented in different directions, not the typical horizontal bonds of bricks. Architects with some knowledge of modern architectural history will no doubt see the project’s resemblance to Alvar Aalto’s Muuratsalo Experimental House, which similarly composed brick panels in quilt-like arrangements. So Lendager’s idea was not new, but it is evidence that Aalto’s experiment found larger application—and a low-carbon means of construction—a half-century later with Resource Rows.

Resource Rows is just one project among dozens discussed by Bestul across nine chapters, each one looking at different strategies and concepts for material reuse across different stages of the architectural and building process: planning, assembly, and finishing. But his book is not a survey, a presentation of architectural projects. It is a discussion of the various approaches architects can take in designing buildings that incorporate reused components. The projects are like pearls on the thread of his discussion—exemplary examples and illustrations of a particular take on reuse. Of the many projects, quite a few were drawn from the Venice Architecture Biennale—a fitting venue, given that architectural innovation should be on display there, if anywhere, and concerns over waste in architectural exhibitions have pointed toward salvage and reuse rather than trashing or recycling materials. There are also quite a few European buildings, though I chalk this up to the author’s Fulbright Scholarship enabling him to study the circular economy for building materials in the Netherlands. Today, the reuse of architectural components is a worldwide trend.

Beyond the projects, quite a few of which I was not familiar with before cracking open the book, the value of Bestul’s book is found in the concepts he proffers for material reuse, each of which is used to structure the nine chapters. A few of them include “Palliative architecture,” a surprising yet apt term for maintaining dying pieces; “Thick architecture,” which sees opportunity in the oversized pieces shifted from a larger project to a smaller one; and “Dirty, icky, yucky architecture,” or finding beauty in residues of past uses. These concepts also show the subtle playfulness of the book, echoing the sometimes playful architecture on display.

Books Released This Week

(In the United States; a curated list)

Bruce Goff: Material Worlds, edited by Alison Fisher and Craig Lee (Buy from Yale University Press [distributor for Art Institute of Chicago] / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “A major exploration of the work of American architect Bruce Goff, including the paintings, objects, and ephemera often overshadowed by his architectural legacy.”

Vitra: The Anatomy of a Design Company, by Deyan Sudjic, with contributions by Karen Stein and Iwan Baan (Buy from Phaidon / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “The in-depth story of one of the world’s most innovative and influential design companies.”

Contemporary Architecture in Saudi Arabia, by Christopher Masters (Buy from Merrell / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “The first building-by-building survey of the remarkable architectural achievements in Saudi Arabia over the last fifty years, featuring case studies of 45 outstanding projects as well as previews of buildings due for completion by 2030.”

Kengo Kuma: Substance, by Kengo Kuma and Associates (Buy from ACC Art Books [US distributor for Images Publishing] / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Kengo Kuma: Substance explores the work of the acclaimed Japanese architect through six materials—wood, bamboo, metal, paper, textile, and stone—and presents the ideas behind each work.”

updn: 88 Spins with Bill Pechet, by Leslie Van Duzer (Buy from ORO Editions / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Neither an architect nor a landscape architect, Pechet might best be described as an urban acupuncturist.”

Buildings by Women: Rotterdam, by Sofie van Brunschot, Catja Edens, Laurence Ostyn and Erica Smeets-Klokgieters (Buy from Artbook/DAP [US distributor for nai010 Publishers] / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “See Rotterdam from a new perspective: through the eyes, minds and hands of the women architects who helped build it.”

What’s Next for Mom and Dad’s House? Essays on the Single-Family Housing Type and Its Future, vol. 1, edited by Martino Tattara and Federico Zanfi (Buy from Artbook/DAP [US distributor for Spector Books] / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Proposing solutions for how the traditional suburban single-family house can be reinvented for the contemporary market and climate.”

Homes For Our Time: Small Houses, by Philip Jodidio (Buy from Taschen / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Including the work of Alphaville, Olson Kundig, BIG, Aranza de Ariño, Takeshi Hosaka, and MAPA, this diverse collection of small but delicate houses proves that 100 square meters is plenty of room for intelligent and responsible living. Dream big—build small.”

The Architect and the Animal, edited by Kostas Tsiambaos (Buy from MIT Press / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “A spirited abecedarium-style book that shows how architects have engaged with animals as references and metaphors in modern and postmodern architecture.”

Full disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, AbeBooks Affiliate, and Bookshop.org Affiliate, I earn commissions from qualifying purchases made via any relevant links above and below.

Book News

The latest post from Machine Books presents “a round up of our interviews with key authors in 2025; the people who wrote the best books about architecture this year.”

Misfits Architecture’s post on Japan’s Nikken Sekkei is worth reading for, among other things, the scans of a few spreads from Encyclopedia of NIKKEN, the special issue of A+U from earlier this year devoted to the large practice.

If you’re in New York City, on Wednesday evening the bookstore HEAD HI is hosting a presentation of Moving Mountains, a new book featuring the architecture of Carl Fredrik Svenstedt Architects, the Paris-based studio specializing in architecture made with stone.

Phaidon, which owns Monacelli Press, Robert A.M. Stern’s longtime publisher, has a tribute to Stern, “the classicist who built the future.”

Canadian Architect has the first installment in its year-end round-up of “this year’s best books for Canadian architects and lovers of design.”

Wallpaper* has a lengthy guide “to the best new architecture books - from meaty monographs to themed explorations and lots of immersive visuals.”

Not to be confused with the list of the best books on architecture they published two weeks ago, the Financial Times has a roundup of “2025’s best books on interiors and architecture.”

Most readers know that Frank Gehry, a giant in architecture, died last week at the age of 96. On my old blog, I had reviewed some Gehry books, including Jean-Louis Cohen’s Frank Gehry: The Masterpieces and Frank Gehry: The Houses by Mildred Friedman, and I took screenshots of his appearance on The Simpsons back in 2005. And over the weekend I posted photos from a rare Gehry publication in my library to Instagram:

From the Archives

Of the hundreds of book reviews on my blog, the one most relevant to this week’s Books of the Week is Upcycling: Reuse and Repurposing as a Design Principle in Architecture, which was edited by Daniel Stockhammer and published by Zurich’s Triest in 2020. Here’s the text from my 2021review:

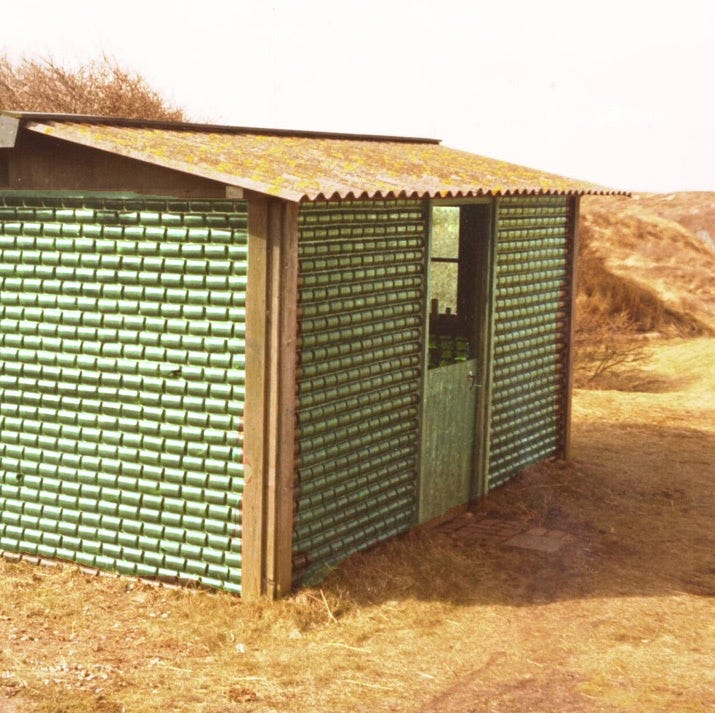

The cover of Martin Pawley’s 1975 book Garbage Housing features a grainy photograph of a house on a yellow background, with the house positioned above a collage of cans, bottles, and other detritus. Although the house looks conventional, with a gabled form and square window, the textured walls—not to mention the title of the book—hint at something exceptional. The house is actually Alfred Heineken’s WOBO house that was designed a decade earlier by architect N. John Habraken with beer bottles he devised for Heineken, bottles that could be “upcycled” from holding beer to holding up the roof of a house. Habraken designed the bottles with concave bottoms (much like wine bottles) that enabled the bottles to be nested in rows and then stacked like bricks. One hundred thousand WOBO bottles were manufactured but just one such house, in Heineken’s own garden, was built from them, a victim of corporate marketing.

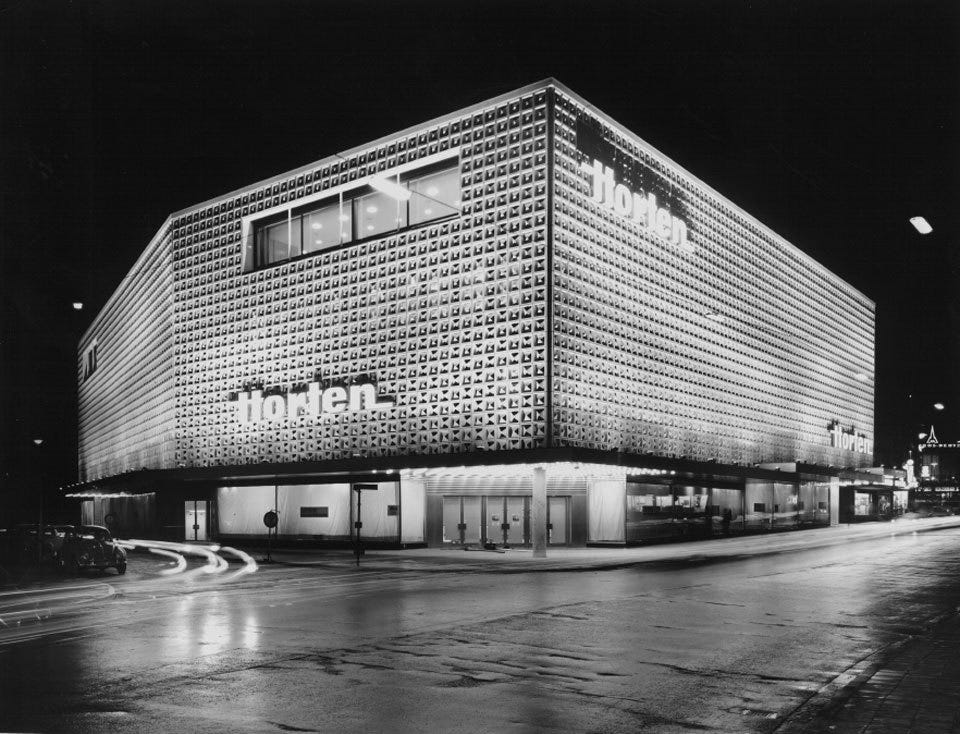

In 1966, just a couple years after Heineken’s WOBO house, the Horten department store, designed by Rhode Kellermann Wawrowsky (RKW), was built in Hamm, Germany. The outer layer of the store was covered in molded aluminum tiles that gave the building its modern, textured appearance. Fast forward to 2007 and the unfortunate demolition of the 41-year-old department store: fortunately, many of the Horten tiles were saved and sold for reuse. KARO* architekten worked on one project (the only one I’m aware of) that reused the tiles: the award-winning Open-Air Library located in “a socially depressed” area of Magdeburg, Germany. Previously the library on the same site was temporary, made from milk crates. With the Horten tiles, the Open-Air Library became permanent, another example of “upcycling” a material, or in this case a component.

Both of these examples of upcycling are found, appropriately enough, in Upcycling, which looks at historical and recent examples (almost exclusively in Europe, especially German-speaking countries) of materials being reused in ways that does not downgrade their physical makeup or their architectural potential. It is an optimistic, if academically grounded book whose message even extends to its cover; the second edition, which the publisher sent me, is recycled “Gmund Bio Cycle made from fast growing fibers and green waste.” If Pawley’s 45-year-old book on “garbage housing” put the image of such on its cover, this book makes its subject into the cover.

Inside the book are a dozen contributions in two sections: “History of Reuse and Repurposing” and “Reuse and Repurposing of History?” They follow editor Daniel Stockhammer’s excellent introduction, which highlights the increasing attention given to adaptive reuse and other ways of preserving materials over the long-held focus on new buildings valued for formal innovation. It’s a refreshing shift toward an approach that has been done for centuries, as the examples in the book show, but is being discussed more and more as climate change and resource scarcity increases. More than having a firm grounding in issues of sustainability, adaptive reuse and examples of upcycling should be seen as impetuses for creativity: the layering and collision of old and new should be enthusiastically embraced by architects, not just forward-thinking clients like Alfred Heineken. This book offers a myriad of examples, from both academics and students, that should intellectually inspire architects interested in an upcycling design approach.

Thank you for subscribing to A Weekly Dose of Architecture Books. If you have any comments or questions, or if you have your own book that you want to see in this newsletter, please respond to this email, or comment below if you’re reading this online. All content is freely available, but paid subscriptions that enable this newsletter to continue are welcome — thank you!

— John Hill

Excelent roundup showing how reuse has shifted from marginal practice to architctural mainstream. Bestul's taxonomy is sharp, especialy "Palliative architecture" which reframes maintainence as creative intervention rather than just preservation. What's intresting is how Resource Rows inverts the usuall hierarchy, the constraint of cutting brick panels becomes the aesthetic driver, making neccessity legible instead of hiding it.