This newsletter for the week of July 15 hones in on the work of Carlo Scarpa, the subject of a new book of photographs taken by architect Cemal Emden. That “Book of the Week” is up top, while at bottom are a couple related books from the archive — one on Scarpa and one by Emden. In between are the usual book-related headlines and new releases. Happy reading!

Book of the Week:

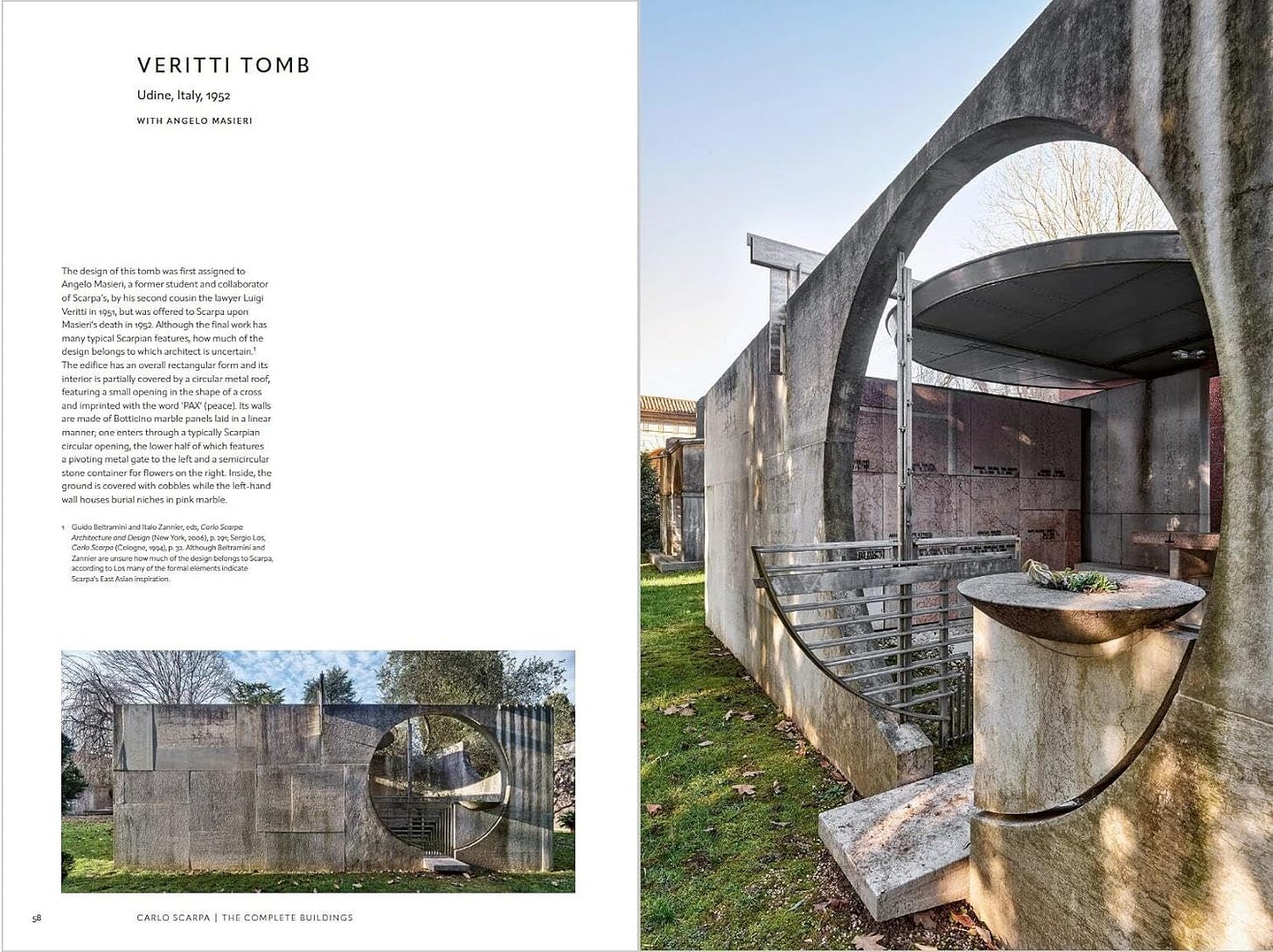

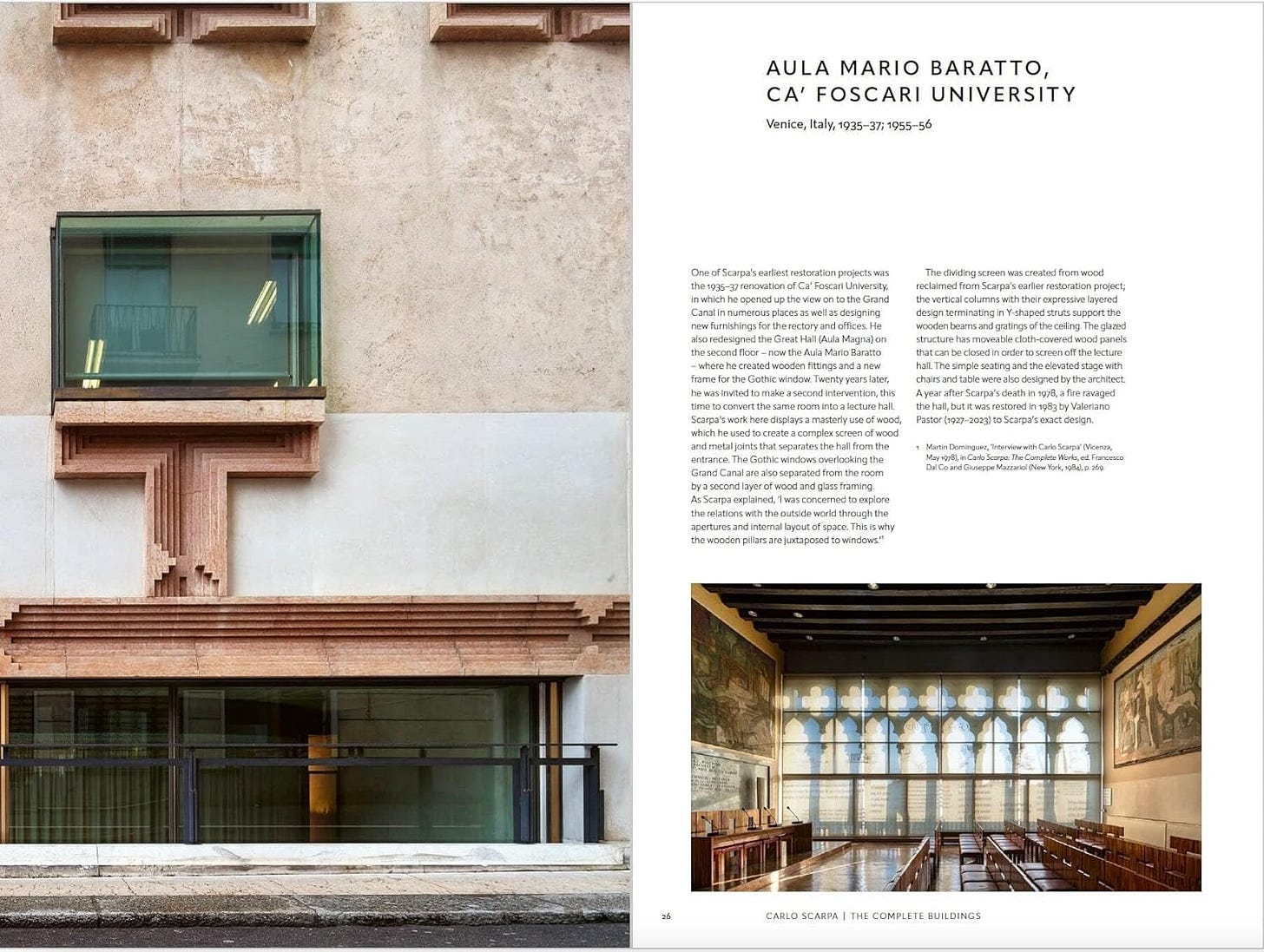

Carlo Scarpa: The Complete Buildings, with texts by Jale N. Ezren, edited and interviews by Emiliano Bugatti, and photography by Cemal Emden (Buy from Prestel / from Amazon / from Bookshop)

“Although not widely known during his lifetime,” the back cover of this book released last week contends, “over the past half-century Carlo Scarpa (1906–1978) has become one of the most revered of modern architects.” It is a hard statement to argue with, especially the latter half.

From the perspective of an architect, which I am, Scarpa’s buildings, landscapes, and interiors are a must when visiting his native Venice, and they are worthy of detours to other parts of Italy’s Veneto region. From the perspective of an author and editor, which I also am, books on Scarpa are coveted, with out-of-print titles often going for hundreds of dollars, much more than their original cover prices. Given the way Scarpa’s appeal has steadily increased since his passing, I’m surprised there aren’t more books made about his life and work. Of the books in English that I’m familiar with, recent titles have been updates to older books, in particular Carlo Scarpa and Castelvecchio Revisited, a 2017 expansion of a 1990 book by Richard Murphy, and Robert McCarter’s 2013 monograph on Scarpa that was released in a “classic format” in 2021.

Into this mix comes Carlo Scarpa: The Complete Buildings, which sees architect and photographer Cemal Emden visiting all of Scarpa’s (nearly) extant buildings, from those started in the 1930s to the ones completed by collaborators soon after his death in 1978. The completist nature of the undertaking — one that took three years to achieve — recalls Emden’s earlier Le Corbusier: The Complete Buildings and The Essential Louis Kahn (see the bottom of this newsletter for more information on the latter).

My first exposure to the architecture of Carlo Scarpa was in architecture school, specifically during a semester spent in Italy in 1995. The impression was strong and lasting, as I’m still enamored with Scarpa’s buildings and books about them. It helped that my classmates and I were able to visit a number of Scarpa projects in and beyond Venice, studied them in some depth, and probably “borrowed” one or two of his distinctive details in our studio projects that semester. The projects we visited were the ones Scarpa is best known for: the Museo di Castelvecchio and Banco Popolare in Verona; the Brion Cemetery near Treviso; and the Olivetti Showroom, Querini Stampalia, the base for the Monument to the Partisan Woman, and the entrance to the IUAV in Venice. We also visited the Gavini Showroom in Bologna, the lush interior that graces the cover of The Complete Buildings.

In the nearly 30 years since, I’ve only been able to see a few more Scarpa projects (all on the grounds of the Biennale’s Giardini, it turns out). This is all a way of pointing out that this completist is more than 40 works short of Emden’s feat: his lens captured 54 buildings, landscapes, interiors, and monuments designed by Scarpa — enough that on first read I found myself surprised at some of the more obscure projects on display in the book’s pages.

The Complete Buildings mainly consists of Cemal Emden’s lovely photographs, which occasionally linger on the details that Scarpa is known for but for the most part give broader views of facades, spaces, and surfaces. Most people who buy the book will do so just for the photographs and the comprehensiveness of them, but they are not alone. The book also features a lengthy essay by Jale N. Erzen, “Carlo Scarpa’s World: Beauty and Meaning,” as well as an interview with Carlo Capovilla, a fourth-generation owner of the carpentry workshop that Scarpa frequented during his whole career, an interview with Paolo Zanon and Francesco Zanon, blacksmiths who worked with Scarpa for more than two decades, and a timeline of Scarpa’s life and work.

The interviews are particularly interesting, given the way Scarpa worked: instead of producing working drawings (Scarpa was not a licensed architect but collaborated with architects who would, I presume, do those required drawings), he would draw sketches on site for the builders to follow. So Capovilla, who did not know Scarpa but has restored a number of his projects, illuminates how certain details were discovered via disassembly — necessary since drawings of the assemblies did not exist — while the Zanons, who did know Scarpa in his lifetime, take immense pride in the work they did with him but also lament the wider loss of the skills and patronage needed to restore and care for such highly detailed, idiosyncratic creations.

The discoveries necessary for the restorations mentioned in the interviews find parallels in Scarpa’s work itself, particularly Castelvecchio, Querini Stampalia, and the numerous other renovations he undertook. “As in several of Scarpa’s restoration projects, the architect had to rediscover and restore the building's original state,” Ezren writes about Querini Stampalia in the book, “in this case seriously distorted and concealed by previous interventions.” Such a statement amplifies just how many of Scarpa's projects were restorations, but also, more importantly, the high levels of respect he gave existing buildings. A similar respect for Scarpa’s works can be found in Emden’s beautifully attentive photos.

Books Released This Week (and Last Week):

(In the United States, a curated list)

American Modern: Architecture; Community; Columbus, Indiana by Matt Shaw, photographs by Iwan Baan (Buy from The Monacelli Press / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — The Midwestern modernist mecca that is Columbus, Indiana, has been the subject of quite a few books (Balthazar Korab’s photo book on the town is a favorite of mine), but it has not been given an overarching history until now, with this heavily illustrated paperback by a writer who is also a Columbus native.

BR Design: people who listen. interiors that work. by Roger Yee (Buy from Visual Profile Books / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — This is the first monograph on BR Design, the interior design firm that was founded in New York City in 1985 and whose projects include the headquarters of Assouline and the offices of Cooper Robertson.

Hélène Binet by Marco Iuliano and Martino Stierli (Buy from Lund Humphries / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — The first book in the “Architectural Photographers” series from Lund Humphries is devoted to Hélène Binet, who is most famous for capturing buildings by Zaha Hadid and Peter Zumthor. It features essays by series editor Marco Iuliano and MoMA curator Martino Stierli, followed by a catalog of more than 170 photographs, some published for the first time.

Into the Quiet and the Light: Water, Life, and Land Loss in South Louisiana by Virginia Hanusik (Buy from Columbia University / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — Photographs by Virginia Hanusik of an area hit by the double whammy of climate change and the fallout of the fossil fuel industry are accompanied by texts by scholars, artists, activists, and practitioners working in the region.

Le Corbusier by Kenneth Frampton (Buy from Thames & Hudson / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — This revised and updated edition of Kenneth Frampton's book on Le Corbusier in Thames & Hudson's "World of Art" series includes a new introduction and color illustrations. (The first edition was published in 2001, a year ahead of yet another book by Frampton on Le Corbusier: a coffee table book with specially commissioned photos by Roberto Schezen.)

Vienna: The End of Housing (As a Typology) edited by Anh-Linh Ngo, Bernadette Krejs, Christina Lenart and Michael Obrist (Buy from ARCH+/Spector Books / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — The German architecture magazine ARCH+ makes just one of its four issues each year available in an English translation and this year’s is devoted to the current state of housing in Vienna.

Full disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, AbeBooks Affiliate, and Bookshop.org Affiliate, I earn commissions from qualifying purchases made via any relevant links above and below.

Book News:

Michael J. Crosbie reviews Paul Kidder's Minoru Yamasaki and the Fragility of Architecture (Routledge) for Common Edge.

Doug Spencer reviews Sérgio Ferro's Architecture from Below: An Anthology (MACK) for The Architect's Newspaper.

Mrinmayee Bhoot reviews Markus Miessen's Agonistic Assemblies: On the Spatial Politics of Horizontality for STIR.

I rounded up 12 Summer Reads for World-Architects.

Publishers Weekly has an obituary on publisher David A. Morton, who oversaw architecture titles at Rizzoli for nearly 30 years.

From the Archives:

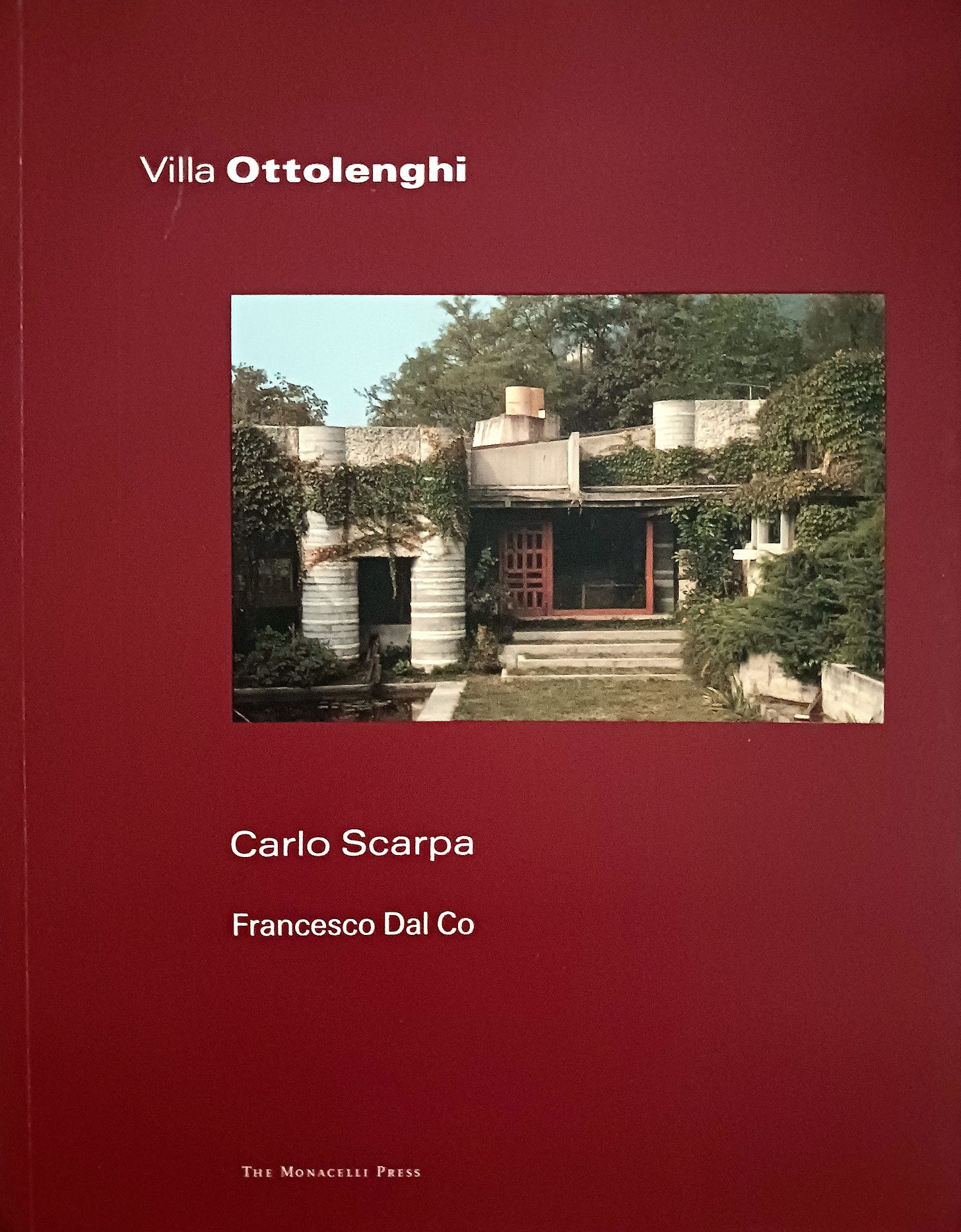

In the early days of my first blog, A Weekly Dose of Architecture, I featured Carlo Scarpa's Villa Ottolenghi in Lake Garda, Italy. I knew a good deal about Scarpa from my semester in Italy, but I knew nothing about this villa until I came across Francesco Dal Co's Villa Ottolenghi: Carlo Scarpa, published by The Monacelli Press in 1997. Given that I started my blog in early 1999, when there was very little architecture content online, many of my early “doses” started with books, such as this one, that I would scan — literally and figuratively — for photos and ideas. This book fitted into Monacelli's “One House” series, which also included Richard Meier's Ackerberg House and Addition, Steven Holl's Stretto House, Antoine Predock's Turtle Creek Residence, and Mark Mack's Stremmel House.

The villa was one of Scarpa's last projects, so Dal Co compares it to the Brion Cemetery, another project that Scarpa worked on until his death in 1978. Even with an apparent influence from that more famous project, the villa has its own distinct character, much of it coming from the structural system that he employed and expressed in his idiosyncratic way, as heavy, round, striated concrete columns. In addition to Dal Co's text, the book has plenty of photos, plans, and no shortage of Scarpa's beautiful detail sketches.

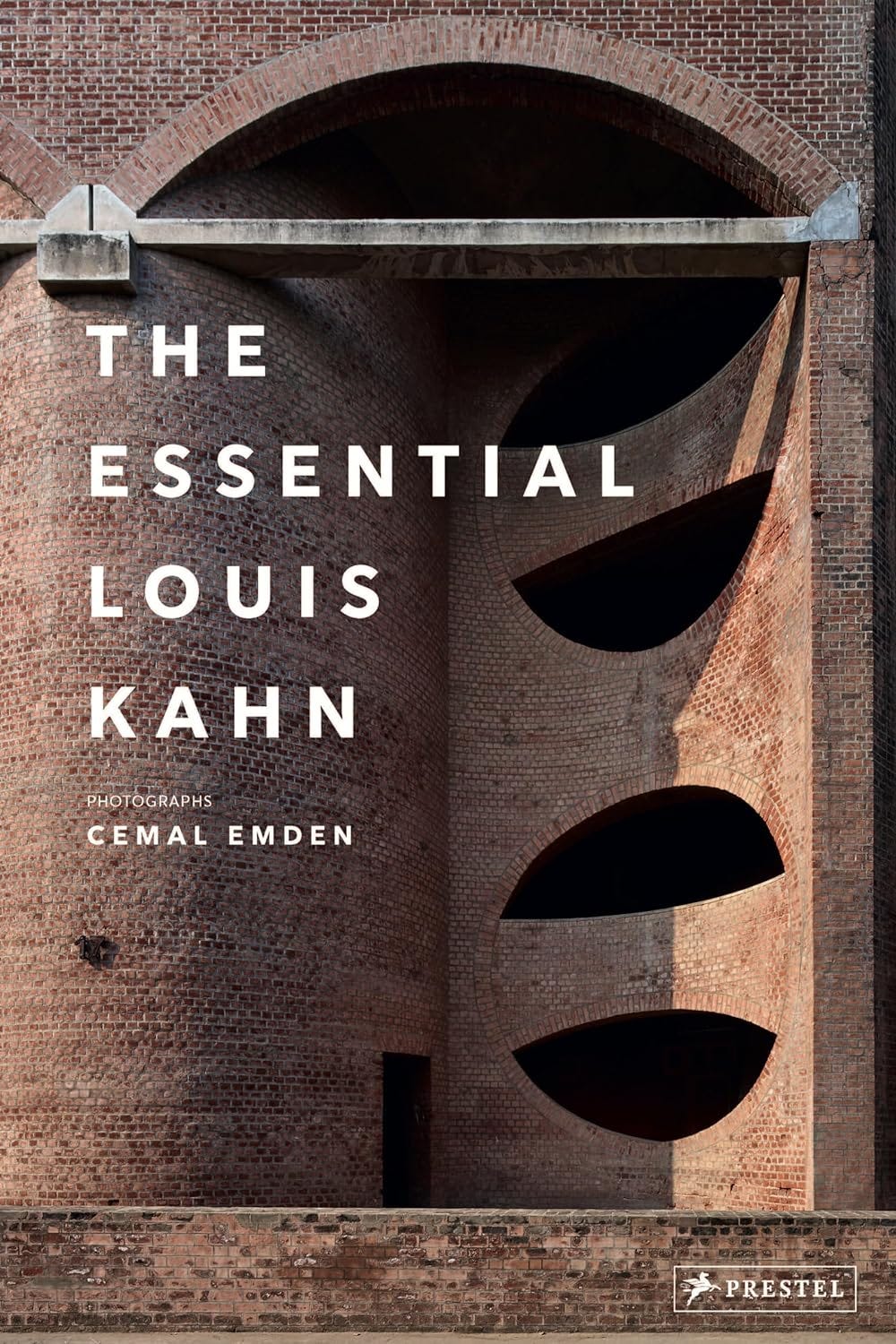

Before his book on Scarpa, photographer Cemal Emden released with Prestel two books on two even more famous architects: Le Corbusier: The Complete Buildings (2017) and The Essential Louis Kahn (2021). The first, like the Scarpa book, aims for completeness, via the documentation of 52 extant buildings by Le Corbusier, while the Kahn book focuses on his “essential” buildings, what Jale N. Ezran describes in the introductory essay as “the mature period of Kahn’s active career,” from 1951 to 1974. This postwar period comprises just over twenty works, less than half of the number in each of the Corbusier and Scarpa books, meaning Emden could explore the buildings in more depth. With large-scale projects such as the Indian Institute of Management and the National Assembly in Dhaka, as well as such masterpieces as the Salk, the Kimbell, Exeter Library, and the YCBA, numerous photographs are required to fully capture the spaces, materials, and character of Kahn’s buildings. That said, I’m surprised not to see Emden providing the “money shot” of the Salk’s plaza and fountain leading to the Pacific; instead, we see an off-center shot akin to the one in Re/Framing Louis Kahn, the 2017 exhibition that presented Emden’s photos alongside Kahn’s drawings.

Like the Scarpa book, The Essential Louis Kahn features contributions beyond Emden’s photographs. There are Ezran’s essay mentioned above, project descriptions by Caroline Maniaque accompanying the photos, and, in the back matter, a short essay and career-spanning chronology, both by Ayşe Zekiye Abali. These are valuable additions to Emden’s photographs, but unfortunately readers are not given biographical information on these contributors — a slight omission that was remedied in Emden’s later books featuring photographs of buildings by famous architects.

Thank you for subscribing to A Weekly Dose of Architecture Books. If you have any comments or questions, or if you have your own book that you want to see in this newsletter, please respond to this email, or comment below if you’re reading this online. All content is freely available, but paid subscriptions that enable this newsletter to continue are welcome — thank you!

— John Hill