Architecture Books – Week 3/2025

Gimme an I! Gimme an A! Gimme a U! Gimme an S! What's that spell?

The “Book of the Week” in this newsletter for the week of January 13 is Building Institution, Kim Förster’s in-depth history of the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies (IAUS), which was formed by Peter Eisenman in 1967 and is best remembered for Oppositions and other publications. IAUS is appropriately the subject of the “From the Archive” book at the bottom of the newsletter, while in between are the usual headlines and new releases. Happy reading!

Book of the Week:

Building Institution: The Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies, New York 1967-1985 by Kim Förster (Buy from Columbia University Press / Download open-access PDF from transcript publishing / Buy from Amazon / Buy from Bookshop)

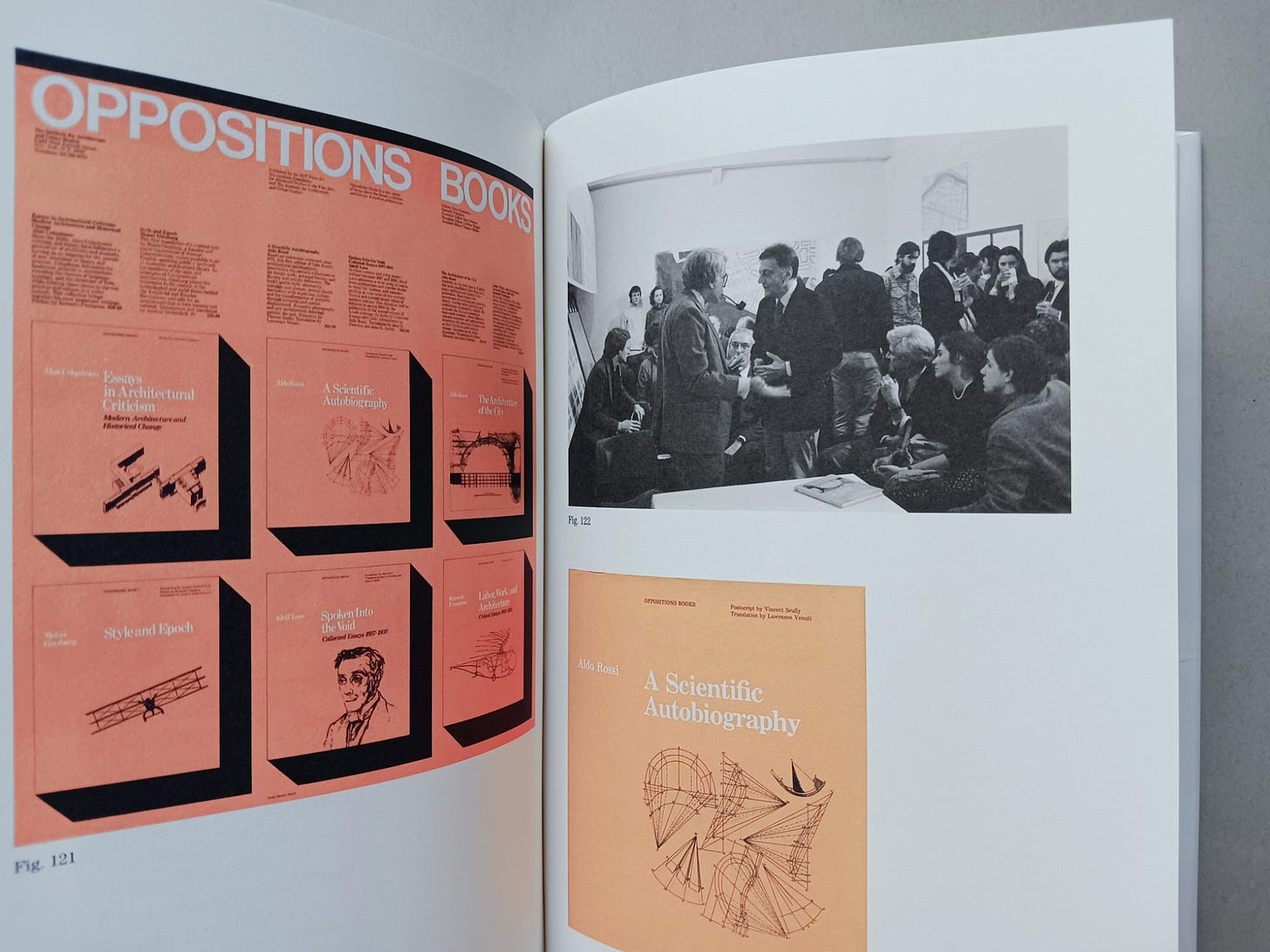

Thirty years ago, when I spent a semester in Italy during my fourth year of architecture school, a “textbook” in one of my classes was Aldo Rossi’s meandering and clearly personal A Scientific Autobiography. We read and discussed it in a seminar, often holding our classes in a piazza adjacent to the study center — a fitting setting for reading about an architect who valued memory and the historical morphology of cities. At the time I didn’t think at all about how the book, with its bold yellow cover and square format, fit alongside the other books bearing the “Opposition Books” names, or the similarly formatted journal Oppositions, which I don’t recall having seen, much less read, in those years. After I graduated from architecture school and my personal library grew, I realized that Oppositions and Opposition Books were the most influential and lasting documents of the Institute of Architecture and Urban Studies (IAUS), which was founded by architect Peter Eisenman in 1967 and lasted until either 1984 or 1985, depending on one’s source. But in those nearly twenty years, the IAUS did much more than produce a journal and books focused squarely on history and theory. Eisenman and company designed and realized a building in Brooklyn; held classes, lectures, and exhibitions at their Bryant Park location; and published a monthly newspaper. This sometimes sequential, often overlapping output is painstakingly documented and described by Kim Förster in Building Institution, a 584-page tome developed from his 2011 doctoral thesis at ETH Zürich, and released by Transcript in the US last fall. For someone like me, whose interests in architecture extend to how the discipline is shaped by publications, institutions, and the like, Building Institution is a fascinating and illuminating read that had me reconsidering every position I previously held about the IAUS.

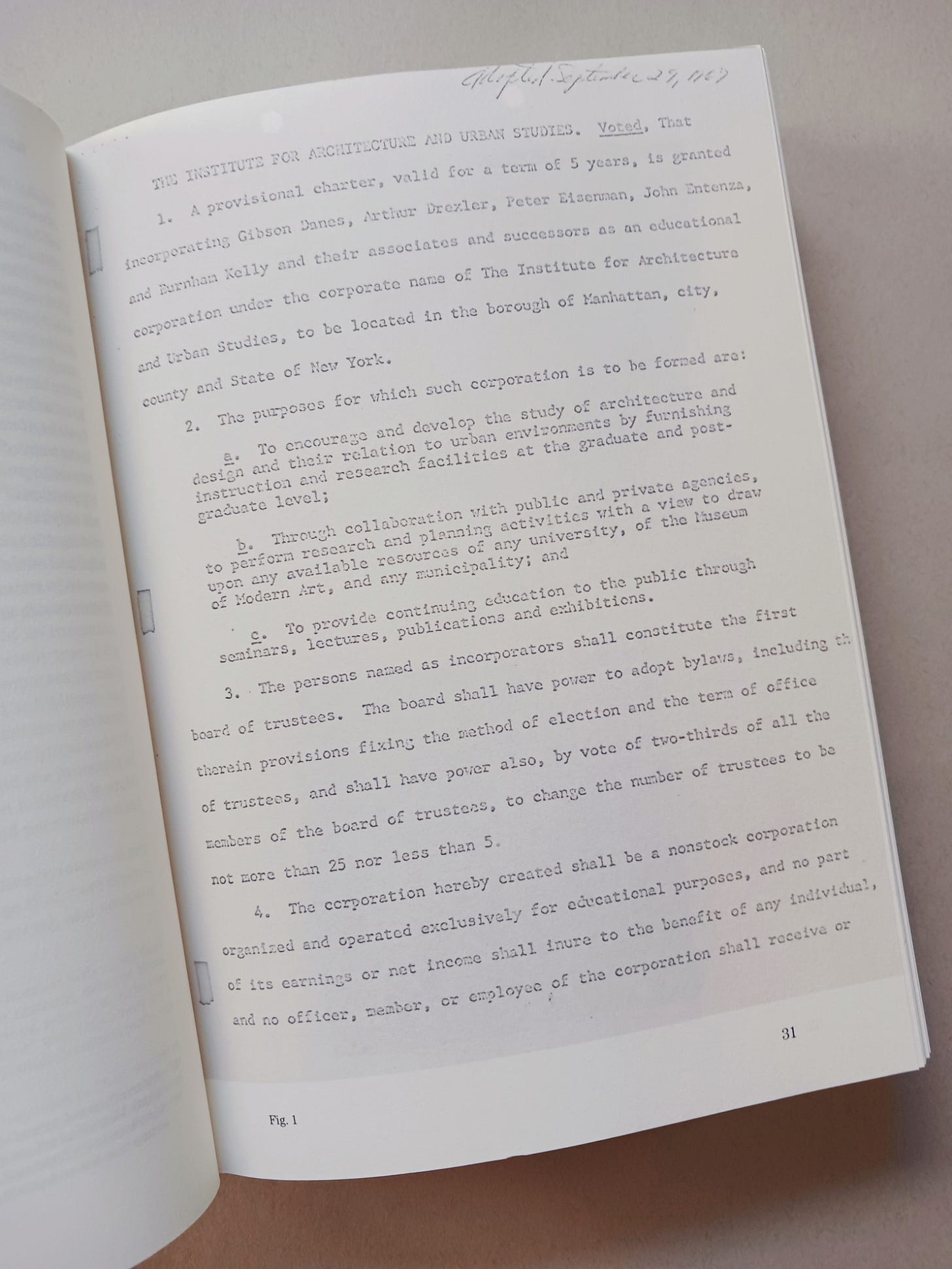

While Oppositions can safely be described as the Institute’s flagship production, it was not launched until 1973, six years after the IAUS was formally created; likewise, Opposition Books did not see the release of what would ultimately be just five books until 1982, a few years before the Institute dissolved. In other words, the IAUS was not solely or always about shaping architectural education and culture via publications of history and theory, something it became best known for. When it was founded in 1967, the by-laws approved by trustees laid out three objectives: “furnishing instruction and research facilities at the graduate and postgraduate level,” “perform research and planning activities” through collaborations with public and private agencies, and “provide continuing education to the public through seminars, lectures, publications and exhibitions.” Publications are there, but they are one element alongside numerous others. Ultimately the Institute would do all it said it would do in the 1967 by-laws, but in its early years — before Richard Nixon reshaped federal housing policy ca. 1973 and before New York City’s fiscal crisis in 1975 — it was able to work as a consultant on urban and architectural projects commissioned by city, state, and federal authorities. Most famous among them are the low-rise housing proposals in Brooklyn and Staten Island, commissioned by the New York State Urban Development Corporation and done with the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA, who exhibited the proposals in 1973). Kenneth Frampton, an Institute Fellow, worked on the design of the project in Brownsville, Brooklyn, while Eisenman was in charge of the one in Staten Island. Only the Marcus Garvey project in Brownsville would be realized (completed in 1976), notably becoming the Institute’s only architectural work, thanks to political and economic circumstances but also the Institute’s related shift toward teaching.

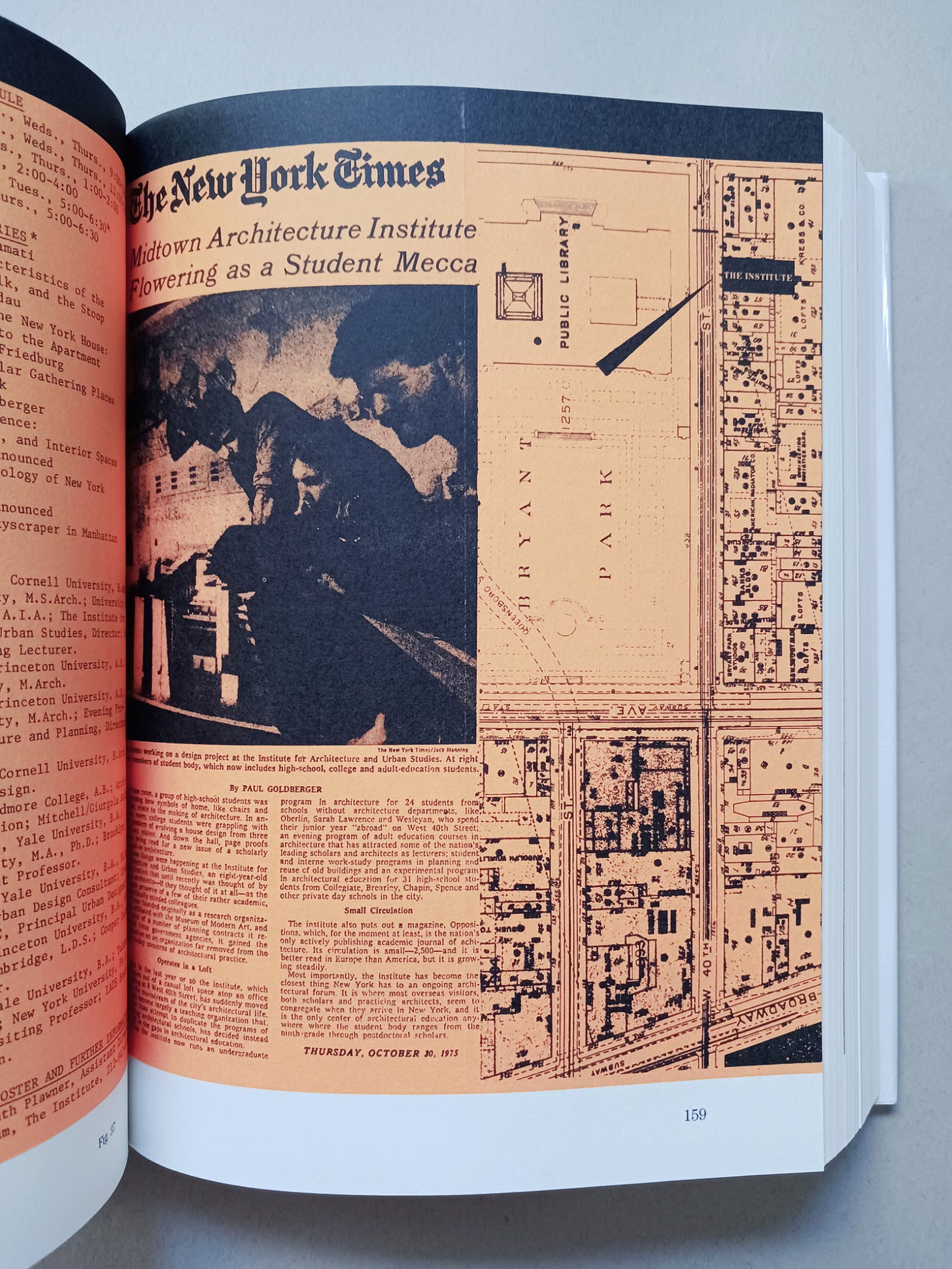

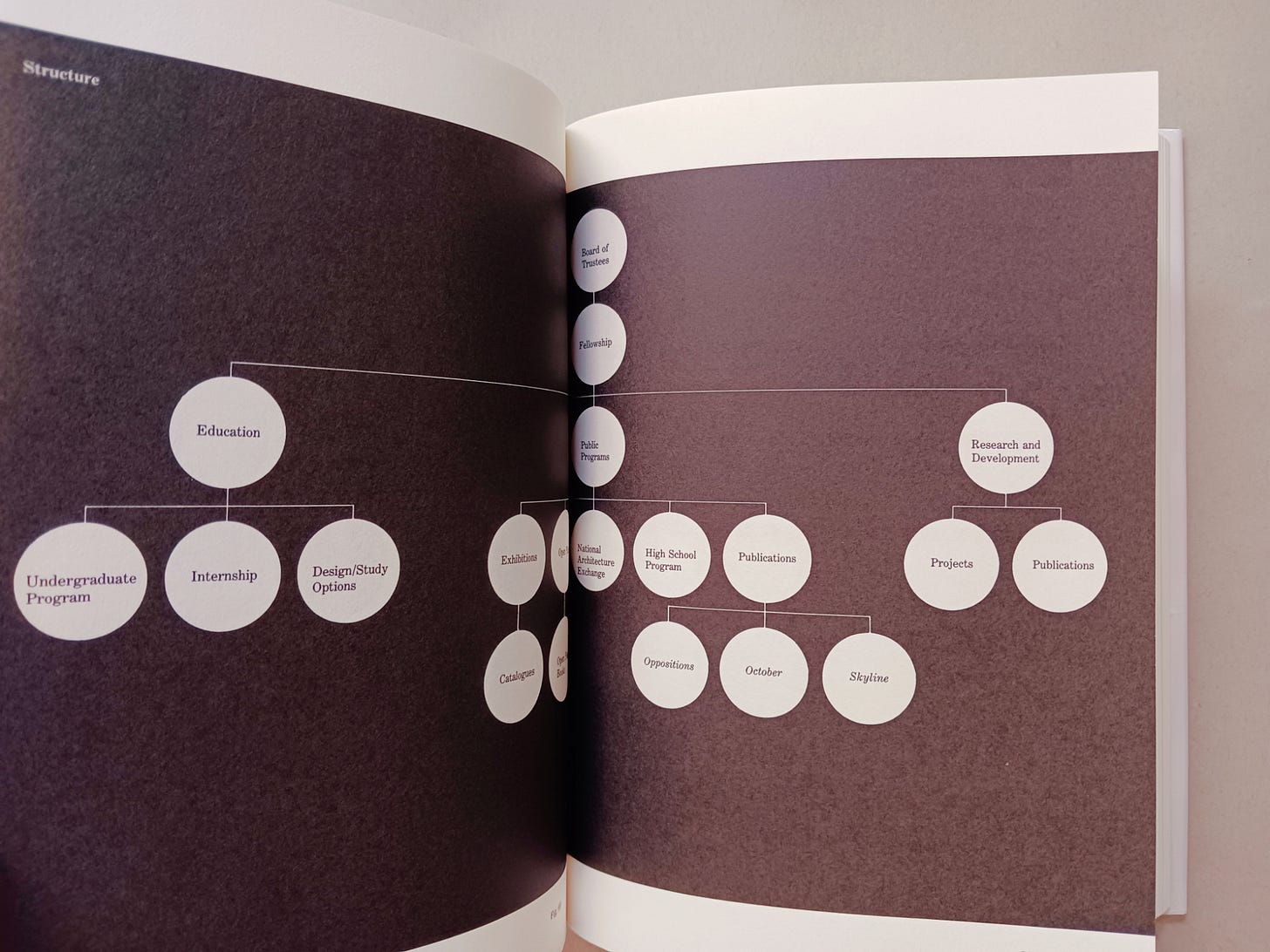

Förster discusses Marcus Garvey and other projects in “Project Office,” the first of four sizable thematic and roughly chronological chapters in the book. It is followed by “Architecture School,” which picks up in the mid-1970s and the formal introduction of educational programs at the IAUS’s home on East 40th Street. Although the Institute offered “education” in its early years, it was basically the equivalent of interns working on the Institute’s architecture and urban commissions. Förster describes the Institute’s mid-70s reinvention as an albeit non-accredited architecture school as “unavoidable,” given that the potential for public-sector work disappeared and secondary education was blossoming nationwide with a shift from industry to the service sector. Förster further describes the Undergraduate Program in Architecture launched by the IAUS in 1974 as “a truly innovative and comprehensive education offering” that had not existed before in the USA. Eisenman and his colleagues offered students in liberal arts schools without architecture programs the chance to spend their junior year at the Institute, rather than at a program in Europe, as in my more typical experience two decades later.

The Institute had other educational offerings, including an equally innovative High School Program, but they were overshadowed by an intense schedule of cultural offerings that catered to architects as well as non-architects. These took the form of evening lectures, Saturday seminars, and exhibitions, among other things described in the third chapter, “Cultural Space.” In its heyday in the mid-to-late-70s, something was taking place every single day of the week at the Institute, making it a hub of activity akin to today’s equivalent, the Center for Architecture in Greenwich Village. Although Förster’s book focuses on the Institute’s finances and internal bureaucracy throughout the book, this chapter accentuates those characteristics while also bringing Eisenman’s ability to network and promote himself to the fore, and revealing how the Institute adapted itself to changing social, political, and economic contexts, yet without ever critiquing or commenting on them. Although the IAUS has been remembered as an alternative, almost avant-garde space for architecture, particularly in its embrace of modernism over then burgeoning postmodern architecture, it was very much entrenched in the status quo, especially when it came to gender, race, and money.

The fourth and longest chapter in Building Institution is “Publishing Imprint,” which describes over roughly 120 pages (a book in and of itself!) the various printed output of the IAUS: Oppositions, the journal that saw 26 issues published between 1973 and 1984 (William Stout Architecture Books has a handy listing of them); Opposition Books (1982–1984), which included two books by Aldo Rossi, a collection of essays by Adolf Loos and another by Alan Colquhoun, and the translation of a 1924 book by Moisei Ginzburg; the IAUS Exhibition Catalogs (1978–1982), which oddly outnumbered the exhibitions themselves and were rarely released at the same time of the exhibitions or in the order they happened; and Skyline, the monthly newspaper edited first by Andrew MacNair and then Suzanne Stephens, offering a mix of reviews, interviews, gossip, a monthly calendar, and other fare considerably “lighter” and more accessible than Oppositions (the issues edited by Stephens are available as PDFs at US Modernist). For fans of books about books, like myself, this chapter is a gem. Förster describes their contents a little bit, most memorably calling the “philosophically and ideologically deliberative texts” in Oppositions “almost incomprehensible,” but most of his words are given over to how the publications were developed, designed, paid for, and published. This makes sense because, after all, Building Institution is a book about an institution, about how it functioned day to day, how its mission evolved over the years, and how the people involved got along (or didn’t). Publications were a large part of the IAUS — “a complex entity,” in Förster’s words — and they are the most lasting part of its legacy.

With its four lengthy chapters, Building Institution adopts a logical structure, prefacing each chapter with visual essays that leave each chapter as pages of text and footnotes free of images. The visual essays mainly feature documents and photographs pulled from the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies fonds at the Canadian Centre for Architecture, where Förster did much of his research, and the Vignelli Archives at RIT’s Vignelli Center for Design Studies, necessary given the importance of Massimo Vignelli in designing the Institute’s publications but also shaping its visual branding. This alternating image/text structure works well for the most part, though I wish the images in the visual essays were referenced in the text, and I wish captions for the images were not relegated to the back matter, thereby necessitating some flipping back and forth, something you don’t have, for instance, with the footnotes. My other quibbles in the book are minor, including Förster’s apparent desire to say many things in long, meandering sentences, which is common for academics but thankfully does not approach the incomprehensibility of Oppositions. Also, I made note of just a few errors as I read Building Institution (St. Louis is in Missouri, not Michigan; Frederieke Taylor was a she, not a he; and if Oppositions won anything from the AIA in 1982, it was an honor award, not its gold medal), but they are minuscule in a nearly 600-page book that filters reams of writings, historical documents, and oral histories, and are basically nothing compared to other academic books I’ve read. Ultimately, the book is a valuable document giving the fullest story of an important and influential institution spanning architecture’s transition toward postmodernism.

Books Released This Week:

(In the United States, a curated list)

The Anatomy of the Architectural Book by Andre Tavares (Buy from Lars Müller Publishers / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Dissecting a breadth of architectural books through five conceptual tools—texture, surface, rhythm, structure and scale—author and architect André Tavares analyzes the material quality of books in order to assess their dialogue with architectural knowledge at large.” Now in paperback.

Window Shopping with Helen Keller by David Serlin (Buy from University of Chicago Press / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “A particular history of how encounters between architects and people with disabilities transformed modern culture.”

Zaha Hadid's Paintings: Imagining Architecture by Desley Luscombe (Buy from Lund Humphries / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Zaha Hadid is widely regarded as a visionary and influential architect, who became globally acclaimed by the time of her untimely death in 2016. This book is the first to focus on how painting was fundamental to her practice.”

Contemporary Michigan: Iconic Houses at the Epicenter of Modernism by Peter Forguson (Buy from Visual Profile Books / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Residents of Detroit, and indeed the entire state of Michigan, have been living with some of the finest work by such Modern masters as Frank Lloyd Wright, Mies van der Rohe, and Eliel Saarinen since the dawn of the 20th century.” This book documents more than 70 of them.

Mass Housing in Ukraine: Building Typologies and Catalogue of Series 1922–2022 by Kateryna Malaia and Philipp Meuser (Buy from DOM Publishers / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “The all-out war in Ukraine, started by the Russian Federation in 2022 has disproportionally affected housing and residential infrastructure. […] With the scale of damage and loss in mind, and the future wide-ranging reconstruction that will inevitably take place after the war, this study examines the history and typologies of mass housing in Ukraine.”

Full disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, AbeBooks Affiliate, and Bookshop.org Affiliate, I earn commissions from qualifying purchases made via any relevant links above and below.

Book News:

“The Year of Meh,” in which critics Mark Lamster, Alexandra Lange, Carolina A. Miranda dole out their annual Architecture and Design Awards. Of particular relevance to this newsletter is the “X-Acto of Doom” going to Thom Mayne and L.A.’s A+D Museum for Of the Moment, “a design publication that gives air to single family houses and oodles of form-making. Instead of articles, you’ll find ‘conversations,’ because pesky critics have a habit of getting in the way.” The trio provided a helpful link to a scan of the broadsheet.

“Walking New York City with Owen Hatherley”: Lynnette Widder reviews Hatherley’s Walking the Streets, Walking the Projects (Repeater Books, 2024) at World-Architects. (Full disclosure: I edited this review as part of my editorial work at W-A.)

Country Life editor John Goodall assembles “a shortlist of his favorite architecture books published recently,” with titles on British and/or traditional/classical architecture.

Read a review of Beyond the Envelope: Twenty-one Pioneering Architectural Projects from the Early Twenty-first Century, Twenty-one Interviews with Their Architects (Oscar Riera Ojeda Architects, 2024), edited by NYIT professor Tom Verebes, at Architectural Record.

From the Archives:

Before the publication of Kim Förster’s Building Institution last fall, the two histories of the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies (IAUS) were personal, not academic: The Making of an Avant-Garde: The Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies 1967-1984, the 2013 documentary directed by architect, professor, and longtime IAUS Fellow Diana Agrest; and IAUS: An Insider's Memoir, “a combined memoir and impressionistic history” self-published in 2010 by Suzanne Frank, who was a librarian and Fellow at the Institute but is more familiar as Peter Eisenman’s client on House VI (she even wrote a book about the house). I watched the first as part of an online event in November 2020, in which Kim Förster was in attendance; I shortly thereafter bought the second (if you want the book, be sure to buy it via the link above, not Amazon, where it goes for twice as much); then I wrote about Frank’s book on my blog in early 2021. Here is how I matter-of-factly described the book:

“IAUS: An Insider's Memoir uses the output of the Institute to structure its seven chapters. Following the first chapter, which breezes through IAUS's chronological history, are individual chapters on its ‘urban aspirations,’ which took the form of Marcus Garvey Village and the On Streets book [by Stanford Anderson]; on Oppositions, the intellectual journal that was published from 1973 to 1984 and whose selected essays were published in Oppositions Reader in 1999; on its educational and public programs; on the Skyline newsletter that was spearheaded by Andrew MacNair and then edited by Suzanne Stephens in its second iteration; and on the exhibitions and their occasional printed catalogs. Following a concluding chapter, ‘The IAUS and the Dialectic,’ are three appendices: the 27 interviews, floor plans of the two-story IAUS space on the top of 8 West 40th Street, and Frederieke Taylor's academic paper from 1990 on the exhibitions held at the Institute. The interviews start on page 202, meaning Frank's text is considerably shorter than the book's 364 pages; combined with the fact the line spacing is 1.5 for everything but the appendices, the ‘insider's memoir’ is a fairly quick read, particularly for those interested in IAUS. Unfortunately, the book is in need of both a good editor and a graphic designer, given the occasional grammatical errors and the fractured nature of the writing, and how much the page layout looks like an academic manuscript rather than a book. Interested readers who can set aside these distractions will find much to learn in this most comprehensive account on IAUS — until Förster delivers on his monograph that ‘challenges the predominant myth of the Institute as a think tank.’”

Thank you for subscribing to A Weekly Dose of Architecture Books. If you have any comments or questions, or if you have your own book that you want to see in this newsletter, please respond to this email, or comment below if you’re reading this online. All content is freely available, but paid subscriptions that enable this newsletter to continue are welcome — thank you!

— John Hill