This newsletter for the week of August 26 heads to Indiana, specifically Columbus, the mecca of modern architecture that is the subject of a beautifully produced new book. Accordingly, I pulled a couple of books on Columbus off the shelf, and I present the usual new releases and book news. Next Monday is Labor Day, so I'm taking the week off and will resume the newsletter on Week 37, the week of September 9. Happy reading!

Book of the Week:

American Modern: Architecture; Community; Columbus, Indiana by Matt Shaw, photographs by Iwan Baan (Buy from Phaidon/Monacelli Press / from Amazon / from Bookshop)

Although an unlikely prospect, if I ever write a novel it will be about an architect who, as an expectant father, uses his talent and hubris to design and build all of the buildings his future child will use before reaching adulthood. Not liking what he sees around him, he designs new buildings in new ways for his new child. These buildings obviously include the child’s nursery and the family’s home, but also the day care, schools, playgrounds, and other spaces of education and play that the child will encounter throughout childhood and adolescence. Such a level of paternal control would result in some unforeseen, negative consequences, turning his utopian intentions into its near opposite — a bit like J. G. Ballard’s High-Rise, but without the cannibalism. While this hypothetical novel would surely comment on the egotistical nature of architects, especially the mythical solo genius in modern architecture, it would also have something to say about the role of society — of people outside of the family — in shaping an individual. While the architect-father means well in using architecture to help foster a positive upbringing for his child, his ignorance of the people who interact with his son/daughter inside and outside of his creations makes the ambitious “project” incomplete, flawed, and eventually disastrous.

I’m bringing up my far-from-fleshed-out idea for a novel in the context of American Modern, a book about modern architecture in a small Indiana city, because, if there were a scenario in which designing buildings in new ways — the buildings where people live, learn, work, play, and pray — came closer to a utopia than a dystopia, the best example would be Columbus. Like other architects, I’ve long known about Columbus, the town south of Indianapolis known as “Athens of the Prairie,” a “Modernist Mecca,” and other apt labels because of its many modern buildings designed by famous architects, much of it due to the patronage of J. Irwin Miller and the Cummins Corporation. But what made it click that such buildings as the First Christian Church by Eliel Saarinen, the Miller House and Garden by Eero Saarinen, and The Republic by Myron Goldsmith were more than just notable individual works of architecture (and National Landmarks, to boot) was this quote found on page 92 in Matt Shaw’s deeply researched history of Columbus:

Every one of us lives and moves all his life within the limitations, sight, and influence of architecture — at home, at school, at church, at work. The influence of architecture with which we are surrounded in our youth affects our lives, our standards, our tastes when we are grown, just as the influences of the parents and teachers with which we are surrounded in our youth affects us as adults.

American architecture has never had more creative, imaginative practitioners than it has had today. Each of the best of today’s architects can contribute something of lasting value to Columbus.

These words were part of a letter that Irwin wrote to Columbus school board president W. L. Wiseman in 1957, more than twenty years after Eliel Saarinen was commissioned to design First Christian Church, considered the first Modernist church in the United States and the beginning of Columbus’s embrace of modern architecture. Although written in the context of public schools, this quote, found in the book’s second chapter, “Total Community Project,” succinctly describes the values of the whole Columbus architectural project, which extended to churches, parks, offices, industrial buildings, shopping centers, community spaces, even golf courses. By the time readers encounter this quote, even those without any previous knowledge of Columbus should be starting to understand how the town ticks; how business and industry, with Miller and Cummins leading, were not solely interested in profit, but also in forming a strong Midwestern community and using architecture to assist it. Much of it makes sense from a business standpoint: How can you attract workers to the middle of Indiana if the schools are outdated, there is insufficient housing, and the things to do after work and on the weekends are lacking? For Miller and Cummins, that meant paying the architects’ fees via the Cummins Engine Foundation Architecture Program on projects, regardless of the client, as long as the selected architect was on CEF’s shortlist. As such, buildings designed by the Saarinens, Harry Weese, Gunnar Birkerts, I. M. Pei, Kevin Roche, and others are found all around town — an anomaly even compared to considerably larger American cities.

Numerous books have been written about the modern architecture of Columbus, Indiana, including an official Visitors Center guidebook and a photo book by photographer Balthazar Korab that are at the bottom of this newsletter; also notable for its focus on the patronage of Miller and Cummins is Nancy Kriplen's J. Irwin Miller:The Shaping of An American Town, published by Indiana University Press in 2019. But a more overarching history of the Columbus architectural project was lacking until the release of American Modern last month. Published by Monacelli with the involvement of the Landmark Columbus Foundation, the book is enriched by words and images that alternately provide insider and outsider viewpoints. Shaw is a writer who grew up in Columbus and Iwan Baan, whose full-bleed photos cover as many pages as Shaw’s text, hails from the Netherlands. Shaw worked on the book for years, but his background means he was figuratively working on it his whole life. Baan took thousands of his distinctive documentary-style photographs over the course of four trips to Columbus in 2021 and 2022, capturing the beauty of the buildings and landscapes but also how people use them. (The timing means that many of the photos inside buildings, especially schools, feature people wearing masks to stop the spread of Covid-19, putting an inadvertent visual timestamp on the book’s documentation of the town’s notable buildings.)

As early as the introduction, Shaw situates the modern architecture of Columbus within wider mid-20th-century goals for society, both in the town and in the federal government. The latter is spelled out in terms of John F. Kennedy’s New Frontier and Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society, which was a vision for American as “a place where the meaning of man’s life matches the marvels of man’s labor.” The seven chapters that follow provide a chronological yet thematic narrative of Columbus in the last half of the 20th century, highlighting “major projects” with Baan’s photos but also discussing other relevant works of architecture (both in and beyond Columbus) and situating the architecture within the town’s overarching progressive social history. So, we read descriptions of the various progressive schools, housing, and other projects while also learning about, for example, the Cummins Black Banking Project, which attempted to “finance Black homeowners and fight redlining.” In other words, progressive architecture and progressive social reforms went hand in hand.

The relevance of Columbus’s 20th-century architectural/social project today, when social justice and other issues are steering architectural culture more strongly than form, tectonics, and the like, is obvious. Columbus can serve as an example of how clients, architects, and users can work together to advance their varied interests — making a profit, designing something beautiful and useful, living enjoyably — while ultimately creating something that is larger than the sum of its parts. How that example works in the place itself, in Columbus, is also another way the book is timely; the town has to be constantly evolving, not resting on its unique history. Programs like the biennial Exhibit Columbus, billed as “an exploration of community, architecture, art, and design that activates the modern legacy of Columbus, Indiana,” are part of that evolution. American Modern, in a way, does its part: telling a fuller story of the town beyond its buildings and its main patron, Miller, and providing fodder for considering the town’s future in the 21st century.

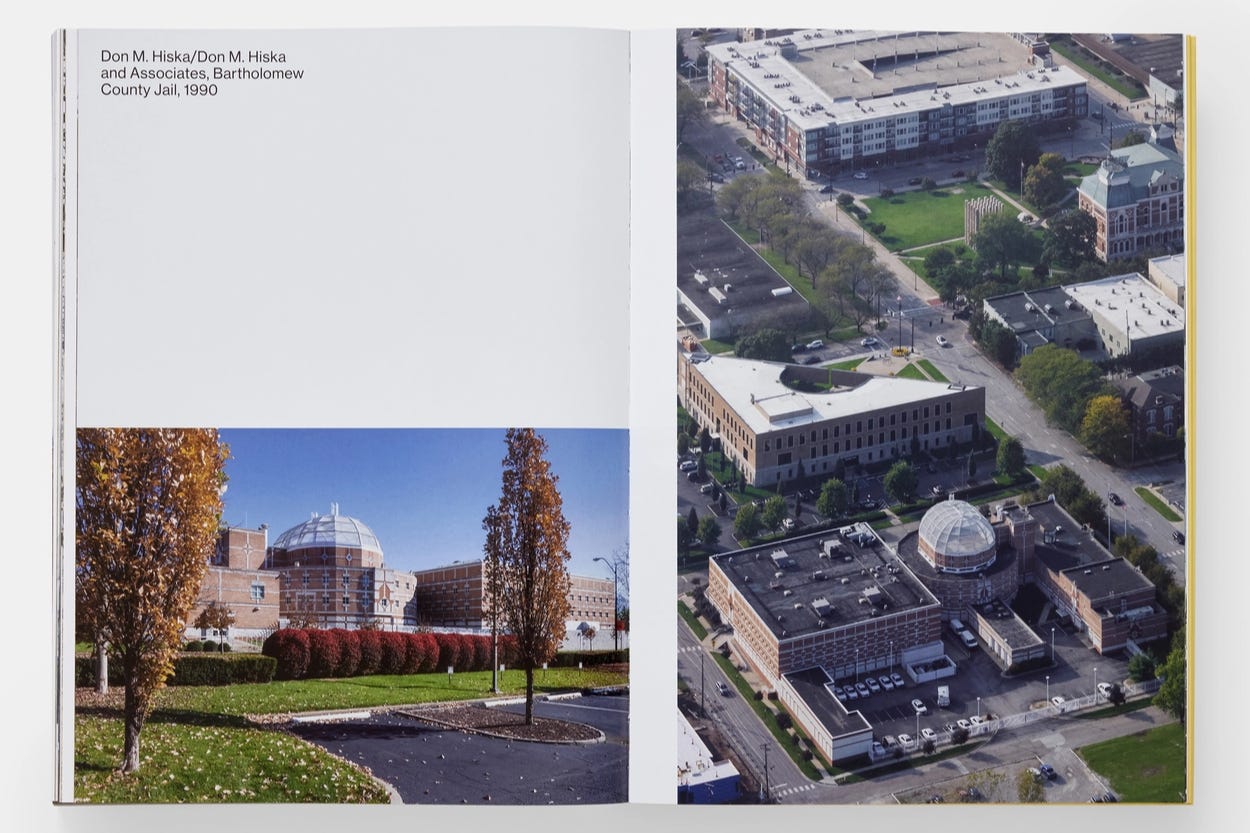

American Modern is an excellent book, due in large part to the contributions of Shaw and Baan but also, it should be mentioned, to the graphic design of Alex Lin. The reams of information and imagery is structured in a way that amplifies the text and photographs and makes the book easy to navigate; to wit, the “major projects” are underlined in the text, presented as thumbnails at the bottom of the same page, and keyed to the full-bleed glossy spreads at the end each chapter. The folded poster cover, with archival images on yellow paper, is a nice touch that is reiterated with the yellow pages at the start of each chapter and in the appendix, where an illustrated chronological list of projects and an extensive bibliography are found. (The only user-friendly feature not included, frustratingly, is an index.) Put another way, the important role of design in Columbus’s 20th-century realization extends to the design of the book, an integral aspect of the book’s presentation of the town’s history.

Books Released This Week:

(In the United States, a curated list)

Toward Re-Entanglement: A Charter for the City and the Earth by Philipp Misselwitz and Alan Organschi, edited by Bauhaus Earth (Buy from JOVIS / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — Bauhaus Earth convened an international team of scientists, architects, spatial planners, and policymakers to author a manifesto focused on redesigning the entire life cycle of the urban realm to positively address environmental and social crises.

Building Institution: The Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies, New York 1967-1985 by Kim Förster (Buy from Transcript Publishing / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — Fourteen years after Suzanne Frank self-published an “insider’s” account of the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies, Kim Förster turns his PhD from ETH Zurich on the IAUS into a book, which is available as a hardcover and as an open-access PDF.

The People’s Architect: Carol Ross Barney edited by Oscar Riera Ojeda (Buy from Oscar Riera Ojeca Publishers / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — This monograph celebrates Carol Ross Barney receiving the 2023 American Institute of Architects Gold Medal through a presentation of numerous public projects designed by her Chicago firm, Ross Barney Architects, including the Chicago Riverwalk, pictured on the cover.

Selected Works of Landscape Architect John L. Wong: From Private To Public Ground From Small To Tall by John L. Wong (Buy from Oscar Riera Ojeca Publishers / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — This monograph presents a comprehensive overview of the five-decade career of John L. Wong, the principal at SWA Group who has crafted landscapes for a dozen of the hundred tallest buildings in the world, including Burj Khalifa, pictured on the cover.

Full disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, AbeBooks Affiliate, and Bookshop.org Affiliate, I earn commissions from qualifying purchases made via any relevant links above and below.

Book News:

In “What Does Your Home Say About You?” at Untapped Journal, Shane Reiner-Roth revisits Norma Skurka’s 1972 book Underground Interiors, applying its countercultural lessons to the "thirtysomethings of today."

Drawing Matter excerpts architect Anna Kostreva's Seeing Fire | Seeing Meadows, which Holger Kleine describes as a “sophisticated” book that sits in its own genre, “which one might call ‘archifiction.’”

If you like drooling over photographs of libraries in shelter mags, this is for you: “Top Shelf: Four drool-worthy home libraries” at Toronto Life.

From the Archives:

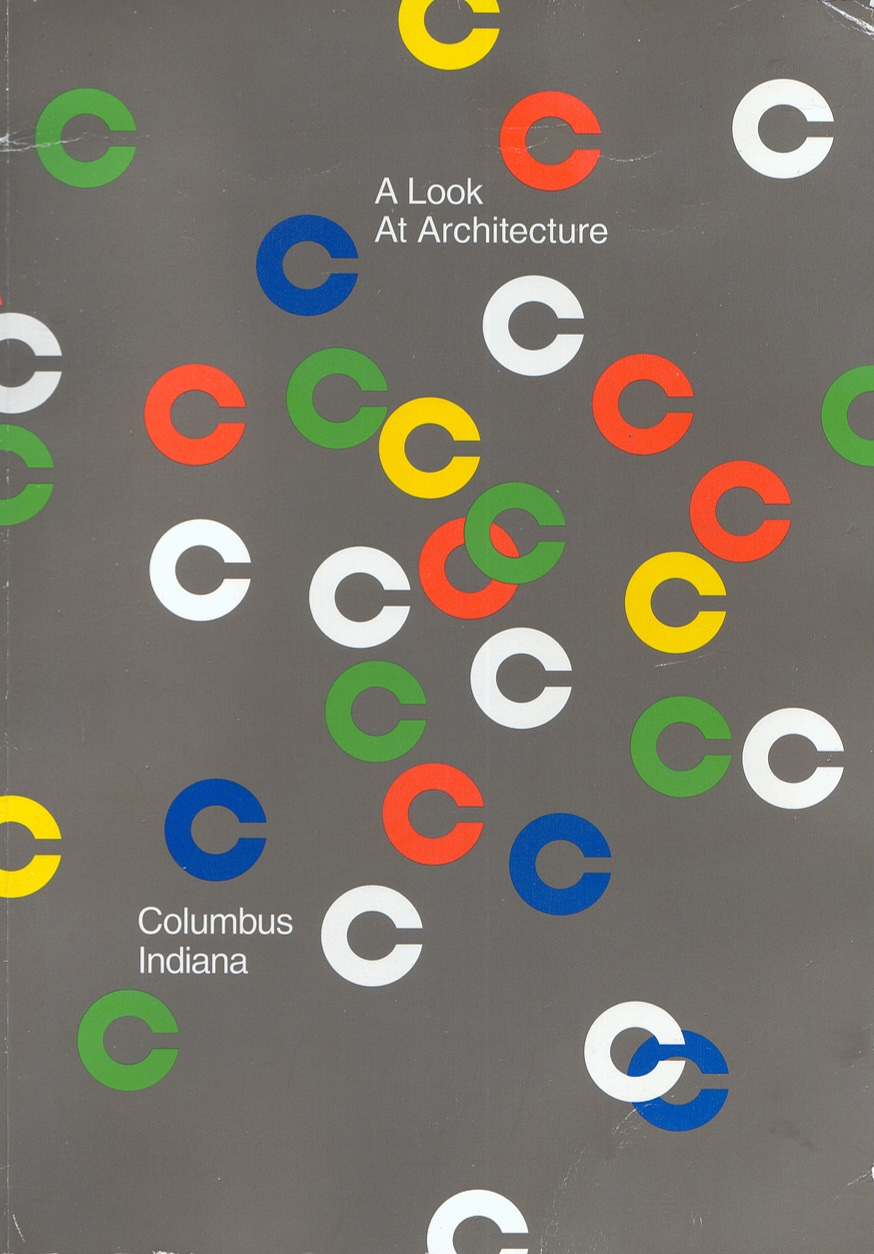

A full fifty years before the release of American Modern, this week’s Book of the Week, the Columbus Area Chamber of Commerce published A Look at Architecture: Columbus, Indiana. The book was designed by Paul Rand and has been updated roughly every five years since the first edition in 1974. The seventh edition that I have was published in 1998, two years after Rand’s death, and as such it “return[ed] to his original 1974 design for the cover.” The design is one of the most appealing aspects of the book, from its recognizable cover to the gray linen card stock used for the leaves at the front and back of the book, and the simple spreads presenting the modern architecture built in Columbus after 1941, most of it documented with photographs by Balthazar Korab (1926–2013). Given that new copies of the book could only be purchased at the Visitors Center Gift Shop, the book is a helpful guide for archi-tourists but also acts as a souvenir for them. People who make the trip now will encounter the ninth edition, published in 2019 in what appears to be a wider paper size and featuring additional color photography (plus Korab’s historical photos), a revised text that is longer than the seventh edition, and a new page layout befitting the larger pages. Although it’s been five years since that update, the release of American Modern makes the publication of a tenth edition much less urgent.

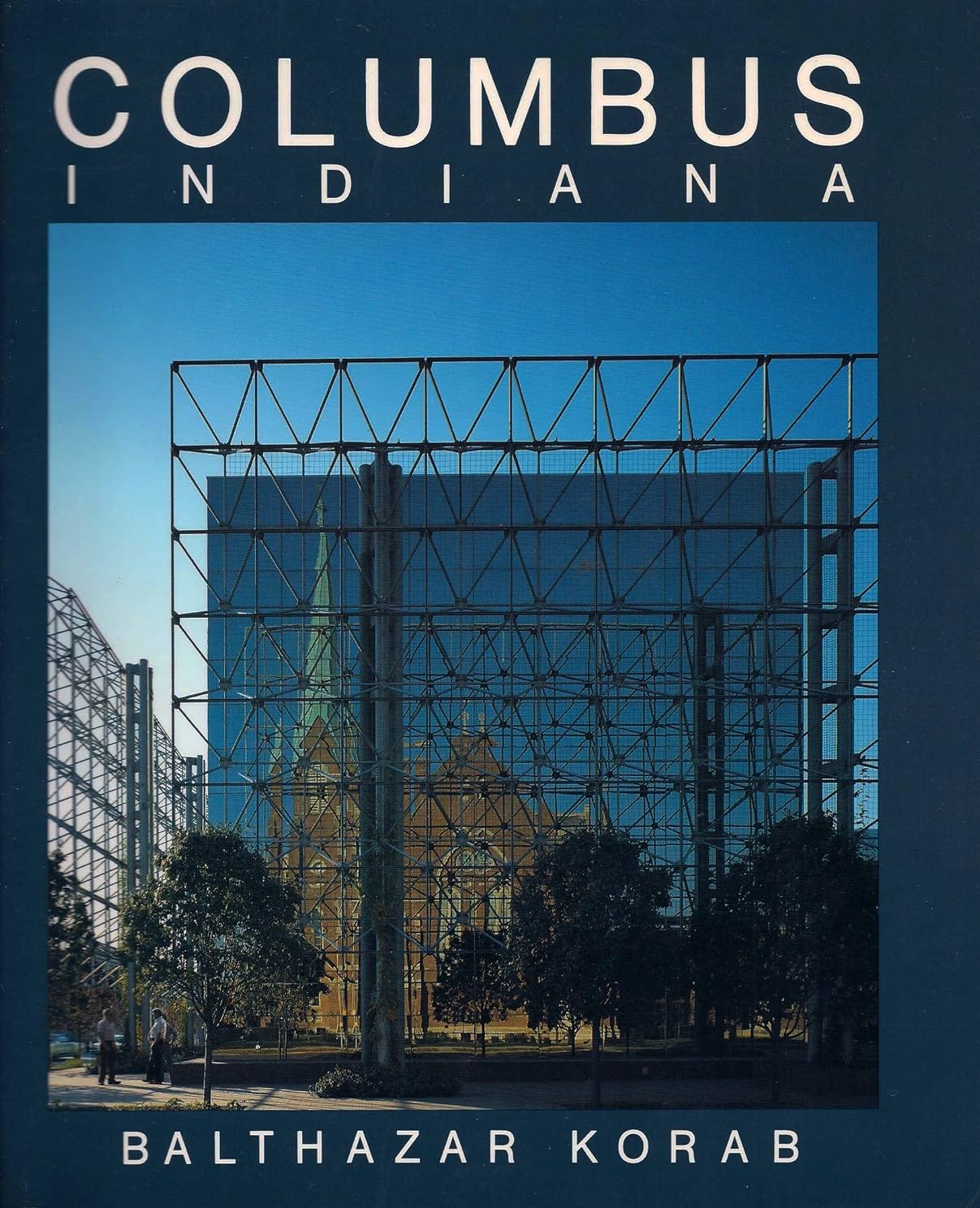

If you thought A Look at Architecture contained all of photographer Balthazar Korab’s output on Columbus, then you’ll be pleasantly surprised by Columbus Indiana: An American Landmark. Published by Documan Press in 1989, the book not only goes beyond the photographic documentation of the Chamber of Commerce publication, offering additional photographs of the town’s famed modern buildings as well as some beautiful shots of the Midwestern landscapes around the town, it also includes some reminiscences and other words from Korab. Accordingly, An American Landmark is part photo book, part memoir, and part first-person, behind-the-scenes history of the place. Of greater relevance here, in a newsletter topped by a book featuring Iwan Baan’s photos of Columbus, are the occasional photos, especially in the final, “sense of place” chapter, in which Korab captures architecture as a backdrop to life in the town: children playing, church congregations, and a parade, among others. Though 35 years out of date, An American Landmark is valuable as a beautiful and honest portrait in images and words of the Midwestern mecca for modern architecture.

Thank you for subscribing to A Weekly Dose of Architecture Books. If you have any comments or questions, or if you have your own book that you want to see in this newsletter, please respond to this email, or comment below if you’re reading this online. All content is freely available, but paid subscriptions that enable this newsletter to continue are welcome — thank you!

— John Hill

Thank you, Mr. Hill.

I first learned about Columbus' architectural heritage through Kogonada's Columbus (2017) with John Cho and Haley Lu Richardson. The movie relies heavily on the city's architectural marvels to provide support for its amazing screenplay (where the son of an architecture scholar befriends an architecture enthusiast) and I just couldn't stop pausing the movie every five minutes or so to stare at the amazing frames with the unbelievable architecture as the centerpiece.

What makes everything more interesting here is that I work in the architecture, engineering, and construction (AEC) industry as a project manager and I've been working with Cummins generators for pretty much my entire professional career (almost 10 years working now) and I didn't know about this very important aspect of Cummins' history particularly given my enthusiasm for architecture, particularly modern and brutalist architecture (Paul Rudolph is my favorite architect), so thank you so much for sharing all of this. I'll definitely try to visit Columbus one day and, of course, I'll try to get my own copy of American Modern.