This newsletter for the week of March 17 takes a look at a book by Japanese architect Kengo Kuma that was recently published by Thames & Hudson. The book, Point Line Plane, prompted me to dig out an old book of essays by Kuma and look at a monograph on one of Kuma’s favorite architects. The usual new releases and headlines are also here. Happy reading!

Book of the Week:

Point Line Plane, by Kengo Kuma (Buy from Thames & Hudson / from Amazon / from Bookshop)

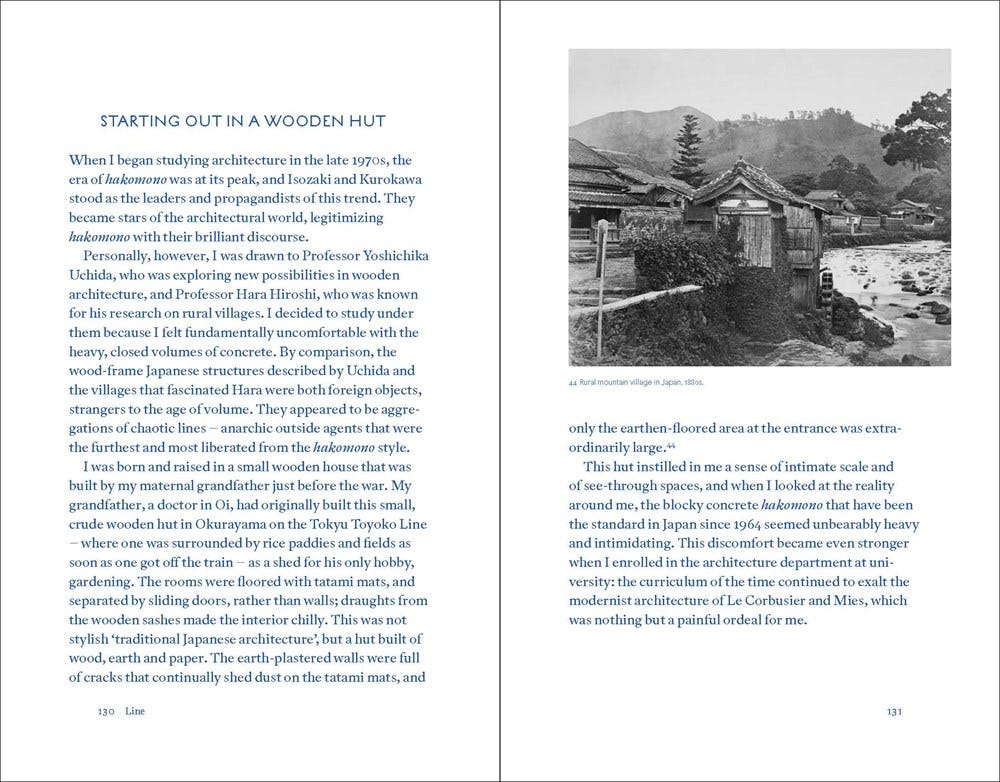

Clearly Kengo Kuma does not like concrete. One could come to this conclusion by looking at the Japanese architect’s website or monographs, which are full of projects in timber, stone, metal, and other materials that are not concrete. Kuma has also articulated this distaste explicitly in his writings. In the foreword to his latest book, Point Line Plane (originally published in Japanese in 2020, it was translated into English and released by Thames & Hudson last October), he references his earlier book Architecture of Defeat (see the bottom of this newsletter), writing: “The 20th century was a period of ‘victorious architecture’—buildings that employed the hard, strong, heavy material of concrete as a means of defeating the environment.” As an alternative, he proposed the concept of “defeated architecture.” This concept comes across in his buildings through small-scale elements—shingles, slats, tiles, frames, etc.—that are the antithesis of the reinforced concrete walls that are prevalent in the buildings of other architects, in Japan and elsewhere.

This doesn’t mean Kuma does not want to build big. As Kuma writes in the introductory chapter to Point Line Plane, “A Discourse on Method,” he appreciates an architecture “in which the ultra-small and the ultra-large are layered.” But a reliance on concrete—along with steel, the default material for building big—leads to an architecture of volumes, in Kuma’s words, though he prefers architecture of points, lines, and planes. Inspired by science, these building blocks of architectural form are not separate; they are intertwined, like the vibration of strings in string theory. The book’s purpose, he writes at the conclusion of the first chapter, “is not to classify points, lines and planes as such, but on the contrary, to make it clear that points, lines and planes are all vibrations and manifestations thereof, and thus can never be truly divided into separate categories.”

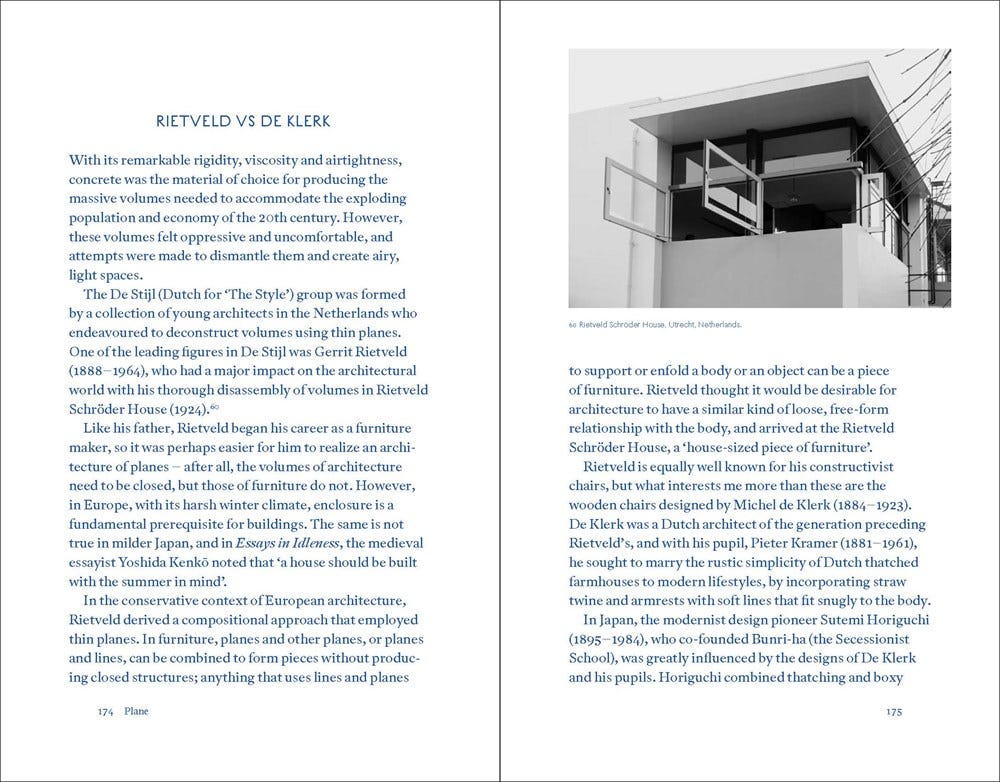

Nevertheless, the three chapters that follow “A Discourse on Method” are “Point,” “Line,” and “Plane.” Each of these chapters is comprised of roughly a dozen to two dozen short essays, each one with a specific subject and/or assertion, but all flowing together into a consistent narrative. Still, each chapter has an arc, moving from influences from architectural history and from fields outside of architecture, such as science, to specific examples culled from Kuma’s increasingly diverse and prolific output. So the “Point” chapter looks at Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram Building “as an aggregation of points,” Filippo Brunelleschi’s “inductive architecture,” and the difference between traditional roof tiles in Japan and China before discussing Kuma’s own Stone Plaza (2000), Water Branch (2008), and the Folk Art Museum at the China Academy of Art (2015). Illustrations in this small-format (6x9”) book are few (71 across 210 pages) and in black and white rather than color, so the book’s value is found in Kuma revealing where he finds his ideas and how he applies them to his architecture, not in presentations of the buildings themselves.

There is a lot to commend in Point Line Plane, which I found to be a smart and enjoyable book. Through clear, conversational text, Kuma is able to explain the bases for his architectural ideas, rooting them in the lineage of both modern and traditional architecture, and he illustrates how his buildings stand apart from his contemporaries, both within and outside Japan. Although the recent embrace of Brutalism has found a backlash in the Trump administration’s attempts to require neoclassical and other traditional styles in the United States, Kuma’s architecture shows that there are other, progressive alternatives to large concrete surfaces. Arguments for neoclassical architecture often point to the general public’s preference for it as gauged by surveys and to findings in neuroscience that link concrete walls and other unadorned surfaces to anxiety. Kuma’s richly patterned buildings in wood, stone, metal, and even plastic fit neatly within the latter, pointing to ways architecture today can be enriching yet also cognizant of science, technology, and other parts of the contemporary world.

Books Released This Week:

(In the United States, a curated list)

A. Lawrence Kocher: American architect, by Luis Pancorbo and Inés Martín Robles (Buy from Applied Research + Design / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Kocher’s work as an independent designer has gotten very little critical attention. The book devotes several chapters to this little-known part of Kocher’s practice and resituates him as one of the main protagonists in the history of American Modern architecture and reveals the profound relationship between Kocher’s designs and existing American domestic traditions.”

Episodes in Public Architecture, by Andrew Frontini (Buy from ORO Editions / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Architect Andrew Frontini converts the architectural monograph into a story telling vehicle to candidly reveal the inner workings of the architect’s creative process as it intersects with the constantly evolving needs of our society.”

Tips from the Top: Architects Share Their Advice for Success, edited by Clifford Pearson, Ken Yeang and Raghda AlHayali (Buy from PA Press / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Tips from the Top is a collection of advice from more than sixty architects who have earned the respect of their peers and are willing to share their knowledge on building a successful and meaningful career in architecture.”

Wit-ness to Mat-Haroo, by Vagish Naganur and Gurjit Singh Matharoo (Buy from ORO Editions / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “ Witty True-life Incidents from an architect’s Professional life with bizarre endings narrated in a satire short story form.”

Full disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, AbeBooks Affiliate, and Bookshop.org Affiliate, I earn commissions from qualifying purchases made via any relevant links above and below.

Book News:

Wallpaper* looks at the updated verison of Christopher Rawlins’ 2013 book Fire Island Modernist: Horace Gifford and the Architecture of Seduction that will be released next month.

STIR World delves into Archigram Ten, Peter Cook’s “fervid vision of a contemporaneous future.”

Also at STIR World is one of many recent pieces exploring the design underlying Severance, though Mrinmayee Bhoot relates it to many books, from classics by Henri Lefebvre, Aldous Huxley, and Nicholas Barker to Beatriz Colomina's X-Ray Architecture and Shoshana Zuboff's The Age of Surveillance Capitalism.

From the Archives:

On page 185 of Point Line Plane, Kengo Kuma refers to his principle of “architecture of defeat,” mentioning it in the context of the Teehaus he designed for the Frankfurt Museum of Applied Arts. Outside of this page and the foreword mentioned in my review of the book at the top of this newsletter, he does not expound on the phrase that was the title of a collection of Kuma’s essays published in English by Routledge in 2019. Although Architecture of Defeat appeared a decade and a half after it was first published in Japanese, I found the essays to still hold relevance, writing in my 2019 review how “Kuma tends to write about architects and buildings in the past or about contemporary architecture and life in a way that is fresh and forward-thinking.” What about the title phrase? What is an “architecture of defeat”? Perhaps these lines from my review hold a clue:

“I was most impressed with […] Parts 1 and 3: ‘Disconnection, criticism, form’ and ‘Brands, virtuality, enclosure.’ Here Kuma treads into territory that gives the book its ‘defeat’ moniker, though unlike both the author and the publisher asserting that it is ‘an optimistic and hopeful book,’ I see it more as a course correction. Take the first essay in the book, ‘From disconnection to connection,’ in which Kuma looks at two strands of 20th century economics—policies promoting homeownership and Keynesian spending on large public projects—and how architecture was complicit with a widespread modernization that resulted in architecture being ‘the enemy of society.’ Seeing an ‘era of disconnection’ resulting from this process, he argues for ‘architecture as a matter of connections,’ though what form that would take is limited to discussion of natural materials over concrete.”

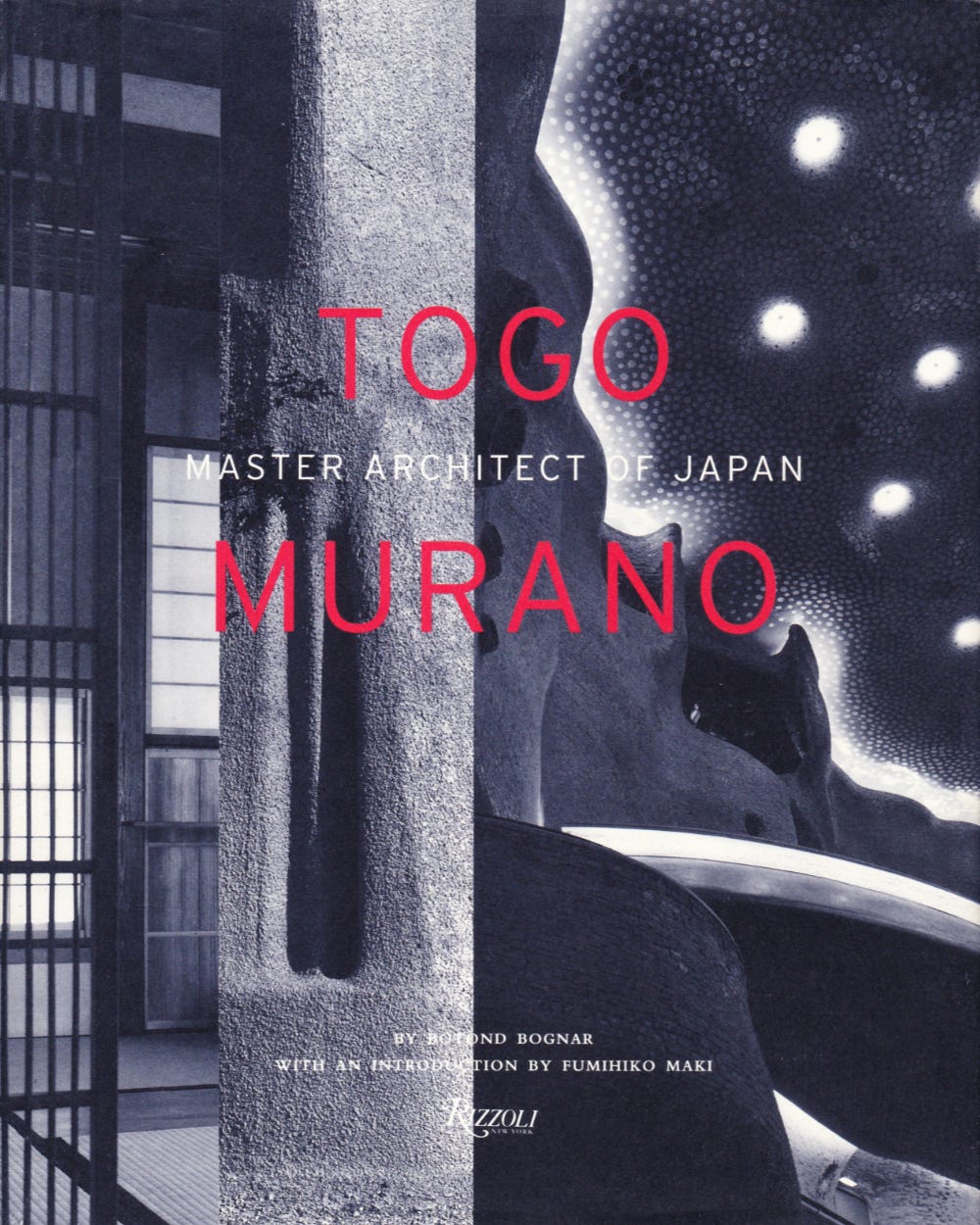

One of the architects that Kengo Kuma singles out in Point Line Plane as embodying similar principles to his own is Togo Murano. In the “Line” chapter, Kuma describes Murano as “pursuing fine lines in architecture,” and, unlike “modernist architects like [Kenzo] Tange [who] were interested only in the silhouettes of volumes,” Murano “continued to grapple with the varieties of points, lines and planes that contemporary materials made possible.” The best (only?) book in English for people interested in the architecture of Togo Murano is Botond Bognar’s Togo Murano: Master Architect of Japan, published by Princeton Architectural Press in 1996. The formal and tectonic diversity of Kuma’s architecture finds a parallel in how Bognar describes Murano: “He promoted an extraordinary variety of architecture and a versatility in modes of design,” such that “it is this freewheeling exuberance, the mobilization of the broadest possible range of architectural paradigms, that distinguishes his architecture more than anything else.” The book features 27 “major works” completed between 1931 and 1983, ranging from traditional structures that look like they were from another century to sculpturally expressive buildings that foreshadow some of the parametric architecture built in our current century. Unlike Kuma, whose international fame is expressed in the number of monographs devoted to him and the media presence accompanying the many buildings his firm completes every year, the thrift of books devoted to Murano points to him being unfairly overlooked, both in his day and our current age. Thankfully, Master Architecture of Japan is a beautifully produced document on an “idiosyncratic and eclectic” architect.

Thank you for subscribing to A Weekly Dose of Architecture Books. If you have any comments or questions, or if you have your own book that you want to see in this newsletter, please respond to this email, or comment below if you’re reading this online. All content is freely available, but paid subscriptions that enable this newsletter to continue are welcome — thank you!

— John Hill