This newsletter for the week of January 7 — the first newsletter of 2025 — looks at a new monograph on the residential architecture of SO–IL, the Brooklyn firm of Florian Idenburg and Jing Liu. A couple older books related to this “Book of the Week” are at the bottom of the newsletter: the first by Idenburg and LeeAnn Suen on offices, and the second a survey of multi-family housing in Zurich. A bunch of headlines, spilling over from the end of 2024, and a few new releases are in between. Happy reading!

Book of the Week:

In Depth: Urban Domesticities Today, edited by Florian Idenburg and Jing Liu, with photographs by Iwan Baan and Naho Kubota (Buy from Artbook/DAP [US distributor for Lars Müller Publishers] / from Amazon / from Bookshop)

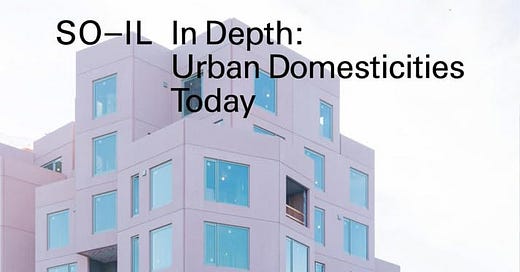

The bold pink building on the cover of SO–IL’s In Depth: Urban Domesticities Today is 144 Vanderbilt, a residential building under construction in Brooklyn’s Fort Greene neighborhood. SO–IL, the studio founded by Florian Idenburg and Jing Liu in Brooklyn in 2008, describes the project as “the third installment (after 450 Warren and 9 Chapel) in a series of residential buildings aimed at transforming the conventional multi-family housing typology in New York” — this from page 248 of the firm’s monograph/gentle manifesto on domestic architecture. It is a very bold assertion considering the entrenched, market-driven formula for multi-family residential architecture in New York City, but it is also a very confident one, enabled by them partnering up with Tankhouse, the development company founded by Sam Alison-Mayne and Sebastian Mendez, on all three projects.

One could further chalk up the daring nature of these three projects — with massings, facades, outdoor spaces, corridors, and unit plans that veer from the norm — to the fact Alison-Mayne is the son of Morphosis’s Thom Mayne and therefore has experimental architecture in his blood, though credit also has to go to Mendez, who worked as an architect at Foster+Partners before the duo founded Tankhouse in Brooklyn in 2013 (the two met while Alison-Mayne was working at Sciame, when the company was serving as contractor on Foster+Partner’s Sperone Westwater). Architects as developers are rare and therefore welcome, given that they naturally value architecture and are more likely to take chances with architectural ideas, be they formal, programmatic, tectonic, or even theoretical. I’m guessing the meeting of the SO–IL and Tankhouse principals was something of a kismet, given that they are all based in Brooklyn, which has seen a development frenzy this century, and that none of them appear willing to accept the city’s apartment-building status quo.

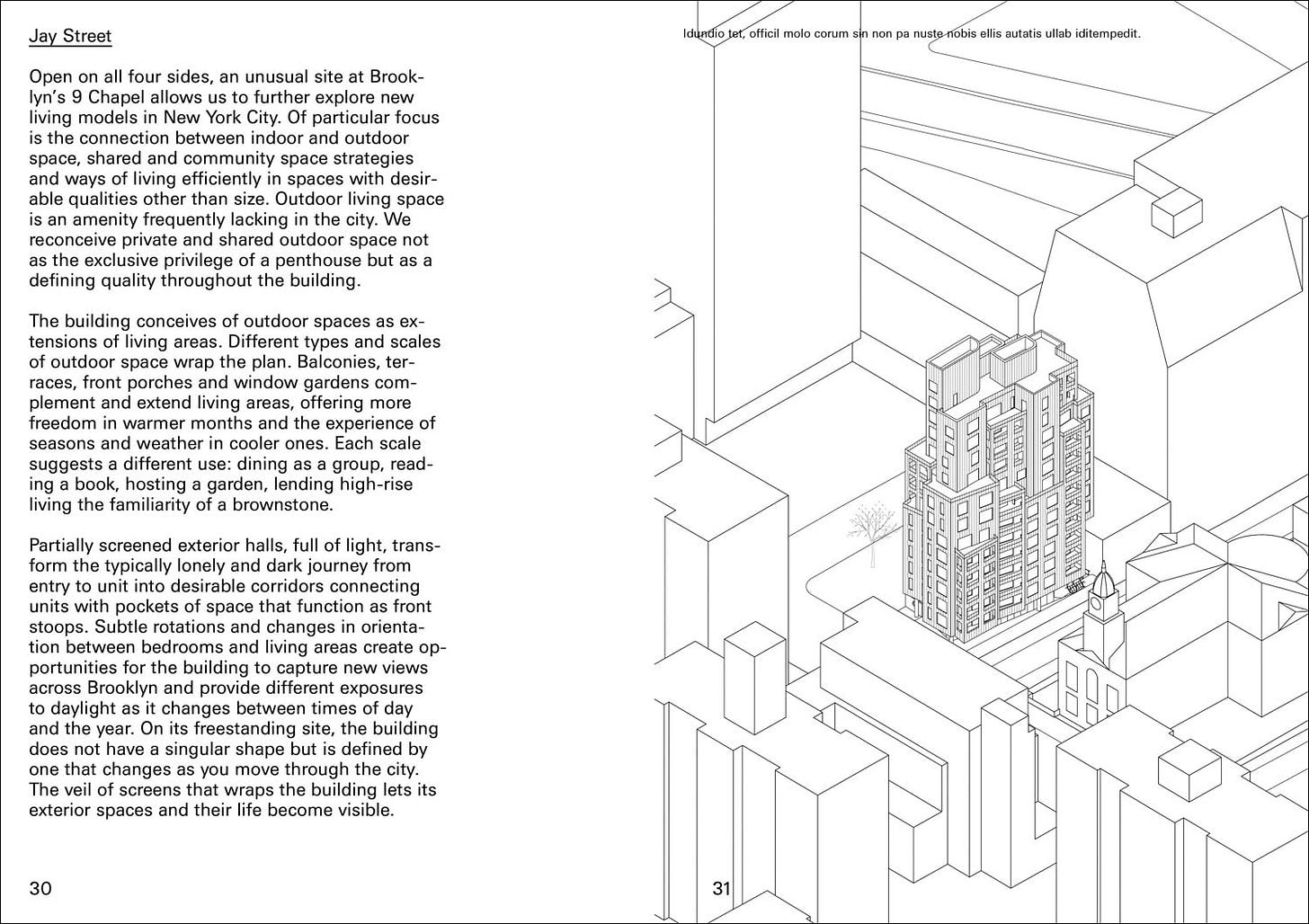

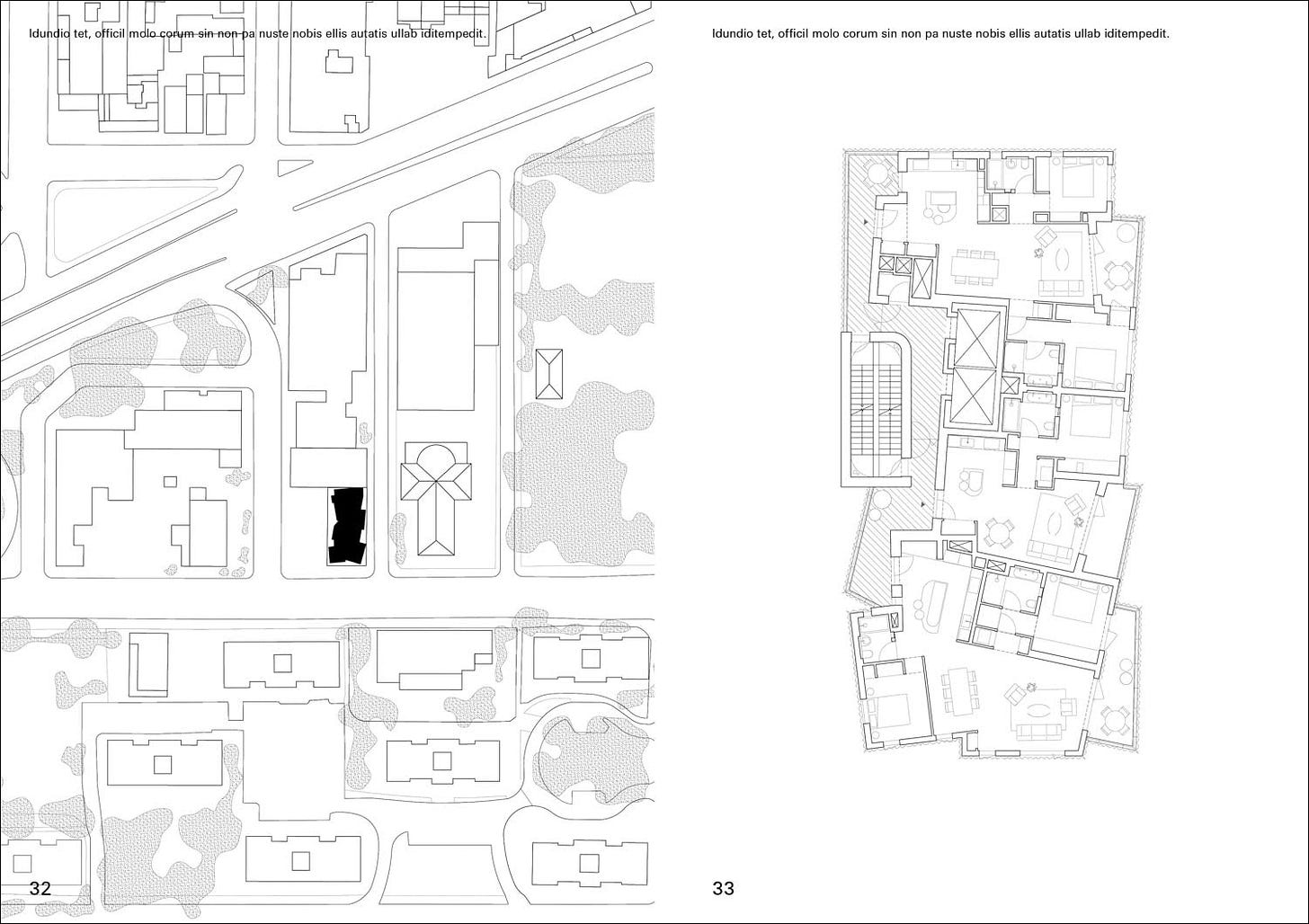

What is it that makes the trio of SO–IL/Tankhouse projects so unconventional, so appealing? The word I favor in describing them — having walked by 450 Warren after it was completed and occupied, and having recently gotten inside the projects at 144 Vanderbilt and 9 Chapel under construction — is relaxed. For sure, the buildings are methodically worked out at every level, but to me the massings, circulation, and unit plans are more relaxed than rigid, more asymmetrical than composed, and more informal than ordered. The relaxed massings can be grasped in the cover photograph of 144 Vanderbilt, where the pink-precast volumes ascend to a craggy corner peak, unlike any other apartment building in the city; relaxed circulation is apparent in the mesh-lined courtyard and open-air corridors of 450 Warren; and relaxed unit plans come across in the floor plan of 9 Chapel in the below spread, where living/dining spaces are more flowing than open, defined by angled walls and L-shaped spaces.

The trio of buildings are clear departures from the recent norm in New York City residential architecture, which tends to be either extruded volumes with glass skins or EIFS facades draped with shallow, barely usable balconies. The SO–IL/Tankhouse condos in Brooklyn, on the other hand, feature sculpted, asymmetrical exteriors; custom precast panels, concrete blocks, and/or metal skins; large windows; and generous terraces. These qualities are the synthesis of SO–IL’s design thinking and decision-making at multiple levels, from their novel treatment of the NYC Zoning Code, which dictates use, bulk, and height but far too often wags the architectural dog, to the abolishment of interior, double-loaded corridors, and the time-consuming development of custom materials for the facades.

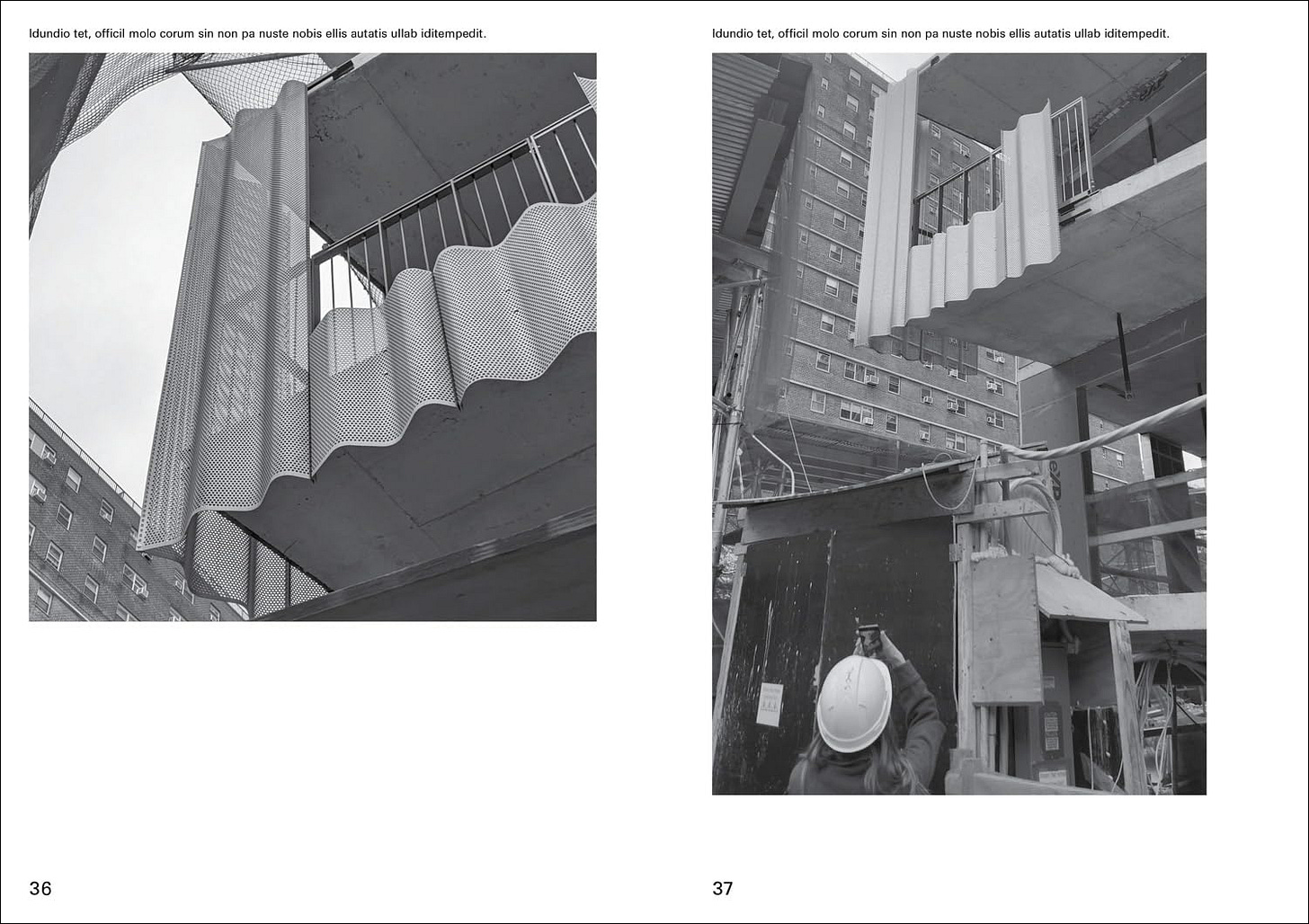

Fittingly, these three areas — zoning, corridors, and facades — are the subject of the three essays included in In Depth: Urban Domesticities Today, released in the US this week by Lars Müller Publishers. In “Codes of Living” Ted Baab, who worked at SO–IL for eleven years but now helms BAAB, gives a historical overview of New York City’s zoning code and explains how SO–IL interpreted it and energy codes in their multifamily designs. Nicolas Kemper, publisher of New York Review of Architecture, briefly looks at corridors in architectural history, medical studies, and the SO–IL/Tankhouse’s buildings in “Cancel the Corridor.” Finally, SO–IL’s Karilyn Johanesen, in “Layered Lives,” explains how the practice approaches the design of building facades in response to zoning and energy codes, and describes the design of 9 Chapel’s perforated skin (below) in particular.

These three essays comprise only about 40 pages (pp. 81–120) of the 360-page book — a book that is also unconventional, at least when compared to other architectural monographs. Instead of projects presented one after another, the book alternates stretches of text and b/w images with stretches of full-bleed color photographs. A lengthy introductory essay by Jing Liu begins the book, laying out her own thinking on the idea of home and the unique approach taken by SO–IL in residential architecture, be it single-family or multi-family; it’s a revealing essay with lengthy footnotes that are well worth reading. It is followed by Naho Kubato’s photographs of the Bergen Residence, the renovation of a Brooklyn townhouse. Then come the essays, which are followed by 50 pages of Iwan Baan’s photographs of 450 Warren. SO–IL’s twelve residential projects to-date are documented on pages 169 to 264, the largest chunk in the book, described in brief texts, drawings, and model photos. Iwan Baan’s photographs of Las Americas, a social housing project in Mexico, follow, as do his construction photographs of 144 Vanderbilt at the end of the book.

Hard to convey in still images, but impossible to ignore when holding the book, is the addition to some of the color photographs, especially 144 Vanderbilt, of a textured glossy layer at the windows. (The effect can be seen in this video posted to Instagram by architect and publisher; the book’s graphic designer, it should be noted, was Geoff Han.) This layering further distances SO–IL’s residential monograph from other monographs, while it also draws attention to the windows themselves: the surfaces that separate inside from outside but provide visual connections between these realms. The windows in the Tankhouse/SO–IL projects don’t come across as importantly as the asymmetrical massings, open-air corridors, and custom facades, but their highlighting in the glossy layer makes one aware of their size, larger than traditional hung windows, as well as the fact they are windows, not glass skins. Thinking of the windows via these photo-manipulations makes me realize that, even though the three residential projects in Brooklyn I’ve been discussing here are unconventional, they are rooted in place, cognizant of some traditional aspects of architecture in NYC and how people make their homes in the city.

Books Released This Week:

(In the United States, a curated list)

75 Architects for a Sustainable World by Agata Toromanoff (Buy from Random House/Prestel / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Filled with striking photography as well as design inspiration and hope for a better tomorrow, this beautifully designed volume profiles the work of a global selection of visionary architects who are reimagining our built world for the future.”

Archigram Ten by Peter Cook (Buy from ACC Art Books [US distributor for Circa Press] / from Amazon) — “After a 50-year pause for thought, Archigram is back. Edited by Peter Cook, with contributions from Archigram founding members Dennis Crompton, David Greene and Michael Webb, and with inputs from numerous contemporary designers, technologists and critics, Archigram 10 takes a wry backward glance and imagines a bold leap forward.”

Versailles from the Sky by Thomas Garnier (Buy from Thames & Hudson / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Versailles is particularly beautiful when seen from above, and the stunning images in this volume reveal the ingenious geometry of its different spaces, while also offering a panoramic view of the estate in all its immensity.”

Full disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, AbeBooks Affiliate, and Bookshop.org Affiliate, I earn commissions from qualifying purchases made via any relevant links above and below.

Book News:

Building Design compiles “this year’s must-read titles,” with links to reviews of books by Gavin Stamp, Carlos Moreno, Charles Holland, and others.

“From an atlas of never-built architecture to a monograph on Alexander Girard,” Fast Company contends, “2024 had a wealth of exciting design books.”

ASLA’s The Dirt rounds up what it considers the “10 best books of 2024.”

The editors of Metropolis have put together their “Ultimate Winter Reading List.”

The staff at Glasstire, “the oldest online-only art magazine in the country,” compiles their “Favorite Art Books of 2024,” though the inclusion of a few books from many, many years ago makes it veer from the usual year-end lists. Claire Bishop's Disordered Attention: How We Look at Art and Performance Today, which has one of its four essays devoted to Modernist architecture and design, is a standout.

“Words, spaces & discourses: a look at the best design and architecture books of 2024,” according to STIR World.

“10 Books Every Architect Should Read,” at Parametric Architecture.

From the Archives:

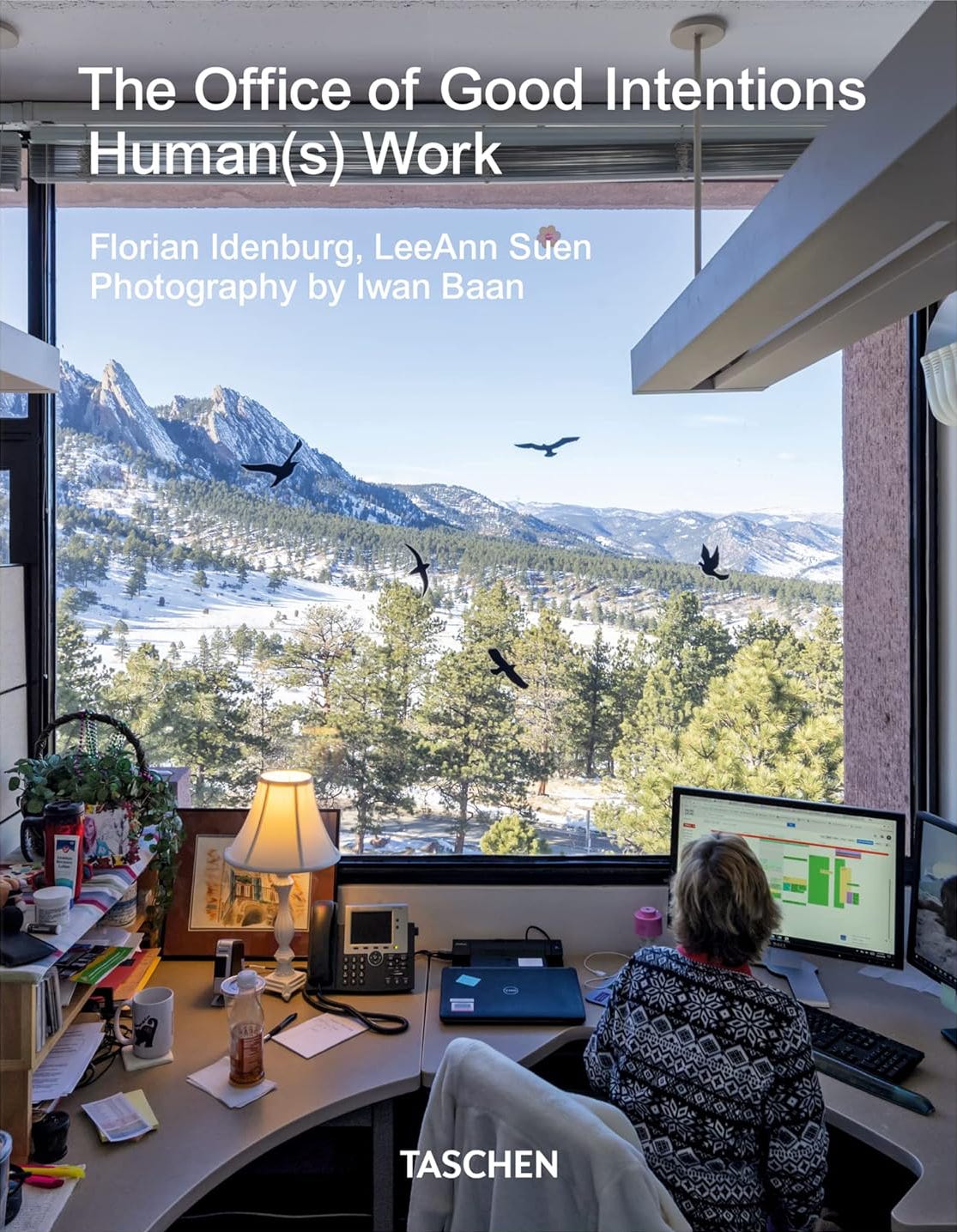

A few years before the release of In Depth: Urban Domesticities Today, SO–IL’s Florian Idenburg co-wrote, with LeeAnn Suen, a book on the architecture and design of office buildings and their interiors, furniture, and technologies. The Office of Good Intentions: Human(s) Work, published by Taschen in 2022, is similar to In Depth in the way it departs from publishing conventions. The various essays, archival images, photographs (by Iwan Baan, of course), and other contents are described by the authors as “an impressionistic collection,” one that is presented in a more or less random order, on various papers and page sizes, and with hole punches — all contributing to that assertion.

Although the office environments discussed and documented in the book reach back decades (the photo essay on Paul Rudolph’s now-demolished Burroughs Wellcome headquarters is a standout), the release of the book in 2022, when people had yet to return to offices full time during the tail end of the pandemic, makes it a timely look at the evolution of the American office over a half-century. Although the authors and their assistants (editor/writer Zoë Ritts, researcher Duncan Scovil, and graphic designer Sean Yendrys) don’t pretend to forecast the future of offices, their reverence for the typology is clear. Seen relative to In Depth, the book reveals SO–IL’s attention to various typologies and makes me wonder when a publication on museums and other arts institutions will see the light of day.

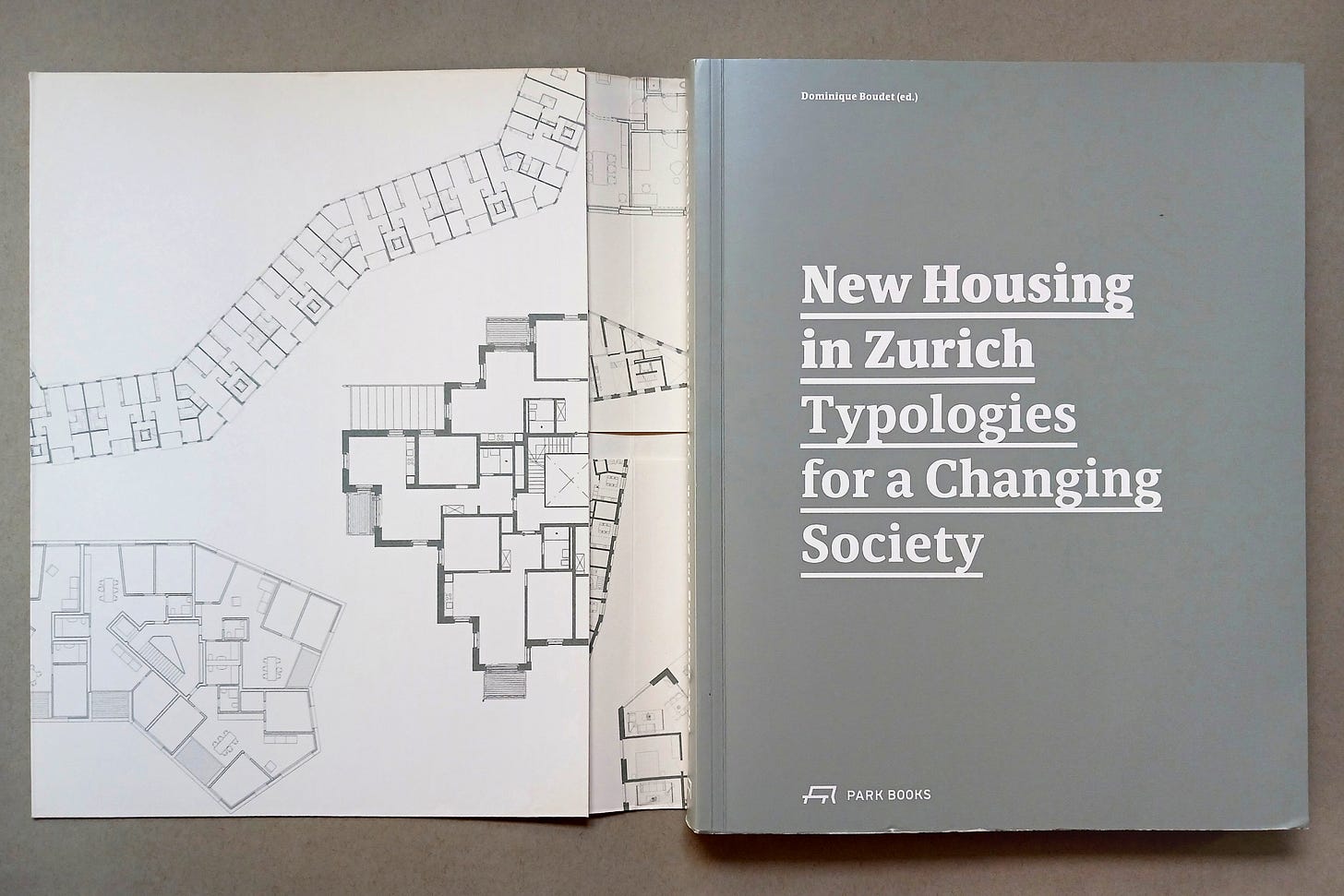

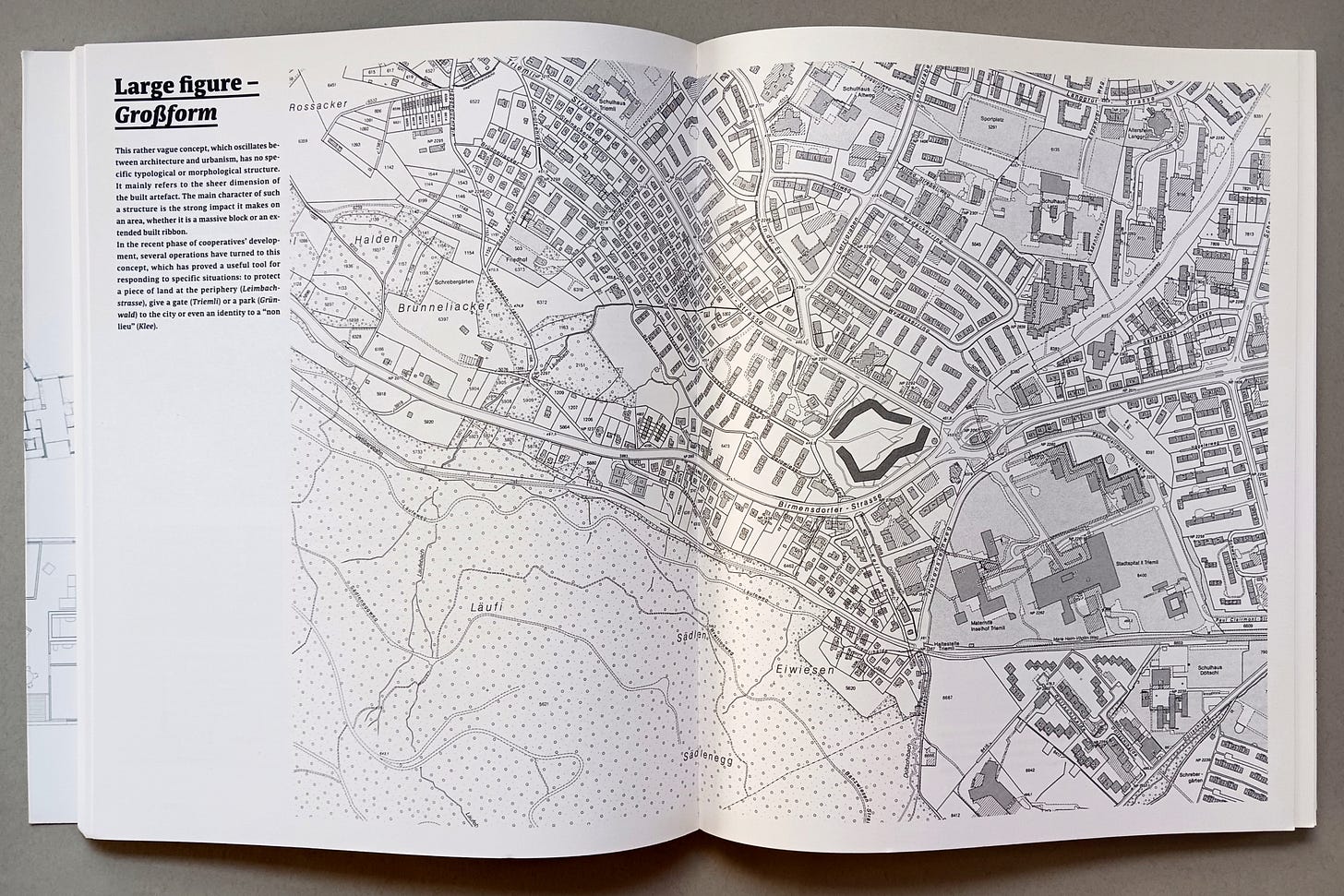

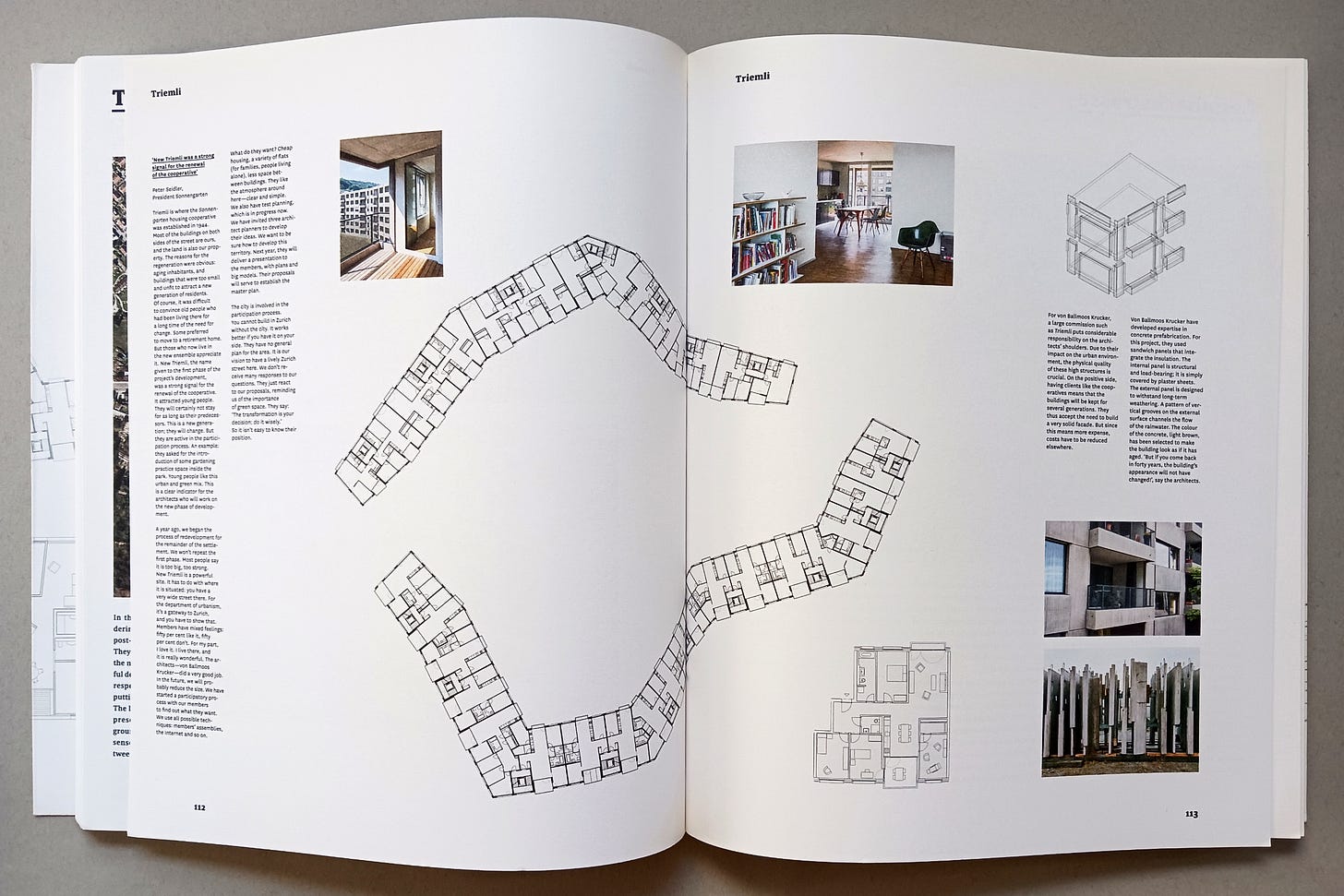

New Housing in Zurich: Typologies for a Changing Society (Park Books, 2019) is a beautifully crafted book that presents 51 housing projects spread across Zurich, some of which I was able to visit years before when in Zurich for my work with World-Architects. The projects I visited, and most of the ones in the book, are fairly large and therefore have large sites where site planning is paramount. Accordingly, site plans or aerial views are included for each of the 51 projects, as are the usual floor plans, photographs (or renderings), and project descriptions. What makes the projects remarkable beyond their architectural qualities is the fact they are predominantly middle-class and/or cooperatives — making the book a suitable reference for other places where there is a shortage of such housing, well-designed or not. Here are a few spreads from inside this great, but unfortunately hard-to-find book:

Thank you for subscribing to A Weekly Dose of Architecture Books. If you have any comments or questions, or if you have your own book that you want to see in this newsletter, please respond to this email, or comment below if you’re reading this online. All content is freely available, but paid subscriptions that enable this newsletter to continue are welcome — thank you!

— John Hill