This newsletter for the week of October 14 features two Books of the Week. Both of them overlap with some personal history, so I’m using them as excuses to take trips down memory lane. The books From the Archive at the bottom of the newsletter echo the Books of the Week, while in between are the usual newly released books and architecture book headlines. Happy reading!

Books of the Week:

Broadly put, the two books featured here are histories of American architecture, both generously illustrated, but in their specifics there are widely divergent. One focuses on an architect who bridged the 19th and 20th centuries and designed buildings that were modern yet were inspired by nature and did not break sharply from the traditional architecture of its time. The other book documents a short-lived niche typology that has been overlooked in histories of architecture. Personally, both books resonate with me in terms of family history and personal experience. The first book is:

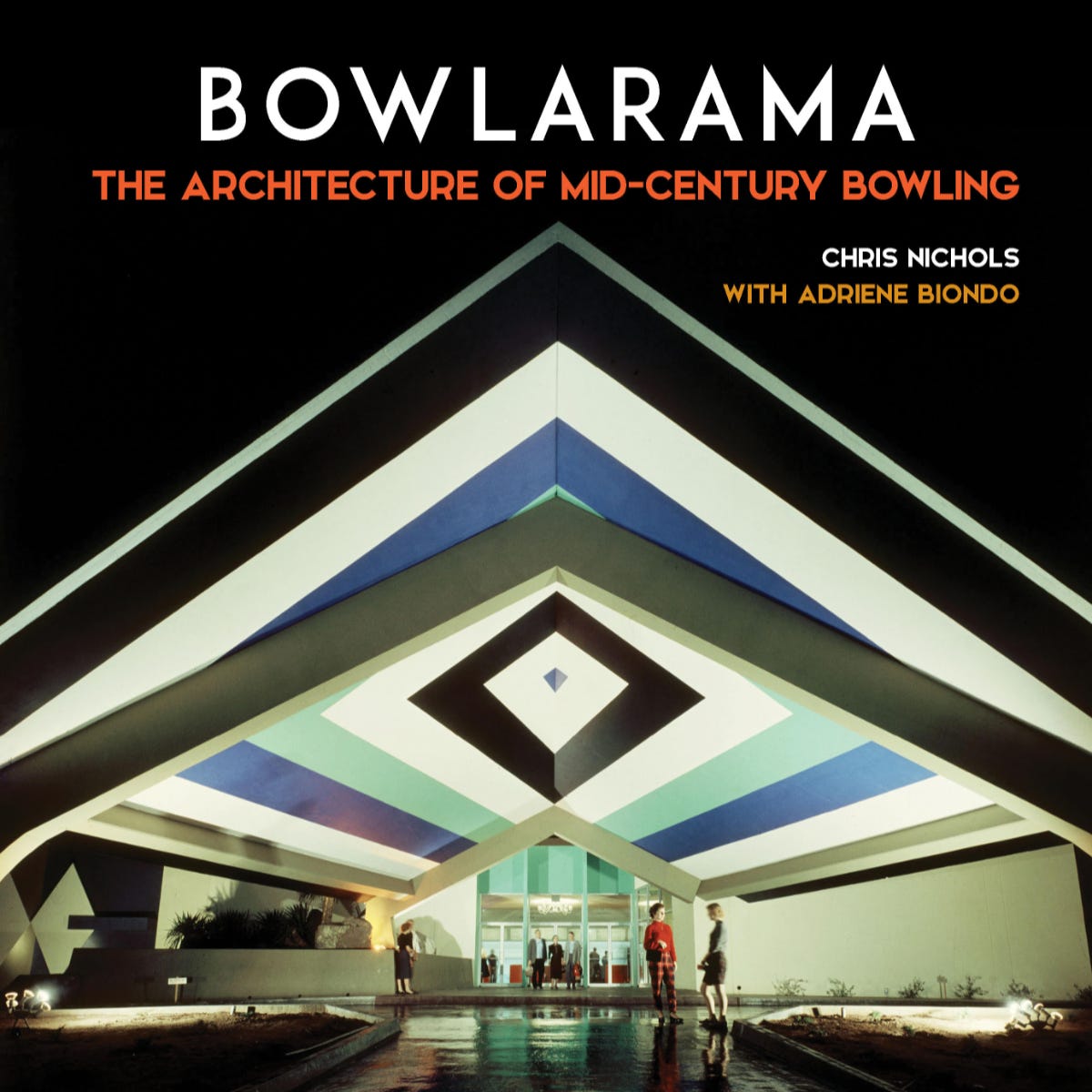

Bowlarama: The Architecture of Mid-Century Bowling by Chris Nichols with Adriene Biondo (Buy from Angel City Press / from Amazon / from Bookshop)

In the 1960s, both of my parents worked in the Chicago Loop office of Brunswick, the maker of bowling, billiards, and other leisure sports equipment. Instead of making their first acquaintance in the office, as one might expect, they met one evening after work, when groups of young Brunswick employees went to the bowling alley at Marina City, the Bertrand Goldberg-designed mixed-use complex just north of the Loop. The two corn-cob apartment towers opened in 1963 and the bowling alley, Spencer’s Marina City Bowl, opened in the second floor of the office slab in 1965, arguably the heyday of bowling in the United States. The alley closed thirty years later, in 1995, but then reopened in 2000, after the office floors were turned into a hotel. My parents would not have recognized the newly renovated alley, with its “Extreme Bowling” featuring loud music, black lights, and laser shows — an alley I happened to bowl at regularly as part of a league made up of various architecture offices.

Although Marina City Bowl originally had decor that echoed many of the roughly 12,000 alleys in the US in the 1960s, the facility was basically invisible from the outside, housed as it was in an office building. Not so the mid-century bowling alleys that populate Bowlarama: The Architecture of Mid-Century Bowling, a colorful book by Chris Nichols and Adriene Biondo that was published last month by Angel City Press, which is part of the Los Angeles City Library and “produces highly illustrated books about Los Angeles and Southern California, with particular emphasis on art, architecture, photography, design, and cultural history.” Nichols curated the 2014 exhibition Bowlarama: California Bowling Architecture 1954-1964 at the A+D Museum in Los Angeles and suitably the Bowlarama book predominantly features alleys in California, where standalone buildings for bowling made strong architectural statements at the time — inside and outside. Take the cover image, Bowlero San Diego (1957) by Paderewski, Mitchell and Dean, or Covina Bowl (1956) by Powers, Daly & DeRosa, which the authors describe as “gloriously googie.” The book ventures elsewhere, such as Orchard Twin Bowl (1959) by Richard Barancik in Skokie, a suburb of Chicago, but the book will appeal mostly to fans of mid-century modern architecture in Southern California.

Bowlarama celebrates the design of bowling alleys built in the 1950s and 60s through many archival photographs, renderings, and other images, but it also tells the history of bowling, looks at how technology changed the game, speaks about some of the architects who designed the lanes, and looks at how the sport rose and fell quite rapidly. Even though bowling remains an extremely popular sport in the US to this day, it grew so fast after the introduction of the automatic pinsetter in 1952 that, by 1962, there were too many alleys compared to demand and bowling “fell off a cliff,” in the authors’ words. As such, most of the bowling alleys presented in Bowlarama were built in the last 1950s and, unfortunately, many of them were bulldozed in the 1990s and 2000s, as the sad photos in the last chapter attest. Thankfully, Nichols and Biondo finish the book with “A Guide to the Remaining Mid-Century Bowling Centers” — a list with more extant lanes than you might expect.

On to my second trip down memory lane:

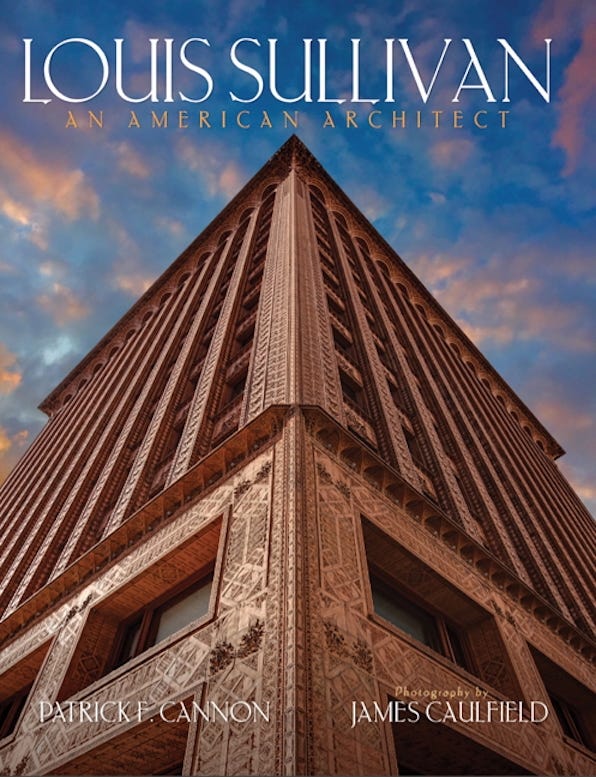

Louis Sullivan: An American Architect by Patrick F. Cannon, with photographs by James Caulfield (Buy from University of Minnesota Press [US distributor for Glessner House] / from Amazon / from Bookshop)

Growing up in the suburbs of Chicago and spending most of my young life near home, trips into the city were very special. I looked forward to and savored those trips, be it with my family to see Cats or go to Taste of Chicago, spending the day at the Art Institute of Chicago on a school field trip, or going to neighborhoods outside of the Loop while taking a high school urban studies class. Many years before I decided to go to architecture school, I was able to visit Frank Lloyd Wright’s buildings in Oak Park, see Louis Sullivan’s Chicago Stock Exchange Trading Room at the Art Institute, and look at other places that make it seem like a future in architecture was preordained. When it came time for me to decide where to live after graduating from architecture school, there was no choice: it had to be Chicago. The last neighborhood I lived in before moving to New York City was Lincoln Square, home to German bars and restaurants, a bowling alley above a hardware store, and Louis Sullivan’s last ever commission, the facade for the Krause Music Store on Lincoln Avenue. Even though it was faster for me to walk down an alley to get to and from the “L,” I preferred to walk Lincoln instead, one reason being so I could pass Sullivan’s small facade and soak in its dense ornament.

Given the Krause Music Store’s location in Louis Sullivan’s timeline (it was completed in 1922, two years before his death), it is fittingly the last project in Louis Sullivan: An American Architect, an overview of Sullivan’s extant buildings published by Glessner House last month that features words by Patrick F. Cannon and photographs by James Caulfield. There are plenty of buildings on the life and architecture of Sullivan, who himself wrote a few books, but the focus on the buildings that remain, and their documentation through new photographs, feels like enough of a novel spin to warrant the book. After all, if there is any American architect whose fame rests in part on the shortsightedness of building owners who destroyed their creations, it is Louis Sullivan (Paul Rudolph is right there behind him), who had a number of masterpieces demolished in the 1960s and 70s, including the Stock Exchange and the Schiller Building (aka Garrick Theater). Ironically, both of these buildings still appear in An American Architect, given that the first building’s trading room was, as mentioned, moved to the Art Institute, and portions of the Schiller’s facade survive at the entrance to Second City in Old Town.

There is a lot to like about An American Architect. Although Krause showing up on one of the last spreads in the book may point to it being chronological, the book’s chapters are thematic, focusing on building types (houses, office buildings, banks, etc.) that nevertheless paint a vivid portrait of Sullivan’s 67-year life and four-decade-long career. Seeing similar building types together makes perfect sense, especially with the skyscrapers he is most famous for. The Auditorium Building, arguably his greatest work, is treated as such, given its own chapter, “The Wonder of the Age,” presented in depth across more than thirty pages of photographs. Unfortunately, the part of the book I don’t like is Caulfield’s style of photography. Although his photographs favorably depict buildings both famous and previously unfamiliar to me, and his access to interiors make the book literally revealing, his HDR(-esque?) technique results in images that tone down shadows sometimes to the point of non-existence; it’s a style I’m not a fan of, having made the same commentary with Cannon and Caulfield’s book on Wright’s Unity Temple last year. With An American Architect, the technique is most excusable when the photos zoom in on Sullivan’s facades to show every piece of the carefully crafted details.

Books Released This Week:

(In the United States, a curated list)

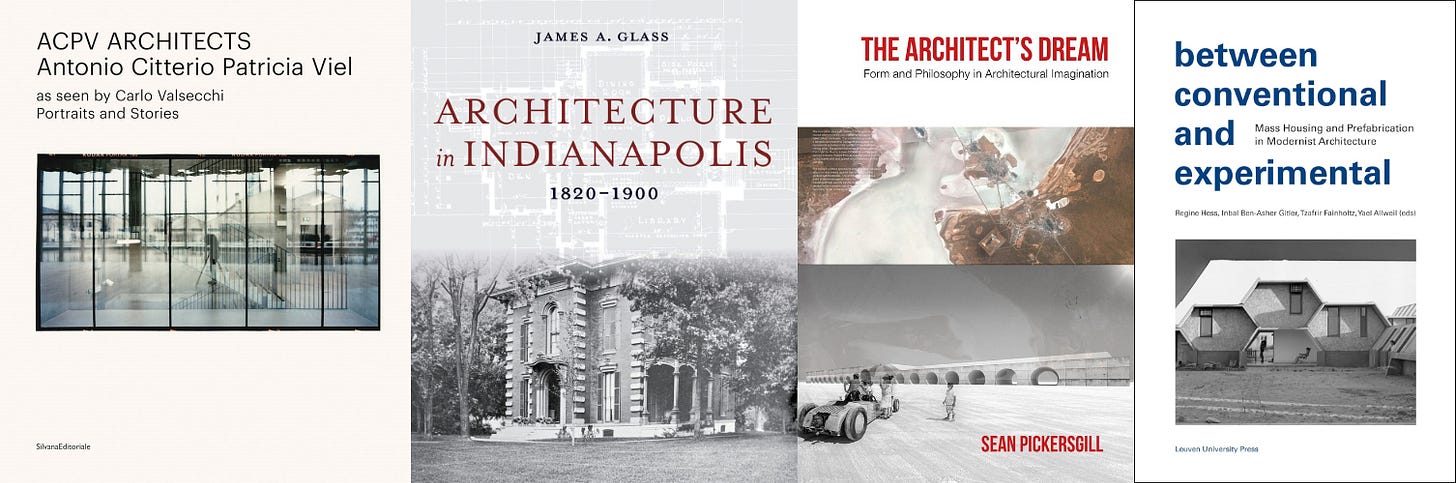

ACPV Architects Antonio Citterio Patricia Viel: As Seen by Carlo Valsecchi by Antonio Citterio, et. al. (Buy from Silvana Editoriale/DAP / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “This volume, which collects some of the Milan-based practice ACPV ARCHITECTS Antonio Citterio Patricia Viel’s main projects between 2000 and 2020, is drawn from an exhibition of ACPV buildings photographed by Carlo Valsecchi, held at the Palazzo Morando in Milan.”

Architecture in Indianapolis: 1820–1900 by James A. Glass (Buy from Indiana University Press / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “As a planned community, Indianapolis boasted finished frame and brick buildings from its beginning. […] Preservationist and architectural historian Dr. James Glass explores the rich variety of architecture that appeared during the city's first 80 years, to 1900.”

The Architect’s Dream: Form and Philosophy in Architectural Imagination by Sean Pickersgill (Buy from University of Chicago Press [US distributor for Intellect Ltd.] / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “A unique perspective on how to understand, and even create, meaningful architecture.”

Between Conventional and Experimental: Mass Housing and Prefabrication in Modernist Architecture edited by Regine Hess, et. al. (Buy from Cornell University Press[US distributor for Leuven University Press] / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “This book offers a comprehensive exploration of how both conventional and experimental prototypes and series [in mass housing and prefabrication] gave rise to an architecture for all…”

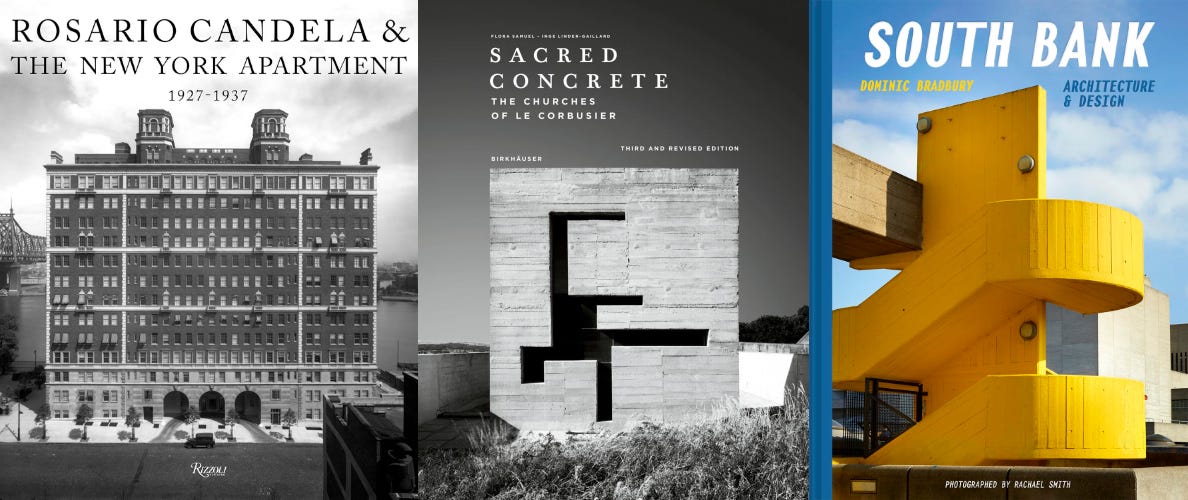

Rosario Candela & The New York Apartment: 1927-1937, The Architecture of the Age by David Netto, Paul Goldberger and Peter Pennoyer (Buy from Rizzoli / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Masterworks of the Jazz Age architect whose residential buildings are as significant in their impact on the character of New York as the skyscrapers of Wall Street.”

Sacred Concrete: The Churches of Le Corbusier by Flora Samuel and Inge Linder-Gaillard (Buy from Birkhäuser / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “The book explains Le Corbusier’s relationship with religion; it introduces his designs for La Sainte-Baume, the Chapel of Notre Dame du Haut de Ronchamp, La Tourette monastery, and the church of St. Pierre, and investigates his impact on the ensuing modern church architecture in Europe.”

South Bank: Architecture & Design by Dominic Bradbury, photographs by Rachel Smith (Buy from Batsford / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Architecture and design specialist Dominic Bradbury provides an unrivaled insight into the buildings that populate one of London’s epicenters of art and entertainment.”

Full disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, AbeBooks Affiliate, and Bookshop.org Affiliate, I earn commissions from qualifying purchases made via any relevant links above and below.

Book News:

Two tepid reviews of Materialized Space: The Architecture of Paul Rudolph at The Metropolitan Museum of Art: one by me at World-Architects and one by Jack Murphy at The Architect’s Newspaper. (If you can get past its paywall, Dallas Morning News has Mark Lamster’s negative review of the exhibition.)

Fabrizio Gallanti reviews Photo City: How Images Shape the Urban World at the V&A Dundee for Drawing Matter, describing it as “not a photographic exhibition, where only an endless procession of framed pictures would be on display, but a complex discourse, showcasing the influence and usages of other media for its dissemination…”

Verso’s 50-year commitment to radical publishing, which has included great books by the likes of Michael Sorkin, Eyal Weizman, Stephen Graham, Reinier de Graaf, Mike Davis, and others related to architecture and cities, is in jeopardy “after the bankruptcy of one its most trusted partners,” so they launched a Kickstarter.

From the Archives:

Companions to the two Books of the Week are two pairs of books that I reviewed on my blog, one pair related to mid-century modern architecture and one pair on Louis Sullivan:

Fans of mid-century modern architecture would be remiss not having the two Mid-Century Modern Architecture Travel Guide books written by Sam Lubell, photographed by Darren Bradley, and published by Phaidon: West Coast USA was released in 2016 and East Coast USA followed in 2018. (These links point to reviews of them on my blog.) Being a fan of any kind of architecture means seeing such buildings in person, and the two guides by Lubell and Bradley are excellent companions for driving trips to cities and states with a density of mid-century modern architecture. The West Coast book is most relevant in the case of this newsletter, given that half of the book’s buildings are in and around Los Angeles, and 90 minutes away is Palm Springs, which boasts the largest concentration of preserved mid-century modern architecture in the world. And there’s Covina Bowl, on page 206, “one of the (literally) largest temples to [Googie’s] energetic, bawdy design.” I’m not sure if the team plans to fill in the states between the coasts with future volumes, but Phaidon’s just released Atlas of Mid-Century Modern Masterpieces by Dominic Bradbury makes it seem doubtful. I hope they prove me wrong.

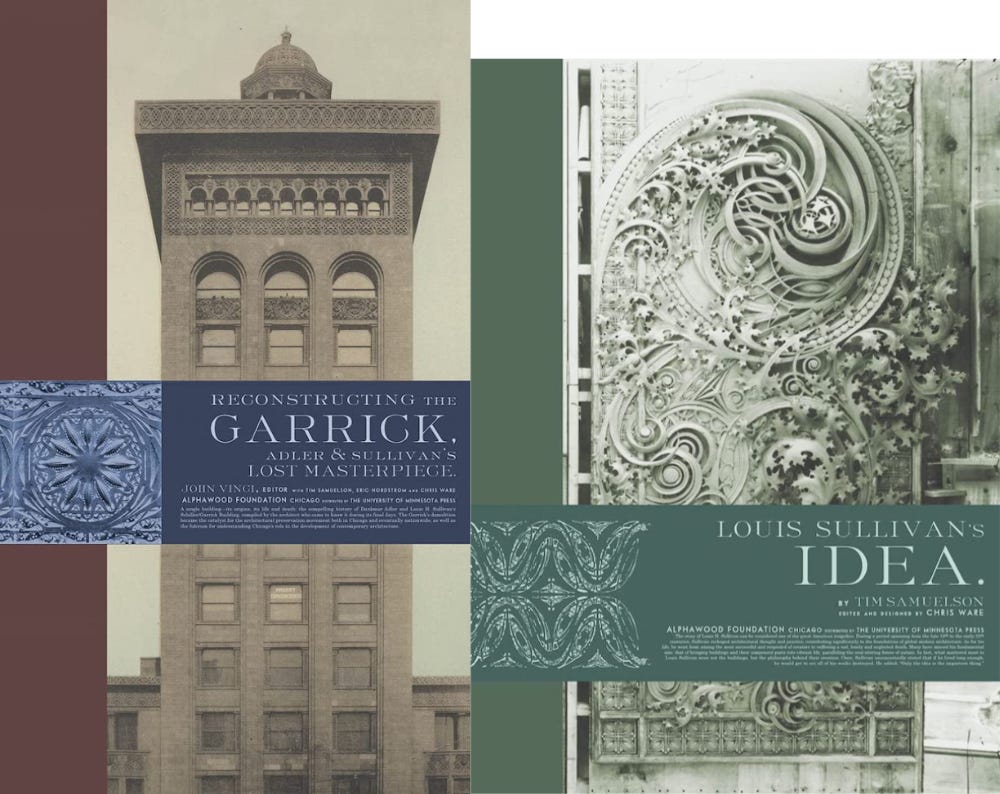

In late 2021 and early 2022, Wrightwood 659 displayed Romanticism to Ruin: Two Lost Works of Sullivan & Wright, which consisted of one exhibition on Louis Sullivan and one exhibition on Frank Lloyd Wright. The Sullivan exhibition, Reconstructing the Garrick: Adler & Sullivan’s Lost Masterpiece, was accompanied by a book of the same name published by Wrightwood 659’s Alphawood Foundation. A bonus for fans of Sullivan was Alphawood’s release of Louis Sullivan's Idea at the same time. Their matching constructions/productions, papers, and book designs (by Chris Ware) make them definite siblings, while the slightly different page sizes, color schemes, and placement of bandeleros, as illustrated in the cover images above, mean they are not quite twins. I reviewed the two books together in March 2022, after the exhibition had closed, calling Reconstructing the Garrick, edited by architect John Vinci with contributions by Tim Samuelson, Eric Nordstrom, and Chris Ware, “phenomenal,” and similarly praised Louis Sullivan's Idea, edited and written by Tim Samuelson, calling it “more of a scrapbook than an academic reference [… with] archival documents and images painting a portrait of Sullivan as vivid as Samuelson's words.” One treat in Louis Sullivan’s Idea, especially for me, is a poster with Sullivan’s working drawings for the facade of the Krause Music Store, his last commission. It didn’t take me long to frame it and hang it on my living room wall.

Thank you for subscribing to A Weekly Dose of Architecture Books. If you have any comments or questions, or if you have your own book that you want to see in this newsletter, please respond to this email, or comment below if you’re reading this online. All content is freely available, but paid subscriptions that enable this newsletter to continue are welcome — thank you!

— John Hill