This newsletter for the week of March 24 looks at a book covering an overlooked time in the career of Spanish-born architect Félix Candela, whose thin-shell concrete vaults in Mexico impress to this day. A couple books “From the Archive” at the bottom of the newsletter are related to this “Book of the Week,” while the usual headlines and new releases are in-between. Happy reading!

Book of the Week:

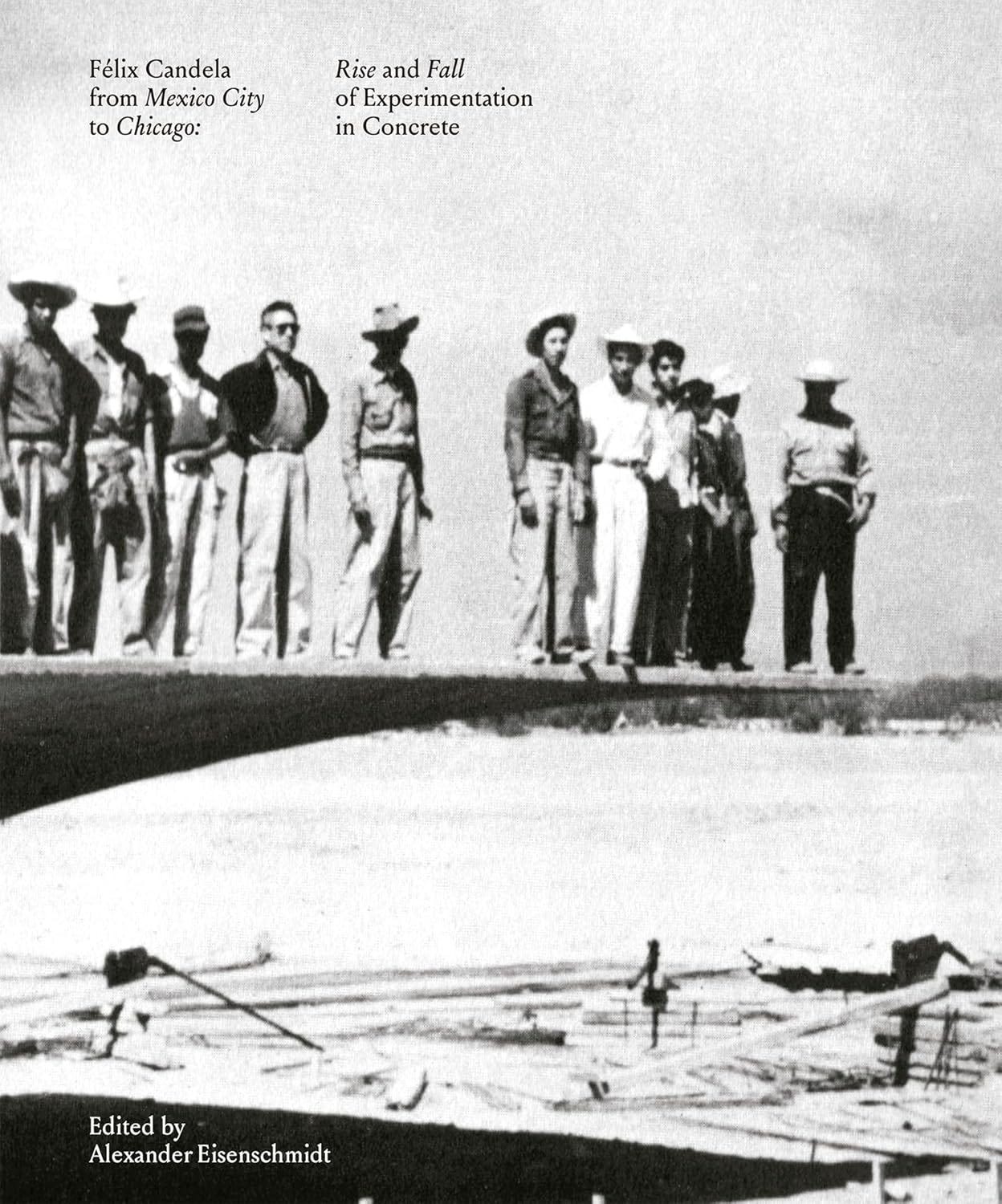

Félix Candela from Mexico City to Chicago: Rise and Fall of Experimentation in Concrete, edited by Alexander Eisenschmidt (Buy from Actar Publishers / from Amazon / from Bookshop)

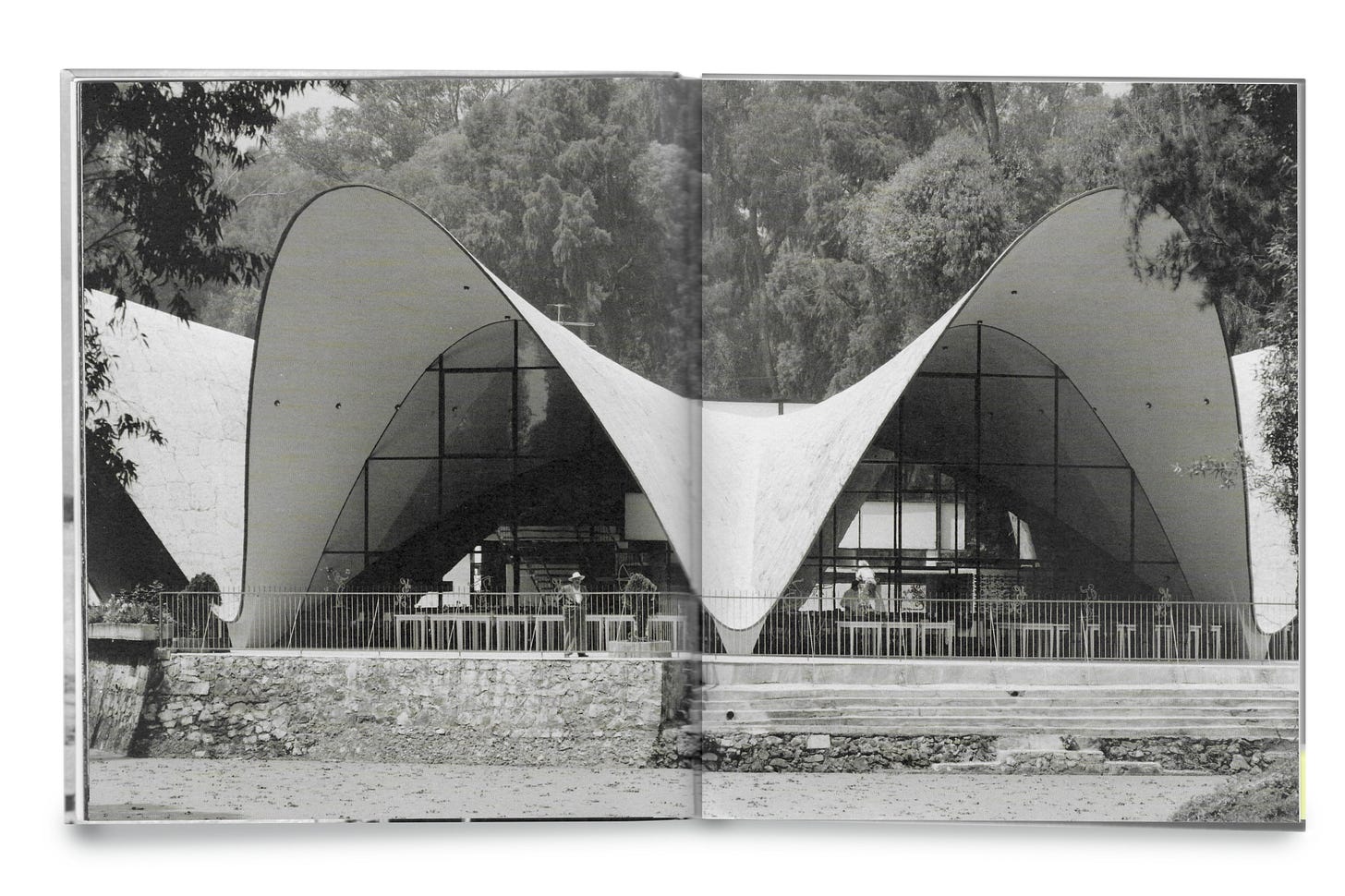

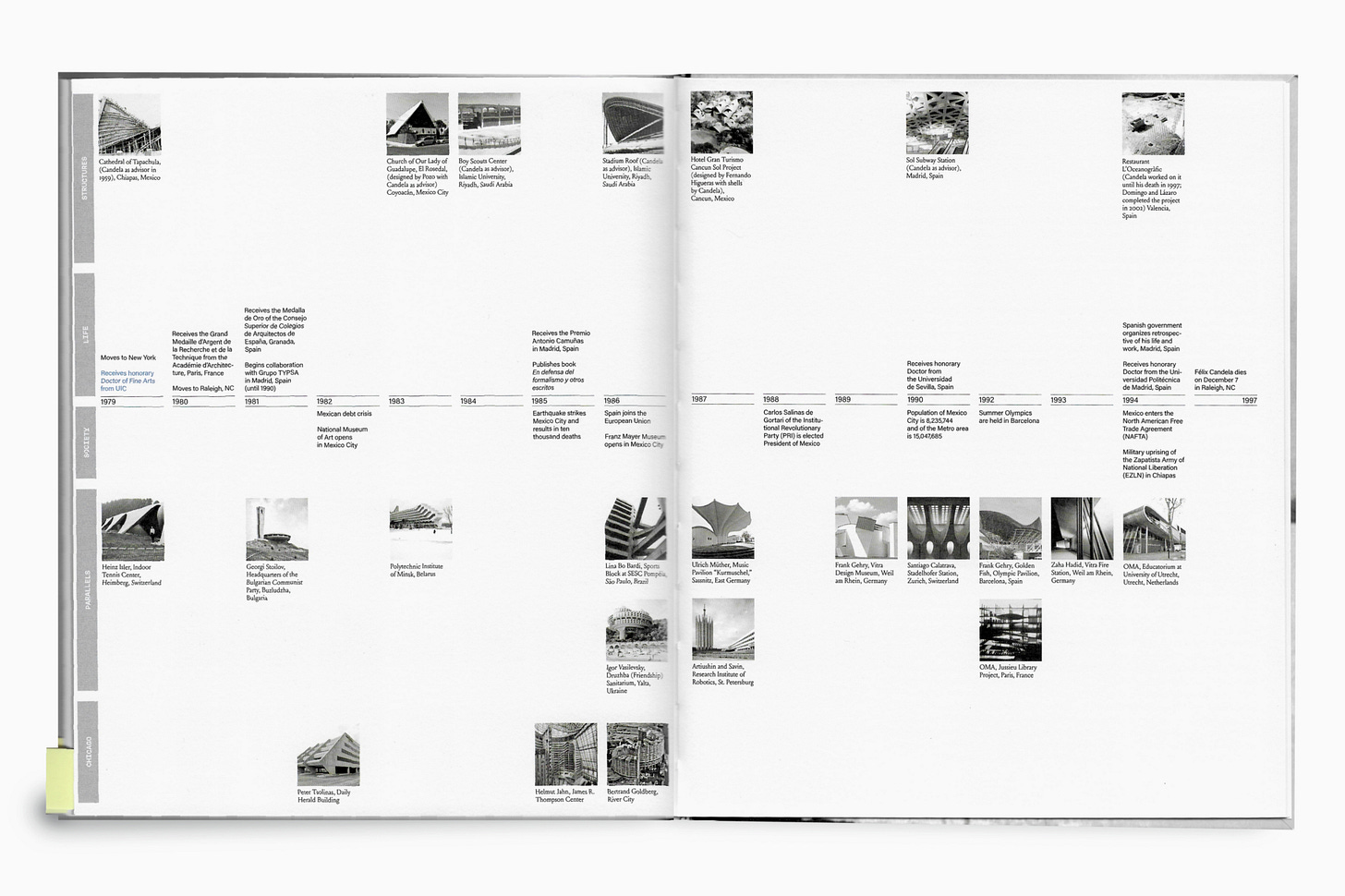

In 1963 the Reinhold Corporation published a monograph on Félix Candela (1910–1997), by Colin Faber, titled Candela: The Shell Builder. This introduction of the Spanish-Mexican architect-contractor-engineer to a wider United States audience neatly summed up his notable creations: the thin-shell concrete structures he had built in Mexico since the establishment of Cubiertas ALA (Wing Roofs) in 1949. But a decade after the book was published, when he was living, teaching, and trying to build in Chicago, Candela was disenchanted with his experimental forte and had folded Cubiertas ALA. As described by Alexander Eisenschmidt in this excellent study of Candela’s career in the US and Chicago in the 1970s, “the era of thin-shell concrete construction had passed.” How so? How could Candela’s highly productive practice shrivel to basically nothing in so short a time? And why, having constructed hundreds of structures in Mexico and other parts of Latin America, did he move to Chicago?

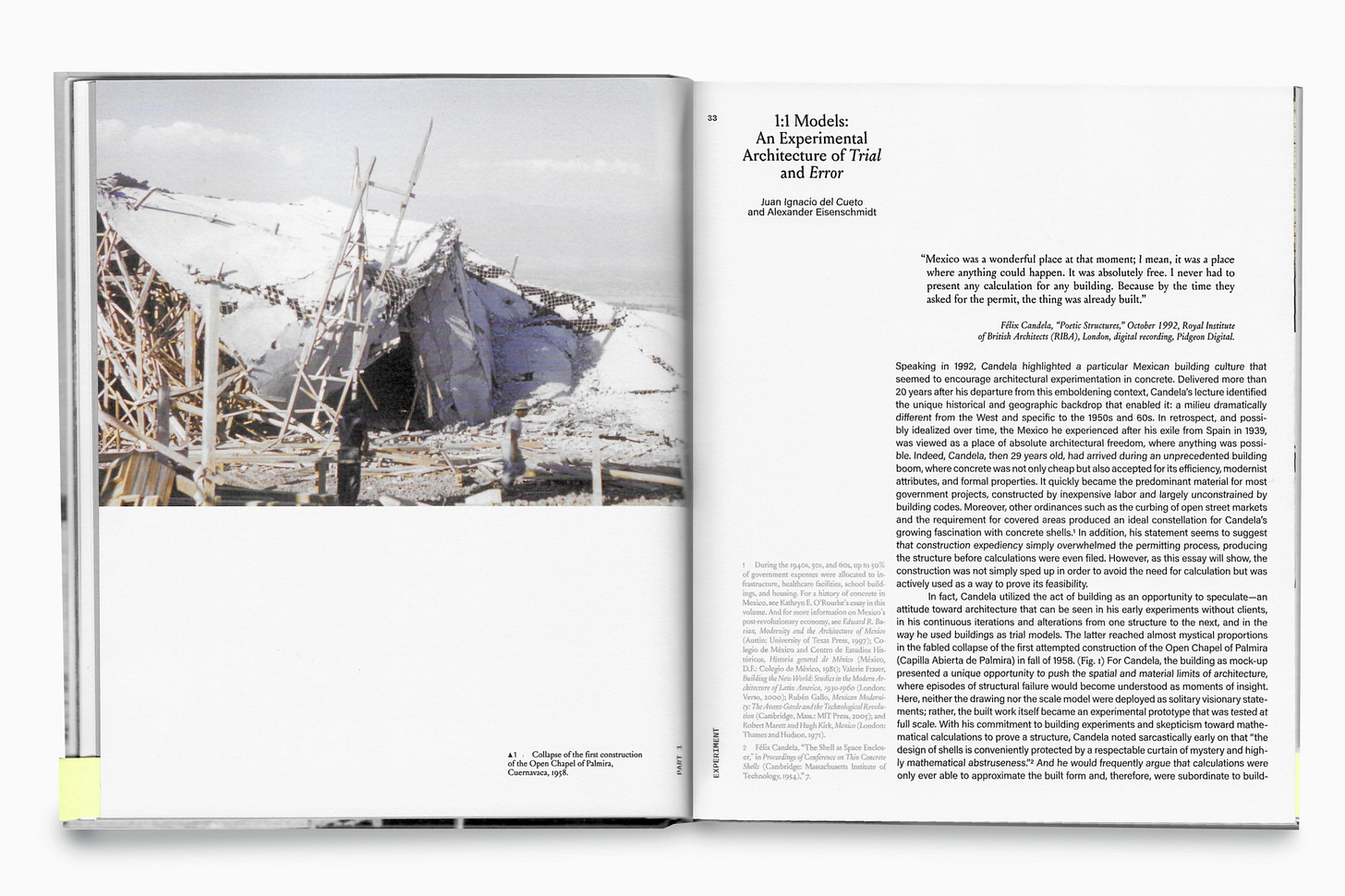

Many of the answers to these and other questions around this stage of Candela’s career are circumstantial, rooted in economic, social, and political situations in Mexico and the United States. Candela was an engineer and builder as well as an architect, meaning he was able to take risks—and take them at full-scale, as depicted in the photo of the collapsed vault in the below spread—with the construction of his thin-shell vaults. Candela was able to experiment in situ rather than via structural calculations and/or architectural drawings because, in Mexico in the 1950s and early 1960s, the labor laws were lax and the costs of labor were low, and his hyperbolic paraboloid (hypar) structures demanded a lot of manual effort for erecting the formwork and inserting the concrete. The minimum wage decree of 1964 and protests of 1968 respectively made Candela’s projects untenable and pushed him to consider moving to the United States. “While Candela did not write about these events,” Eisenschmidt states, “they clearly affected his position with regard to Mexico and his determination to leave the country.”

Candela ended up in Chicago in 1971 thanks to an invitation from Leonard Currie, dean of the College of Architecture and Art at University of Illinois at Congress Circle (UICC, now UIC, University of Illinois Chicago) to join the faculty. It must have been an ironic invitation, given that Chicago was known as a city of steel rather than concrete, but projects such as Bertrand Goldberg’s Marina City did find architects and contractors experimenting with concrete ahead of Candela landing there. Currie portrayed Chicago to Candela, Eisenschmidt writes, as “a willing territory for collaborative explorations in concrete.” But facing a socio-economic situation dramatically different than his heyday in Mexico—one where general contractors increasingly wielded power and the ghost of Mies was still strong—Candela was not able to make much of a mark in Chicago. Stanley Tigerman, who conducted an interview with Eisenschmidt in 2017, a couple of years before he died, and who had taught with Candela at UICC in 1971, described Chicago as “not very open to Candela’s ideas and ways of working.” Therefore “he never received the notoriety that I thought he should have had.”

Félix Candela from Mexico City to Chicago explores much more of what I touched on above, with half of its four chapters looking at his two decades in Mexico and the other half focused on his shorter time in Chicago, from 1971 until 1978. Eisenschmidt’s book balances new essays (by Eisenschmidt, Nader Tehrani, Geoffrey Goldberg [son of Bertrand], Robert Bruegmann, and others), interviews (with Tigerman, William Baker, Stuart Cohen, and Kenneth Schroeder), and archival texts (by Candela, Reyner Banham, Esther McCoy, Alvin Boyarsky, Carl W. Condit, and others) to provide a deeply researched history on an overlooked aspect of an influential, one-of-a-kind architect-builder-engineer. Although the page layout frustrated me at times—the footnotes in the margins are hard to read, the archival texts occasionally disappear into the fold, and many of the images are too small—as did the lack of an index, the texts are excellent, and the thorough illustrated timeline in the back of the book is a helpful addition to a valuable book of architectural scholarship.

Books Released This Week:

(In the United States, a curated list)

Brussels Housing: Atlas of Residential Building Types, by Gérald Ledent, Kristiaan Borret and Alessandro Porotto (Buy from Birkhäuser / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — The expanded edition of “this publication analyses 121 selected examples illustrating the emergence of the terraced house [in Brussels] and its further development in other forms of housing. The result is a broad panorama and a history of the architecture and development of the city of Brussels with its particularly heterogenous cityscape.”

Isay Weinfeld Works, by Isay Weinfeld, edited by Oscar Riera Ojeda (Buy from Rizzoli / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “A comprehensive consideration of the architecture and interiors of the great contemporary Brazilian architect, designer, and filmmaker. Featured projects span four decades in the architect’s ongoing quest for beauty and his deeply felt devotion to modernist principles.”

Full disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, AbeBooks Affiliate, and Bookshop.org Affiliate, I earn commissions from qualifying purchases made via any relevant links above and below.

Book News:

Artist Stéphanie Baechler’s Forget Me Not, a book about 19th-century textile-drying towers in Eastern Switzerland, won the highest honor in Stiftung Buchkunst’s Best Book Design from all over the World 2025 competition. I wrote about it for World-Architects.

Over at Architect, Aaron Betsky reviews Todd Gannon’s Franklin D. Israel: A Life in Architecture, recently published by Getty Publications. (I’ll have a review of the book in this newsletter next month.)

Derek Krissoff's Book Work newsletter has a quick take on Meta using pirated books, via LibGen, to train its AI program. For deeper reading on LibGen, click on the gift link to The Atlantic in Kirissoff’s post.

Over at MAS Context, Elizabeth Blasius travels to Rogers City, Michigan, to “check out” Presque Isle District Library’s restoration of Rogers Theater, a historic single-screen movie theater.

Read Women Writing Architecture’s interview with Mariana Siracusa of Spazio, the bookstore and gallery she founded in Milan in 2017.

Over at Crime Reads, author Gigi Pandian briefly describes five mystery novels that employ “architectural misdirection, giving the reader puzzles that are elevated through devious architecture at the heart of each story.”

From the Archives:

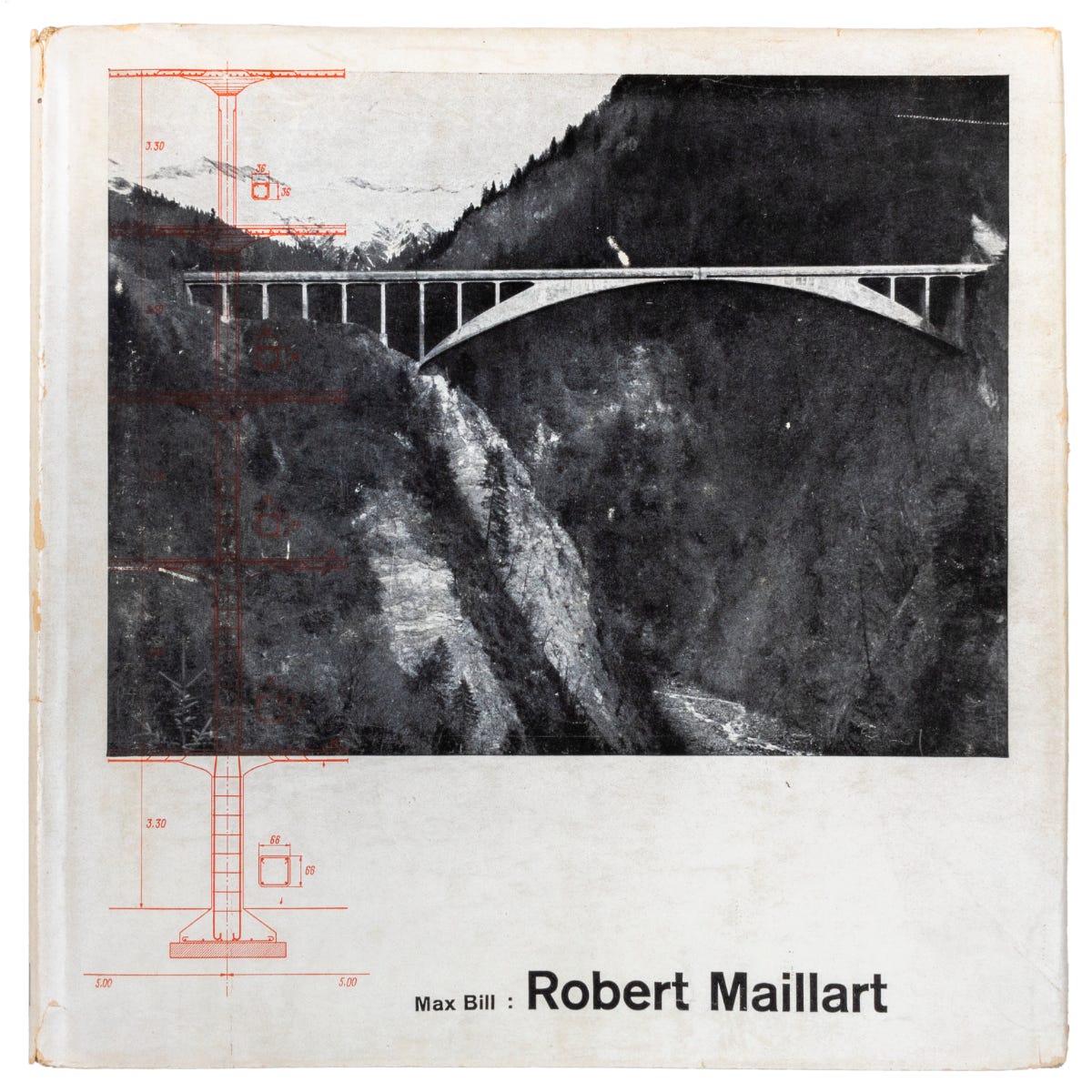

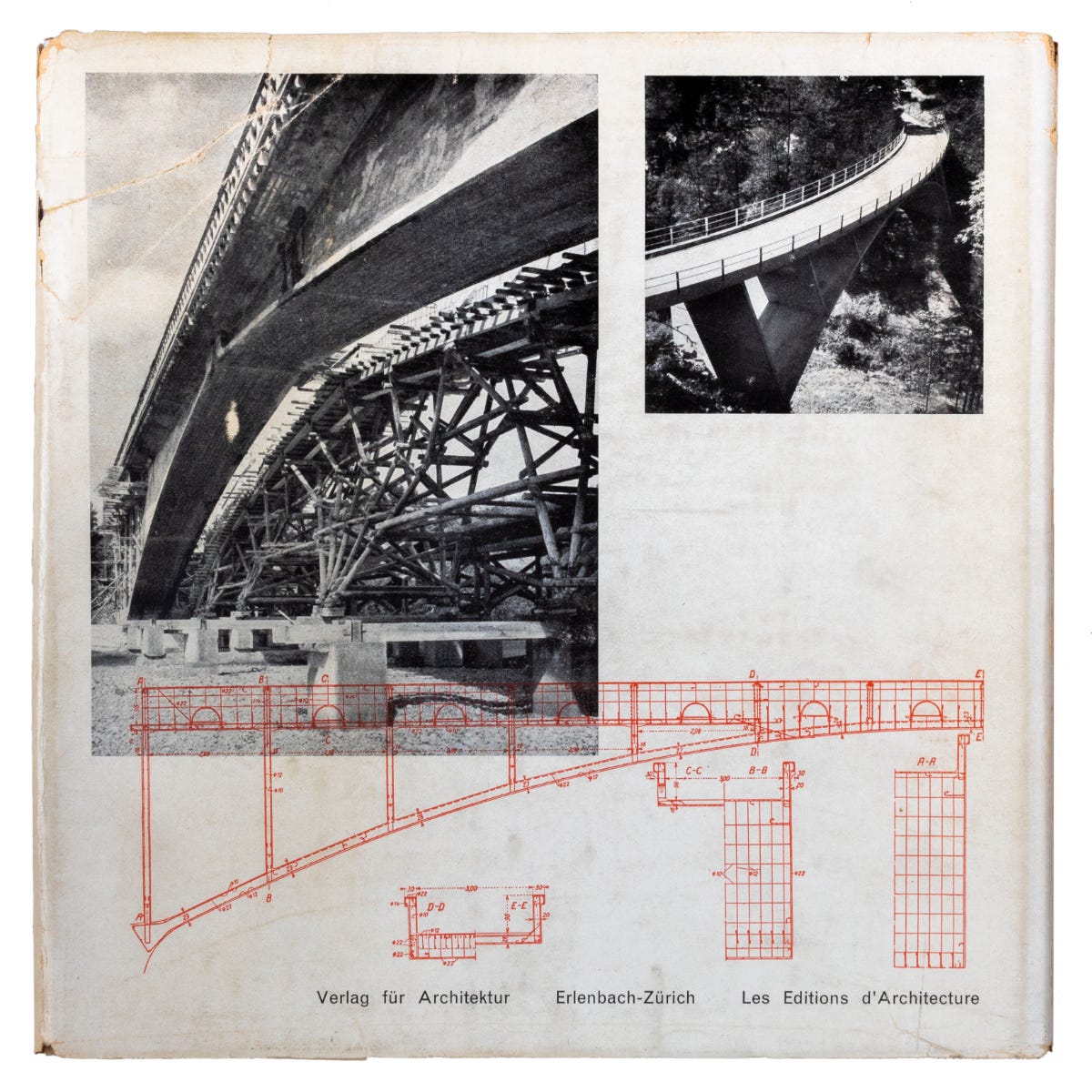

One of the eight archival texts reproduced in Félix Candela from Mexico City to Chicago is Candela’s own “New Architecture,” in The Maillart Papers: From the Second National Conference on Civil Engineering, from 1973. There, Candela admits “I realized that [Maillart] may have been one of the strongest influences at the critical moment in my career in which I was trying to become a builder of shells.” A seminal book on Maillart is Max Bill’s Robert Maillart, published by Verlag für Architektur, Erlenbach-Zürich in 1949. I included it in Buildings in Print: 100 Influential & Inspiring Illustrated Architecture Books, and here is what I wrote:

Multifaceted to say the least, Max Bill (1908–1994) was an architect, artist, graphic designer, industrial designer, even a politician. He trained at the Bauhaus from 1927 to 1929 but lived in his native Switzerland most of his life. In turn, he is considered one of the pioneers of the influential postwar Swiss Style of graphic design, aka International Typographic Style, defined by grid systems, sans serif typefaces, and a preference for photos over illustrations. Bill’s monograph on Swiss structural engineer Robert Maillart (1872–1940) is an exemplary example of that lasting style.

Maillart is one of the most famous designers and engineers of bridges, although he never produced any outside of Switzerland, and the ones he designed have shorter spans compared to those of his contemporaries, including fellow countryman Othmar Ammann, who designed the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge. But Maillart’s reinforced-concrete bridges were unprecedented: minimal in terms of materials, formally elegant, and wholly contemporary. The three-hinged arch bridges he devised to span rivers and valleys in the Swiss countryside were his most famous and influential creations.

Bill’s design of his eponymous, posthumous monograph on Maillart is aligned with the qualities of the engineer’s structures: clear, logical, and refined. Ten texts by Maillart and Bill (in German, French, and English) and documentation of dozens of bridges and buildings are printed on two types of paper that organize the contents into a consummate whole.

Back in 2014 I reviewed Chicagoisms: The City as Catalyst for Architectural Speculation, edited by Alexander Eisenschmidt with Jonathan Mekinda, and published by Park Books in 2013. I liked the book a lot, including it in my list of favorite books for 2014. Below is part of what I wrote in my review, edited for length.

Chicago is a city whose mythologies are more prevalent to foreigners than other cities [e.g., Al Capone and the mob, Oprah Winfrey and television, Frank Lloyd Wright and architecture] but this great book thankfully goes the opposite route, dismantling some of those myths and putting Chicago in an international context that shines a light on its influences. The dismantling of myths starts right away with the first essay (of eight), Penelope Dean's comparison of two contemporaneous exhibitions in 1976: 100 Years of Architecture in Chicago: Continuity of Structure and Form and Chicago Architects. The first, organized by SOM's Peter Pran and Mies biographer Franz Schulze, was representative of the myth (still strong) that painted Chicago architecture as starting with the Chicago School, moving through Mies, and then culminating (at the time) with corporate modern firms like SOM. The second, on the other hand, argued that such a simple view was misleading, ignorant of the variety in Chicago architecture that was portrayed in the show; Stanley Tigerman and Stuart Cohen, among others, were responsible for the oppositional exhibition. Dean's analysis examines the two exhibitions but also how people in places like New York reacted to the shows and how they viewed architecture in Chicago.

The following essays take further in-depth, scholarly looks at Alvin Boyarsky, the Museum of Modern Art's 1933 exhibition on Chicago, Ludwig Hilberseimer, Burnham's Plan of Chicago, and of course Mies van der Rohe, among other subjects. Each one ties Chicago to another Place (London, New York, Berlin, etc.) as a means of lending alternative viewpoints to the city as, among other things, a testbed for innovations in architecture and urban design. Aiding the essays are 20 short-form pieces (each one a two-page spread on a pink background) that focus on a particular project from an atypical perspective (buildings by Mies, Bertrand Goldberg, and SOM, as well as projects by the likes of Greg Lynn, Sean Lally, and others). All told, the book is one of the freshest recent books on architecture in Chicago, one that inspired the Art Institute exhibition of the same name, in which some voices from the book use the essays as frameworks for speculating on Chicago's future evolution.

Thank you for subscribing to A Weekly Dose of Architecture Books. If you have any comments or questions, or if you have your own book that you want to see in this newsletter, please respond to this email, or comment below if you’re reading this online. All content is freely available, but paid subscriptions that enable this newsletter to continue are welcome — thank you!

— John Hill

Ha! I’m halfway through this book now. Fascinating engineering and experimentation this man did. Now engineers rely completely on mathematics and unfortunately & sadly, liability.

I’m usually not into fiction, but novels “that are elevated through devious architecture at the heart of each story” are definitely works that I must look into. I feel also very curious now about Félix Candela’s work, which I was not familiar with at all. Thank you, sir!