Architecture Books – Week 6/2025

Architecture, Not Architecture: Diller Scofidio + Renfro's new 7-pound "portable archive"

This newsletter for the week of February 3 looks at two books by Diller Scofidio + Renfro, both elaborate productions: “Book of the Week” is Architecture, Not Architecture, published this week by Phaidon, and the book “From the Archive” is the 12-year-old Lincoln Center Inside Out: An Architectural Account. In between are the usual headlines and new releases. Happy reading!

Book of the Week:

Architecture, Not Architecture by Diller Scofidio + Renfro (Buy from Phaidon / from Amazon / from Bookshop)

If I had to determine just one defining characteristic of the work of Diller Scofidio + Renfro, it would be a questioning of conventions and disciplinary boundaries. One of the first projects designed by Elizabeth Diller and Ricardo Scofidio when they formed their eponymous practice in 1981 was a house that looked like a house: the Kinney (Plywood) House was built on the remains of a burned-down house in New York’s Westchester County, with conventional windows set into unconventional plywood walls; the firm calls it “an uncanny ghost” of the site’s former occupant. The rest of the 1980s would see the married architects carrying out numerous projects, none of them architecture: art installations, theater sets, performance art. It wasn’t until the end of the decade that Diller + Scofidio gained another architectural commission, the much lauded, un-house-like Slow House, which broke ground in 1991 but was never finished due to the client’s finances. Their next building, Slither Housing in Gifu, Japan, was completed in 2000 — nineteen years after their first building.

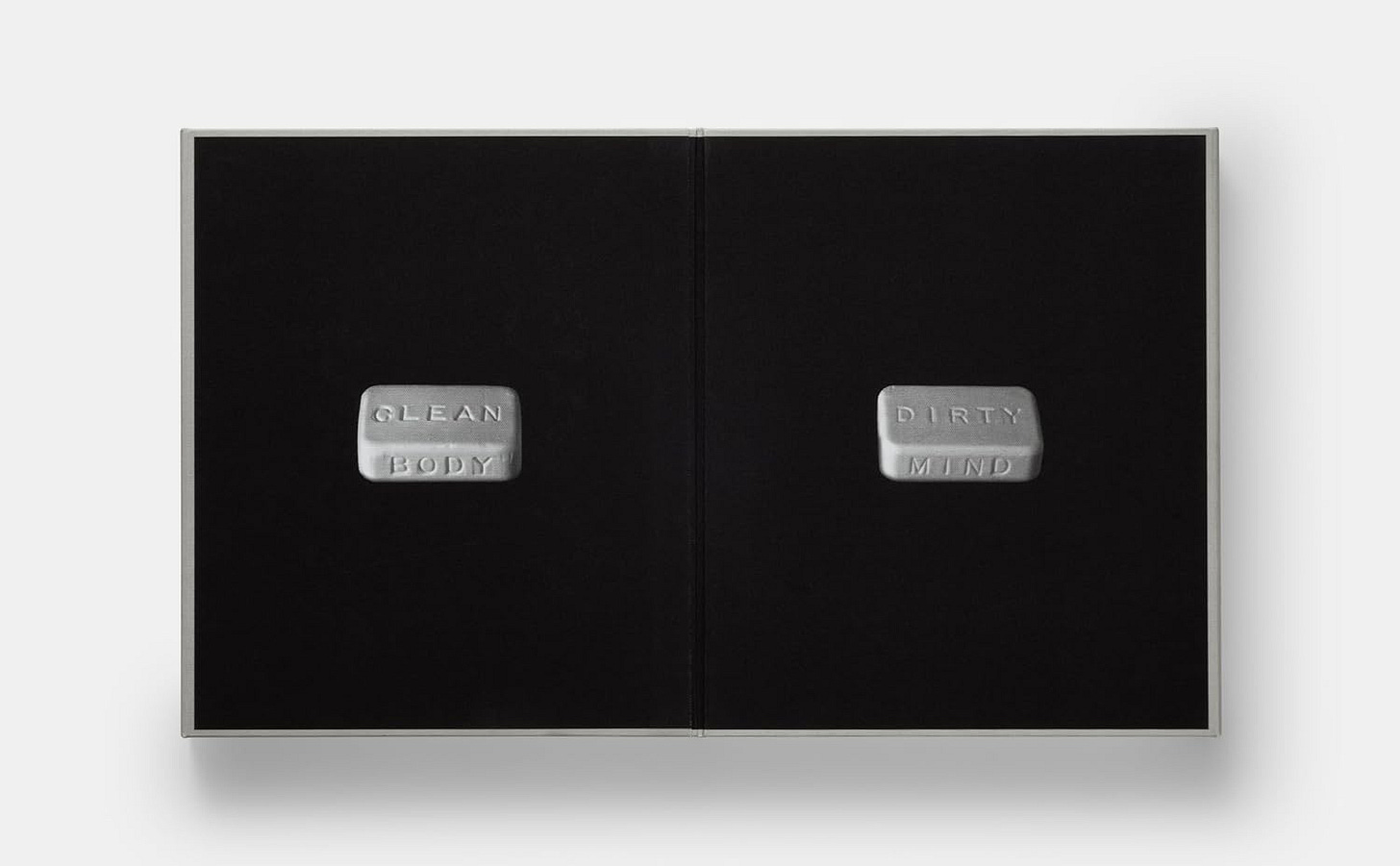

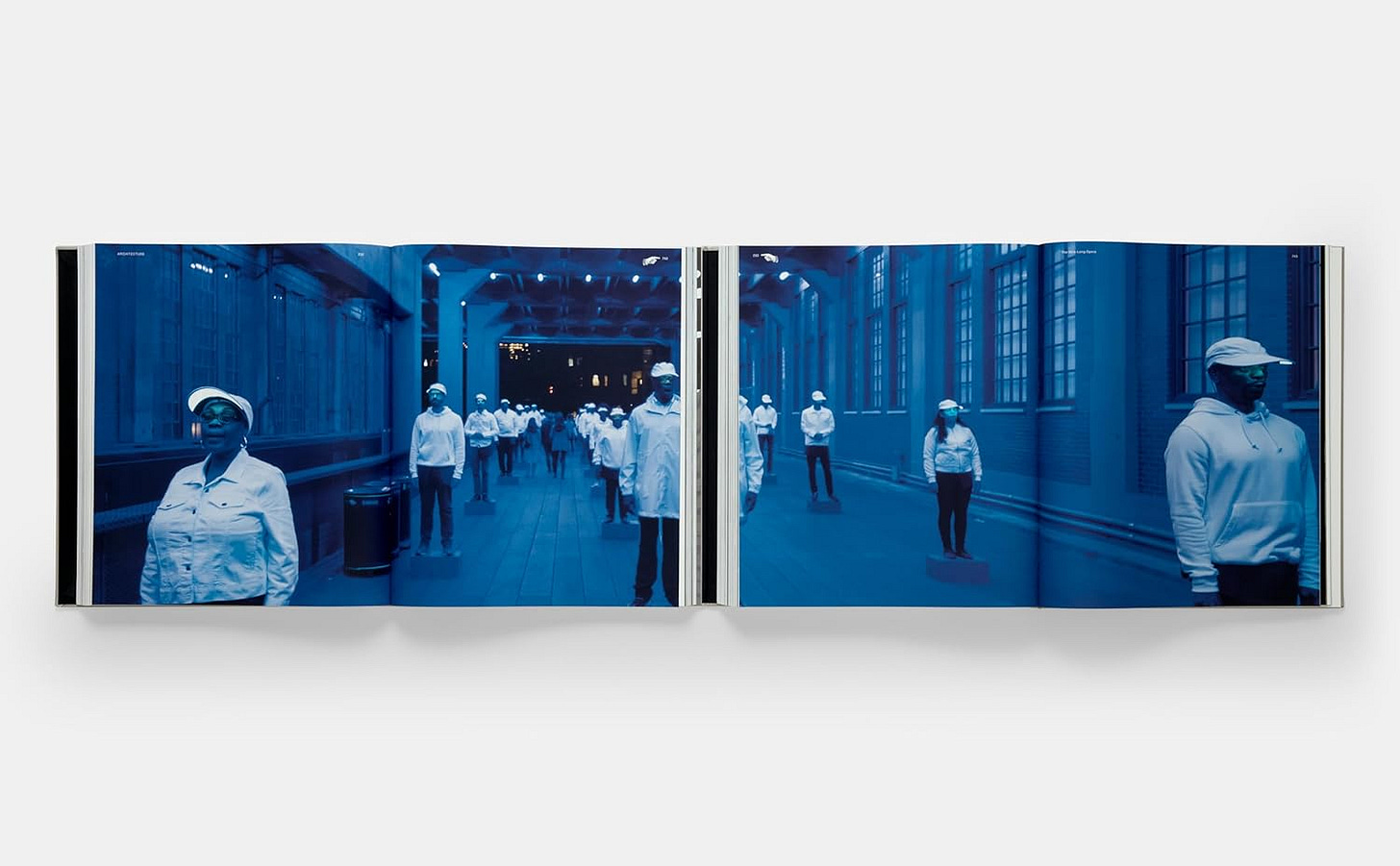

The gaps between these architectural works are apparent in the first few-dozen pages of Architecture, Not Architecture, described as a “portable archive of the studio’s work” from 1981 to 2024 — more than 40 years that neatly straddle the firm being renamed Diller Scofidio + Renfro in 2004, when Charles Renfro was made partner. (DS+R has four partners now, with Benjamin Gilmartin made one in 2015.) The book, released this week by Phaidon, presents 128 of the studio’s built, unbuilt, and in-progress projects in chronological order, separating them literally into two volumes: Architecture (pages 1–392) and Not Architecture (pages 393–792). The two “books” are mounted on linen covers that snake back and forth — a bit like another much lauded unbuilt project, Eyebeam Museum — and allow the two parts to be read side-by-side when fully open. A novel construction, yes, but it begs the question: Why does a practice that questions conventions and disciplinary boundaries organize their projects via those same conventions/boundaries?

Acknowledging this conundrum, DS+R writes this in the short “Note to Reader” on page five: “While this brutal bisection of our body of work is unnatural to the studio’s cross-disciplinary ethos, the separation reveals the contamination between projects made within the constraints of the profession and those created outside of its norms.” The “contamination” is made explicit through a hand symbol that appears in the corner of certain pages and directs readers to open the other volume to a specific page; when looking at the book spread out on a table, these matching spreads create what could be called mega-spreads, as at bottom. With a page size of approximately 10x12”, one needs nearly four square feet of table space to look at Architecture, Not Architecture in this manner, but the hefty construction and a strong magnet holding the two volumes together enable the book(s) to be read closed/stacked as well. Like the index on the DS+R website, a “Tables of Content” lists the projects in alphabetical order, by typology, and by “obsession” — a list that includes “crime,” “edibles,” “robots,” and other terms fans of DS+R should grasp — allowing the book(s) to be read in other ways besides chronological order.

Billing the book as a “portable archive of the studio’s work” raises another question: How does this book relate to the digital archive that is their website? When I compared some of the early projects in the Architecture volume to the firm’s website, the overlap was very close, with the text for Slow House matching exactly and the selection of images being basically the same. Ditto Slither, The Brasserie, Viewing Platform, even the Blur Building. Disappointment set in, but only briefly, until I noticed that the images for the Blur Building (in both Architecture and Not Architecture) are much more numerous than on the DS+R website. Furthermore, a baker’s dozen selection of “Dialogues” (with Laurie Anderson, Alan Cumming, Sylvia Lavin, Hans Ulrich Obrist, etc.) that inserted here and there between the projects add content not found in the studio’s digital archive; and later projects, such as the many parts comprising the transformation of the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, have words and images that are more in-depth in print than on the web. There are even projects, such as a secretive penthouse on Fifth Avenue, that are in the book but not on the website — not there yet, as I’m assuming the effort of making this book occupied the time that would have been spent updating the website, and now with the book published it is just a matter of time before the website’s content is more closely aligned with that of the book.

Returning to DS+R’s questioning of conventions and disciplinary boundaries, the same approach can be found in the books they have produced. Two earlier books that found DS+R rethinking a book’s contents and its construction are focused on two projects mentioned above: Blur Building and Lincoln Center. Instead of telling the story of the former retrospectively, through the usual commissioned texts found in case studies, Blur: The Making of Nothing (Abrams, 2002) compiled faxes, office correspondences, shop drawings, newspaper clippings, and other documents that were contemporaneous with the process of designing and realizing the pavilion at the 2002 Swiss Expo. DS+R managed to take the things thrown away or boxed up and forgotten to strongly convey the struggles involved in making the unconventional, mist-covered building. Lincoln Center Inside Out: An Architectural Account (Damiani, 2013; see also the bottom of this newsletter) describes the many parts of their transformation of Lincoln Center via dozens of gatefolds, with full-bleed photographs on the outside embracing “back stories” on the designs of the same spaces inside. Architecture, Not Architecture finds DS+R going beyond these books to meld content and construction: using the conjoined volumes and keyed “contaminations” to provide a panoramic portrait of a studio with one of the most diverse and influential architectural and non-architectural portfolios over the last half-century.

Books Released This Week:

(In the United States, a curated list)

Adaptable Cities and Temporary Urbanisms, by Lauren Andres (Buy from Columbia University Press / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “This book examines temporary urbanisms across varied global contexts, considering their significance for cities and everyday life as well as for policy and practice.”

The Delos Symposia and Doxiadis, edited by Mantha Zarmakoupi and Simon Richards (Buy from Lars Müller Publishers / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Spearheaded by members of the digital humanities Delos Project, The Delos Symposia offers a contemporary critical reassessment of the extravagant conferences choreographed around Greek architect Constantinos Doxiadis and his ‘science of human settlements’ known as ‘Ekistics.’”

Sustainable and Regenerative Materials for Architecture: A Sourcebook, by Will McLean and Pete Silver (Buy from Laurence King Publishing / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “There is a creative explosion of work taking place in architecture and design schools exploring materials such as mycelium, clay/earth, engineered timber, bio-based plastics and algae. This handbook of low- and no-carbon materials for architects and designers focuses on sustainable materials, their sourcing, technical properties and the processes required for their use in architecture.”

Transcalar Prospects in Climate Crisis: Architectural Research in Re/action, edited by Jeffrey Huang, Dieter Dietz, Laura Trazic and Korinna Zinovia Weber (Buy from Lars Müller Publishers / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Transcalar Prospects in Climate Crisis offers a vital compilation of research projects and essays reflecting the investigative efforts at EPFL Architecture, [addressing] critical issues like material uses, land and soil degradation, environmental justice and circular urban flows…”

Full disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, AbeBooks Affiliate, and Bookshop.org Affiliate, I earn commissions from qualifying purchases made via any relevant links above and below.

Book News:

Over at Canadian Architect, Graham Livesey reviews Alberto Pérez-Gómez's An Alliterative Lexicon of Architectural Memories, a two-book, apparently self-published series structured like a dictionary but focused on meaning in architecture.

“New book explores China’s Belt and Road Initiative from the ground level” at KU News, the new book being New Silk Road: The Architecture of the Belt and Road Initiative, an analysis of massive infrastructure projects built by China beyond its borders. It was written by Michele Bonino, Francesca Governa, and others, and published this month by Birkhäuser.

Barret Havens shares the results of an Association of Architecture School Librarians (AASL) survey aimed at finding publishers of architecture books that are “highly useful” for students in schools of architecture. (Thanks to Seth W. for the heads up!)

Over at STIR World, Aarthi Mohan reviews the latest book by photographer Paul Tulett, Brutalist Japan (Prestel, 20204), which "challenges Brutalism’s harsh stereotypes, revealing the diverse and resilient nature of the style in Japan."

From the Archives:

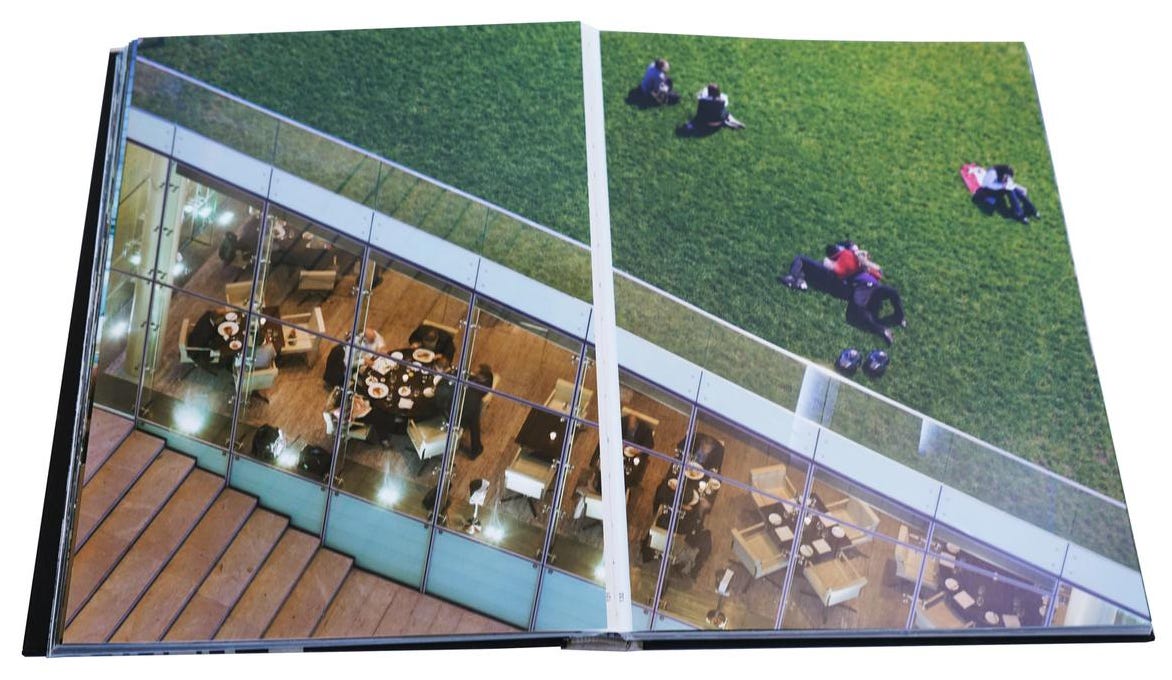

A previous Diller Scofidio + Renfro book with a similar size and ambition to Architecture, Not Architecture is Lincoln Center Inside Out: An Architectural Account, published by Damiani in 2013. The 311-page book has full-bleed photographs by Iwan Baan and Matthew Monteith on large, roughly 9x12” pages, and sixty gatefolds that make it occupy three square feet on a table when fully open. I liked the book so much I included it in the “Monographs (Buildings)” chapter of my 2021 book Buildings in Print: 100 Influential & Inspiring Illustrated Architecture Books. Around the time of its release I attended two events in which the architects celebrated the book and the project it documents, the ten-year transformation of Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts. Following a talk at the New York Public Library in April 2013 was a panel discussion at the Center for Architecture in May; I wrote a recap of the latter on my blog, where I also reviewed the book. Below are reworked, relevant excerpts from that post.

Lincoln Center Inside Out is a narrative of the physical transformation of Lincoln Center, told by the architects but incorporating the myriad players into the story. (The last spread in the book is actually DS+R's "Chart of Accountability," which puts them in the middle but acknowledges the roles of every entity involved in the project.) In the most direct sense, the book tells one story in two ways (a mini-Rashomon): one through the photos and one through the gatefolds. The former is like a cursory glance at the place, akin to scanning a publication or website, while the latter is much more immersive and informative, due to the great amounts of text, drawings, and other images that lie within.

Appropriately these gatefolds remind me of Scanning: The Aberrant Architectures of Diller + Scofidio, published by the Whitney as a companion to an exhibition of the same name, in which many images are hidden but can be partly glimpsed through cuts in the perforated end pages. Readers can see the images in their entirety, but revealing them means defacing the book by tearing along the perforations (I've yet to do that to my copy). Lincoln Center Inside Out is not as much of a tease, but it does reconsider what a book can be through its gatefold structure. This unique approach results in an extremely rewarding book but one that made for difficulties in bookmaking; the first printing actually "did not hold," according to Diller in her talk.

The book's arrangement happens to be both geographical and (reverse) chronological, a condition that happens due to the lack of a master plan with the project, and therefore the construction of one piece after another. As Diller described it, the "project evolved in a very organic way," where smaller ideas were executed with a shared language. In my Guide to Contemporary New York City Architecture, I describe that shared language as "peeling," but Diller defined it as a "double function" found in all parts of the project: the roof of the restaurant is also a bucolic lawn, the third-floor extension of Juilliard is also a ground-floor public space, and so forth.

After some oral histories covering Lincoln Center's inception and campus plan, the book moves onto a chapter on the bigger picture of transforming Lincoln Center, highlighted by a slideshow recounting DS+R's interview process. The chapters that follow focus on the Columbus Avenue Entrance, the North Plaza, the Street of the Arts, Julliard School, Alice Tully Hall, and the School of American Ballet, in that order.

The best parts of the book are definitely the gatefolds, as most of them are self-contained narrative details about the project. As Dimendberg noted, reading one gatefold each night before bed is a good way of taking in the book. The contents of each gatefold are unique, but in general they describe how some aspect of the project came into being and then document it in fine detail. For example, the gatefold devoted to the LED steps at Columbus Avenue addresses the oft-heard question of "How do I get to Lincoln Center?" (even as people were standing across the street from it, per the text), then delves into how the risers are detailed and how the lighting runs work. The most gatefolds are devoted to Alice Tully Hall, what Diller described as a project in its own right.

Not every piece of architecture deserves such a thorough and elaborate treatment, but it is definitely appropriate for Lincoln Center, given the scale and complexity of the undertaking, the modernist canvas on which the changes took place, and DS+R's creativity in making the place inviting to the public. Of course, it would not be enough for DS+R to publish just another book on a project, hence the innovative gatefold structure. In revealing what was hidden inside the guise of a coffee table book, Lincoln Center Inside Out parallels the project's double function, making it a joy to discover the changes that have take place over the last decade.

Thank you for subscribing to A Weekly Dose of Architecture Books. If you have any comments or questions, or if you have your own book that you want to see in this newsletter, please respond to this email, or comment below if you’re reading this online. All content is freely available, but paid subscriptions that enable this newsletter to continue are welcome — thank you!

— John Hill