This newsletter for the week of May 6 looks at Carlos Moreno’s The 15-Minute City: A Solution to Saving Our Time and Our Planet, released this week by Wiley, and catches up on new releases and headlines after spring break last week.

Book of the Week:

The 15-Minute City: A Solution to Saving Our Time and Our Planet by Carlos Moreno, with a foreword by Jan Gehl and afterword by Martha Thorne, published by Wiley (Buy from Amazon / Bookshop)

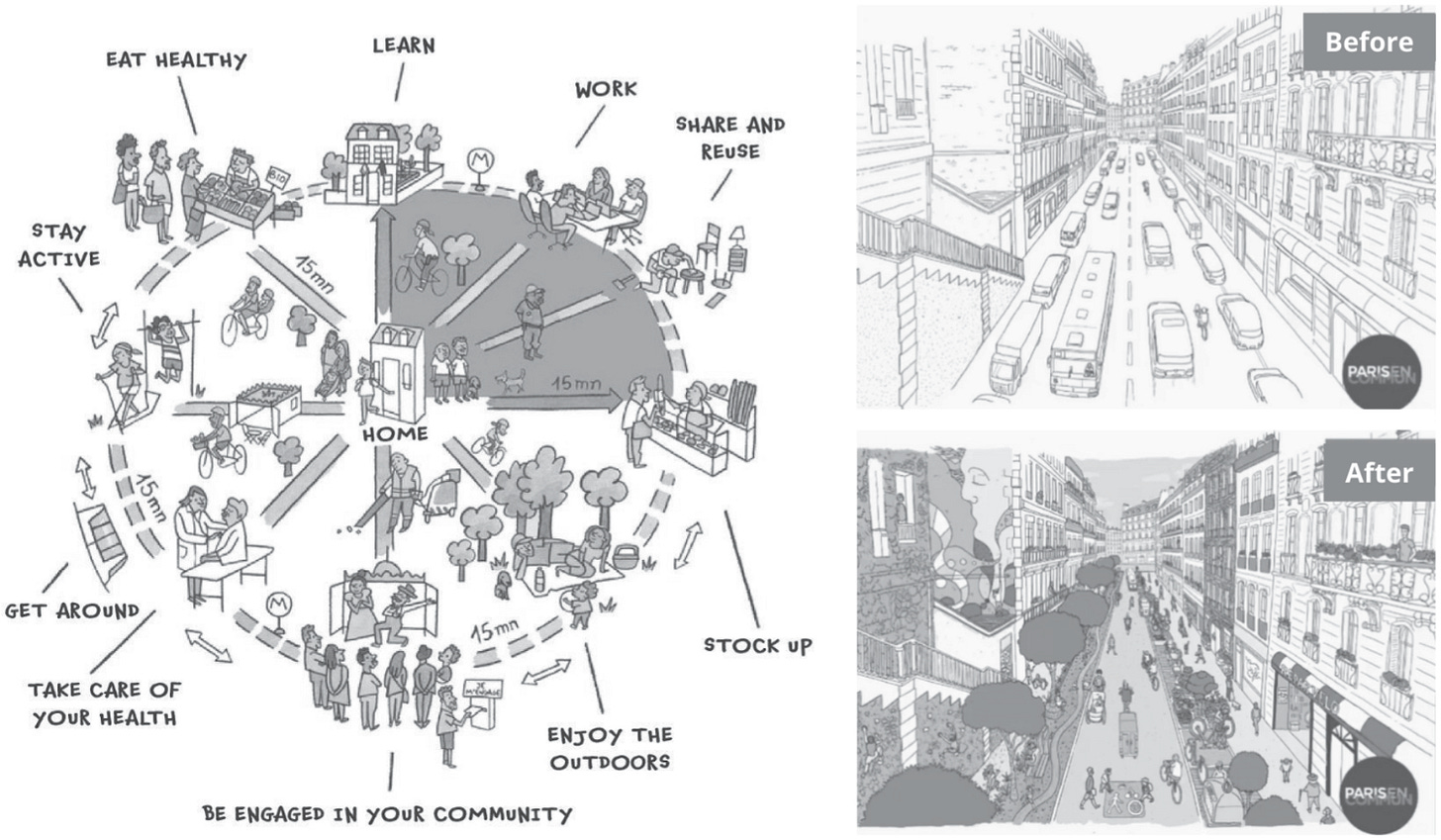

One adverse side effect of our digital age is the easy spread of conspiracy theories and the related politicization of nearly every aspect of life. Even something as commendable as the “15-minute city,” an urban design concept that aims for all residents being able to access their daily needs (housing, work, food, health, education, culture, leisure) within the distance of a 15-minute walk or bike ride, has been a target of conspiracy theories. In 2022, after the county government of Oxfordshire approved a system of “traffic filters” that will take effect later this year, and the Oxford City Council endorsed the 15-minute city model as part of its Local Plan 2040, both governments came under fire from online conspiracies targeting these efforts as “the latest nefarious plot to curtail individual freedoms.” A joint statement from the city and county in late 2022 addressed the misinformation and clarified the traffic filters and the 15-minute neighborhoods, saying the latter “aim to support and add services, not restrict them” and “this deliberate misrepresentation of data is harmful to the public debate.”

For me, someone educated in urban design, it is hard to see the 15-minute city as a nefarious plot to curtail individual freedoms, given that it promotes equitable access to services and reduces the need to drive for them, and that in theory it harkens to eras before the rise of the automobile and the catering of cityscapes to cars, thereby making it more appealing to conservatives. But misinformation arises from misunderstanding and misrepresentation, among other things, and one way to reduce the spread of misinformation is to clarify a position by putting it in writing, making the ideas behind it readily available. Such can be seen with the release this week of The 15-Minute City: A Solution to Saving Our Time and Our Planet by Carlos Moreno, the Paris-based scientist and professor who started to develop the 15-minute city concept about 15 years ago, and who clearly explains the concept to a general audience across the book’s 276 pages.

Timing is everything, they say, and conspiracy theories targeting the 15-minute city followed from two contemporaneous events: the Covid-19 lockdowns in March 2020 and the embrace of the model by incumbent mayoral candidate Anne Hidalgo in Paris the same month. While the second round of the two-round election was postponed until June, with lockdowns eerily transforming the streets of Paris and every other city in the world over the ensuing months, Hidalgo stuck with the concept as a pillar of her second term and won reelection. Although Hidalgo had incorporated elements of the 15-Minute City during her first term, especially in the widespread, applauded insertions of bike lanes that made that mode of transportation easier and safer, and the 15-Minute City had already gained recognition, as in the 2019 Obel Award, it took the one-two punch of the pandemic and Paris election to push the concept into the spotlight, increase its spread to other cities, such as Oxford, but also make it ripe for conspiracy theories.

Paris is the subject of two chapters in Moreno’s book, coming after nine chapters that lay down the foundation for the 15-minute city and ahead of another nine chapters on other cities implementing the concept. Paris, in turn, makes up the heart of the book and therefore can be seen as the most important case study for Moreno, if anything because Hidalgo turned the 15-minute city into public policy. “Our aim is to propose a different way if life,” Moreno writes in the second of the two Paris chapters, “based on polycentric proximity and changes in habit that alter the way we around.” Alter how? Moving “from forced mobility to chosen mobility […] on foot or by bike.” As the book's subtitle clearly spells out, such an approach saves people time — the time they would spend in traffic or on public transit due to long commutes — but also attempts to make a contribution to sustainable development and the fight to limit climate change.

Readers encounter Paris early in Moreno’s book, not long after Jan Gehl’s foreword (see also the bottom of this newsletter), in an early chapter, “Journey Through a Fragmented City,” explaining why the 15-minute city is even necessary today. Paris was the target of Le Corbusier’s Plan Voisin, which “proposed the destruction of the medieval and Haussmannian districts of Paris to create a new modern aesthetic based on high-rise buildings.” Although Moreno singles out Le Corbusier and the Athens Charter he wrote in 1933, as well as Robert Moses in New York, he does not limit the causes of urban ills to Corbu, unlike others (I’m looking at you, Thomas Heatherwick!). Instead, he puts the blame where it belongs — cars — while also discussing the “geography in urban time” and aspects of urban change that led to the “proximity revolution” he espouses in the 15-minute city. In these early chapters, the book effectively gives readers the reasons for his development of the 15-minute city, which he then outlines in fairly broad terms before presenting it in more detail in the Paris chapters and the other city chapters in the last half of the book.

But, you might be asking, wasn’t Paris already a “15-minute city”? Shouldn’t the model’s target be more car-dependent places outside of cities, such as suburbs without mixed-use zoning, rather than cities that didn’t tear down its old districts for high-rise buildings? One answer is that in Paris, New York, and other cities that are arguably 15-minute, the ability to have food, education, recreation and other needs within a 15-minute walk or bike ride is not equitably distributed. So, in the case of the model being applied to Paris, the Portes de Paris pilot project in 2017 focused on the working class neighborhoods of Seine-Saint-Denis northwest of Paris, which will be the epicenter of the 2024 Olympics but is also “one of the most deprived areas of France,” per Moreno. So, when the Olympic Games are broadcasted in late July and early August, Paris will be displaying to the world how a “more sustainable Games” can be achieved and how it is applying the 15-minute city concept to improve the daily lives of Parisians.

Books Released This Week:

(In the United States, a curated list)

Released last week:

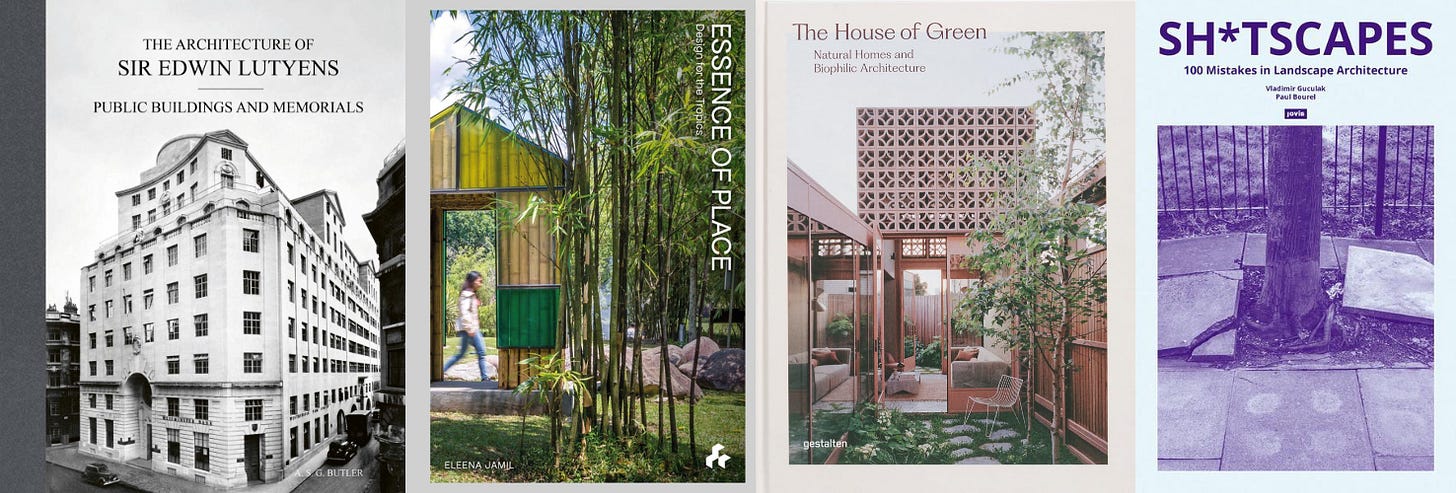

The Architecture of Sir Edwin Lutyens: Public Buildings and Memorials by A. S. G. Butler, with George Stewart and Christopher Hussey, published by ACC Art Books (Buy from Amazon / Bookshop) — The third and last volume in ACC’s reprint of the classic “Lutyens Memorial” — I reviewed the first, Country Houses, last year.

Essence of Place: Design for the Tropics by Eleena Jamil, published by Artifice Press (Buy from Amazon / Bookshop) — The first monograph on Malaysian architect Eleena Jamil, whose eponymous practice is motivated by “the importance of place and the vernacular local architecture of Malaysia.”

The House of Green, published by gestalten (Buy from Amazon / Bookshop) — The latest survey of contemporary architecture from gestalten focuses on “architecture and interiors incorporating nature into their designs,” from houses to skyscrapers.

Sh*tscapes: 100 Mistakes in Landscape Architecture by Vladimir Guculak and Paul Bourel, published by JOVIS (Buy from Amazon / Bookshop) — To counter the prevalence of idealized visualizations, this book presents “a hundred failures made in the design, construction, or maintenance processes of urban landscapes.” Finally, I know a term for things like this that I’ve found in my neighborhood: shitscapes!

Released this week:

Albert Frey: Inventive Modernist edited by Brad Dunning, published by Radius Books (Buy from Amazon / Bookshop) — Released about a month after Frey and Kocher's Aluminaire House was put on permanent display in Palm Springs, this book “tracks the scope and significance of Frey’s career, from his early days in Paris working with Le Corbusier to his rise as the iconic architect of Palm Springs.”

Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts: Reimagining a Museum for the 21st Century by Jeanne Gang, Kate Orff and Dr. Victoria Ramirez, published by Scala Arts Publishers (Buy from Amazon / Bookshop) — A slim volume on the AMFA, which was transformed by Studio Gang a year ago.

Prior Art: Patents and the Nature of Invention in Architecture by Peter H. Christensen, published by The MIT Press (Buy from Amazon / Bookshop) — Well before Steve Jobs patented an Apple store on the Upper West Side, architects in the 19th century embraced patenting in significant numbers, as this “record of the marriage of intellectual property and architectural invention” explores.

Full disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, AbeBooks Affiliate, and Bookshop.org Affiliate, I earn commissions from qualifying purchases made via any relevant links above and below.

Book News:

(A hefty dose of UK publications this week)

Kenneth Frampton reviews Housing Atlas: Europe 20th Century, which was released in Week 8/2024, for Architecture Today, calling the “immense body of comparative research and documentation” a “magnum opus” and “such a tour de force as to render a review of limited length virtually impossible.”

Over at BD, Nicholas de Klerk reviews Charles Holland's How to Enjoy Architecture: A Guide for Everyone, which was released a couple of weeks ago, commending how “it is conversational and takes as much pleasure — a wholly underrated aspect of architecture — in the text itself, as it does in the things it discusses.”

Photographer Jamie McGregor Smith, who spent the five years capturing brutalist and modernist churches across Europe, presents a dozen of his favorites from his new Sacred Modernity book for Dezeen. (The book will be released in the US next week.)

Charles Saumarez Smith, author of the excellent The Art Museum in Modern Times, reviews Gavin Stamp’s posthumous book Interwar: British Architecture 1919–1939 for The Critic, writing that “it is extremely hard to pick any holes in the depth and range of Stamp’s knowledge.”

From the Archives:

Jan Gehl, the Danish urban designer who wrote the foreword to Carlos Moreno’s The 15-Minute City, has written numerous books documenting and espousing his sympathetic approach to pedestrianizing city centers. There are the classic Life Between Buildings, which was first published in 1971, and How to Study Public Life, the 2013 book that revealed his on-the-ground techniques of observation. Back in 2010 I reviewed Cities for People, his fifth major book, commending its clarity in spreading Gehl’s message through an abundance of photographs and statistics. Given the lethargy in implementing urban changes geared to pedestrians and cyclists, the book is as relevant, if not more so, today as when it came out a decade and a half ago.

Of the roughly dozen books in my library about Paris, the one that came to mind when reading the chapters in Carlo Moreno’s book about Paris was Nairn’s Paris, which was first released in 1968 and then reissued as a handsome hardcover by Notting Hill Editions on its 50th anniversary in 2018. (The publisher has done the same with Nairn’s Modern Buildings in London and Nairn’s Towns.) Although I’ve only dipped into parts of Nairn’s Paris here and there (hopefully I can use it properly in situ someday), the synergies between Moreno and Nairn are found in the way each prized the human and human-scaled, the “real” and the local. “About one third of the book is discovery,” Nairn wrote, “in the sense that I came upon the sites by accident or by following a topographical hunch” — that phrase and the one on the cover, about his love of drinking and places to drink, sum it up pretty well. In turn, Nairn recommended that people in 1968 “turn off the main road” to make similar accidental findings. Nowadays, I’m guessing, those findings would be made by taking a different bike path and seeing where it leads.

Thank you for subscribing to A Weekly Dose of Architecture Books. If you have any comments or questions, or if you have your own book that you want to see in this newsletter, please respond to this email, or comment below if you’re reading this online. All content is freely available, but paid subscriptions that enable this newsletter to continue are welcome — thank you!

— John Hill