This newsletter for the week of June 24 takes a look at a new book from James Biber that presents 366 architects and designers: one for each day of the year, based on their days of birth. I stretched to pull a couple books from my archive that are related to The Architect and Designer Birthday Book. Those are at bottom, with the usual headlines and new releases in between.

Book of the Week:

The Architect and Designer Birthday Book by James Biber (Buy from PA Press / from Amazon / from Bookshop)

Of the many one-thing-per-page books that survey buildings or architects or some other subject, my favorites are the one whose format forces the authors or editors to make difficult decisions. Although my books 100 Years, 100 Buildings and 100 Years, 100 Landscape Designs were technically one-thing-per-two-pages books, the way of surveying the history of buildings and landscapes by picking one thing per year (based on completion or opening, typically) over the course of 100 years forced me to make judgments: is MAXXI by Zaha Hadid Architects, to take a 2010 example, more important than SANAA’s Rolex Learning Center? Every book, regardless of its subject, will have omissions, but in the context of books like mine and James Biber’s The Architect and Designer Birthday Book, which is being released this week and highlights one architect or designer (or artist or photographer or writer, in fact) born each day across a 366-day year, the omissions say almost as much about the end product as do the inclusions.

First, the inclusions. Biber is an architect, principal of Biber Architects, but before he established his namesake firm about fifteen years ago he was a partner at Pentagram, the famed design firm that was founded in London in 1972 and now has a handful of offices, including New York City, where Biber worked and designed its previous digs. This background points to the logic of creating a book — one born from a year-long Instagram projects, it should be noted — that looks at architects as well as industrial designers, graphic designers, and others who are referred to with “designer” before their name. Think of a famous architect and they’re probably in the book, but they most likely sit on the page beside a lesser known architect or someone in another design field. PoMo architect Michael Graves, born on July 9, faces Harvey Ball, who was born on July 10 and later designed the iconic smiley face. A flip through the book yields plenty such juxtapositions — ones that are part of a continuum on Biber’s Instagram but take on extra meaning given how books are structured into spreads: one page opposite another.

The omissions are many, based on the fact that there are way more than 366 architects and designers worth discussing in such a survey. Yet, that certain people are omitted comes to the fore in seeing which people are included. Both Alvar Aalto (January 25) and Aino Aalto (February 3) are there, as are, curiously and somewhat humorously, both James Biber (March 3) and his mother, Ruth Biber (March 23), but Ray Eames does not have her own entry, nor does Robert Venturi (a reversal of what was the norm!) or Sibyl Moholoy-Nagy or Frank Lloyd Wright — yes, Frank Lloyd Wright, whose second son, John, is in the book instead. The elder Wright, arguably the greatest American architect ever, was born on June 8, but Biber puts Bruce Goff, Wright’s disciple, on that day instead: “Today is a dual birthday,” he writes. “Goff was thirty-seven years Wright’s junior but one of the only architects Wright deigned to endorse.”

These examples aren’t used to criticize Biber’s omissions or inclusions, but to point out that as soon as an author (or Instagrammer) adopts a format that requires one choice over another, the selection says as much about the author as their subjects. The day-by-day, page-by-page judgments add up to a whole that is nuanced by personal preference, be it planned, random, or something else. In the case of The Architect and Designer Birthday Book, Biber writes in a way that is personal, often describing why the person is important to him, but doing it in a way that keeps the focus on the work of that person. Biber is also opinionated, if not critical — in the sense of expressing his reasoning behind a statement of preference, something that is admittedly hard to do in a thing-per-page book — and those opinions foreground how the 366 architects, designers, and other creatives were selected because they are important to Biber.

What I like about the book is the way it can be dipped into in various ways and also be read in various ways. Readers could open it to the date they first got the book and use the attached ribbon bookmark to keep track and read it day-by-day, like an architecture desk calendar. They could start at the beginning of the year and look at it in larger chunks, going chronologically throughout the year. They could jump in randomly, reading Biber’s short bios and personal takes as they go, or skim the index to take a peek at their favorites or flip to ones they’ve never heard of. The book is a bit like an encyclopedia or gazetteer with its own unique format.

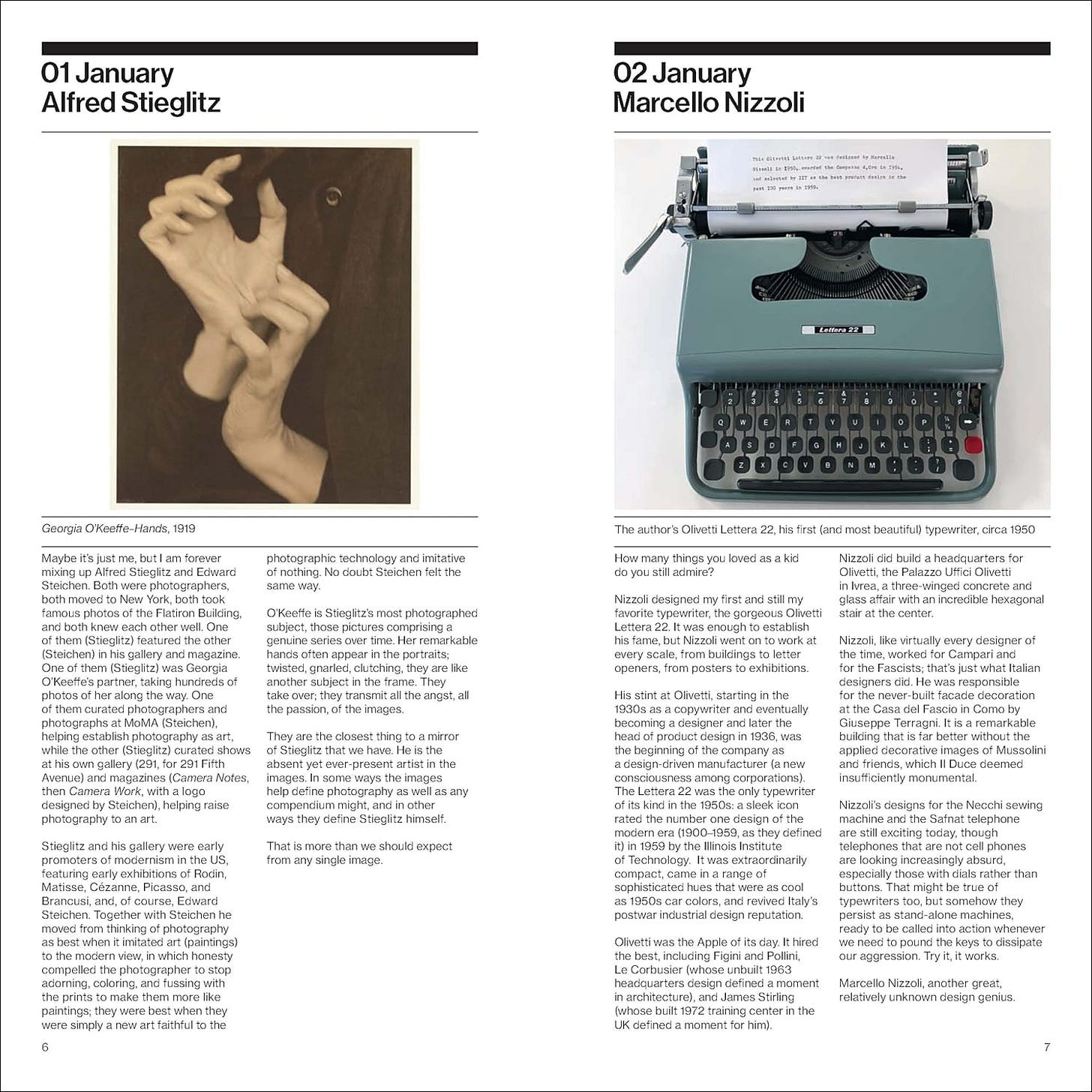

What I don’t like about the book is, sadly, its execution. The design by Pentagram’s Michael Beirut is logical, consistent, highly effective, and beautiful. I even like the metallic finish on the cover, but I don’t like the flexicover, which combines with the binding to make the whole more snap-shut rather than lay-flat; with the day-by-day format, I feel like the latter would have made more sense, would have made the book a better desk-side companion. In terms of images, Biber’s original Instagram posts in 2021 took advantage of the app’s swipe feature and lackadaisical concerns over copyright to show numerous images of the subject’s output, be it a building or some other relevant design. But illustrated books and copyright work differently, so each entry has one image and sometimes it isn’t even of a thing that day’s designer created. Too many illustrations are tangential, be it something like “actual camels, unlike the artworks created by Nancy Graves in the 1960s and 70s” (December 23) or the occasional quotes in lieu of images: “Why bother getting a passport, when I can do this anytime I feel like it?” (Joseph Cornell, December 24). But books still function better than apps, websites, or other digital equivalents as archives, and Biber’s Birthday Book is a really good archive, warts and all, of a really interesting project.

Books Released This Week:

(In the United States, a curated list)

Architecture and the Public World by Kenneth Frampton, edited by Miodrag Mitrašinovic (Buy from Bloomsbury / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — An anthology of nearly thirty essays written by historian Kenneth Frampton from the 1960s to today, with just a small amount of overlap with the earlier Labour, Work and Architecture (Phaidon, 2002) collection.

Earth, Sky & Water: Houses in the Nordic Style by Mette Lange (Buy from Thames & Hudson / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — A monograph with fifteen houses designed by Danish architect Mette Lange, organized according to their locations: "By the Water," "In the Forest," and "In the Countryside."

Everlasting Plastics edited by Tizziana Baldenebro, Lauren Leving, Joanna Joseph, and Isabelle Kirkham-Lewitt (Buy from Columbia University / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — The team that curated Everlasting Plastics, the US Pavilion at the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale, continues to explore "the infinite ways in which plastics permeate our bodies and our world" with this book of the same name.

The Mother Tongue of Architecture: Selected Writing from Kazi Khaleed Ashraf by Kazi Khaleed Ashraf (Buy from ORO Editions / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — Critical essays by the director of the Bengal Institute for Architecture, Landscapes and Settlements in Dhaka on topics that range from phenomenology and landscapes to ancient India and the architecture of Balkrishna Doshi.

Tatiana Bilbao ESTUDIO by Tatiana Bilbao (Buy from Applied Research & Design / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — The latest in the Knowlton School’s (OSU) Source Books in Architecture series presents Tatiana Bilabo in conversation with students while documenting a series of projects.

Full disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, AbeBooks Affiliate, and Bookshop.org Affiliate, I earn commissions from qualifying purchases made via any relevant links above and below.

Book News:

Over at World-Architects, I rounded up four first-time monographs on four firms, all recently released: on Alison Brooks Architects, Duvall Decker Architects, Field Architecture, and Irving Smith Architects.

Books behind paywalls: Edwin Heathcote rounds up four of the best summer reads in architecture and design at the Financial Times, and the editors of Architectural Record select the best monographs in 2024, so far.

The Daily Star features an excerpt from Adnan Zillur Morshed's forthcoming book on Shamsul Ware, "a teacher who inspired generations of architects" in Bangladesh.

From the Archives:

Continuing the calendar focus of this week’s book of the week, on this week in 2006 — on this day, June 24, to be precise — I got married. June 24 is also when Dutch designer and architect Gerrit Rietveld was born, but 118 years earlier, in 1888. I was made aware of his date of birth in The Architect and Designer Birthday Book, in which James Biber discusses Rietveld’s furniture as well as his famous Rietveld Schröder House built in Utrecht in 1924. Biber calls the house “one of the truly funny constructions in the modern era,” since it was added to the end of a row of traditional houses “like a frozen explosion,” and he illustrates Rietveld’s birthday with his Red and Blue Chair (1917) photographed inside the house, much as on the cover of The Rietveld Schröder House by Paul Overy, Lenneke Büller, Frank den Oudsten, and Bertus Mulder. The photograph on the cover of this 1988 book was taken by den Oudsten in 1987, following a major restoration of the house led by Mulder, a former collaborator with Rietveld, who died in 1964. The book features an essay by Mulder on the restoration, an interview that Büller and den Oudsten conducted in 1982 with Rietveld’s client, Truus Schröder-Schräder (accompanied by many more photos by den Oudsten), and an introductory essay by Overy. These contributions delve into the house’s architecture, furnishings, clients, and preservation to paint a comprehensive portrait of the iconic house in a slim, 128-page package.

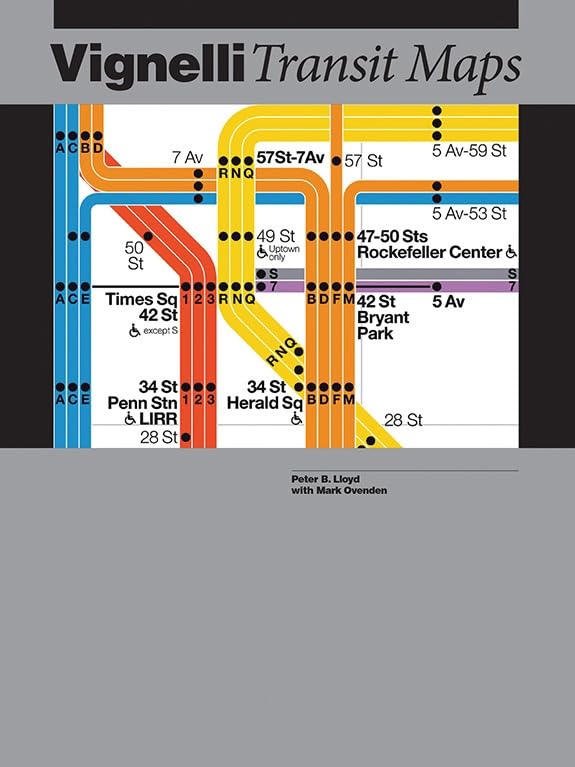

One of the spreads from James Biber’s The Architect and Designer Birthday Book at the top of this newsletter shows the January 10 birthday of graphic design Massimo Vignelli, accompanied by an illustration of the New York City subway map that Vignelli, a principal at Unimark at the time, designed for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Even though the MTA only used the map for six years, revising it a few times in the interim, it became an icon of graphic design and was eventually resurrected and reworked, first in 2008 for Men’s Vogue, and then in 2011 for the MTA’s Weekender web page. Then in 2012 came Vignelli Transit Maps by Peter B. Lloyd with Mark Ovenden, an exhaustive history of Vignelli’s designs for the NYC subway map. Across seven chapters, the authors look at circumstances that led up to the 1972 map, the design of the map itself, its reception and reasons for its cessation, as well as its influence and later rebirth this century. One would be hard-pressed not to call the book the definitive history of its subject, but ten years after the authors recounted in one chapter that a heated 1978 debate at Cooper Union between Vignelli and John Tauranac — the former promoting an abstract, modernist approach, the latter arguing for traditional, pragmatic mapmaking, and winning out — yielded no known recording or transcript, a recording was found. It was turned into a book, The New York Subway Map Debate At Cooper Union April 20, 7:30 pm, further complementing the story of an iconic design that continues to enthrall and persevere.

Thank you for subscribing to A Weekly Dose of Architecture Books. If you have any comments or questions, or if you have your own book that you want to see in this newsletter, please respond to this email, or comment below if you’re reading this online. All content is freely available, but paid subscriptions that enable this newsletter to continue are welcome — thank you!

— John Hill