This newsletter for the week of September 9 heads to Australia — well, virtually, at least — to look at a book of unbuilt projects designed by Glenn Murcutt. That “Book of the Week” is accompanied by two other Murcutt monographs “From the Archive.” In between are the usual headlines and, to catch up after our week off last week, an extra-long list of new books. Happy reading!

Book of the Week:

Glenn Murcutt: Unbuilt Works by Nick Sissons (Buy from Thames & Hudson / from Amazon / from Bookshop)

One would think that the fame and renown of architect Glenn Murcutt, the only Australian architect to have so far won the Pritzker Architecture Prize, would lead to a slew of books about him. That is not the case. Most famous and lasting is Leaves of Iron by Philip Drew, first released in 1985 and discussed at the bottom of this newsletter. But since Murcutt’s Pritzker in 2002, I count fewer than ten books devoted to his buildings, most of them over a decade old. Two of them happened to follow soon after the Pritzker: Haig Beck and Jackie Cooper’s A Singular Architectural Practice, also discussed in the “From the Archives” section at the bottom of this newsletter, and Glenn Murcutt: Buildings and Projects 1962-2003, a career-spanning monograph written by Francoise Fromonot. The latter was published in 2003 by Thames & Hudson, who is also this week releasing the latest book on Murcutt, a monograph presenting ten of his unbuilt works.

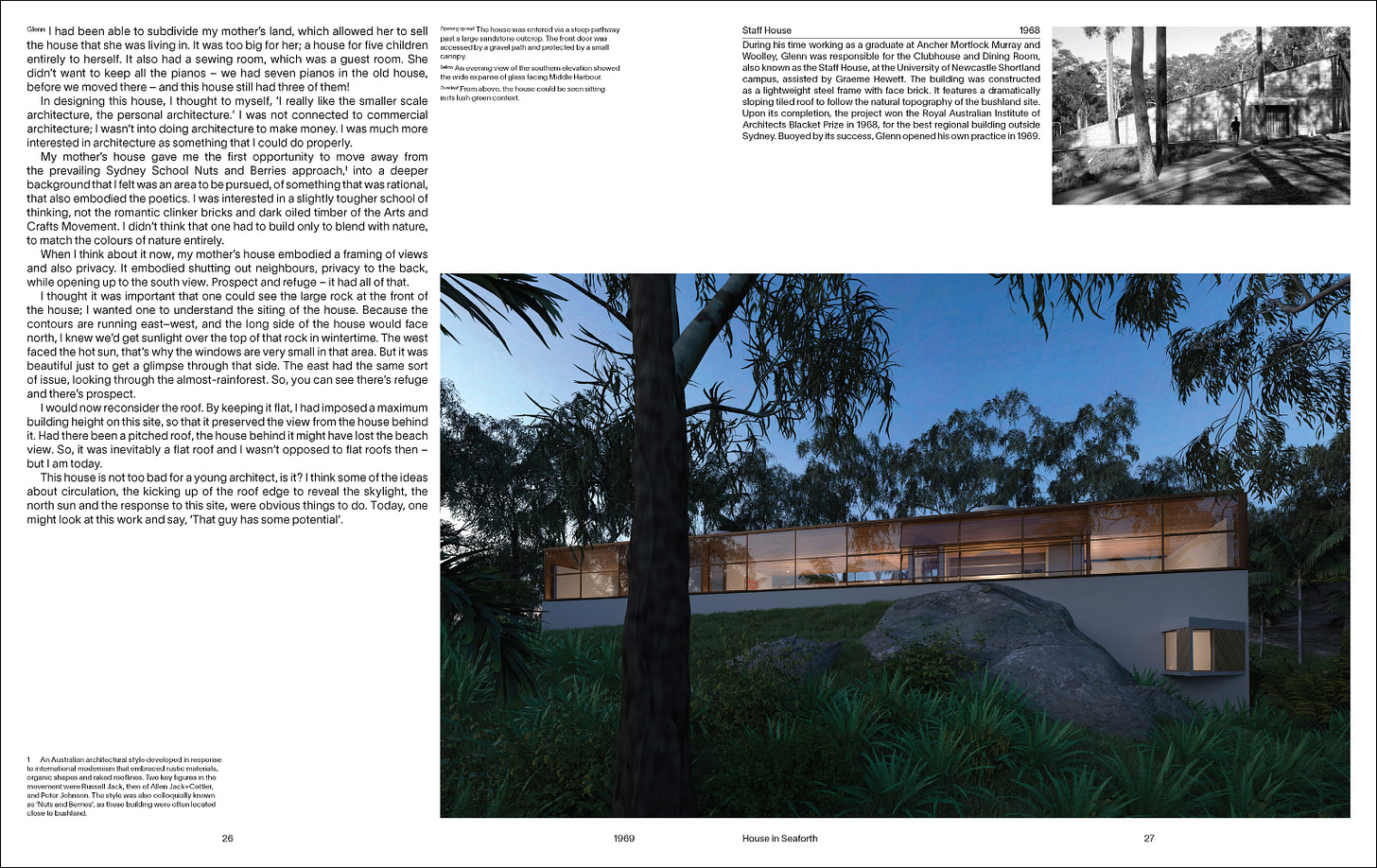

The popularity of coffee table books devoted to unbuilt architecture is a good sign that both architects and non-architects like to imagine what could have been, especially when unbuilt designs are expressed through colorful renderings. Murcutt is an architect known for his solo practice, hand drawings, and focusing on tectonics and how buildings relate to the landscape — things that are never explained via renderings. I’ve seen plenty of sketches and construction drawings from his hand, but never a rendering. Accordingly, Murcutt seems like one of the last architects to be given a book of unbuilt works through the Kahn treatment — that is, having his unbuilt projects digitized and presented as computer renderings. Murcutt’s buildings — houses in the landscape, mainly, but also suburban houses and occasional cultural buildings — exude quiet and find appreciation in their details. These are qualities, I think, that are difficult to capture in renderings.

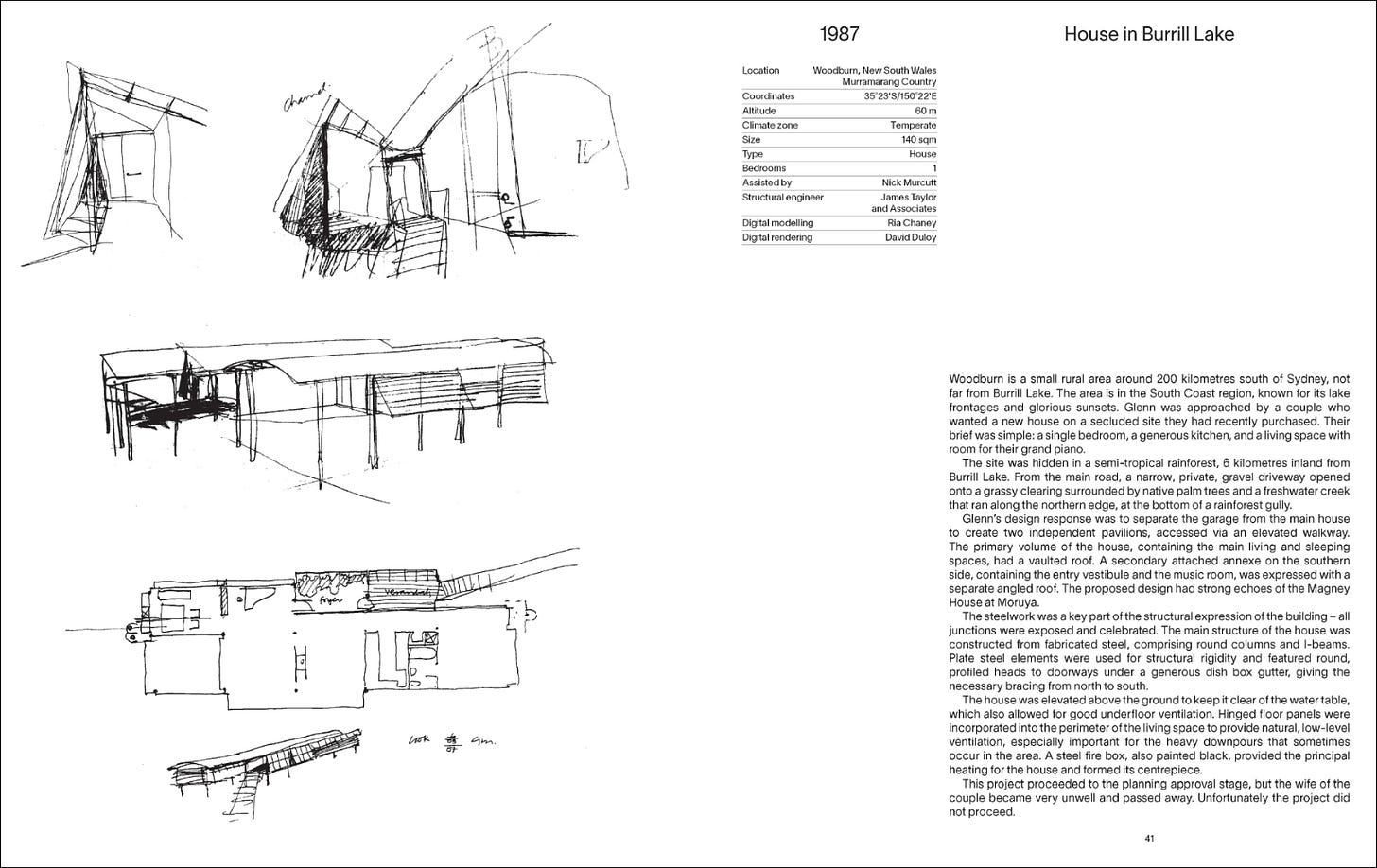

Perhaps because of my resistance to the idea, I was pleasantly surprised by the renderings accompanying the sketches and hand drawings, redrawn floor plans, and insightful descriptions (by both Nick Sissons, a former student and colleague of Murcutt’s, and Murcutt himself) of the ten unbuilt works — seven houses, a museum, a community center, and a hotel. The renderings don’t try be atmospheric or moody. The renderings are realistic, to be sure, but they are matter of fact, both in terms of the architecture and the landscapes the buildings would have sat within. Without the renderings, especially non-architects would have had a hard time grasping the qualities of the unbuilt works as potential buildings and understanding why these ten buildings, and not ten others, were selected. In service of the latter, each unbuilt work is accompanied by a brief “case study”: a built work by Murcutt that has formal and/or tectonic similarities with the unbuilt work. Those familiar with his buildings will no doubt see those precedents — via the butterfly roofs, curved sections, deep overhangs, etc. — in their minds before they see them on the page. Such is the unmistakable nature of Murcutt’s architecture.

Given how Murcutt’s buildings have clear signatures, the most rewarding unbuilt works are the ones that surprise, that depart from his distinctive formal and tectonic toolboxes. For me, these include the Silver City Mining Museum (1988), which has an oversized gabled roof truss lifted on slender columns high above rammed earth walls and a series of malqafs (wind scoops); the large House on the Central Coast (1997), which is split into two halves programmatically and linked by a covered patio; and the Hotel in Moonlight Head (2002, in collaboration with Wendy Lewin), a remote eco-hotel with projecting window boxes reminiscent of the Arthur and Yvonne Boyd Education Centre. These and the other projects met unfortunate ends for different reasons, all of them spelled out in the book’s pages. But with the realistic renderings, readers can imagine they exist — this is not much a stretch, really, given that many readers have as small a chance experiencing an actual Murcutt building as they do experiencing one of these unbuilt works.

Books Released This Week:

(In the United States, a curated list; this week’s list is longer than usual since it also features books from last week’s Labor Day holiday.)

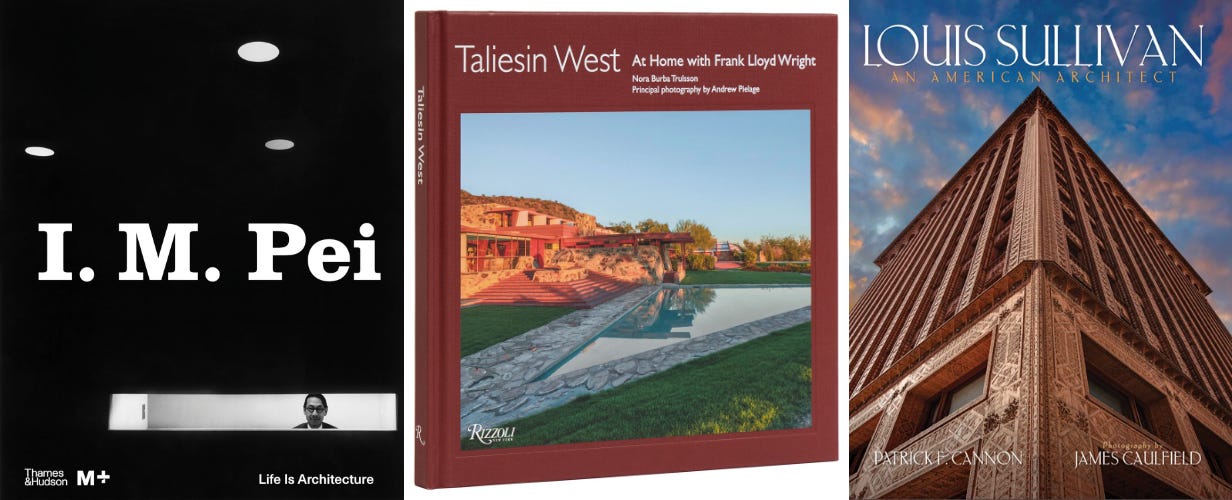

I. M. Pei: Life Is Architecture by Shirley Surya and Aric Chen (Buy from Thames & Hudson / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — This companion to the large-scale retrospective now at M+ in Hong Kong takes the same thematic view as the exhibition, with six chapters focusing on “Pei’s Cross-Cultural Foundations,” “Real Estate and Urban Redevelopment,” “Art and Civic Form,” “Power, Politics, and Patronage,” “Material and Structural Innovation,” and “Reinterpreting History through Design.”

Taliesin West: At Home with Frank Lloyd Wright by Nora Burba Trulsson, photography by Andrew Pielage (Buy from Rizzoli / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — Taliesin West, the desert compound outside Phoenix that Frank Lloyd Wright started building in 1937, is the subject of a new coffee table book that features archival images alongside new photography.

Louis Sullivan: An American Architect by Patrick F. Cannon, photography by James Caulfield (Buy from University of Minnesota Press [distributor for Glessner House] / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — Photographer Caulfield and writer Cannon have collaborated on books on Chicago and the architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright. Fittingly, their latest documents every extant structure designed by Louis Sullivan.

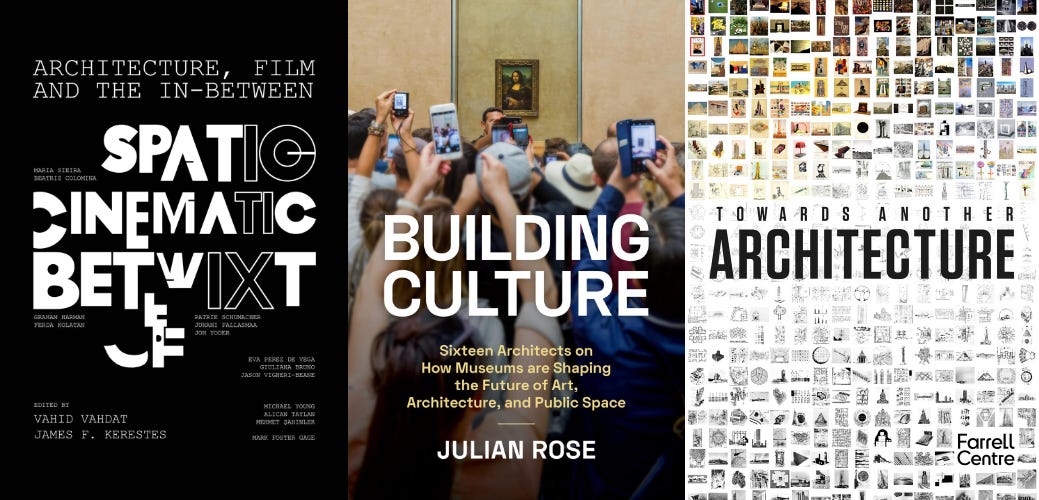

Architecture, Film, and the In-between: Spatio-Cinematic Betwixt edited by Vahid Vahdat and James F. Kerestes (Buy from Intellect Books / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — Architects, philosophers, and other thinkers — including Juhani Pallasmaa and Beatriz Colomina — explore the works of John Lautner, David Lynch, Christopher Nolan, Agnès Varda, Mies van der Rohe, and others with “diverse approaches to the liminal space between architecture and film.”

Building Culture: Sixteen Architects on How Museums Are Shaping the Future of Art, Architecture, and Public Space by Julian Rose (Buy from PA Press / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — Rose started interviewing architects who design museums while senior editor at Artforum from 2012 to 2018. This new book collects the project that he developed further in the subsequent years, featuring interviews with David Chipperfield, Elizabeth Diller, Steven Holl, Annabelle Selldorf, Peter Zumthor, and eleven others.

Towards Another Architecture: New Visions for the 21st Century by Owen Hopkins (Buy from Lund Humphries / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — Hopkins, previously senior curator at Sir John Soane's Museum and now director of the Farrell Centre, argues that, one hundred years after Le Corbusier’s Vers une architecture, the crisis-ridden world needs “an architecture that is not bound to a single vision or future, but is diverse, pluralist and sustains multiple conversations about the active role that architects might play in the world.”

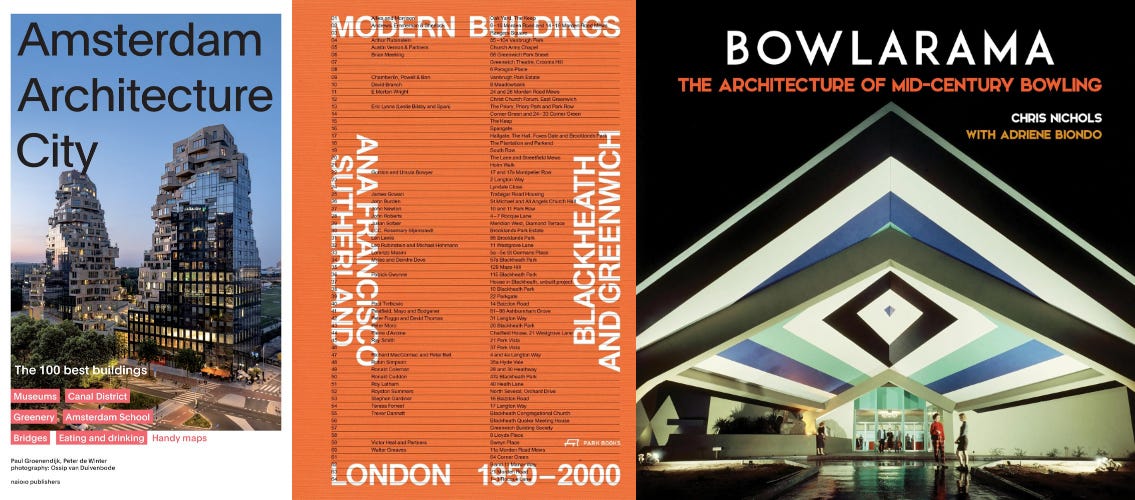

Amsterdam Architecture City: The 100 Best Buildings by Paul Groenendijk and Peter de Winter (Buy from nai010 publishers/DAP / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — Just like the title says, this guidebook presents “expert insights” on the hundred best buildings in Amsterdam, as well as tips on what to do around the city.

Modern Buildings in Blackheath and Greenwich: London 1950–2000 by Ana Francisco Sutherland (Buy from Park Books/University of Chicago Press / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — The author's extensive research on two districts in the southeast of London over the second half of the 20th century presents images, plans, and concise texts on 65 individual buildings and housing developments by 38 architects.

Bowlarama: The Architecture of Mid-Century Bowling by Chris Nichols with Adriene Biondo (Buy from Angel City Press / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — Vintage photographs, “exciting ephemera,” and detailed hand-drawn architectural renderings capture the mid-century obsession with bowling and the bowling alleys that sprang up to feed the craze.

The Complete Guide to Combat City by Julia Schulz-Dornburg (Buy from JOVIS / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — This unconventional guidebook presents 17 “simulated cities, exclusively developed by the military,” reconstructed from existing video footage, satellite images, military photographs, and army supplier’s catalogs.

The Green Dip: Covering the City with a Forest by The Why Factory (Buy from nai010 publishers/DAP / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — The latest book from The Why Factory (t?f), the research group at TU Delft headed by MVRDV’s Winy Maas, presents “a series of visualizations and data analyses of various ‘greened’ cities,” including Hong Kong, São Paulo, and Dubai.

Territorial Urbanism Now!: Call for a Social and Ecological Urban Planning and Design edited by Institut für Städtebau, et. al. (Buy from JOVIS / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — Just as architects are embracing maintenance and reuse of existing buildings over new construction as means of collectively tackling the challenges of climate change, this book asks, “What if urban planning and design were to prioritize rather than merely accommodate the unbuilt environment?”

Full disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, AbeBooks Affiliate, and Bookshop.org Affiliate, I earn commissions from qualifying purchases made via any relevant links above and below.

Book News:

The New York Times features the 74-sf — yes, 74 square feet! — Rotterdam apartment of architects Beatriz Ramo and Bernd Upmeyer, the latter of whom is editor of MONU, the magazine I featured on my blog numerous times.

Thirteen publications are among the 33 grants the Graham Foundation awarded to organizations last week, with highlights among them being Beyond Closure: Reimagining Possibilities for Chicago’s Closed Schools (Borderless Studio and MAS Context), Frederick Kiesler: Vision Machines (The Jewish Museum), and Ethical Narratives: Essays by Richard Ingersoll (1949–2021) (Syracuse University – School of Architecture).

The Architect's Newspaper reports on Axiomatic Editions, a new imprint from ORO Editions "that locates its interests at the intersection of art, architecture, and design" and has books by Toshio Nakamura (A+U), Kenneth Frampton, and four others lined up for 2025.

From the Archives:

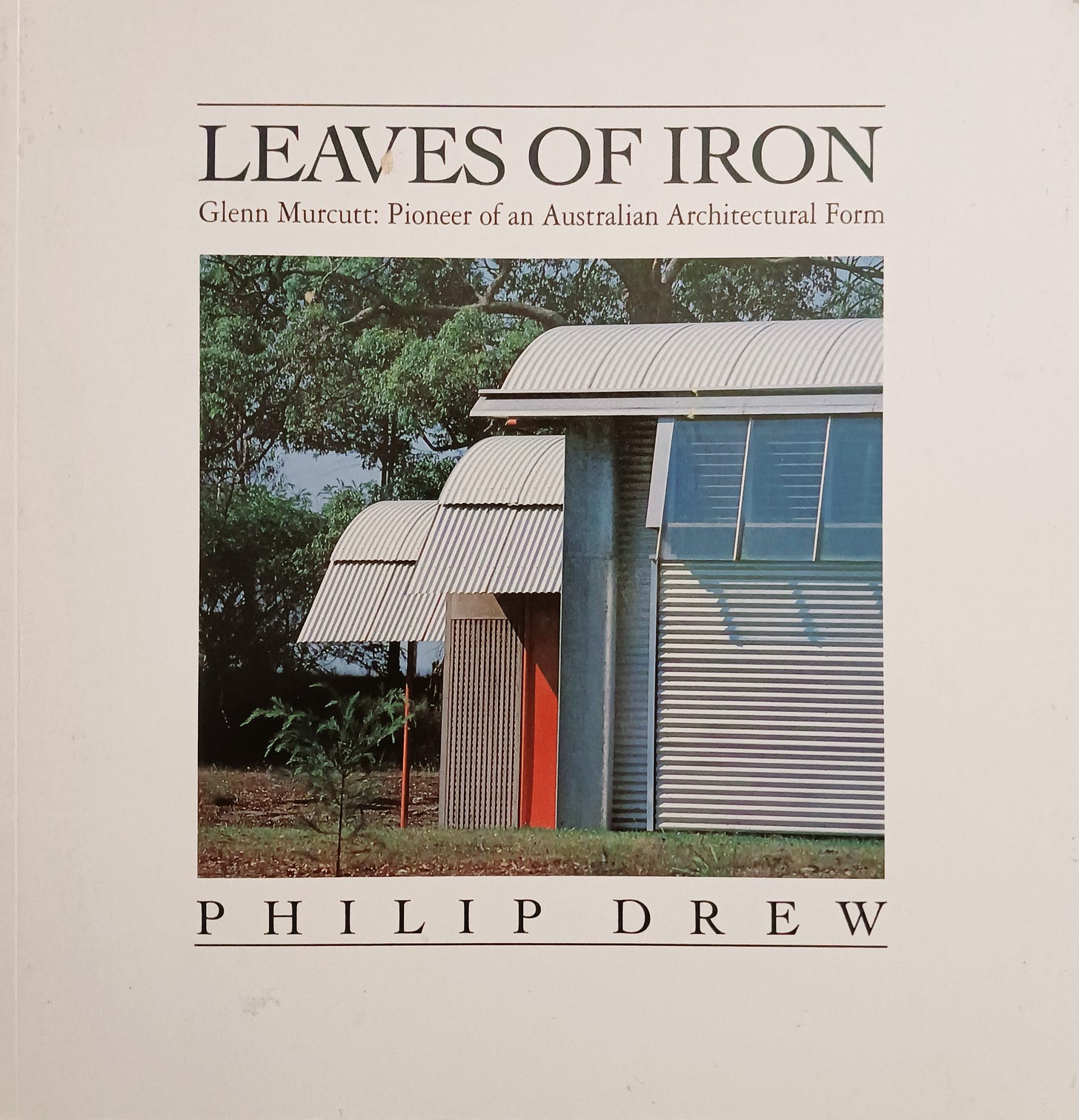

Back in September 2021, right after Glenn Murcutt was named the 2021 laureate of a Praemium Imperiale, I reviewed Philip Drew’s Leaves of Iron: Glenn Murcutt, Pioneer of an Australian Architectural Form on my blog. The famous book was first published by The Law Book Company Limited in 1985 and then reprinted by Angus&Robertson in 1991. It is the first comprehensive monograph on Murcutt and, with Drew’s many hours of interviews with the architect and the book’s lengthy word count, it is as much a biography and critical appraisal as a monograph. I wrote that the book “is considered a classic and arguably paved the way for an international appreciation of the architect that led to his Pritzker Prize win in 2002.” In hindsight (I bought the book around the time of my review, 30 years after its reprinting), the book was audacious and prescient: “The depth of Drew's writing on Murcutt's life and architecture is exceptional, particularly for an architect not yet fifty years old; the American equivalent would have been a biography on Frank Gehry in 1978, the year he completed his own house but decades before Bilbao and other notable buildings — and 37 years before Paul Goldberger's biography on him was actually published. Drew, in other words, had some foresight with the decision to write a voluminous book on a single architect, one that would frame Murcutt as an architect ‘pioneering’ a truly Australian architecture and define the way others viewed his architecture, including the Pritzker Prize jury.”

In my review of Drew’s book I also mentioned how “the monographic component of Leaves of Iron is not as thorough or beautiful as Haig Beck and Jackie Cooper's later Glenn Murcutt: A Singular Architectural Practice,” which I briefly reviewed on my blog in 2005, three years after it was published by Images. Beck and Cooper were founders and editors of UME, the exceptional large-format magazine that presented an abundance of working drawings on buildings both in Australia and beyond (to wit). Likewise, one of the three sections in their book on Murcutt is devoted to working drawings; the other two feature essays by the authors and the architect with detailed descriptions of Murcutt's design process, and a presentation of projects, primarily built houses. I wrote at the time: “Through the projects we see an evolution from Miesian, flat-roof designs executed when he started his practice in the late 1960s to his more popular angular and curved roof sections done in corrugated metal. Along the way we see how Murcutt's linear plan usually arrives after initial ideas (usually courtyard) don't work, and we see a number of suburban houses Murcutt has completed. The consistent qualities among all his buildings are their relationship to nature and culture, the way they are derived from natural elements, be they typical (heat/cold, wind, rain) or atypical (insects, wildfires, snakes), and the way the buildings respond to their context and the client's wishes. These responsibilities result in structures that not only tread lightly upon the land but also function in a way that — as Murcutt describes — ‘great poetic potential arises from the utilitarian.’”

Thank you for subscribing to A Weekly Dose of Architecture Books. If you have any comments or questions, or if you have your own book that you want to see in this newsletter, please respond to this email, or comment below if you’re reading this online. All content is freely available, but paid subscriptions that enable this newsletter to continue are welcome — thank you!

— John Hill