This newsletter for the week of heads east, looking at a new book on modern Chinese architecture and delving into the archive to find an old book on traditional Chinese architecture. In between are the usual new releases and headlines. Happy reading!

Book of the Week:

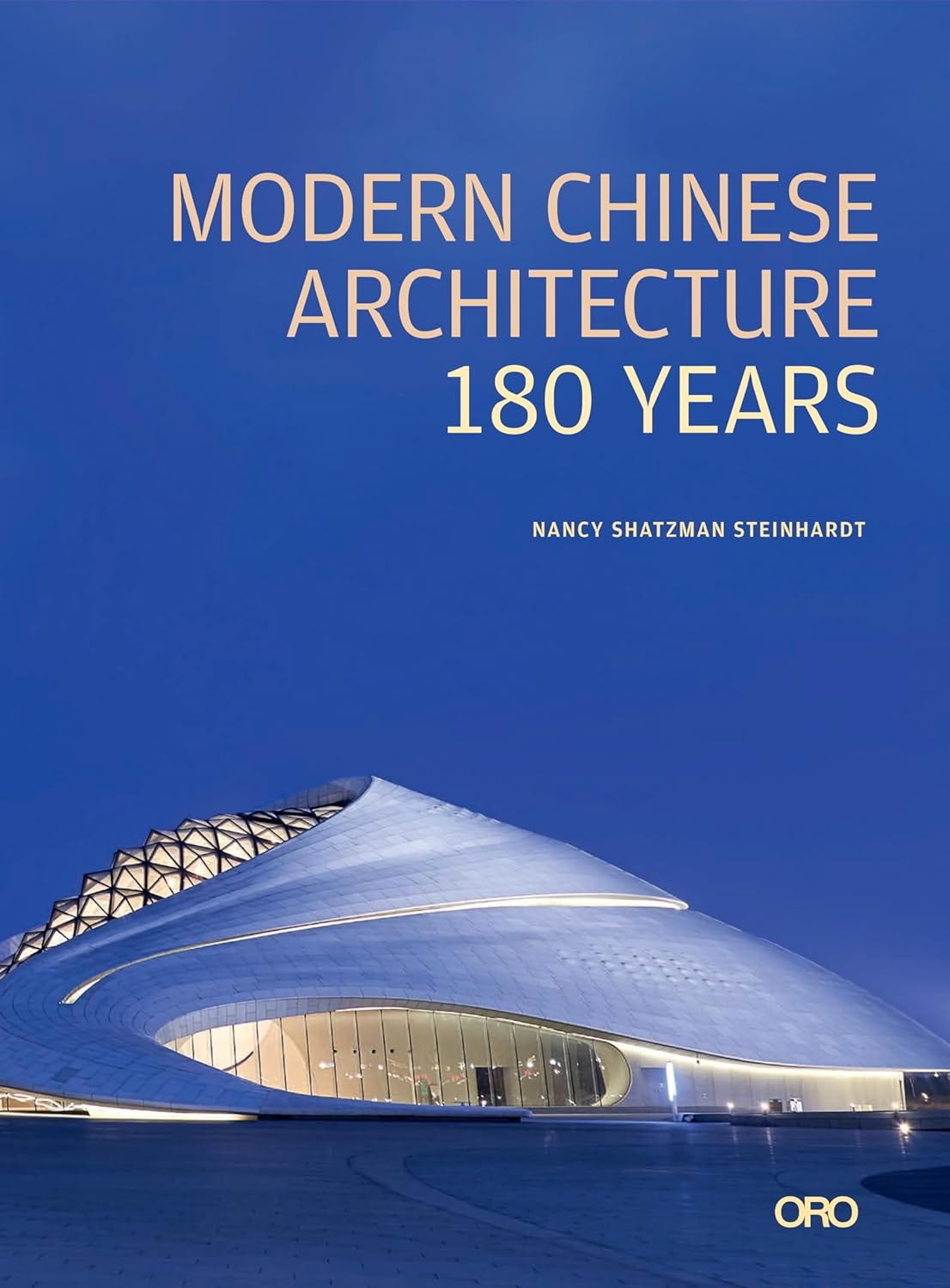

Modern Chinese Architecture: 180 Years by Nancy Shatzman Steinhardt (Buy from ORO Editions / from Amazon / from Bookshop)

Exactly twenty years ago, Rem Koolhaas and company implored readers to “Go East” in the pages of Content, the 2004 followup to the hugely influential 1996 monograph S,M,L,XL. As I wrote on my blog at the time, “This [easterly] movement sums up the present situation for OMA (and its offshoot AMO) as it eyes the enormous potential in China and the burgeoning urbanism of much of Asia.” The most famous output of their geographical shift was the CCTV Headquarters, the boldly cantilevered, looping skyscraper that OMA started working on in 2002 and which wrapped up construction ten years later. Not surprisingly, CCTV is one of the 218 (by my count) projects included in Nancy S. Steinhardt’s sweeping yet brisk survey of 180 years of modern architecture in China, released this week by ORO Editions.

CCTV is appropriately found in the book’s final chapter, “Dangdangdai, 2000–Present: Contemporary Global Architecture,” coming after five other chronological chapters that cover anywhere from 12 to 72 years. The book has a consistent format, in which each project is documented across one spread, with typically just two or three photographs and a brief description. The spread for CCTV has two exterior photographs (one full-page, one small), a 70-word description with the barest of facts — Koolhaas designed it; it is 51 stories and 234 meters tall; a fire delayed its opening to 2013; it’s nicknamed “Big Pants”; and “six horizontal and six vertical strips” [?] yield 473,000 m2 of floor space — and a generous amount of white space. Very little is learned on these two pages, so the inclusion of the building among the 217-or-so other buildings must be the point. Or to skew an idiom: the forest is more important than the individual trees.

I’ll admit my knowledge of Chinese architecture, be it historical or modern, is rather incomplete. In regards to buildings this century, which occupies my time more than other eras, my personal tastes are more aligned with the likes of Wang Shu and Lu Wenyu’s Amateur Architecture Studio, whose buildings are more strongly rooted in the country’s past, than with modern intrusions like CCTV. (That said, OMA’s CCTV and Amateur Architecture Studio’s Xiangshan Campus of the China Academy of Art are two of the hundred buildings in my 100 Years, 100 Buildings.) But I would have a hard time telling anyone about Chinese architecture in the middle of the 20th century, much less the 19th. As such, I had been looking forward to Modern Chinese Architecture: 180 Years since I learned about it many months ago. I did not know what to expect exactly, but I knew that Steinhardt, Professor of East Asian Art and Curator of Chinese Art at the University of Pennsylvania, has written and edited numerous books on Chinese architecture, including The Borders of Chinese Architecture (Harvard University Press, 2022), Chinese Architecture: A History (Princeton University Press, 2019), and Chinese Architecture (Yale University Press, 2002).

Unlike the scholarly nature of these and other books bearing her name, Modern Chinese Architecture is academic in two other senses: it is aimed at students of architecture and seems to have been produced primarily by the same. Steinhardt admits some of this in the preface, indicating that “use in the university classroom was central,” her research for the book yielded “nearly 500 buildings worthy of further investigation,” and the selection was narrowed down via a seminar held at Penn in the fall 2021 semester with a handful of grad students. Their choices were “driven by history, the confirmed or anticipated importance of the structure or its architect, unique or highly unusual features, and always by strong visual impact.” The result is a sizable, chronological photo book that starts with the end of the First Opium War (1842) and ends near the present day, exactly 180 years later.

Brevity is key in Modern Chinese Architecture: In addition to the one-building-per-spread format, the six chapter introductions are short, broken down into decade-by-decade descriptions that give historical context to the buildings that follow. The aforementioned project descriptions range from maybe ten lines of text, as in CCTV, to two or three paragraphs at the most. This is publishing for the digitally distracted: concise in content, comprehensive in coverage, and visually appealing. I’m impressed by the quality and diversity of the roughly 200 buildings in the book, and I liked seeing the evolution of modern Chinese architecture across nearly 200 years on my first flip through the book. That is ultimately what this book is: a book for browsing, not a reference to be consulted. This is unfortunate, as I think it easily could have been the latter as well.

At the start of this review I noted that, “by my count,” there are 218 projects in Modern Chinese Architecture. This count had to be done manually, in my case using the image credits at the back of the book, because the projects are not listed in the table of contents (just the introduction and six chronological chapters), nor are they located on the map on page 7 or listed in the index — because there is no index. So if you want to find a particular project by a particular architect, you have to flip through the book, though this search is easier if you know when the building was completed. Do you want to find buildings in Beijing? Start flipping. Did you look through the book once and now you want to go back to find a specific building? Start flipping. Are you curious if there are multiple buildings in the book designed by Amateur Architecture Studio? You know what to do.

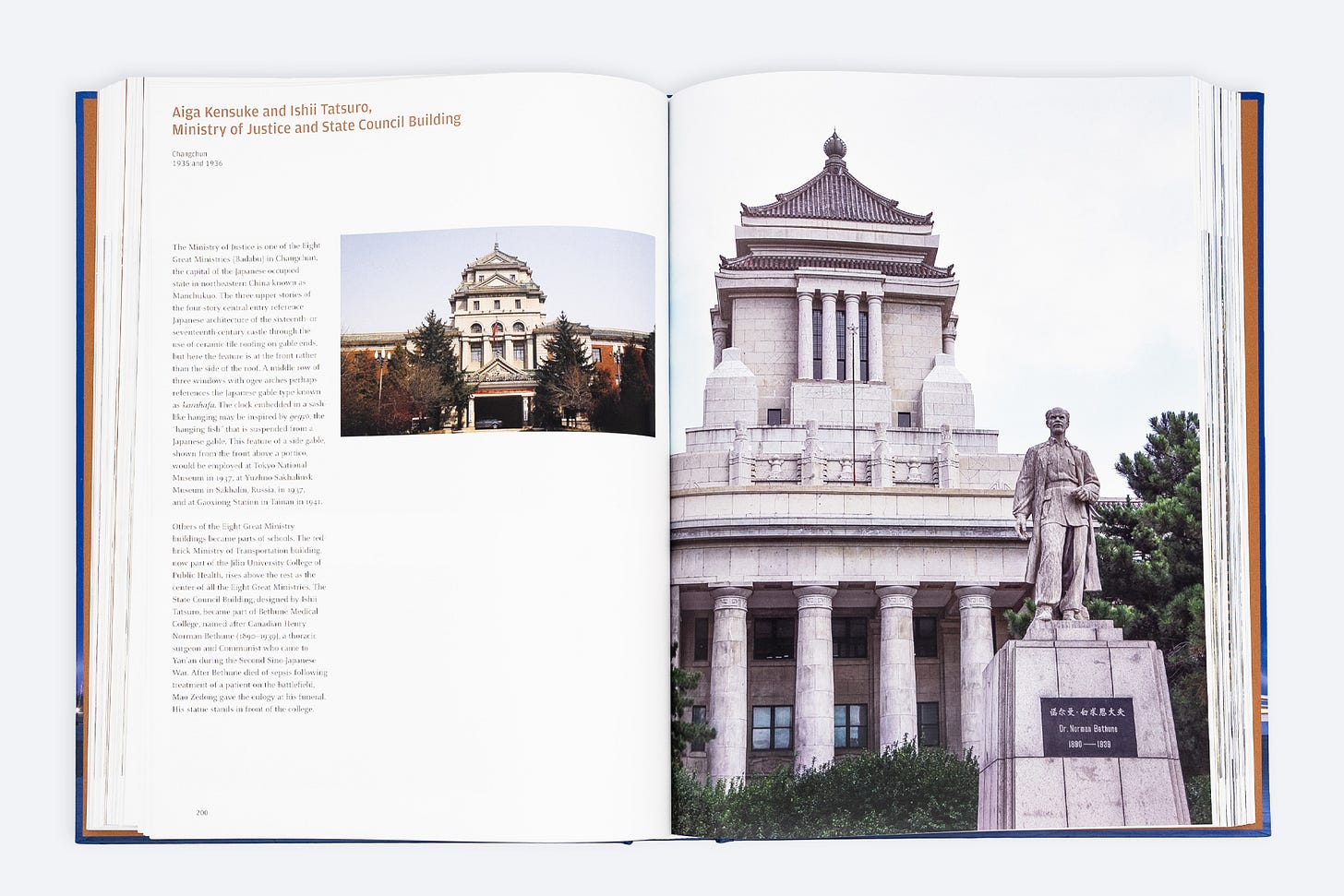

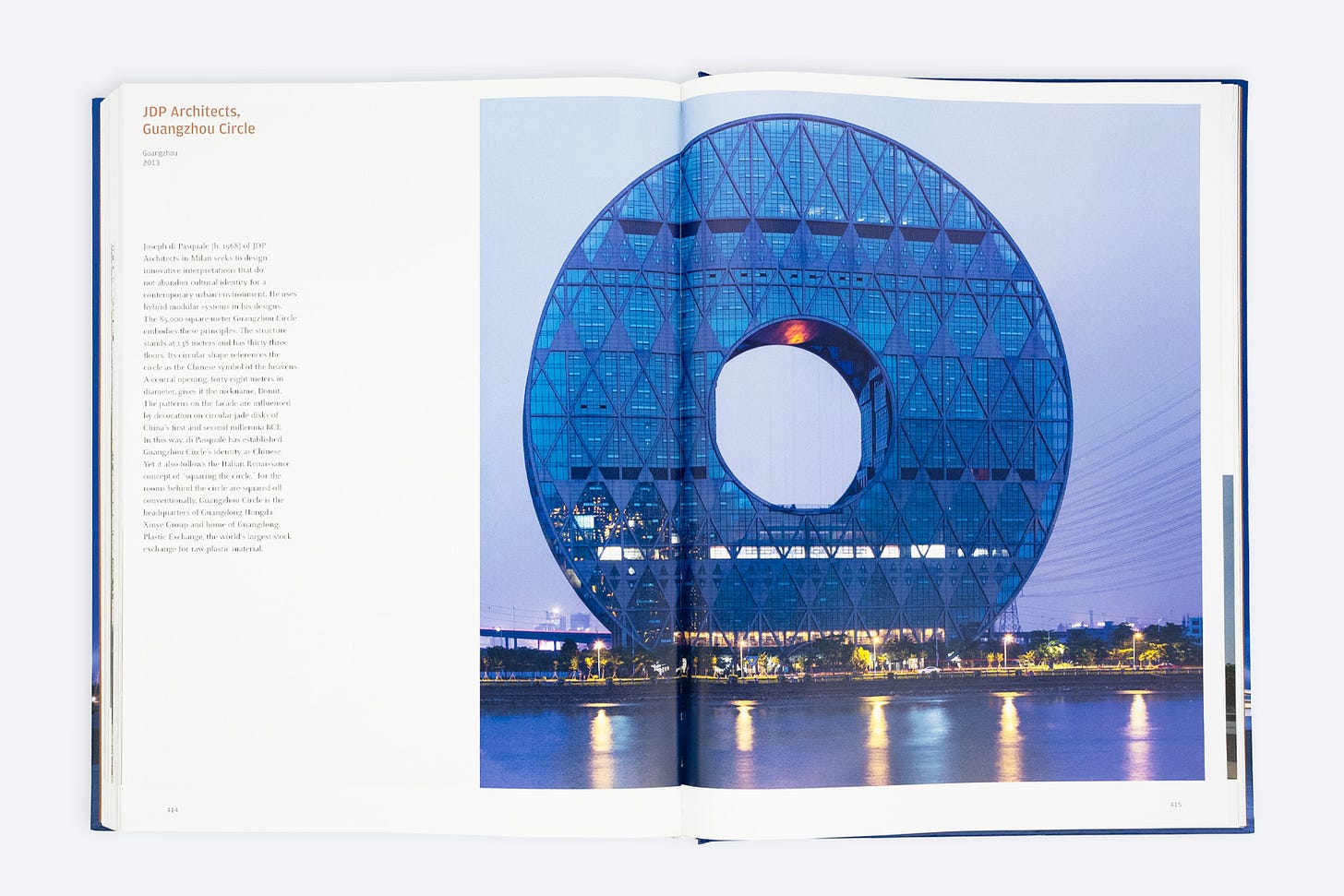

Although I’m disappointed by the lack of index, the dearth of information on many of the projects, and the rarity of interior compared to exterior photos, Steinhardt and company should be commended for the selection they pared down from the 500 contenders. I can’t think of another book on modern Chinese architecture that includes so many wide-ranging buildings in one place. Traditional pagodas and temple structures are here, as are Beaux-Arts, Art Deco, and other Western styles that were blended with local features, not to mention the plurality and formalism of contemporary China. The book may span 180 years, but the bulk of the buildings are found in the two chapters covering the years 1842 to 1912 and 2000 to present. As such, the reader gains an understanding of, in the first chapter, traditional Chinese architecture and the infusion of Western styles, and, in the last chapter, the icons of 21st-century architecture that were created by home-grown architects and others, like Koolhaas, who have “Gone East.”

Books Released This Week:

(In the United States, a curated list)

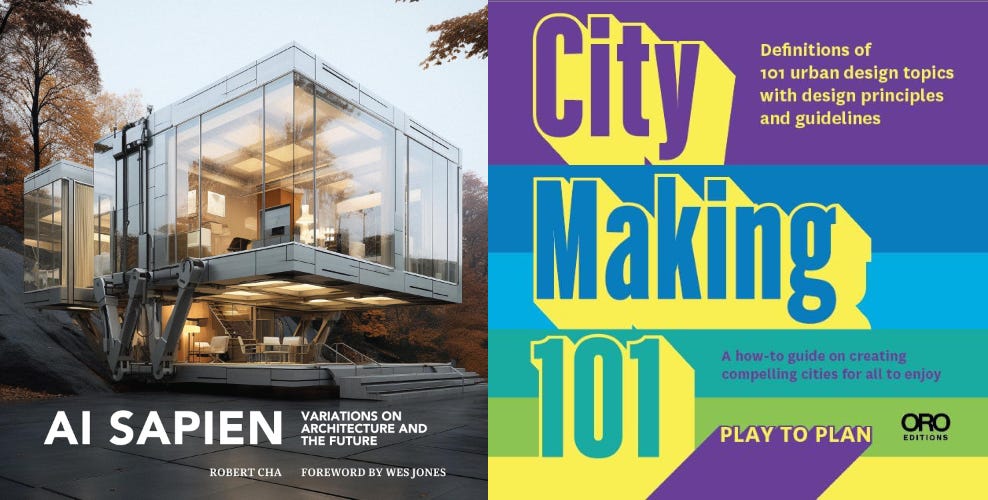

AI Sapien: Variations on Architecture and the Future by Robert Cha (Buy from ORO Editions / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — The hype over AI-generated architectural imagery has tapered off recently, but publishing is slow compared to digital platforms, so we should see more books like this “paradigm-shifting vision of the future where artificial intelligence (AI) transforms architecture into thinking machines” in the coming months and years.

City Making 101: Card Topics with Urban Design Guidelines by Alexis Sanal (Buy from ORO Editions / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — Not a book, City Making 101 is “a card game and reference resource for designers and ‘citizen designers’ to imagine, discuss and share ways to realize livable, lovable and walkable cities.” Too bad this book wasn’t released last week — it would have fit into that newsletter perfectly!

Here are a couple titles that were announced in this newsletter earlier this summer but are just now being released:

Into the Quiet and the Light: Water, Life, and Land Loss in South Louisiana by Virginia Hanusik (Buy from Columbia University / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — Photographs by Virginia Hanusik of an area hit by the double whammy of climate change and the fallout of the fossil fuel industry are accompanied by texts by scholars, artists, activists, and practitioners working in the region.

Noguchi's Gardens: Landscape as Sculpture by Marc Treib (Buy from ORO Editions / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — Marc Treib, who has written a book about Isamu Noguchi before, delves deeply into the landscape designs of Noguchi, “from his early unrealized projects for playgrounds and monuments to a large park in Sapporo, Japan, whose construction was completed only posthumously.”

Full disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, AbeBooks Affiliate, and Bookshop.org Affiliate, I earn commissions from qualifying purchases made via any relevant links above and below.

Book News:

The CBC delves into its archive to present a nearly one-hour interview with Peter Eisenman from 2011 on the Writers and Company podcast. Listen at Apple Podcasts.

Wallpaper* tours Karl Lagerfeld’s “extraordinary Paris library and bookshop, a haven for the bibliophile” that now hosts “a scintillating program of cultural events.”

Issues of Dimensions (University of Michigan Taubman College), Paprika! (Yale), and Thresholds (MIT) are recipients of the 2024 Douglas Haskell Award for Student Journals from the Center for Architecture/AIANY.

Architect's Newspaper editor Jack Murphy speaks with Jeanne Gang about The Art of Architectural Grafting, the monograph/manifesto published by Park Books earlier this year.

From the Archives:

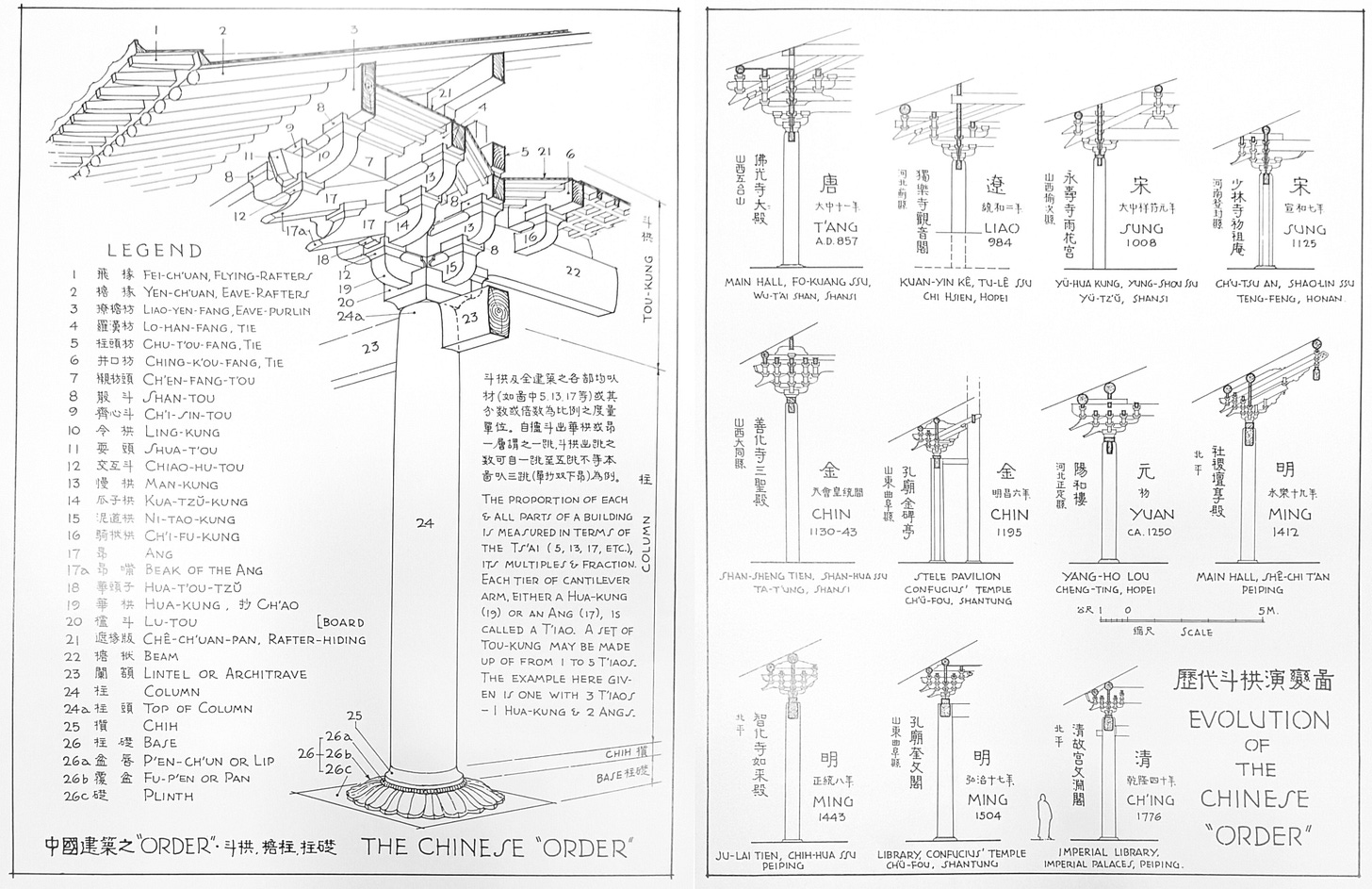

On a recent trip to Zurich for meetings with my colleagues at World-Architects, I asked Eduard Kögel, historian and curator of the Chinese-Architects platform, to recommend a book in English on architectural history in China. Without pause he mentioned architect Liang Sicheng (sometimes written as Ssu-chʻeng) and his A Pictorial History of Chinese Architecture: A Study of the Development of its Structural System and the Evolution of its Types, which was published by MIT Press in 1984, twelve years after he died at the age of 70. Liang wrote the book during World War II, after carrying out extensive field investigations in North China and the interior, but for various reasons (including the death of his wife in 1955) its publication was delayed so many years he would not see its completion.

Wilma Fairbank, who edited the English translation, describes the book in the front matter as “a brief survey of the great treasury of ancient Chinese architecture,” with a focus on its structural system, as the subtitle indicates. Across five chapters, Liang traces the orders of Chinese structural systems by looking at timber-frame buildings, Buddhist pagodas, and masonry structures. Liang actually intended for the book to be primarily visual, with “photographs and drawings of many typical specimens,” but “after the completion of the drawings, it seemed that a few words of explanation might be necessary.” As such, the text is relatively short for such a thorough history. But it’s the drawings by Liang and Mo Tsung-Chiang that make the book stand out:

A Pictorial History of Chinese Architecture is a rare and expensive book, so I opted to briefly look at the book at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Thomas J. Watson Library before deciding to invest in a copy or not. Two things stood out to me, both particularly interesting in the context of this week’s Book of the Week. First is the Penn connection: In the 1920s, sixty years before Nancy S. Steinhardt, in 1982, joined the University of Pennsylvania faculty, Liang and his future wife, architect Lin Huiyin, studied there under Paul Cret. Technically, Lin was not allowed to receive an architecture degree (she enrolled in the School of Fine Arts because the School of Architecture did not allow women), even though she took architecture classes — enough of them to earn a degree. Earlier this year, nearly 70 years after her death, she was given a posthumous Bachelor or Architecture, this per a story that happens to discuss the long Penn-China connections in architecture.

Second are Liang’s thoughts on modern architecture in China: “Can the traditional Chinese structural system find new expression in these new materials [concrete and steel]? Possibly. But it must not be the blind imitation of ‘periods.’ Something new must come out of it, or Chinese architecture will become extinct.” One of the buildings Liang designed, the National Central Museum (now Nanjing Museum) in Nanjing, which would have been under construction while he was writing the book (it was completed in 1948), is included in Steinhardt’s Modern Chinese Architecture.

Although traditional in appearance and seeming to belie Liang’s statement, the steel-framed and reinforced-concrete building is described by Steinhardt as “the convergence of traditional Chinese and modern architecture.” Today, more than 75 years after the museum’s completion, it can be seen as a hinge between imitation and innovation, between old orders built in new materials and much later new buildings, such as Amateur Architecture Studio’s Ningbo History Museum, literally made with old materials. While dramatically different in appearance, these two museums built sixty years apart are prized as honest expressions of Chinese culture.

Thank you for subscribing to A Weekly Dose of Architecture Books. If you have any comments or questions, or if you have your own book that you want to see in this newsletter, please respond to this email, or comment below if you’re reading this online. All content is freely available, but paid subscriptions that enable this newsletter to continue are welcome — thank you!

— John Hill