This newsletter for the week of June 17 takes a trip to Plano, Illinois, to the Edith Farnsworth House, the nearly 75-year-old house designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe for Dr. Edith Farnsworth that is the subject of a sweeping new monograph. Mies and Farnsworth are present in some books pulled from the archive, while the usual new releases and headlines are in between. Happy reading!

Book of the Week:

The Edith Farnsworth House: Architecture, Preservation, Culture by Michelangelo Sabatino (Buy from Monacelli Press / from Amazon / from Bookshop)

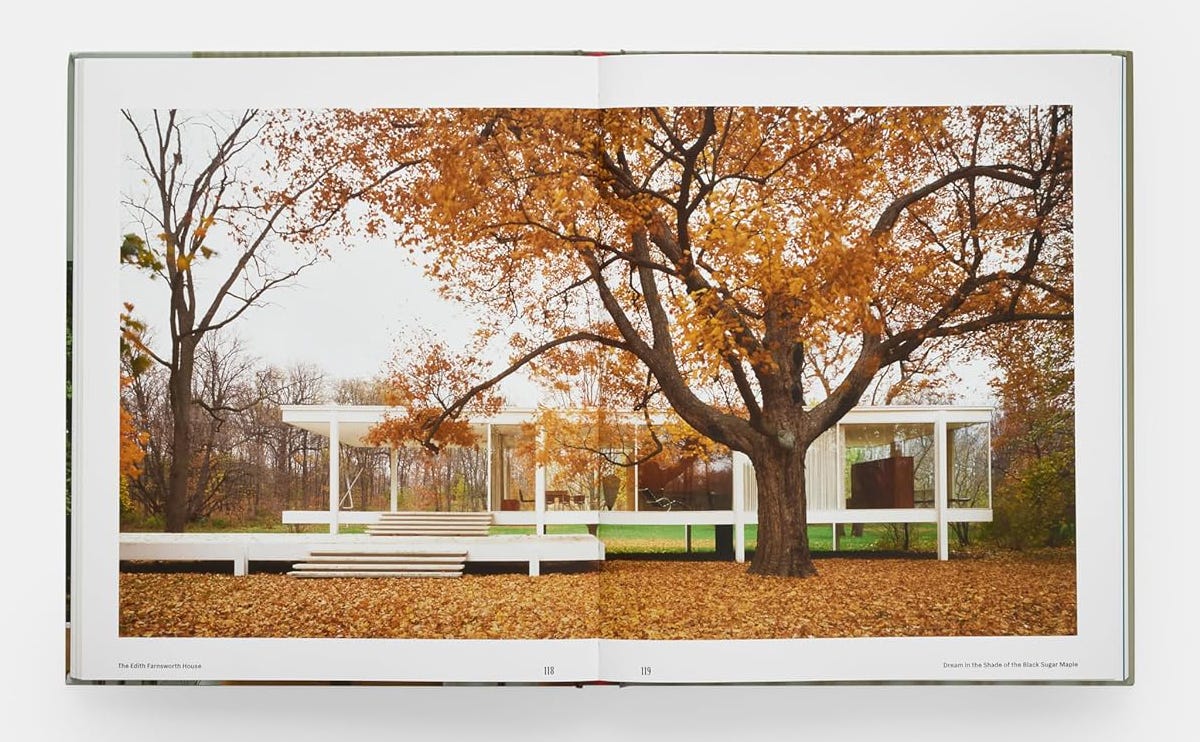

It is near impossible to write about Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House in Plano, Illinois, without discussing Philip Johnson’s Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut — and vice versa. The two architecturally similar, rectilinear glass houses were built two years apart — Johnson’s in 1949 and Mies’s in 1951 — and Johnson was openly inspired by Mies’s house, having seen it while he was curating a show on Mies at MoMA in 1947. The differences between the houses are more interesting than their similarities, most obviously in the ways they relate to the ground they are built upon (lifted vs. at grade), the colors of their steel (white vs. black), and the way they treat that most important practical space, the bathroom (brick cylinder vs. wood cube). Key among the differences was Mies being hired by Dr. Edith Farnsworth, a successful physician and professor of medicine, and Johnson being his own client. As such, Johnson provided himself a separate Guest House, or Brick House, that allowed for privacy, while Mies played down this and other practical aspects of the one-room weekend house in favor of adherence to his philosophical principles of universal architecture.

Fittingly, both houses are now owned and operated by the National Trust for Historic Preservation, though the nonprofit came to this situation in different ways. Johnson, whose New Canaan estate grew to 49 acres from 1949 until his death in 2006, donated his estate to the National Trust in 1986, who took it over after he died and opened it to the public in 2007. The Farnsworth House, on the other hand, was on the auction block in 2003, after its longtime, post-Dr. Farnsworth owner, Lord Peter Palumbo, was unable to sell it directly to a stingy State of Illinois two years earlier. Preservationists were worried but ultimately won, with the National Trust and Landmarks Preservation Council of Illinois raising the money to win the auction and opening the house to the public in 2004.

The worry was justified because, unlike Johnson’s estate in relatively benign Connecticut, the site of the Farnsworth along the banks of the flood-prone Fox River west of Chicago made the prospect of moving the house by its new owner a distinct possibility; and who knew if the new owner would have let the public in, which Palumbo did when he was away. But if Farnsworth had not come to Mies after buying those many acres from Colonel McCormick, he would not have designed an elevated house or one with perimeter glass walls framing the landscape around it. Site and house, in other words, are one, regardless of the fact the house should have been raised higher than it actually was, as flood damage and restoration in recent decades have proven (for Mies, again, proportion was more important than practical concerns).

In the years since the National Trust has been offering tours to the Glass House and the Farnsworth House, it has been holding exhibitions, installing temporary artworks, and otherwise using these sites and buildings for exploring the changed meanings of the houses, their architects, and their patrons. Recent societal shifts have brought conversations around previously overlooked subjects to the fore, including Johnson’s embrace of Fascism and the difficult relationship between Mies and Farnsworth. Recent biographies of the two architects, most notably Mark Lamster’s The Man in the Glass House and the revised edition of Franz Schulze’s critical biography of Mies (see the bottom of this newsletter), discussed these subjects via newly unearthed materials: Schulze, writing with Edward Windhorst, highlighted parts of a transcript of an early-1950s court case over the Farnsworth House.

Of the books that have been devoted to the Farnsworth House, and there are quite a few, they tend to focus exclusively on Mies, the houses’s design, and photographs of it. The combination of contemporary social concerns, scholarship revisiting long-accepted histories, and exhibitions, such as Edith Farnsworth Reconsidered, makes Michelangelo Sabatino’s sweeping The Edith Farnsworth House (the National Trust subtly changed the name in 2021) understandable and necessary. Sabatino and his fellow contributors look at the house from a much wider lens than the authors of previous books.

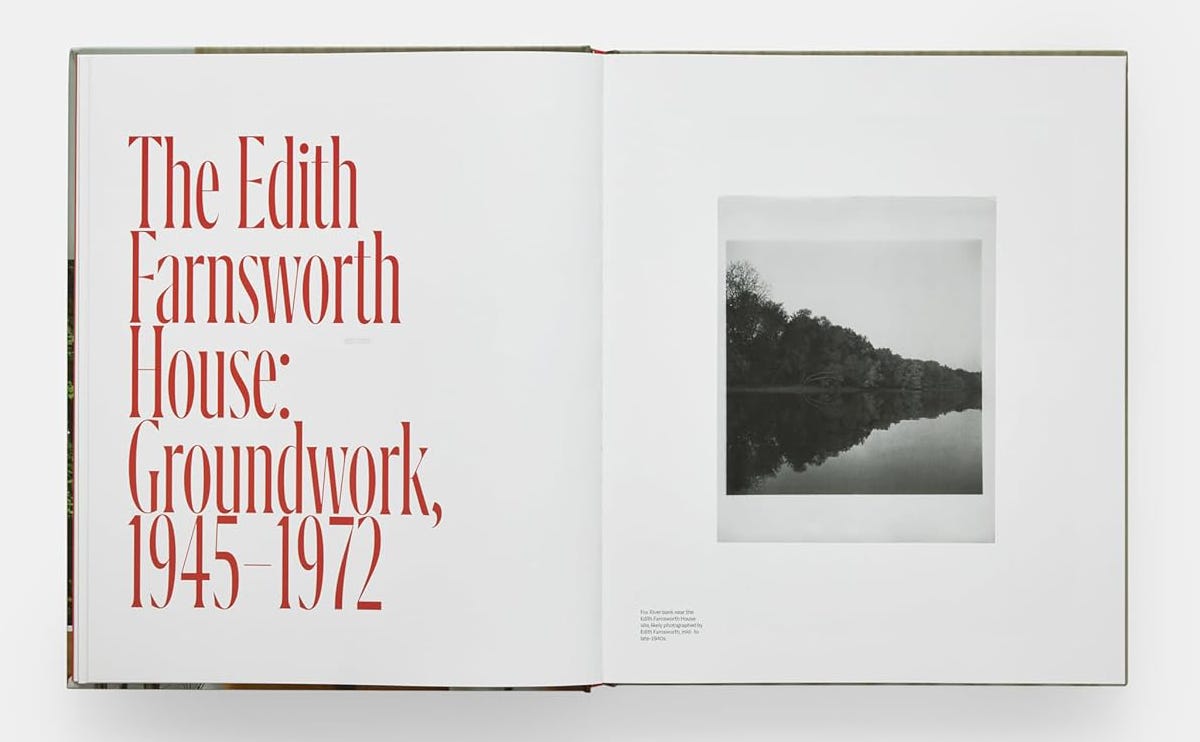

Sabatino’s book is published by Monacelli Press, which every year looks more and more like its owner since 2020, Phaidon, so appropriately it is a large coffee table book with many illustrations and not a small cover price (though half of what another Mies book by Phaidon that happens to be rereleased this week goes for). But The Edith Farnsworth House is as smart with the texts as it is generous with the images. There are opening and closing essays by Sabatino that respectively explore how the house’s myth has depended on its representation and how the house has survived after its original owner sold it, as well as another essay (revised from Modern in the Middle) that situates the house within the broader context of mid-20th century residential architecture in the Chicago metropolitan area.

The other contributions come from historian Dietrich Neumann, who has written a few books on Mies, landscape architect Ron Henderson, current Edith Farnsworth House executive director Scott Mehaffey, and Glass House (again!) chief curator and creative director Hilary Lewis. The book also includes excerpts from Edith Farnsworth’s unpublished memoirs, quotes from Mies about the house, an interview with Lord Peter and Lady Hayat Palumbo, and an interview with architect Dirk Lohan, Mies’s grandson. Sweeping, as I wrote above. The book is a perfect introduction to the house for people who have no familiarity with it, but it is also a valuable addition to the library of architects who thought they knew everything there was to know about one of the most famous works of residential architecture, modern or otherwise.

Books Released This Week:

(In the United States, a curated list)

Beton & Nicht Beton by Felix Sommer (Buy from JOVIS / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — A monograph on Felix Sommer and SB5ÜNF, the Berlin company that specializes in concrete and has reportedly worked on more than 1,600 built projects; just a few are presented here. Note that the book is in German but is primarily photographs, and the book also comes in a special “hardcover” edition with front and back covers made from 5mm layers of concrete.

Climate Action for Busy People by Cate Mingoya-LaFortune (Buy from Island Press / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — Climate change is so overwhelming that it’s easy to do nothing and hope for the best from world leaders, energy companies, and global corporations. Not to planner and community organizer (and Queens native!) Mingoya-LaFortune, who believes “the wisest and most lasting adaptation solutions originate at the local level.”

Leon Battista Alberti: Writer and Humanist by Martin McLaughlin (Buy from Princeton University Press / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — McLaughlin, who previously wrote a study of Italo Calvino, examines the overlooked literature produced by Alberti, from early Latin works to his “vernacular humanism” in Italian and famous De re aedificatoria.

Mies by Detlef Mertins (Buy from Phaidon / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — Phaidon is rereleasing — “now available with a stunning new cover” — the excellent historical monograph on Mies van der Rohe by Detlef Mertins (1954–2011) that was released posthumously in 2014. (See also the bottom of this newsletter.)

On Architecture and Greenwashing: The Political Economy of Space Vol. 01 edited by Charlotte Malterre-Barthes (Buy from Hatje Cantz / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — The first volume in a planned series by EPFL's RIOT (Research and Innovation on Territory) lab asks if real sustainability in architecture is possible and invites contributors to “[explore] ways to correct course in the face of a climate crisis of unprecedented magnitude—beyond greenwashing.”

The Pocket Universal Principles of Interior Design: 100 Ways to Develop Innovative Ideas, Enhance Usability, and Design Effective Solutions by Kelly Harris Smith and Chris Grimley (Buy from Rockport Publishers / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — Out this week is the compact, pocket edition of the 2022 Universal Principles of Interior Design, which “presents 100 concepts and guidelines that are critical to a successful visualization and application of interior design.”

Full disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, AbeBooks Affiliate, and Bookshop.org Affiliate, I earn commissions from qualifying purchases made via any relevant links above and below.

Book News:

To Helen Macneil, the writings in Five Critical Essays on Architectural Ethics, edited by Austin Williams, “challenge the prevailing status quo, urging architects to reclaim their agency and engage in genuine ethical inquiry instead of blindly adhering to fashionable dogmatic frameworks.”

Two pieces on former New York Times architecture critic Paul Goldberger: Vladimir Belogolovsky interviews him at STIR and, over at Curbed, Fred Bernstein visits him and other architecture types at 870 United Nations Plaza, where Goldberger has lived since last August.

Publishers Weekly looks ahead to fall 2024 releases in art, architecture, and photography, putting I.M. Pei: Life Is Architecture in its Top 10 and including books about Santiago Calatrava, Paul Rudolph, and Frederick Kiesler and books by Aaron Betsky and Vishaan Chakrabarti in its longlist.

From the Archives:

Back in 2015, I reviewed a few Mies books on my blog and two of them were thorough histories of the titanic figure: Mies van der Rohe: A Critical Biography, New and Revised Edition by Franz Schulze and Edward Windhorst and Mies by Detlef Mertins. Unknown to me at the time, Luis Fernández-Galiano grouped the same two books together a year earlier, calling them “essential works.” He wrote that Mies van der Rohe, first written by Franz Schulze in 1985 and greatly expanded with Chicago architect Edward Windhorst in 2013, “remains the best available biography of the Aachen-born master” and that Mies by Detlef Mertins was “sure to eventually become a classic” (that the latter is being rereleased this week is something of a validation of that statement). What did I write about the two books? I recommended Schulze and Windhorst's book to those with little familiarity of Mies and those who know his buildings but not his story, and called Mertins’s book “a thorough historical monograph that is given the Phaidon touch, meaning it was made big and illustrated profusely,” and in which “his historical skills shine, aided by numerous photographs and drawings.” Each book focuses on Mies’s seminal works, so Farnsworth is there, accompanied by newly discovered trial transcripts in the case of Critical Biography and discussed alongside Crown Hall in one chapter of Mies about Mies’s “pursuit of a clear construction.”

An important precedent for the wider takes on the architect-client relationship in the The Edith Farnsworth House and the revised edition of Schulze’s Mies bio is Women and the Making of the Modern House: A Social and Architectural History by Alice Friedman, first published in 1998. Although the photogenic Farnsworth House is on the cover of both the first hardcover edition and the 2007 paperback, the title indicates how the book’s subject is larger than just this one house. In addition to Farnsworth, Friedman devotes chapters to houses by Wright, Rietveld, Corbusier, Neutra, and Venturi in which women were clients. The chapter on Farnsworth even takes a detour to Johnson’s Glass House in New Canaan, an approach that elevates the important role of Dr. Edith Farnsworth in the making of her weekend house and the differences of the two modern houses that are often lumped together. Friedman’s thorough dive into the Farnsworth House examines, among other things, the strife between architect and client and Farnsworth’s difficulties in living in the house, but ultimately the author finds more sympathies with Mies: “Having seen the model and the plans, Farnsworth ought to have known better. She could see that the house was going to have glass walls, so why was she so surprised when they finally appeared?” Indicative of her bitterness and desire to put it behind her, after she sold the house to Lord Palumbo and retired to Italy, Farnsworth lived in a house near opposite to the one in Plano that still bears her name.

Thank you for subscribing to A Weekly Dose of Architecture Books. If you have any comments or questions, or if you have your own book that you want to see in this newsletter, please respond to this email, or comment below if you’re reading this online. All content is freely available, but paid subscriptions that enable this newsletter to continue are welcome — thank you!

— John Hill