This newsletter for the week of March 31 looks at the latest issue of the biannual Harvard Design Magazine (HDM), which examines the state of architectural practice today, pulls some practice- and Harvard GSD-related publications from the archive, and includes the usual headlines and new releases. Happy reading!

Book of the Week:

Harvard Design Magazine No. 52: Instruments of Service, guest edited by Elizabeth Bowie Christoforetti and Jacob Reidel (Buy from Harvard GSD)

Founded in 1997, the now biannual Harvard Design Magazine succeeded The Harvard Architecture Review, the student-run journal that was first published in 1980. In its name, Harvard Design Magazine (HDM) better reflects the makeup of the Harvard University Graduate School of Design, or Harvard GSD, which is comprised of three main departments: architecture, landscape architecture, and urban planning and design. Over its more than 25 years, HDM has gone through numerous iterations, marked by changes in size, design, and content. It started with a tabloid size akin to Metropolis and Interview magazines, then downsized to a smaller page size sometime in its teens, before adopting an almost business-like appearance in its early thirties. With issue 38, “Do You Read Me?,” in 2014, HDM was reconceived and relaunched with a new editorial and design approach under editor Jennifer Sigler, who helmed it until just before the pandemic hit in 2020. Since HDM returned in 2021, each issue has featured guest editors defining a theme and soliciting contributions from within and beyond the GSD. If readers of older issues picked up No. 52: Instruments of Service, guest edited by Elizabeth Bowie Christoforetti and Jacob Reidel, they wouldn’t recognize the current iteration of the magazine, considering it no longer features book reviews, faculty news, school news, and other content that once accompanied the scholarly essays that have been a mainstay of the publication. Nevertheless, I’m guessing they’d still be impressed.

In their editorial statement, Christoforetti and Reidel explain that Instruments of Service “examines the state of architectural practice today,” starting the issue “with one simple prompt: what do architects actually make and how is this changing?” Logically, the contributors are aligned with the theme, including the first essay, “Who Is the Architect?,” by George B. Johnston, who wrote Assembling the Architect: The History and Theory of Professional Practice (2020) and Drafting Culture: A Social History of Architectural Graphics Standards (2008). In answering the question posed by the title of the essay, Johnston admits that, “as both symbol and personification, ‘architect’ is a metaphor for the agents of vision and know-how” well outside of architecture (just think of how Russell Vought, as one example among many, is referred to as the architect of Project 2025), but ultimately what architects are and do is not fixed; it is influenced by “sociopolitical and technological transformations” amid “changing times and cultural constraints.”

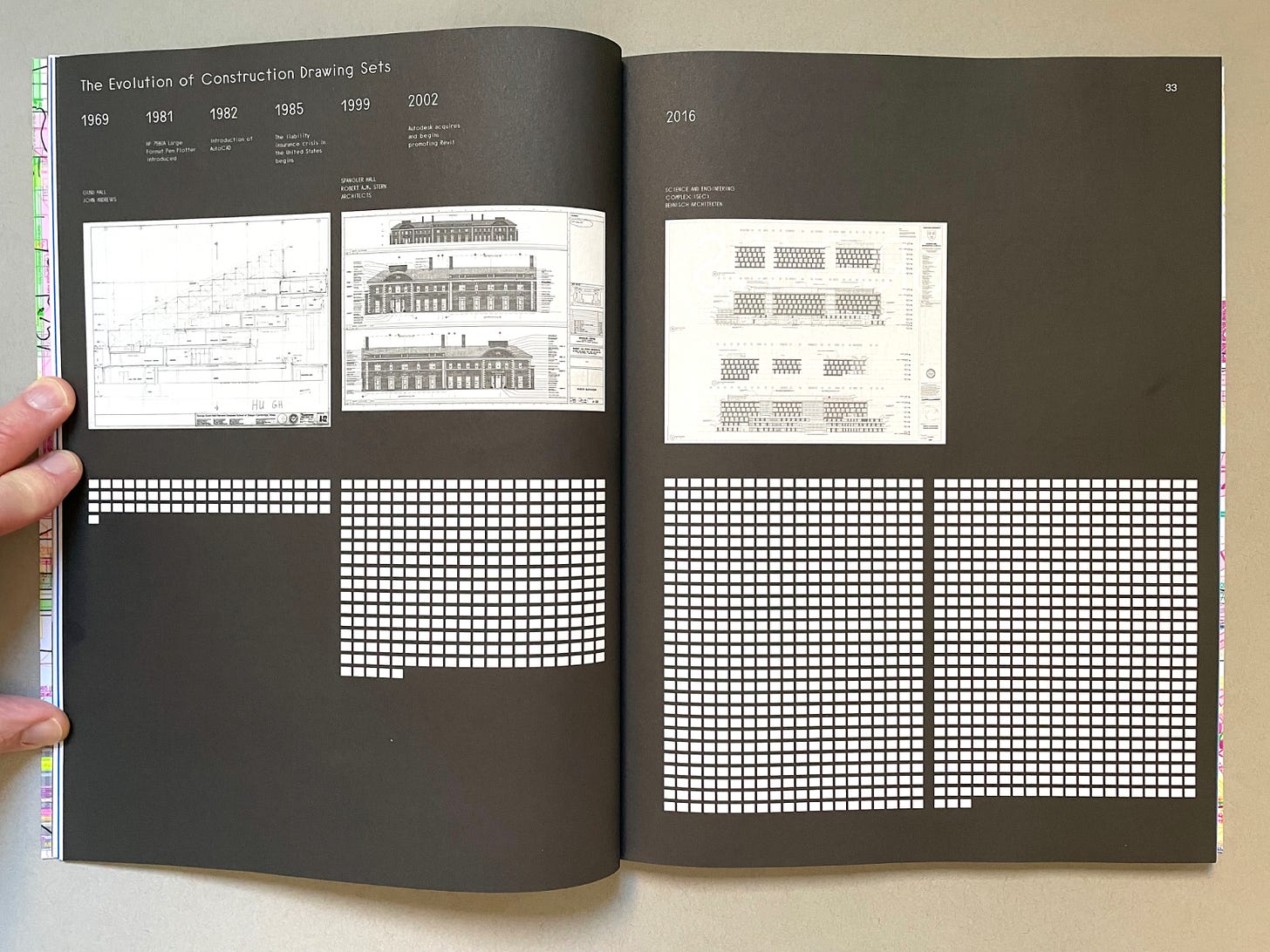

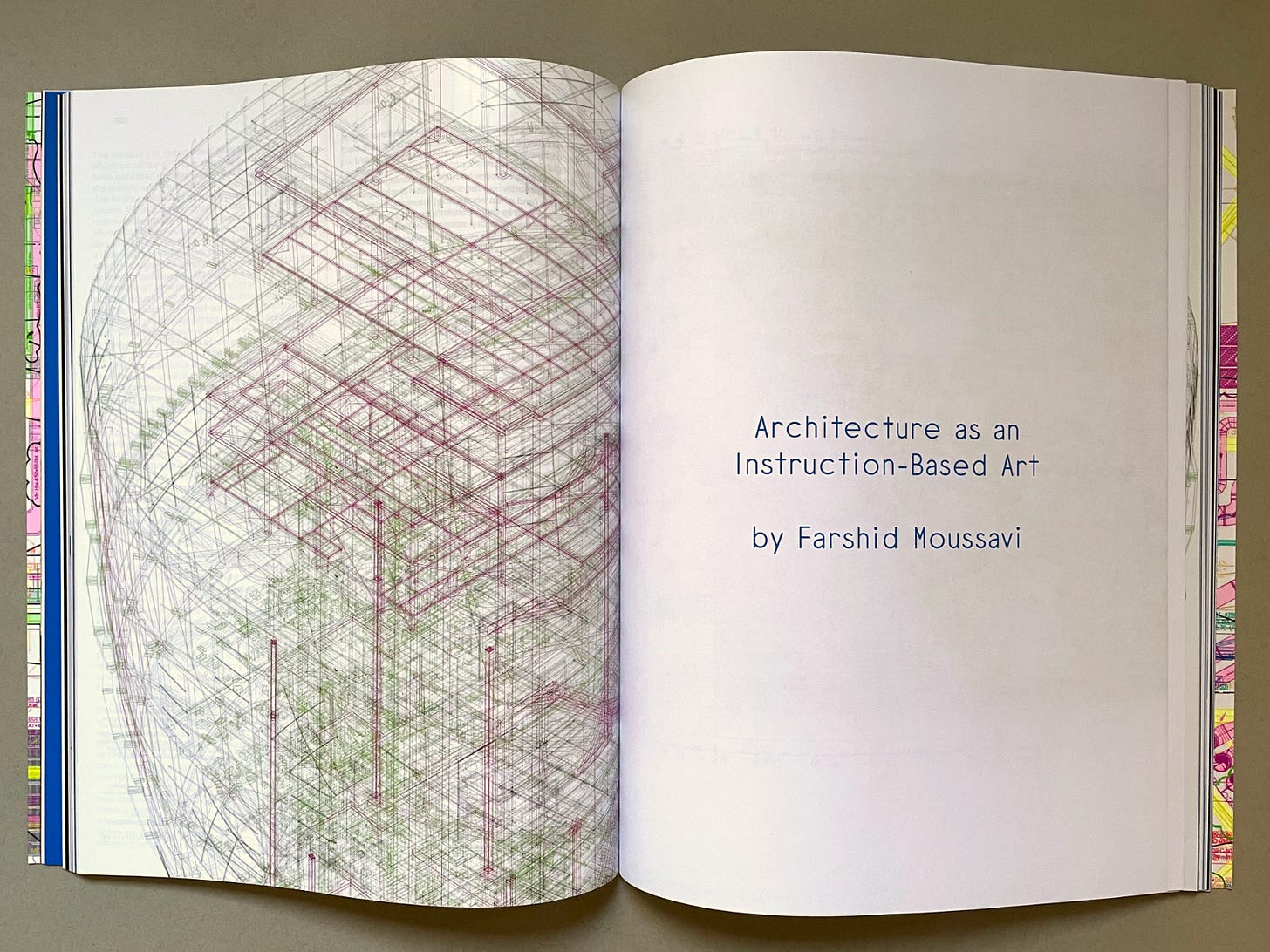

Changes in what architects do—in the drawings and other documents they produce—is visually depicted in a few places, including two examples shown here. The three spreads in “Documenting Complexity: The Evolution of Contract Documents and Construction Drawing Sets” by the guest editors clearly illustrate the growing complexity of architectural production over centuries: A building in 1812 could be built from just a dozen sheets, but this century a comparably sized building requires over one thousand sheets. That may change in the future, though, as witnessed by the colorful drawings in gatefolds accompanying Farshid Moussavi’s “Architecture as an Instruction-Based Art,” drawn from last year’s exhibition of the same name at the GSD. The drawings, which include the one on the cover, are the results of BIM models, not the traditional drawings made with a T-square and triangle or even AutoCAD. If most architects now work in 3D models in Revit, collaborating directly with engineers and other consultants, why even generate working drawings? Why not just share the model directly with the contractor, their subcontractors, and the fabricators and manufacturers?

Just as George B. Johnston was a logical choice for inclusion in Instruments of Service, so are a few other authors I had previously read: Matthew Soules, author of Icebergs, Zombies, and the Ultra Thin: Architecture and Capitalism in the Twenty-First Century (2021), contributes “Architecture Becoming Finance: A Means to Ethical Real Estate”; Albena Yaneva, author of Made by the Office for Metropolitan Architecture: An Ethnography of Design (2009), contributes “The Adventure of Making: A Pragmatist Perspective on Design”; and Reinier de Graaf, author of architect, verb. The New Language of Building, contributes “Crisis? What Crisis?: Exposure Therapy and the Future of Architectural Practice.” Kudos to the editors for packing the issue with these and other on-topic contributions, as well as for the numerous interviews and roundtables that fill out the remainder of the thick, 220-page issue—too much for me to read in its entirety. It’s clearly a timely issue, given the dramatic changes in technology underway; architects a quarter century from now may hardly resemble architects today, just like this issue of HDM is a far cry from its first issue.

Books Released This Week:

(In the United States, a curated list)

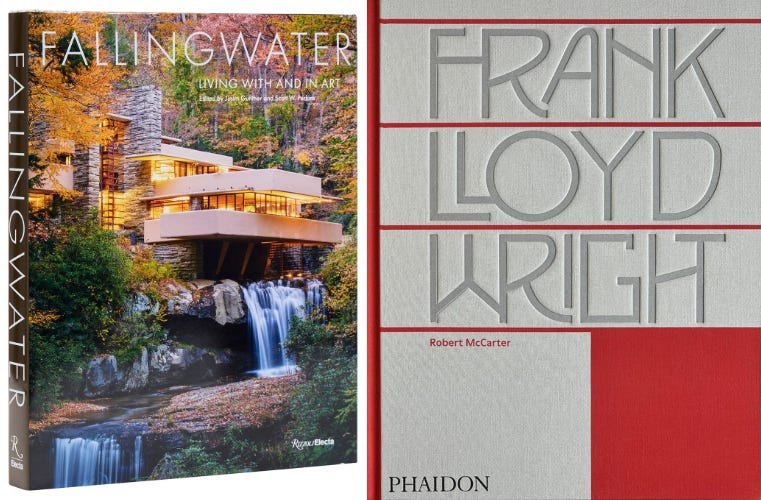

Fallingwater: Living With and In Art, edited by Justin Gunther and Scott W. Perkins (Buy from Rizzoli / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “An international treasure on the UNESCO World Heritage List, Fallingwater is a total work of art. This book, an exciting new look at a masterpiece, is a revelation for the first time seen here in its fullness.”

Frank Lloyd Wright, by Robert McCarter (Buy from Phaidon / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Now in a fully revised and updated new edition, this definitive account of the life and work of the modern master features an extensive selection of archival drawings, specially commissioned photographs, redrawn plans, and detailed drawings, as well as a complete list of Wright’s buildings and projects compiled by the Frank Lloyd Wright Archives.”

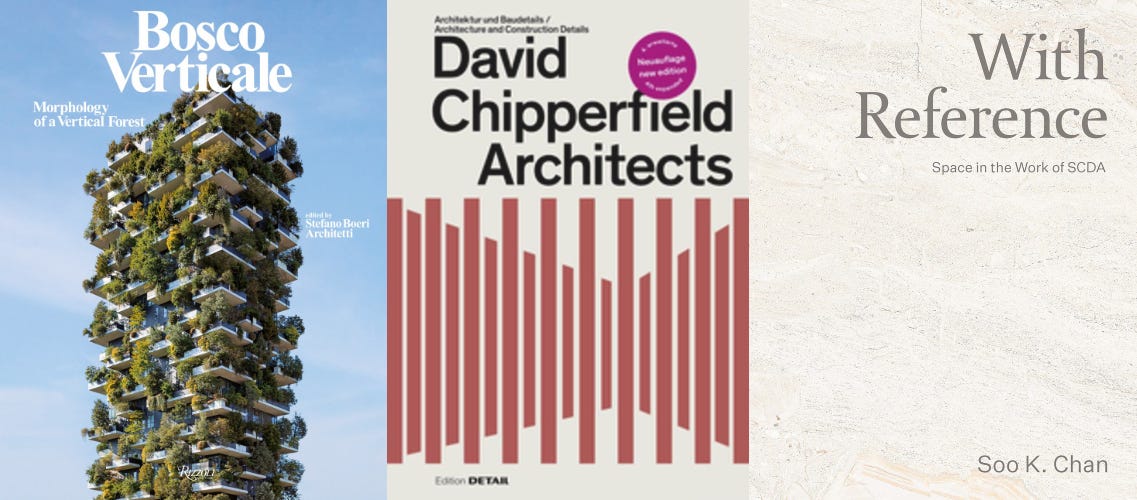

Bosco Verticale: Morphology of a Vertical Forest, edited by Stefano Boeri Architetti (Buy from Rizzoli / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “To commemorate the 10th anniversary of the Bosco Verticale, this book traces the history of a building that has become a symbol of Milan.”

David Chipperfield Architects: Architecture and Construction Details, edited by Sandra Hofmeister (Buy from Birkhäuser/Edition Detail / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “The monograph documents the sophisticated solutions of 25 international projects, including new buildings, renovations and interiors realized by David Chipperfield Architects.” (Bilingual German/English edition)

With Reference: Space in the Work of SCDA, by Soo K. Chan (Buy from ORO Editions / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Through SCDA's diverse array of projects, spanning mixed-use high-rises, hospitality venues, commercial and institutional developments, and residential masterpieces, the monograph showcases Soo K. Chan's mastery of shaping unique spatial experiences that transcend conventional boundaries.”

The Art of Connecting: Reuse of the Huber Pavilions, by Catherine Wolf (Buy from Birkhäuser/Edition Detail / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “This in-depth exploration of circular construction principles illustrates the reuse of materials from the Huber Pavilions at Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Zurich.” (Bilingual German/English edition)

Mäusebunker and Hygieneinstitut: Two Berlin Brutalist Icons, edited by Ludwig Heimbach (Buy from Jovis / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “This volume explores the different architectural principles underlying these closely situated [icons of brutalism], unpacking the intense debate concerning their preservation and questions surrounding their potential reuse, as well as appraising their economic and cultural value to the borough of Steglitz, Berlin.”

Why Do Architects Wear Black?, edited by Cordula Rau (Buy from Birkhäuser / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — A followup to the 2008 book of the same name that reveals architects’ answers to the question apparently every non-architect wants to know.

Full disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, AbeBooks Affiliate, and Bookshop.org Affiliate, I earn commissions from qualifying purchases made via any relevant links above and below.

Book News:

The New York Times reports (gift link) that Pilar Viladas, “an editor at Progressive Architecture, HG and The New York Times Magazine” and “the author of and a contributor to many design and architecture books,” died on March 15 at the age of 70.

Apollo magazine interviews Owen Hatherley about his latest book, The Alienation Effect: How Central European Émigrés Transformed the British Twentieth Century, published in the UK by Allen Lane, an imprint of Penguin.

The Astoria Public Library (the Astoria in Oregon, not my Queens neighborhood) is halfway through Hennebery Eddy Architects’ renovation of its 1967 brutalist building designed by “trailblazing architect” Ebba Wicks Brown, as detailed in this in-depth article in Oregon Artswatch.

For those in and around New York City, the 65th New York International Antiquarian Book Fair will take place April 3–6 at Park Avenue Armory, and across the street the Manhattan Rare Book & Fine Press Fair will be held on April 5. Click those links for more information and to get tickets.

From the Archives:

This week’s Book of the Week made me think of some old publications that happen to be organized into triptychs: one group that is focused on practice and happened to involve Jacob Reidel, co-editor of HDM 52, and three older HDM issues exploring one theme across three disciplines.

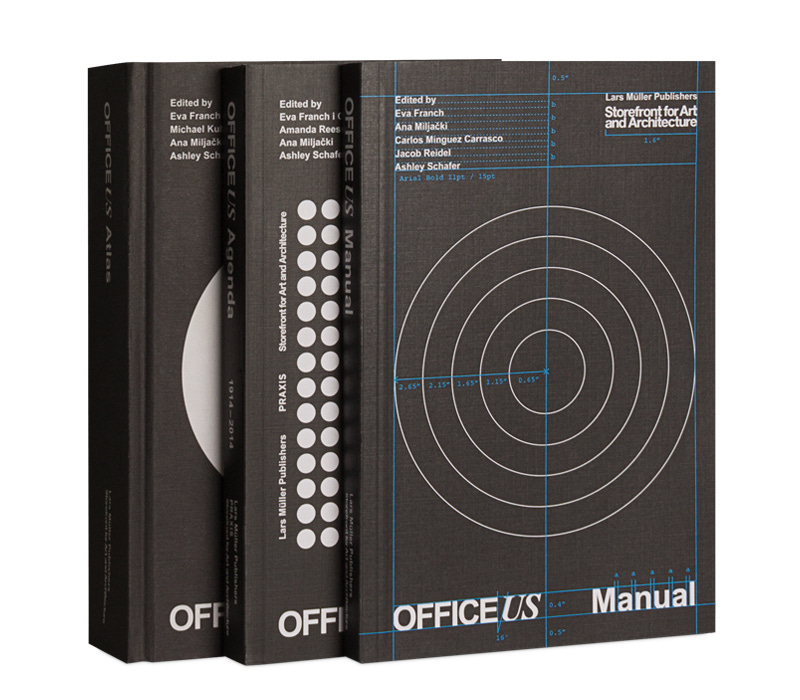

The United States Pavilion at Rem Koolhaas’s 2014 Venice Architecture Biennale was OfficeUS, curated by Eva Franch i Gilabert, Ana Miljački, and Ashley Schafer. The exhibition looked at one hundred years of American architects working overseas, and it resulted in three publications, all published by Lars Müller Publishers: OfficeUS Agenda, OfficeUS Atlas, and OfficeUS Manual. Agenda was published first, followed by Atlas and then Manual. I reviewed the second and third books on my blog, calling the 1,250-page Atlas “a gargantuan book on par with the exhibition itself” and describing the slimmer Manual as “much more fun—at least for architects,” given how it “delves into the inner-workings of some of these firms through that often overlooked document, the employee handbook.” (Here is a link to all three titles at Amazon.)

In 2012 and 2013, starting with issue 35, Harvard Design Magazine explored the GSD’s three departments by looking inwards to the “cores” of architecture, landscape architecture, and urbanism rather than outwards to their relationships with other fields. I looked at 35: Architecture’s Core? and 36: Landscape Architecture’s Core? on my blog in 2013, writing how I liked the scholarly contributions by Preston Scott Cohen, Reinhold Martin, and Farshid Moussavi in the former, while I appreciated the latter’s “balance of academia and practice.” The completist in me didn’t obtain 37: Urbanism’s Core? until a year ago, so now I see the trio of issues historically—as a snapshot of the disciplines and their concerns a decade ago, as well as of the GSD and HDM.

Thank you for subscribing to A Weekly Dose of Architecture Books. If you have any comments or questions, or if you have your own book that you want to see in this newsletter, please respond to this email, or comment below if you’re reading this online. All content is freely available, but paid subscriptions that enable this newsletter to continue are welcome — thank you!

— John Hill