This newsletter for the week of April 21 looks at a collection of unpublished writings by Colin Rowe, the influential historian and educator who died in 1999 at the age of 79. The collection, I Almost Forgot, was edited by Daniel Naegele, who a few years earlier edited a collection of Rowe’s letters. That previous book is at the bottom of the newsletter, alongside Rowe’s three antemortem As I Was Saying books. In between are the usual headlines and new releases. Happy reading!

Book of the Week:

I Almost Forgot: Unpublished Colin Rowe, edited by Daniel Naegele with Zhengyang Hua (Buy from The MIT Press / from Amazon / from Bookshop)

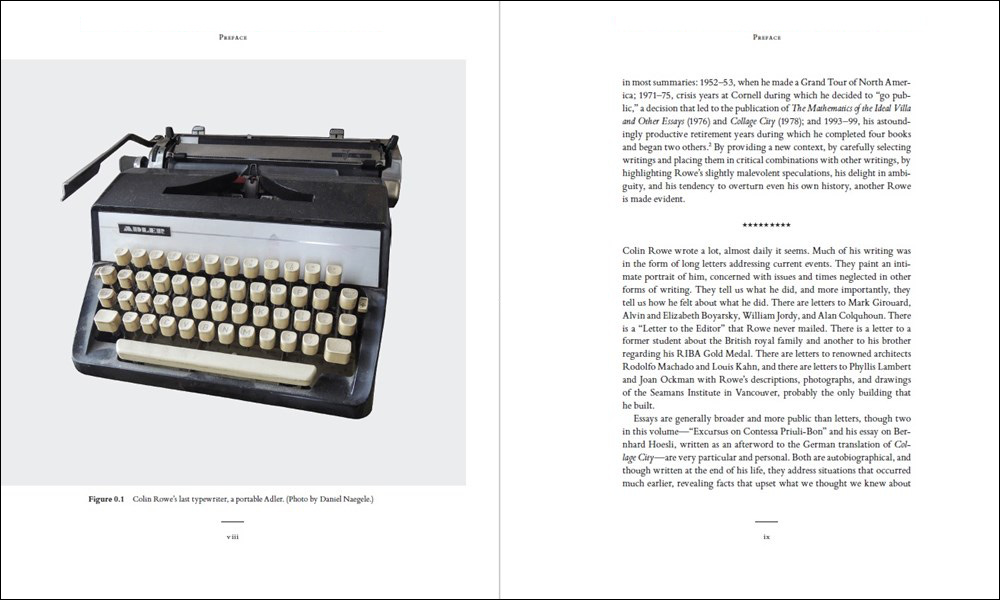

The first page of I Almost Forgot, architect Daniel Naegele’s second collection of historian and educator Colin Rowe’s words (the first collection is at the bottom of this newsletter) features a photograph of a portable Adler, Rowe’s last typewriter. It is an apt image to preface the 23 letters, lectures, and unpublished essays, not only because it is personal, autobiographical, but because it explains the formatting of what follows, particularly the frequent underlining. Rowe would also take notes by hand, but typewriting was his main means of putting words to paper, and it was the most legible means for people like Naegele interested in making archival documents public. Born in 1920, Rowe came of age when typewriters were abundant, and he was most likely set in his ways when word processors entered the mainstream in the 1980s. With italics impossible on a typewriter, be it for titles or for effect, underlining was the norm—and Rowe underlined a fair amount, much of it preserved by Naegele and his co-editor Zhengyang Hua in the transcriptions collected here.

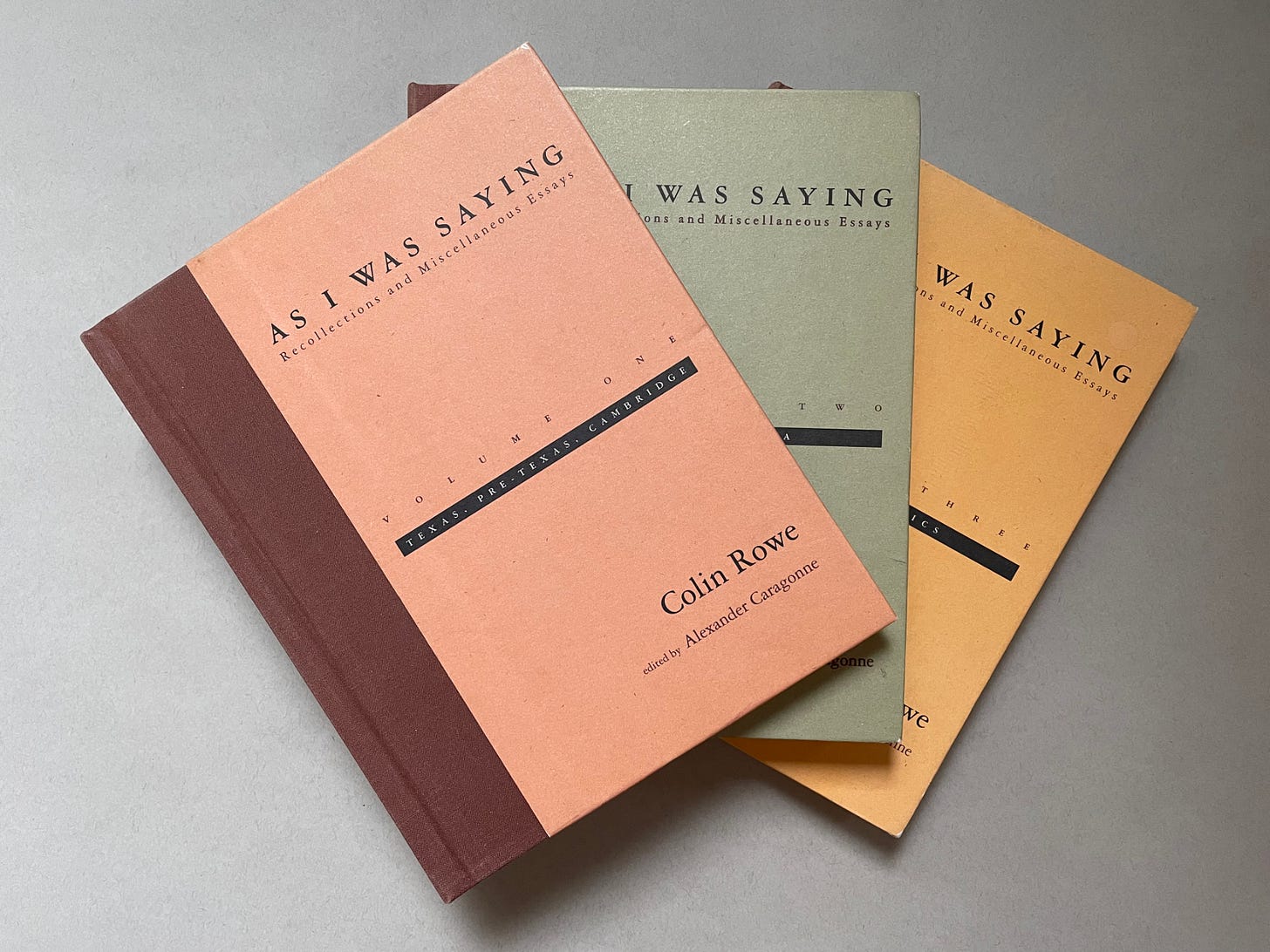

Before the unpublished letters, essays, and lectures were released by MIT Press in early 2023—in a size and hardcover format that fits nicely alongside the same publisher’s three volumes of Rowe’s As I Was Saying: Recollections and Miscellaneous Essays from 1995 (see bottom)—Naegele and Hua started a blog, In Memory of Colin Rowe, that was timed to the centenary of Rowe’s birth. I’m a fan of blogs (for good reason), but I’ve come to realize that print is a better archive than bits and bytes, even though the storage and sharing of digital files has made enormous strides since the days of Zip drives, CD-ROMs, and other obsolete devices; and given the timeframe of Rowe’s life (he died in 1999), it seems fitting to compile his words put to paper on paper. (Given his penchant for underlining, print makes more sense than screen, given that underlining in the latter signals links.) Simply put, I Almost Forgot is an archive of Rowe’s words not previously published (with a few exceptions), but as Naegele asserts in his introduction, it fills in the gaps other collections did not address and it “[paints] a lighter, more casual portrait of the erudite, witty, always self-amused scholar.” Thankfully, Naegele and Hua also provide extensive notes, elucidating Rowe’s shorthand and now-obscure references, and pointing readers to the previously published collections of Rowe’s words.

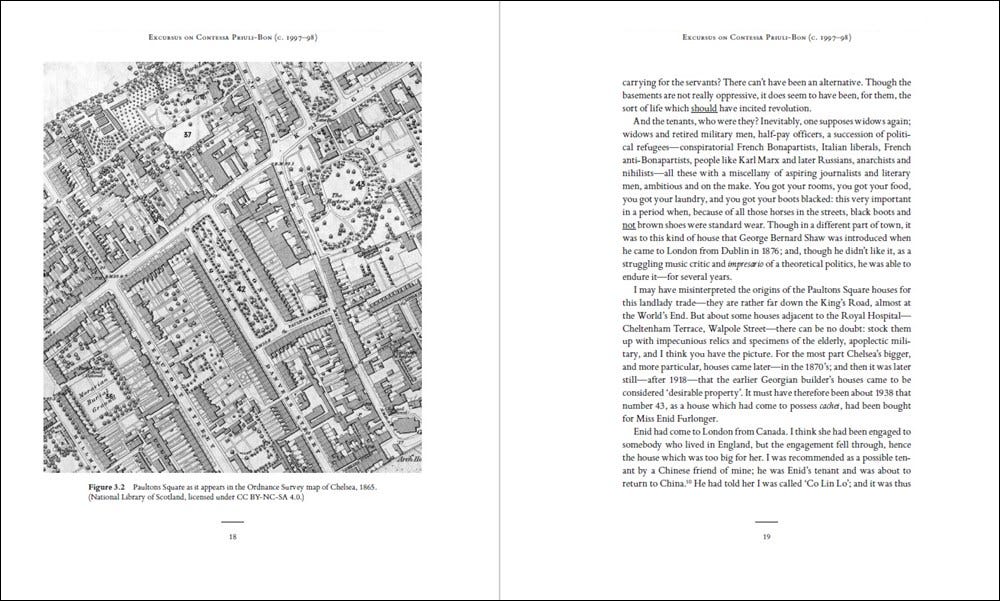

I Almost Forgot also reveals how Rowe’s writing style changed over the course of roughly four decades, though it does not do this directly by arranging the 23 pieces in chronological order. Instead, Naegele and Hua put everything in chronological order by subject—by whom or what Rowe was talking about in the letter, essay, or talk. It’s a curious arrangement that puts an unsigned, undated, and unaddressed letter to the editor first because it quoted W. H. Auden’s New Year’s Letter, first published in 1941, at length. The second piece includes two letters to Mark Girouard from 1972, in which Rowe discusses his education right before WWII. It is followed by an essay from 1997/98 on Contessa Priuli-Bon, who “serves as an aide-mémoire through which he looks back to his life in London during the mid-1940s,” per the editors introduction to the essay. And so forth. Even though Rowe’s “published writings can be heavy and difficult, yet his lectures, letters, and talks were almost always casual [and] humorous,” per Naegele, this is not a breezy cover-to-cover read. As such, the editors’ intros are particularly helpful in foregrounding Rowe’s timeline and helping readers determine which pieces they want to tackle through the brief synopses.

Even though the book is chronological by subject rather than by date of the writing or talk, the last eight pieces in the book were all done in the last half of the 1990s, in the years leading up to Rowe’s death in 1999 at the age of 79. Rowe wrote every day of his life, and the years after his retirement from Cornell University in 1990 were no different. Some highlights from the last third of the book—they are actually highlights from the whole book, I think—include: a 1996 letter to his brother David, in which Colin analyzes the recipients (and omissions) of the RIBA Royal Gold Medal, prompted by the one he received the year before; a 1996 lecture about furniture that begins with a conversation between Rowe and Philip Johnson critiquing “these repro French jobs we’re sitting in” as well as Mies’s Barcelona chair; and a lengthy talk he gave at ETH Zurich in 1997 about, per the editors, “the fallacy both of modern architecture’s no-history history and the theory of modern architecture that relied on it.” The last piece, like the first, is undated, but also unfinished, so Naegele and Hua assume “The Existential Predicament,” as it was titled, was the first part of a longer piece he was working on when he died. It is a fitting ending to a behind-the-scenes collection capturing Rowe’s habitual outpouring of words and the way they helped shape his thinking about architecture.

Books Released This Week:

(In the United States, a curated list)

The Architecture of the Wire: Infrastructures of Telecommunication, by Carlotta Daro (Buy from The MIT Press / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “The Architecture of the Wire explores the development of telecommunications infrastructure and its impact on the architectural and urban culture of the modern age—from poles, wires, and cables, to ‘micro-architectures,’ such as the théâtrophone and the telephone booth.”

Landscape Fieldwork: How Engaging the World Can Change Design, by Gareth Doherty (Buy from University of Virginia Press / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — This book “provide[s] tools for practitioners to engage more deeply with multidimensional, diverse landscapes and the communities that create, live in, and use them.”

Going for Zero: Decarbonizing the Built Environment on the Path to Our Urban Future, by Carl Elefante (Buy from Island Press / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “[S]easoned architect and former AIA president Carl Elefante addresses how buildings and cities can and must help resolve the looming climate emergency. Elefante offers a decidedly alternative viewpoint, one informed by his architecture career rescuing buildings from senseless demolition and learning from the practices and wisdom embedded in built heritage.”

The Pocket Universal Principles of Architecture: 100 Architectural Archetypes, Methods, Conditions, Relationships, and Imaginaries, by WAI Architecture Think Tank, Nathalie Frankowski and Cruz Garcia (Buy from Quarto/Rockport / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “The Pocket Universal Principles of Architecture is a convenient and portable reference for students, practitioners, and educators who seek to broaden and improve their understanding of and expertise in architecture.”

Full disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, AbeBooks Affiliate, and Bookshop.org Affiliate, I earn commissions from qualifying purchases made via any relevant links above and below.

Book News:

Harvard Magazine profiles the “poignant children’s books” of Ann Kim Ha, a graduate of Harvard GSD and a co-owner, with her husband, of an architectural design studio in New Jersey.

Colossal features some photographs from Ukrainian Modernism (FUEL), the first book by Kyiv-based photographer and researcher Dmytro Soloviov.

Wallpaper* peees inside Casa Mexicana, a new book by Wallpaper* editor Jonathan Bell and photographer Edmund Sumner.

STIR World looks at the contributions to Architecture After War: A Reader, published last year by MACK and CANactions.

From the Archives:

Although books under his name are few, just a half dozen, Colin Rowe’s voluminous output of words led to the compilation of three volumes of “essays, memoranda, disjecta membra, and memorabilia for the most part unpublished” in his lifetime. As I Was Saying: Recollections and Miscellaneous Essays, edited by Alexander Caragonne, was published by MIT Press in hardcover in 1995 (the year of his Royal Gold Medal, with the paperbacks following in 1999, the year he died) as Volume One: Texas, Pre-Texas, Cambridge, Volume Two: Cornelliana, and Volume Three: Urbanistics. Their subtitles indicate a primarily chronological and pedagogical structure, with the first roughly spanning the 1950s and his teachings at University of Texas Austin and Cambridge University, the second starting in 1962 with his decades-long tenure at Cornell University, and the third focusing on urban design, both through essays and student work in the graduate program of the Urban Design Studio at Cornell. Each volume has between 15 and 20 pieces, ranging from five-page letters and ten-page book reviews (most of the latter in the first volume) to lengthy essays and even longer lectures that approach 70 pages, with images and formatted to the consistent page size of the three volumes. Is it worth owning all three issues? Architects drawn to “Transparency,” his influential essay written with Robert Slutzky, will want the first volume; those enamored with his teaching at Cornell will no doubt want the second volume; and fans of Collage City should opt for volume three. Of course, hardcore fans of Rowe’s entire output probably own all three volumes already.

The Letters of Colin Rowe: Five Decades of Correspondence, edited by Daniel Naegele, was published by Artifice Press in 2018. I reviewed it on my blog in early 2020, writing in part:

If you would have told me years ago that eventually I'd be reading through nearly 600 pages of letters written by architectural historian Colin Rowe and liking it, I would have vehemently denied it. I'll admit he wrote two of the most important architecture books of the second half of the twentieth century—Collage City with Fred Koetter and the essays compiled in The Mathematics of the Ideal Villa and Other Essays—but his writing is very demanding; his words are important but they are hardly enjoyable. Obviously there's a difference between scholarly writing for academic journals and books aimed at architects and architectural students, on the one hand, and correspondences between people, both professionally and personally, on the other -- therein lies the qualities of The Letters of Colin Rowe. […] The book reveals a lot about Rowe (a lot more than I'm guessing he ever would have made public), but one thing in particular comes across to me: writing was his life. His printed output was not prolific, but his letter-writing surely was—or at least it seems that way in this era of email and social media. The Letters of Colin Rowe is a nice respite to another time and a rewarding peek into the mind of a great thinker.

Thank you for subscribing to A Weekly Dose of Architecture Books. If you have any comments or questions, or if you have your own book that you want to see in this newsletter, please respond to this email, or comment below if you’re reading this online. All content is freely available, but paid subscriptions that enable this newsletter to continue are welcome — thank you!

— John Hill