This week’s newsletter focuses on protest architecture, the subject of a recently published book and exhibition, and a couple old books/journals of relevance. There’s also the usual newly released books and some headlines related to architecture books.

Book of the Week:

Protest Architecture: Barricades, Camps, Spatial Tactics 1830–2023 edited by Oliver Elser, Anna-Maria Mayerhofer, Sebastian Hackenschmidt, Jennifer Dyck, Lilli Hollein and Peter Cachola Schmal, published by Park Books (Buy from Amazon / Bookshop)

On numerous occasions I’ve written that the famous aphorism “you can’t judge a book by it’s cover” does not apply to architecture books. Fiction, yes, and a good deal of non-fiction, too, but many architecture books use the visuals on covers to encapsulate their contents to the extent that some accurate value judgments can be made from them. Protest Architecture is an exhibition organized by DAM and MAK (it was on display at DAM until January and is currently on view at MAK), and for the companion book the curators/editors opted forva lexical structure, something they chose to explicitly express on the cover: "The research into the topic of protest architecture produced an intricately ramified field of interconnected references, which led to the decision to structure this publication as a lexicon."

Furthermore, the cover clearly indicates the bilingual nature of the book, and it articulates the “connecting links” (italicized terms with arrows) that point readers to different entries that are found easily via the alphabetical organization of the book’s 528 pages. The only element not illustrated on the front cover is photography, which the book has in abundance: aerial and on-the-ground views of tent cities and other forms of protest architecture spanning nearly two hundred years. But readers need only flip the book over to see one such tent-city aerial, in a color photograph bleeding from the back cover to the thick spine. With these words and image on the outside of the book, readers should have formed some expectations and become prepared to navigate the book’s interior.

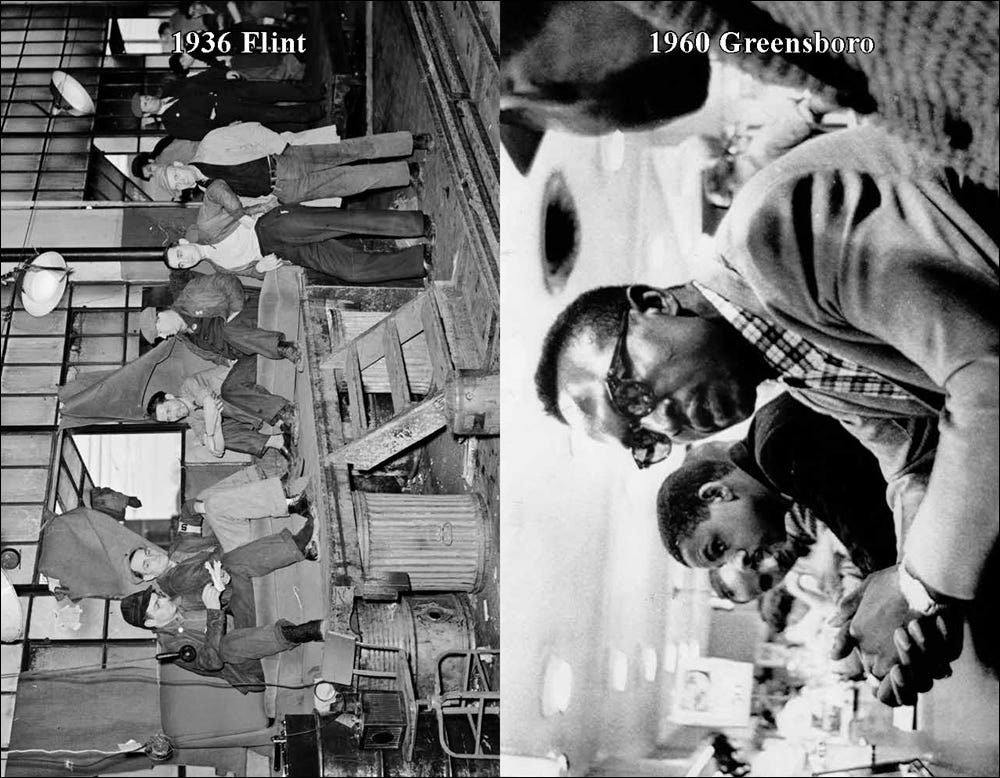

Before reaching the alphabetical terms, which extend from Abschütten to Zwentendorf (half the book’s contents are in German, remember), the book’s first 80 pages retrace a chronological history of protests and their temporary architectures, from 1830 to 2022. This section is presented in numerous chunks of a half-dozen images, all full-bleed and most of them turned 90 degrees, followed by a page of captions, in German and English. These brief texts reference entries in the a-to-z lexicon, with at least one describing the protest in more detail and others pointing to terms that are integral to the architectural aspects of protests, such as barricades, bricks, cobblestones, and even fire. Thirteen of the lexical entries serve as lengthy, multipage case studies, complete with drawings and and other in-line illustrations and more full-bleed photographs. The case studies include the Hong Kong protests, Occupy Wall Street, and Tahir Square.

While I find the architectural nature of protests questionable, since many of the temporary structures are haphazard collections of off-the-shelf materials and assemblies that are used as needed, making them more building than architecture, our current age embraces just about any physical conurbation as “architecture,” meaning so-called protest architecture is as valid a subject for an exhibition and book as is a famous architect or other traditionally architectural subject. Given that the organizers hail from Germany and Austria, the decision to release a bilingual book is logical, as is — literally — the lexicon format. At times, though, the bilingual aspect of the book makes for challenging reading, as do the numerous references inserted in the entries, often in the middle of sentences.

The two-century timeline at the start of the book puts the German and English text one after the other for each caption, but the rest of the book puts the entries in alphabetical order regardless of language. So, for instance, the English equivalent of the German term Baumhaus is Tree house, while other terms in the two languages abut each other, as in Barrikade and Barricade. In and of itself this is not an issue, since most readers will read one or the other language, but in some places, such as in the case studies, English readers need to flip back or ahead to the German entry to see the drawings; they might even read the case study not knowing to do so and miss out on the drawings. And occasionally, as in Bibliography, the same readers are pointed to a single entry, Literaturverzeichnis, to scroll the lengthy list of primarily German-language references. So, ultimately, the decision to adopt a lexicon format — a decision important enough to articulate it on the cover — makes the book a highly informative reference, but the bilingual format and numerous cross references make it a slog to read. Clearly a book for learning, not for leisure.

Books Released This Week:

(In the United States, a curated list)

architect, verb. : The New Language of Building by Reinier de Graaf, published by Verso (Buy from Amazon / Bookshop) — The OMA partner’s latest book, which I reviewed at World-Architects a year ago, is now in paperback.

The Home Office Reimagined : Spaces to Think, Reflect, Work, Dream, and Wonder by Oscar Riera Ojeda and James Moore McCown, published by Rizzoli (Buy from Amazon / Bookshop) — So far the most lasting impact of the pandemic has been working from home, making this book surveying home offices a logical one — and especially inspiring for people with the land and budget to create standalone studies like the one on the cover.

Tadao Ando: Spirit: Places for Meditation and Worship by Philip Jodidio, published by Rizzoli (Buy from Amazon / Bookshop) — Prolific author Philip Jodidio has written a few books on Tadao Ando (this XXL edition is one of my favorites), and his latest focuses on the churches, temples, and spaces of meditation that the Japanese architect excels at.

To the Ends of the Earth: A Grand Tour for the 21st Century by Richard Weller, published by Birkhäuser (Buy from Amazon / Bookshop) — A selection of 120 places that range in scale from buildings (Apple Park) to cities (Auroville) to regions (USA-Mexico border wall) are expressed in drawings and texts to be “understood as metaphors of contemporary global culture.”

Full disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, AbeBooks Affiliate, and Bookshop.org Affiliate, I earn commissions from qualifying purchases made via any relevant links above and below.

Book News:

Architecture-book clickbait! The Daily Mail spotted Brad Pitt “carrying a stack of architecture books and sipping on a healthy La Croix as he stopped to chat with fans.” I know Pitt likes architecture, but I only see one book (above) and can’t tell that it is, in fact, an architecture book…can you?

Over at BD, Charles Holland, formerly of FAT, “enjoys the latest volume in the series on Lutyens’ key works.” (I reviewed the first volume on my blog last October.)

In "Frampton's Calligraphy: Three Inflection Points," A/V’s Luis Fernández-Galiano ruminates on the influential writings of Kenneth Frampton, especially Modern Architecture: A Critical History, "Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance," and Studies in Tectonic Culture.

From the Archives:

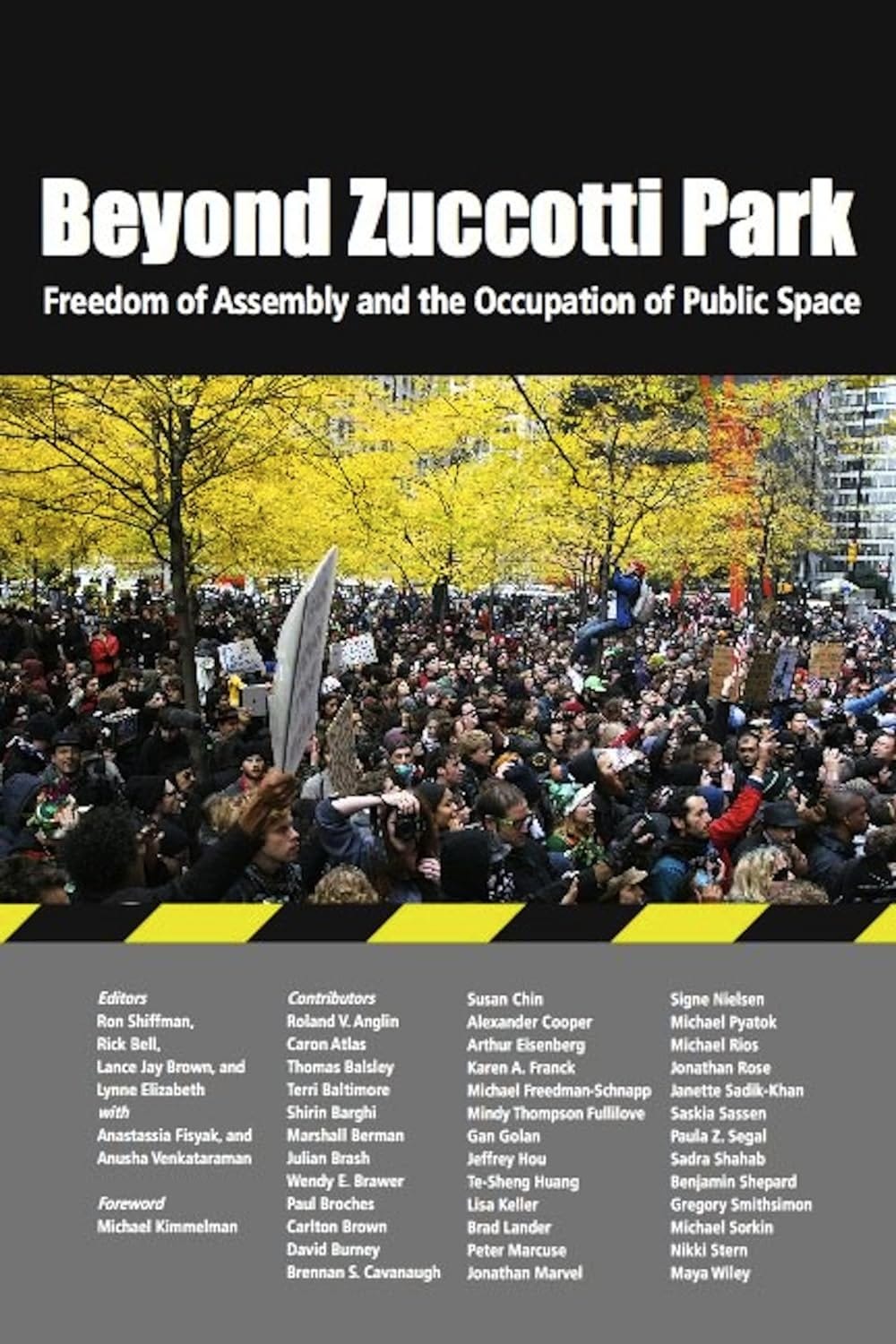

This week in 2013 I reviewed Beyond Zuccotti Park: Freedom of Assembly and the Occupation of Public Space, a book that, as its title indicates, is about the impact of Occupy Wall Street and the thinking about assembly and public space that it sparked. I wrote that the many contributors (look at that list on the cover!) provided “takes on public space and assembly [that] could be read as recipes for making urban open spaces amenable for exercising democratic rights. […] Consensus won't be found in the varied collection, but like OWS itself, there is a shared dissatisfaction with things, in this case how the public fits into public space.”

Apropos of the “Book of the Week,” protest is at the heart of CriticalProductive, the “biannual journal of architecture, urbanism, and cultural theory” edited by Milton S.F. Curry, at least in the first issue, V1.1: Theoretic Action, published in 2011. A few of the issue’s contributions look back to 1968, the year of global social protests, while one of the long features, “Highway Beautiful” by Richard M. Sommer and Glenn Forley, delves into the Selma to Montgomery voting rights marches that took place in 1965. Other long pieces include a transcript of a conversation between William F. Buckley, Jr. and Black Panther cofounder Huey P. Newton and Curry’s conversation with designer Lance Wyman about the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City. Although the first issue came out back in 2011 and the second issue, V2.1: Post-Capitalist City?, followed in 2013, the journal took a long, ten-year hiatus before last year’s announcement that Curry was restarting the project with MIT Press. Hopefully the next issue will come out soon and the subsequent issues will be published regularly: three times a year, as planned.

Thank you for subscribing to A Weekly Dose of Architecture Books. If you have any comments or questions, or if you have your own book that you want to see in this newsletter, please respond to this email, or comment below if you’re reading this online. All content is freely available, but paid subscriptions that enable this newsletter to continue are welcome — thank you!

— John Hill