This newsletter for the week of November 25 looks at a recently published monograph on Herzog & de Meuron, the Swiss practice that won the Pritzker Architecture Prize in 2001 and has realized hundreds of projects since their founding in 1978. An older book on Herzog & de Meuron is at the bottom of the newsletter, while in between are the usual new releases and headlines. Happy reading!

Book of the Week:

Twentyfive x Herzog & de Meuron by Stanislaus von Moos and Arthur Rüegg (Buy from Artbook/DAP [US distributor for Steidl] / from Amazon / from Bookshop)

The website of Herzog & de Meuron assigns a three digit number for every project, built or unbuilt. The 626 projects, as of today, span from “001 Attic Conversion” in 1978 — the same year Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron founded their firm — to the 2024 competition entry for “626 Grand Stade de Casablanca.” Such a large output, combined with their prolonged influence on younger generations of architects, makes a “complete works” series a given — something the duo has been doing with Gerhard Mack since the 1990s, with six chronological volumes published to date.

But what about a curated selection of their best and most important projects? Art historian Stanislaus von Moos and architect Arthur Rüegg contend that such “a critical evaluation of the oeuvre in its evolution up to the present” has been missing, with none “since the catalog book Herzog & de Meuron: Natural History edited by Philip Ursprung (2002).” (See the bottom of this newsletter for more on that earlier book.) Twentyfive x Herzog & de Meuron, as the name indicates, does just that: It critically presents 25 buildings designed by the Basel studio over its 46-year history. The 25 projects, to further quote from their preface, “identify the office’s most significant design strategies” and present them through “a targeted selection from the extensive image material” in the office’s archive.

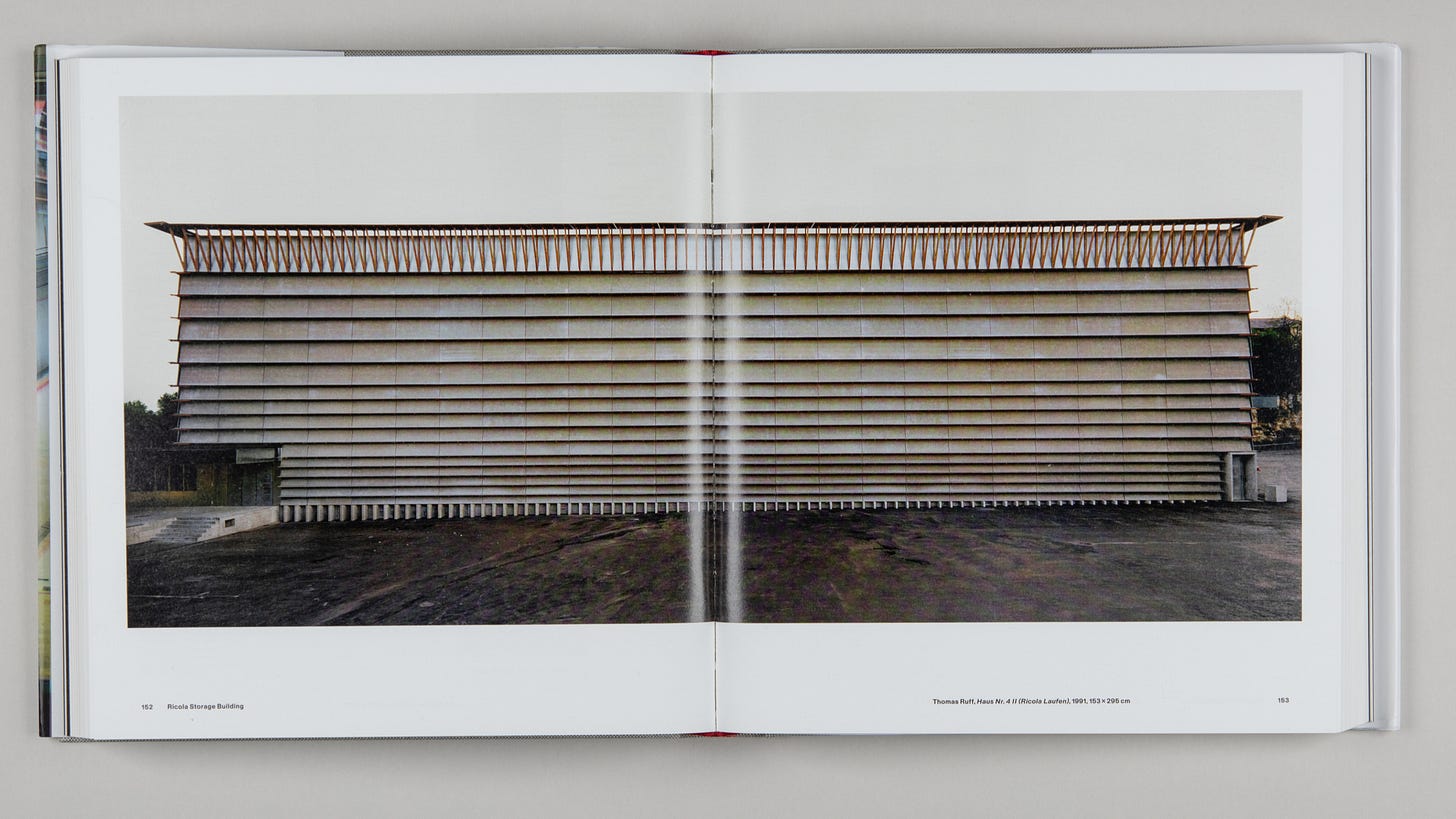

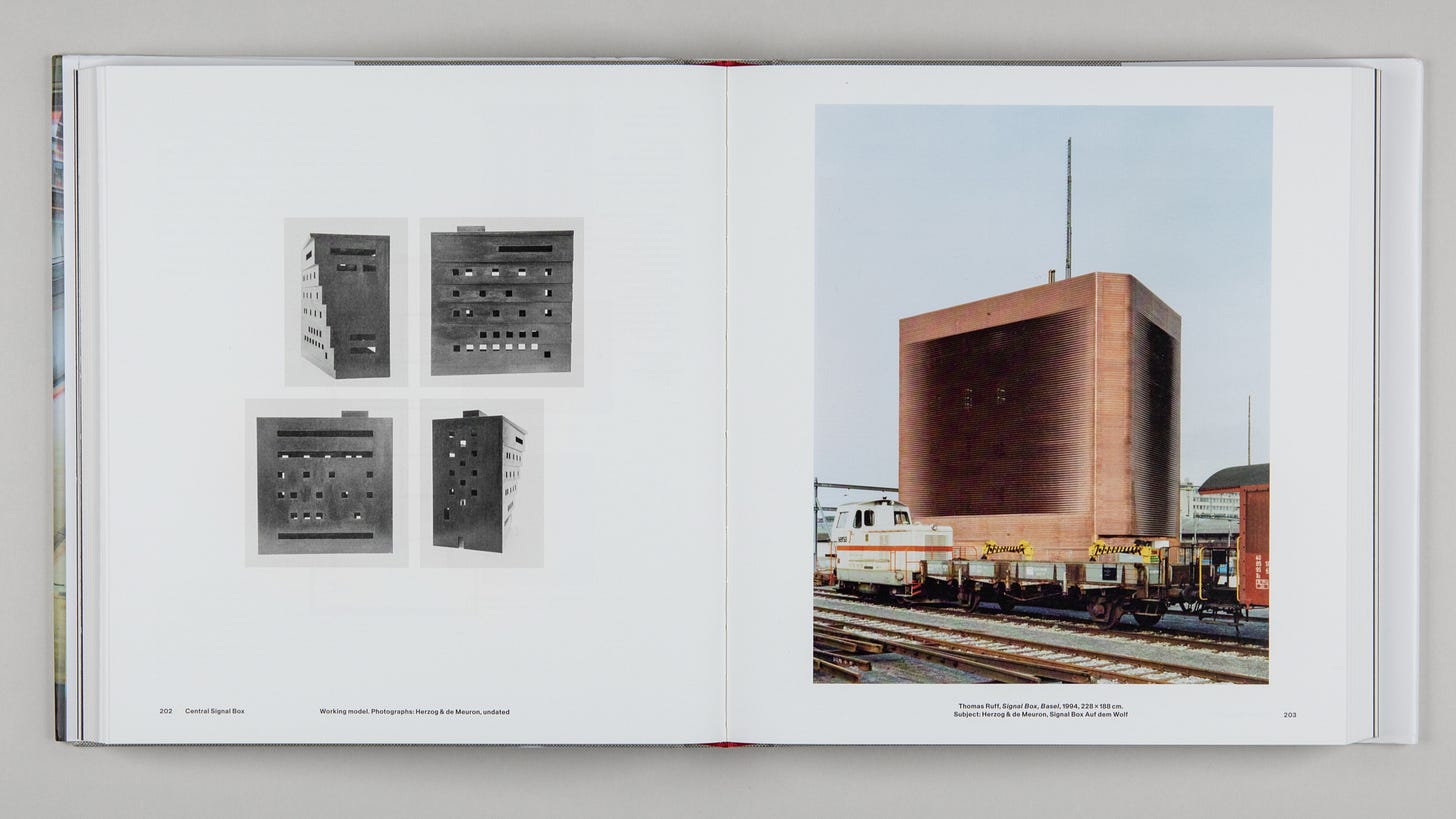

Naturally, the co-authored production includes introductory essays by both von Moos and Rüegg, but before readers come to those they are confronted with 55 photos taken by Pierre de Meuron, presented across 15 pages with black matte backgrounds. The photos of old and new buildings, cityscapes, and landscapes are, in my opinion, excellent; he has a sharp eye for interesting details and framing them for maximum impact. Later in the book, when photographs by Iwan Baan, Balthasar Burkhard, Thomas Ruff, Margherita Spiluttini, Wolfgang Tillmans, and Hannah Villiger take center stage with the 25 projects, de Meuron’s photographs make occasional appearances and, I’d say, fit in surprisingly well with the images by artists and professional photographers.

De Meuron’s photo spreads early in the book are bookended by postcards from Jacques Herzog’s archive: 84 of them, also on black matte pages. The postcards acted like a replacement for Herzog’s own eye (Rüegg explains that Herzog didn’t start taking photos until the arrival of the smartphone) and, loosely grouped on each page by geography or subject matter, exhibit wide-ranging interests, from traditional spaces and monumental structures to religious art and cemeteries. These sections at the beginning and end of the book are open to readers’ interpretations, and I take them as straightforward presentations of the founding partners’ interests and expressions of the way various parts of the world have influenced the projects they are known for.

The lengthy essays by von Moos (40 pages) and Rüegg (42 pages) look at the work of Herzog & de Meuron in the realms of, respectively, art and the built environment. Each one discusses or touches on some of the 25 works that follow (these are helpfully referenced to the project pages) but do not limit themselves to just those 25. So Rüegg, for example, goes into some depth on the Stadtcasino Basel (2012–2020), which is not one of the 25 works, but then uses that renovation project to examine the Park Avenue Armory (2006–) and CaixaForum (2001–2008), both of which appear later in the book but in his essay are considered as divergent expressions of how Herzog & de Meuron treat existing buildings. Put another way, the 25 works enable von Moos and Rüegg to critically appraise the individual buildings, but the introductory essays force them to make sense of the office’s wider 626-strong oeuvre. The latter is a daunting task that each author does very well.

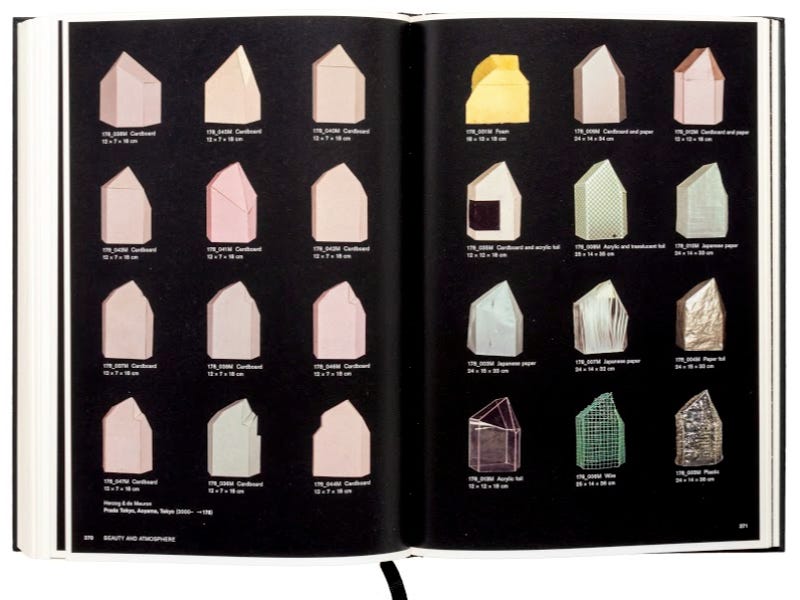

Of course, the bulk of the 480-page book is the 25 works, presented chronologically by start date, from Photographic Studio Frei (1981–1982) to Serpentine Gallery Pavilion (2011–2012). Ending the selection with a project completed a dozen years ago may seem odd, but there are handful of other projects that were completed in the interim, such as the Elbphilharmonie Hamburg (2001–2016). Still, there are basically no projects from the last seven years, indicative of von Moos and Rüegg’s idea for the book starting around fifteen years ago but also how “the office’s most significant design strategies” can be found in earlier decades, particularly the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s. Think of what you consider the most important Herzog & de Meuron project and most likely it’s here: Stone House (1982–1988), the two Ricola storage buildings (1986–1987, 1992–1993), Eberswalde Technical School Library (1994–1999), Central Signal Box in Basel (1994–1999), Tate Modern (1994–2000), Dominus Winery (1995–1998), and National Stadium Beijing (2002–2008) among them.

Texts for the works are handled by the authors, with their contributions noted accordingly; this approach is a refreshing alternative to the marketing copy found in too many monographs. Yet, given that von Moos and Rüegg opted not to interview Herzog, de Meuron, or other partners in the office for the book, references in the text come from books and other articles about the office and its projects, much of them pulled from the Complete Works written Gerhard Mack and a lot of it from German-language publications. These critical texts are accompanied by quality selections of drawings, photographs, and other illustrations. Ultimately, the whole is a big, beautiful package that befits one of the most important architectural practices of the last fifty years and foregrounds their best buildings.

Books Released This Week:

(In the United States, a curated list)

Arts & Architecture 1950–1954 (Buy from Taschen / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “The complete facsimile of the ambitious and groundbreaking Arts & Architecture was published by Taschen in 2008 as a limited edition. This new curation—directed and produced by Benedikt Taschen—brings together the magazine’s highlights from 1950 to 1954, with a special focus on mid-century American architecture and its luminary pioneers including Richard Neutra, Eero Saarinen, and Charles & Ray Eames.”

Best High-Rises 2024/25: Internationaler Hochhaus Preis / The International High-Rise Award (English/German) edited by Peter Körner and Peter Cachola Schmal (Buy from JOVIS / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Best High-Rises 2024/25 presents thirty-two of the most exciting recently completed high-rise projects that combine sustainability, external form, internal spatial qualities, and social aspects into exemplary designs that point the way to the future. Each of these projects is comprehensively presented with photos and plans.”

Brutalist Hong Kong Map: Guide to Brutalist Architecture in Hong Kong by X (Buy from Blue Crow Media / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Hong Kong’s hitherto unmapped collection of remarkable Brutalist architecture is compiled here in this timely guide. This bilingual, two-sided map features forty examples of Brutalism across Hong Kong, from the early 1960s to 1980s. Researched by Bob Pang, with photography by Kevin Mak.”

Designing Aspen: The Houses of Rowland+Broughton by John Rowland and Sarah Broughton (Buy from PA Press / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “In this luxurious and aspirational home design book, the founders of renowned Colorado firm Rowland+Broughton share a selection of their extraordinary residential projects, with Aspen and the Rocky Mountains as the dazzling backdrop.”

Modern Amsterdam Map: Guide to Modern Architecture in Amsterdam, The Netherlands (Buy from Blue Crow Media / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Amsterdam’s finest 20th century architecture, from functionalist housing to ambitious urban plans, is featured on this bilingual map, including an introduction by Rixt Woudstra and original photography by Loes van Duijvendij.”

The Nordic Home: Scandinavian Living, Interiors, and Design (Buy from gestalten / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Explore the ingenious adaptations and original concepts emerging from Nordic culture, as designers continue to redefine simplicity in surprising ways. Nordic Living delves into the essence of Scandinavian design, celebrating the foundational role of minimalism.”

Studio Ghibli: Architecture in Animation (Buy from VIZ Books / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Learn how the visionary animation studio brings its vibrant worlds to life through hundreds of pieces of concept art, sketches, and background paintings that illuminate the architectural inspirations of Studio Ghibli’s animated classics. “

Full disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, AbeBooks Affiliate, and Bookshop.org Affiliate, I earn commissions from qualifying purchases made via any relevant links above and below.

Book News:

“The Art and Angst of Architecture in Southern California”: Common Edge has an excerpt from Sam Hall Kaplan’s recently released An Urban Odyssey: A Critic’s Search for the Soul of Cities and Self (Academic Studies Press) in which the critic recounts his “awkward dance with [Frank] Gehry” in the 1980s.

Over at Untapped, Marianela D’Aprile reviews Hélène Binet (Lund Humphries), the recent monograph on the photographer who has captured buildings by Le Corbusier, Peter Zumthor, and others with her large-format analog camera. The book is the subject of the next New York Architecture + Design Book Club, on December 3, at Head Hi in Brooklyn.

Part 1 and Part 2 of Canadian Architect’s round-up of “this year's best books for Canadian architects and lovers of design.” I wager that some of the books will be appealing to architects in other countries too.

“Kim Förster Challenges the Accepted Mythology of the Insitute for Architecture and Urban Studies in New Book”: Patrick Templeton reviews Förster’s Building Institution: The Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies, New York 1967–1985 at Architectural Record. (A blind recommendation; I didn’t read as I’m planning on a review of my own soon.)

From the Archives:

Apropos of this week’s Book of the Week, Herzog & de Meuron: Natural History, edited by Philip Ursprung and published by the Canadian Centre for Architecture and Lars Müller Publishers in 2002, is one of the “100 influential and inspiring illustrated architecture books” I included in Buildings in Print (Prestel, 2021). Here is what I wrote about it:

Swiss architects Jacques Herzog (1950–) and Pierre de Meuron (1950–) were awarded the Pritzker Architecture Prize in 2001, the first time “architecture’s Nobel” was given to a duo rather than an individual architect. The Basel-born architects formed their firm in 1978 and in the subsequent twenty-plus years their practice grew from designing small houses in Switzerland and Italy to the transformation of the huge Bankside power plant in London into the Tate Modern.

One year after the Pritzker, Herzog & de Meuron: Archaeology of the Mind opened at the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA), the Montreal institution founded by Phyllis Lambert the year after the Swiss architects opened their practice. Beyond its exhibitions, the CCA is known for its extensive archive of modern and contemporary architectural works. A perfect parallel happened with Archaeology of the Mind, which unpacked the seemingly bottomless archive of Herzog & de Meuron, displaying it alongside artworks and other artifacts that inspired the duo.

The exhibition was guest curated by Philip Ursprung (1963–), who also edited the companion catalog subtitled Natural History, which alternates glossy portfolios on dark backgrounds with essays and interviews on heavy matte pages across six thematic chapters. He limited the architects’ drawings and models to sketches and study models: no plans, no models made for clients, no commissioned photographs of completed buildings. Exhibition and book describe process over product and, combined with the inspirational objects, reveal Herzog & de Meuron’s unique process and their artistically informed temperaments.

Thank you for subscribing to A Weekly Dose of Architecture Books. If you have any comments or questions, or if you have your own book that you want to see in this newsletter, please respond to this email, or comment below if you’re reading this online. All content is freely available, but paid subscriptions that enable this newsletter to continue are welcome — thank you!

— John Hill