This newsletter for the week of June 10 heads down South, specifically to Mississippi to take a look at the first book by Jackson’s Duvall Decker. From there we’ll go up the road a ways and look at a few related books from the archives. In between are the usual new books and headlines. Happy reading!

Book of the Week:

Foundations by Anne Marie Duvall Decker and Roy Decker (Buy from ORO Editions / from Amazon / from Bookshop)

“The most important project for a design studio is the design of the practice itself.”

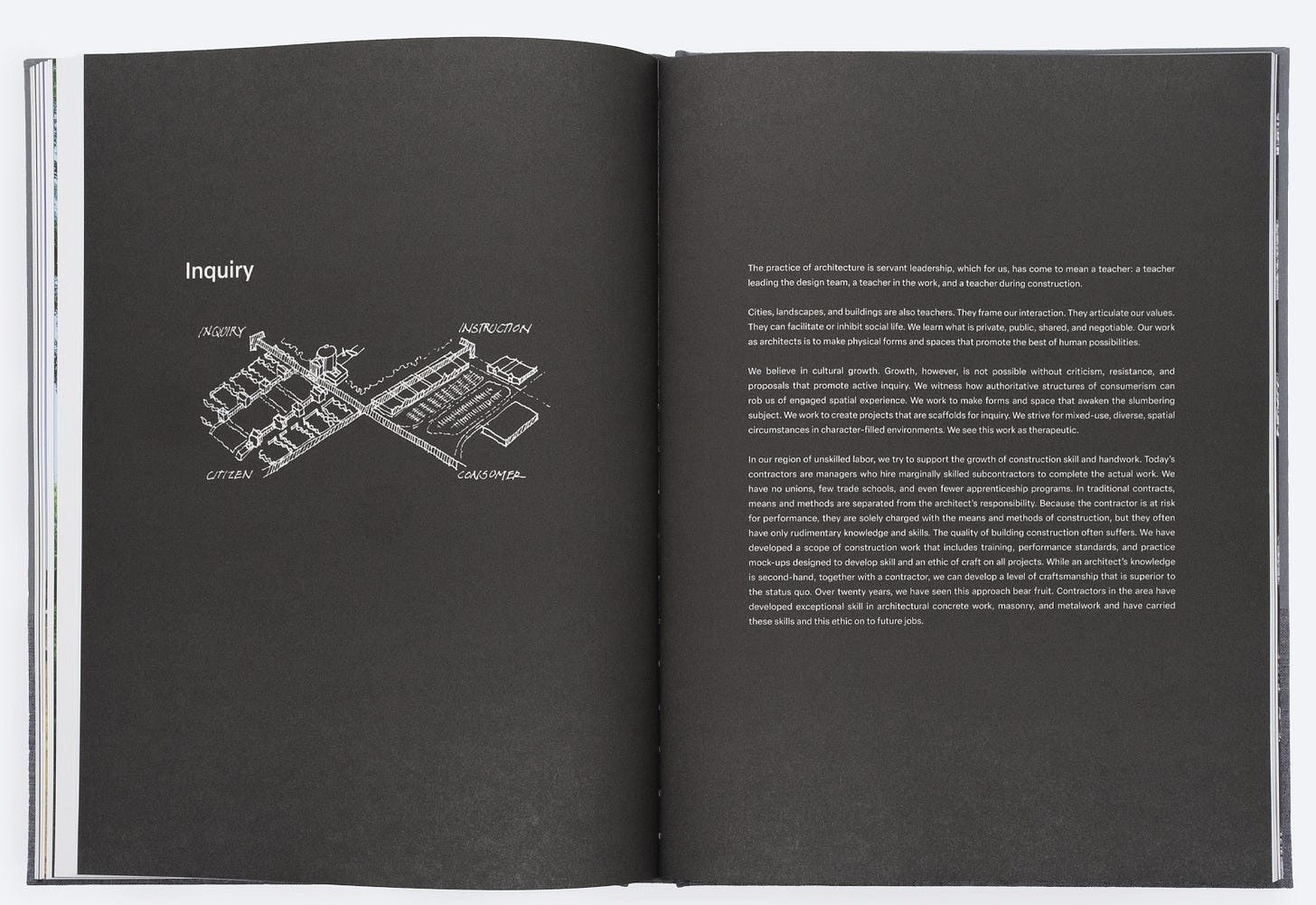

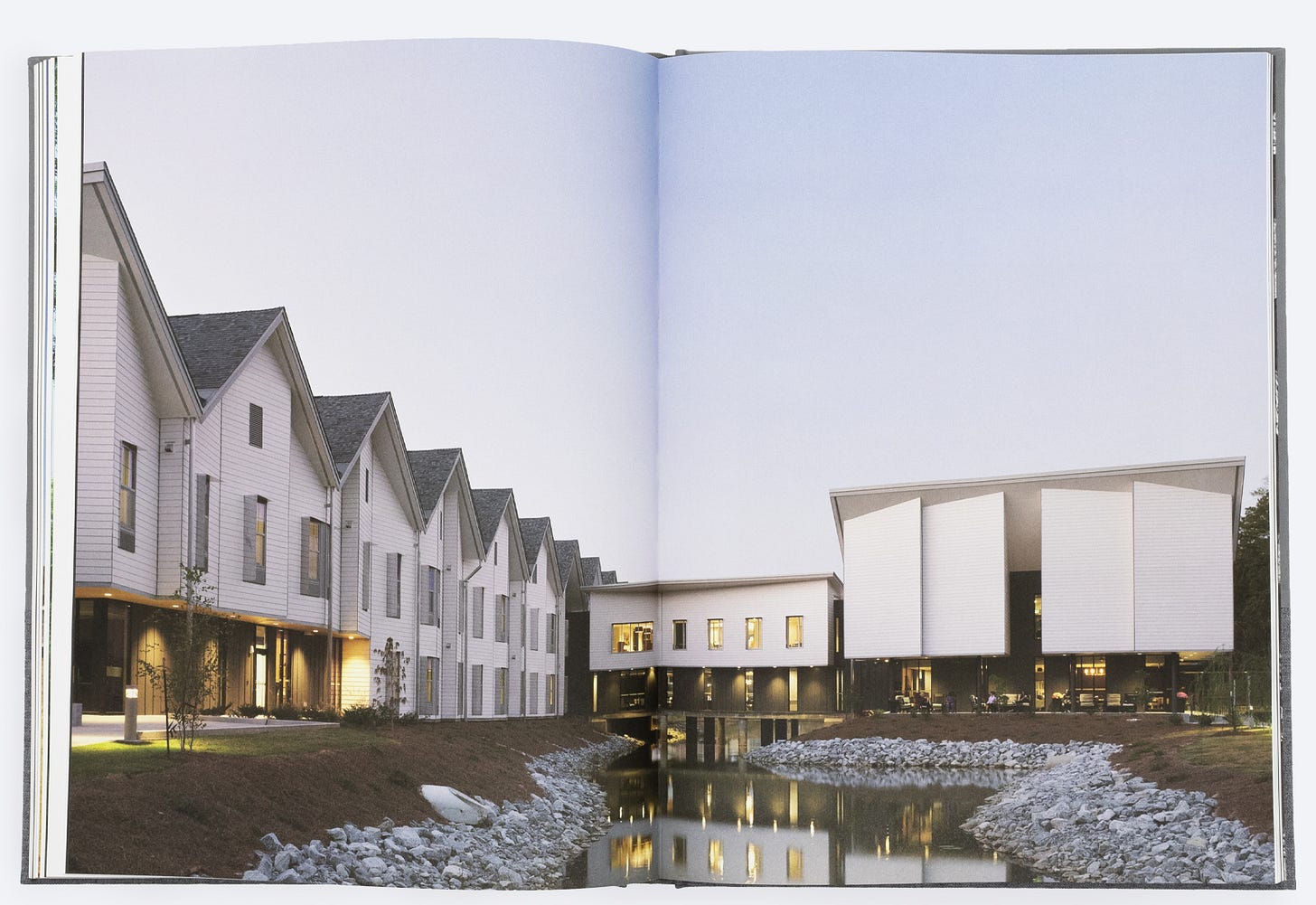

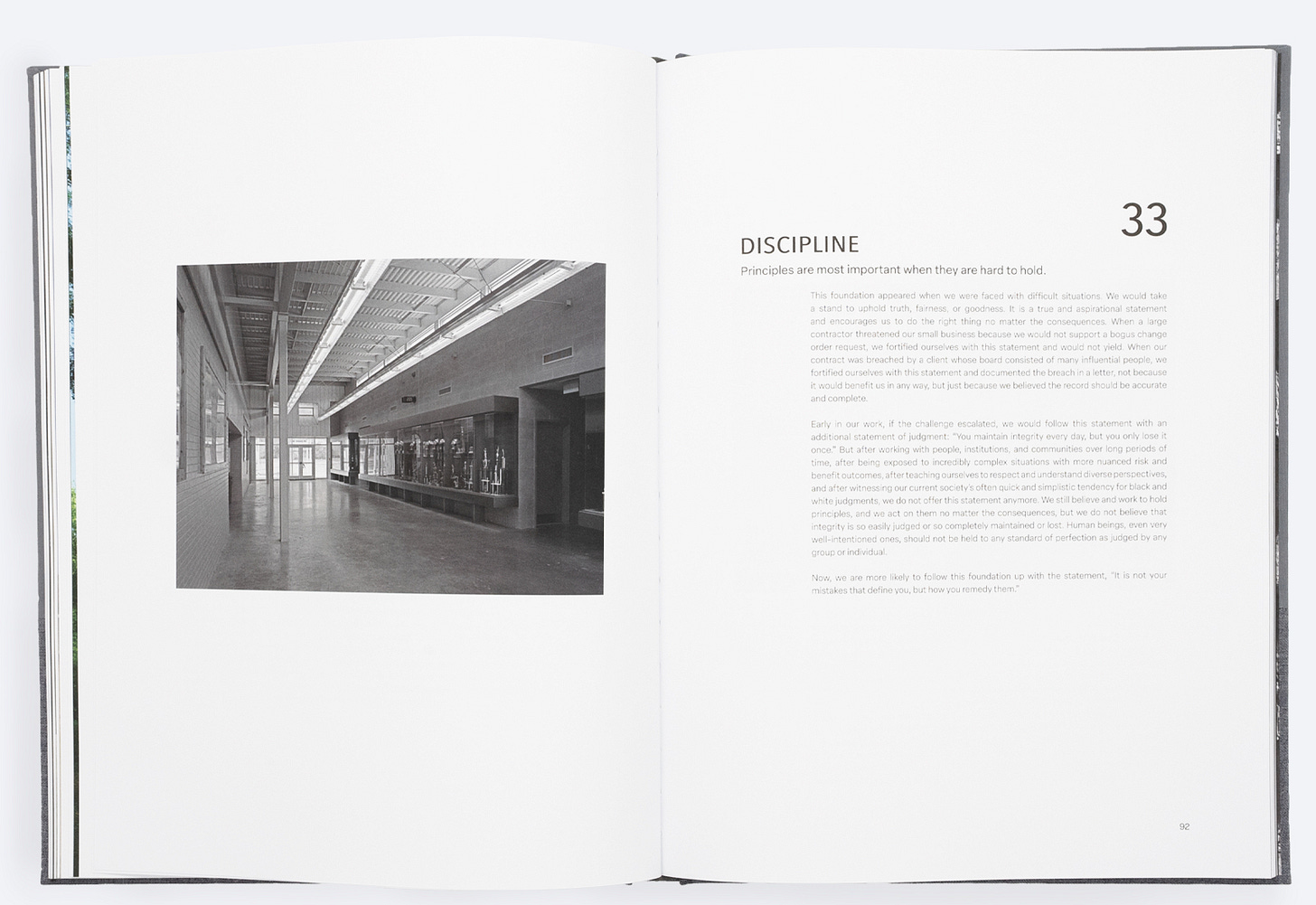

This is the first of many statements that readers encounter in Foundations, a book by and about Jackson, Mississippi’s Duvall Decker Architects. Rather than presenting some of the projects the practice has realized since it was founded by Anne Marie Duvall Decker and Roy T. Decker in 1998, the monograph released this week features “nine Propositions and fifty-three Foundations” that express how the firm works — how the practice was designed — and are offered to other architects for potential inspiration in defining their own practices. Projects are nevertheless presented, but simply and without explanation: black-and-white photographs opposite the foundations; sketches opposite the propositions; and full-bleed color photographs that follow each proposition to give the book a regular rhythm (six foundations for every proposition). The words, photographs, and sketches combine to portray Duvall Decker as in a traditional monograph, yet doing it in a way that sets Foundations apart from other architectural monographs.

As I started reading the book and realized how it is geared as much to professional practice as to architectural design, my thoughts drifted to my first job out of architecture school, specifically my first day on the job. Before I was put to work on a project, but after I got a tour of the office to get my bearings, I read the employee handbook. I no longer have that document, but I recall it defining the standards and expectations in regard to every practical aspect of the office: hours, lunch, overtime, supplies, graphic standards, attire, correspondences, moonlighting. (One of the three OfficeUS publications that accompanied the US Pavilion at the 2014 Venice Architecture Biennale actually collected and commented on such manuals.) An important thing the handbook didn’t do was define what made the firm unique, what guided it in design and business — its philosophy.

Duvall Decker’s Foundations is basically an anti-office manual, in that it is focused entirely on the intangible, philosophical aspects of the firm rather than the mundane “standards” that are shared by every practice. Yes, architects will relate to some of the anecdotes recounted across the foundations and propositions, but they will see how Duvall Decker responded to particular situations and instill their approach into the various aspects of daily work. Foundations is not the first book expressing the ethos of an architectural practice, but I’m wagering that most firms in the United States, where the average size is around a dozen employees, will find more useful statements in its pages than, for instance, The World by Design: The Story of a Global Architecture Firm by A. Eugene Kohn of KPF, a firm with 600 employees in nine offices on three continents — Duvall Decker has 17 people on its profile page (not all of them architects), much closer to the national average than KPF.

As I read through the book and added Post-it Notes to some of my favorite passages, a few things came to the fore. The references are diverse and deep, from Kenneth Frampton’s “Towards a Critical Regionalism” and Richard Sennett’s The Craftsman to Karl Popper’s Of Clocks and Clouds and The Checklist Manifesto by Atul Gawande. The language is also diverse, with memorable assertions like “create a wake of interest” and “the concrete must breathe the abstract” balanced by more grounded advice on the workings of their firm. The practical advice, in turn, is open and honest, as in a discussion on debt and fees and Duvall Decker’s own office manuals: its “Instruments of Service” and “Basis of Collaboration,” both of which acknowledge how the work of architects is social, is rooted in communities. Foundations is recommended for young architects looking to design their practices as well as practitioners who want some inspiration and an outside perspective.

Books Released This Week:

(In the United States, a curated list)

Architecture and Climate Change: 20 Interviews on the Future of Building by Sandra Hofmeister (Buy from Edition DETAIL / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — Interviews with Marina Tabassum, Shigeru Ban, Anna Heringer, and others give a sense of how buildings and cities should be designed to actually achieve decarbonization.

Architecture of Transformation in Flanders by Florian Heilmeyer and Sandra Hofmeister (Buy from Edition DETAIL / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — A presentation of two-dozen “daring transformations of existing architecture” in the Flanders region of Belgium that “are raising the bar on adaptive reuse.”

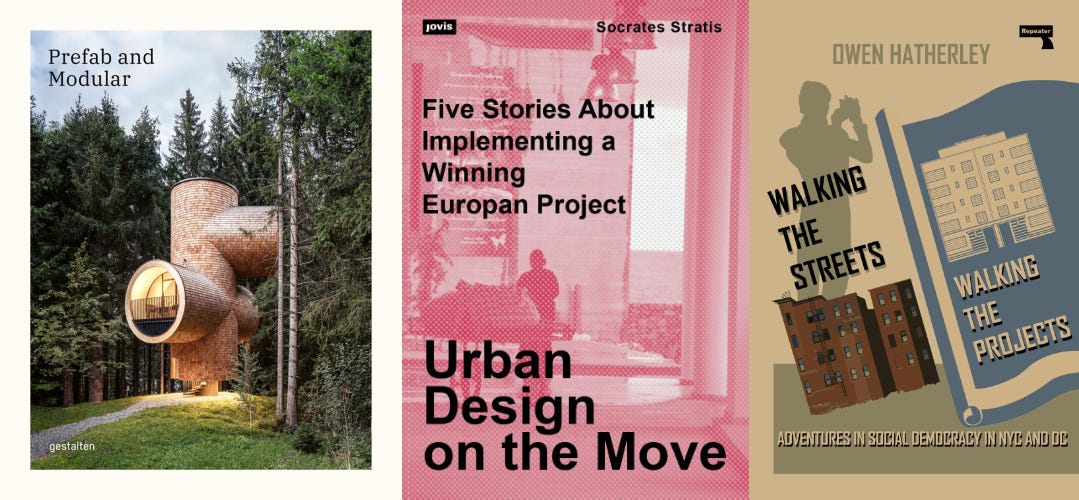

Prefab and Modular: Prefabricated Houses and Modular Architecture (Buy from gestalten / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — The latest survey of contemporary architecture from the editors of gestalten rounds up prefabricated houses and modular architecture.

Urban Design on the Move: Five Stories About Implementing a Winning Europan Project by Socrates Stratis (Buy from JOVIS / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — Mixing fact and fiction, this book tells the story of realizing a project on the waterfront in Crete that was a winner of Europan 4, written by a member of Europan’s Scientific Committee.

Walking the Streets/Walking the Projects: Adventures in Social Democracy in NYC and DC by Owen Hatherley (Buy from Repeater / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — Hatherley, the indefatigable author of numerous books, including Artificial Islands, an architectural tour of British settler colonial cities, crosses the Atlantic to walk through housing projects in New York and public transit in DC and ask “what a new generation of American socialists might be able to learn from them.”

Full disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, AbeBooks Affiliate, and Bookshop.org Affiliate, I earn commissions from qualifying purchases made via any relevant links above and below.

Book News:

Over at World-Architects, I delved into Lebbeus Woods: Exquisite Experiments, Early Years, a recent issue of Architectural Design (AD) that reveals some early work on the visionary architect/delineator that even ardent fans will be surprised by.

Air Mail profiles High Valley Books, the appointment-only bookshop run by Bill Hall out of his family’s apartment in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. I have bought a few architecture books through his website but have yet to go there in person; with many more books in his basement and upstairs than online, that will surely change.

Italy will be guest of honor at the 76th Frankfurt Book Fair taking place in October, and Stefano Boeri has designed the Italian Pavilion for the event as an Italian square, or piazza.

From the Archives:

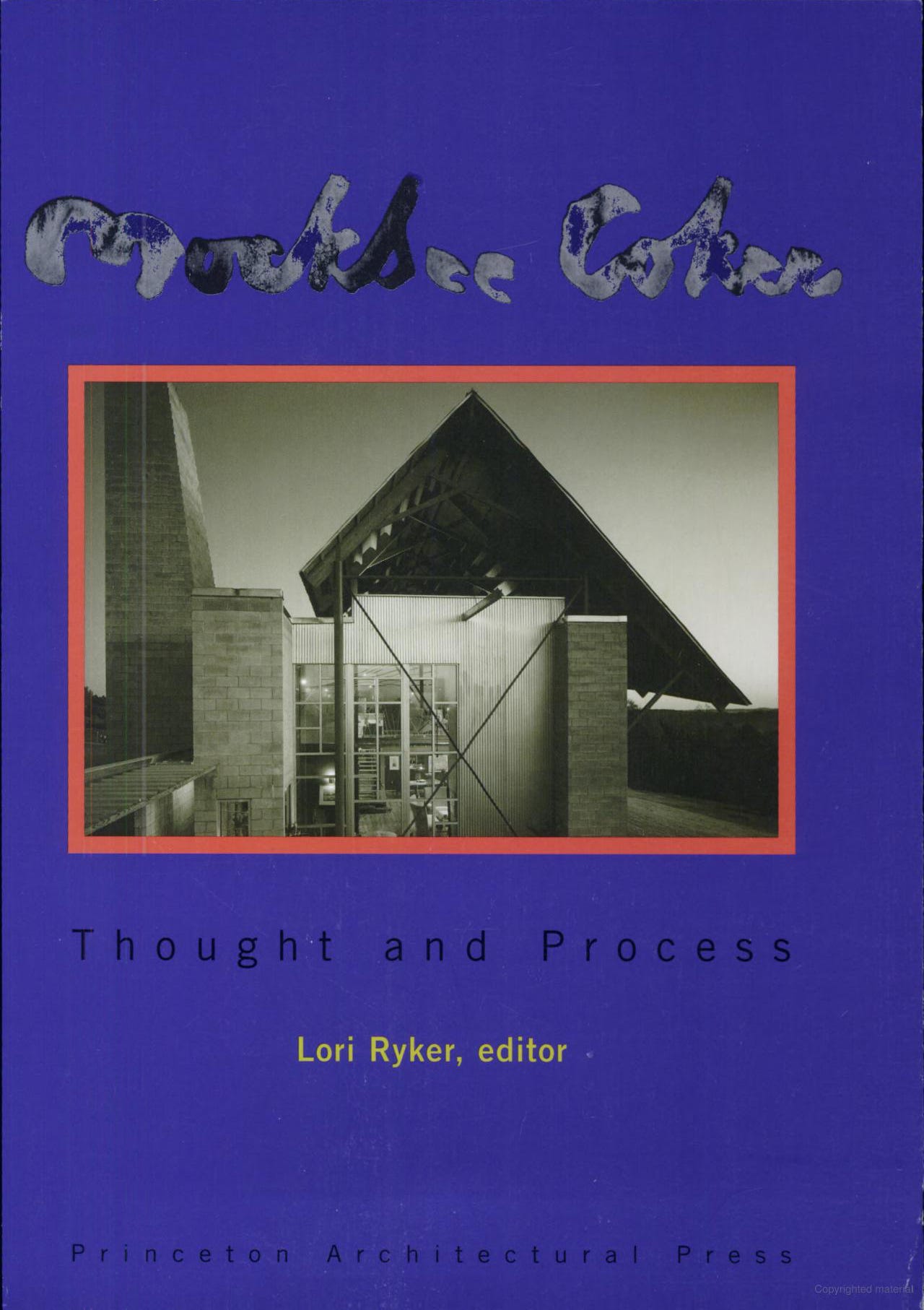

Duvall Decker may be the most well known architects based in Mississippi, but when I think of past architects from the state my mind immediately goes to Samuel “Sambo” Mockbee. Although he would become famous for the Rural Studio at Alabama’s Auburn University, Mockbee said he lived with one foot in Mississippi and one in Alabama. Born in Meridian (MS) in 1944, he taught in Greensboro (AL), lived with his wife in Canton (MS), and died in Jackson at the end of 2001. My discovery of Sambo came via Mockbee Coker: Thought and Process, the 1995 monograph edited by Lori Ryker and published by Princeton Architectural Press that documents the partnership of Mockbee and Coleman Coker. The primarily residential projects in the book, such as the Cook House in Oxford, Mississippi, are quirky, likable variations on the vernacular architecture of the American South. They were created by a pair of architects rooted in the South (Coker was born in Memphis) but quite different in temperament, at least as evidenced by their contributions to the book: Coker’s “An Intent of Constructing : [of] Constructing an Intent” is full of the dense theorizing that was popular at the time, while Mockbee’s interview with Ryker and Randolph Bates exudes his humble nature, his emotional honesty, and the belief in social responsibility that found its greatest fruition at Rural Studio.

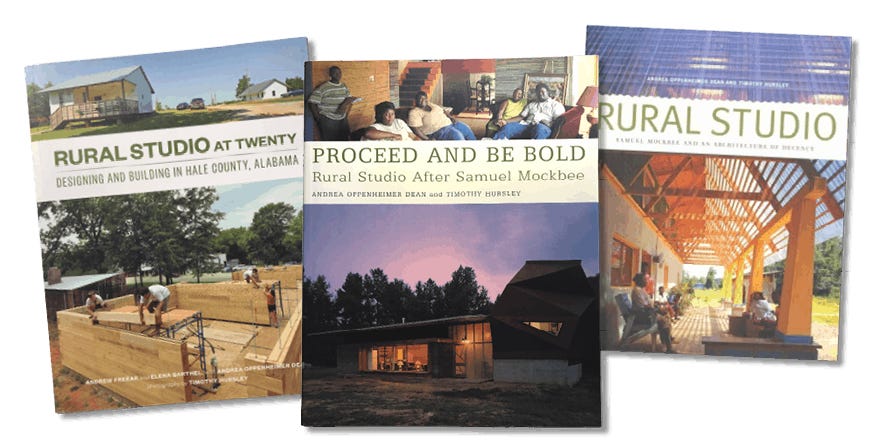

While the partnership of Mockbee and Coker came to a halt on December 30, 2001, when Mockbee died at the age of 57, the Rural Studio that he and Dennis K. Ruth established in 1993 at Auburn University continued after Mockbee’s death — it continues to this day, now in its fourth decade. The importance of Mockbee in the off-campus, hands-on program that saw students designing and building houses and community buildings for the residents of Hale County, Alabama, is evident in the name of its first monograph: Rural Studio: Samuel Mockbee and an Architecture of Decency. The book, written by Andrea Oppenheimer Dean and photographed by Timothy Hursley, came out in early 2002 but was printed before Mockbee’s death so didn’t mention Mockbee’s passing. Perhaps because of this, it didn’t take long for Dean and Hursley to follow it three years later with Proceed and Be Bold: Rural Studio After Samuel Mockbee, whose subtitle again expresses Mockbee’s outsized role in the program’s vision.

By the time of the second book’s publication in 2002, Andrew Freears was in place as director of Rural Studio (Ruth helmed it for just six months after Mockbee’s death). It would be another nine years for the publication of a third book, Rural Studio at Twenty: Designing and Building in Hale County, Alabama, also by Dean and Hursley but this time accompanied by Rural Studio’s Freear and Elena Barthel; the book marked the studio’s 20th anniversary. In addition to the presence of Dean and Hursley, the matching trim sizes, french-fold paperback formats, and consistent publisher turned the books into something of a series. But given that Dean died at the end of 2001 and Princeton Architectural Press is now PA Press, a division of Chronicle and shell of its former self, it looks as if these three books will remain a trilogy. And that’s fine, since together they are exemplary documents of some of the most innovative architecture in the United States — architecture that happened to be designed and built by students for the rural poor in the Deep South.

Thank you for subscribing to A Weekly Dose of Architecture Books. If you have any comments or questions, or if you have your own book that you want to see in this newsletter, please respond to this email, or comment below if you’re reading this online. All content is freely available, but paid subscriptions that enable this newsletter to continue are welcome — thank you!

— John Hill