This newsletter for the week of May 19 features a catalog from the Venice Architecture Biennale, where I was last week. It so happens to be the companion for the national pavilion that the international jury gave a Golden Lion. Both pavilion and publication are highly rewarding, in my opinion. The catalog prompted me to consider my past hauls from past Biennales, at bottom, while in between are new releases and headlines, the latter longer than usual given last week’s hiatus. Happy reading!

Book of the Week:

Heatwave: The National Pavilion of the Kingdom of Bahrain, edited by Andrea Faraguna, with contributions by Maryam Al Jomairi, Latifa Al Khayat, Eduardo Gascón Alvarez, Caitline Mueller, Leslie Norford, Wafa Al Ghatam, Paris Bezanis, Maitham Al Mubarak, Mohammed Salim, Eman Ali, Alexander Puzrin, Jonathan Brearly, Viola Zhang, and Office for Applied Histories (Abdulla Janahi and Laila Al Shaikh)

Last week's blip in the weekly rhythm of this newsletter arose from me being in Italy for the Venice Architecture Biennale. In my duties as editor at World-Architects I wrote an overview of the main exhibition, Intelligens: Natural. Artificial. Collective., curated by Carlo Ratti, and will be highlighting more pieces of the Biennale in the coming weeks. Previous Biennales found me taking home the hefty official catalog and as many publications from the national pavilions as my luggage would allow (see bottom for some of those past hauls). This time I was determined to undo this tendency, and in the end I brought home just the official catalog—indispensable for research and reference—and one book from one pavilion: Heatwave, the companion to Bahrain’s Golden Lion-winning national pavilion.*

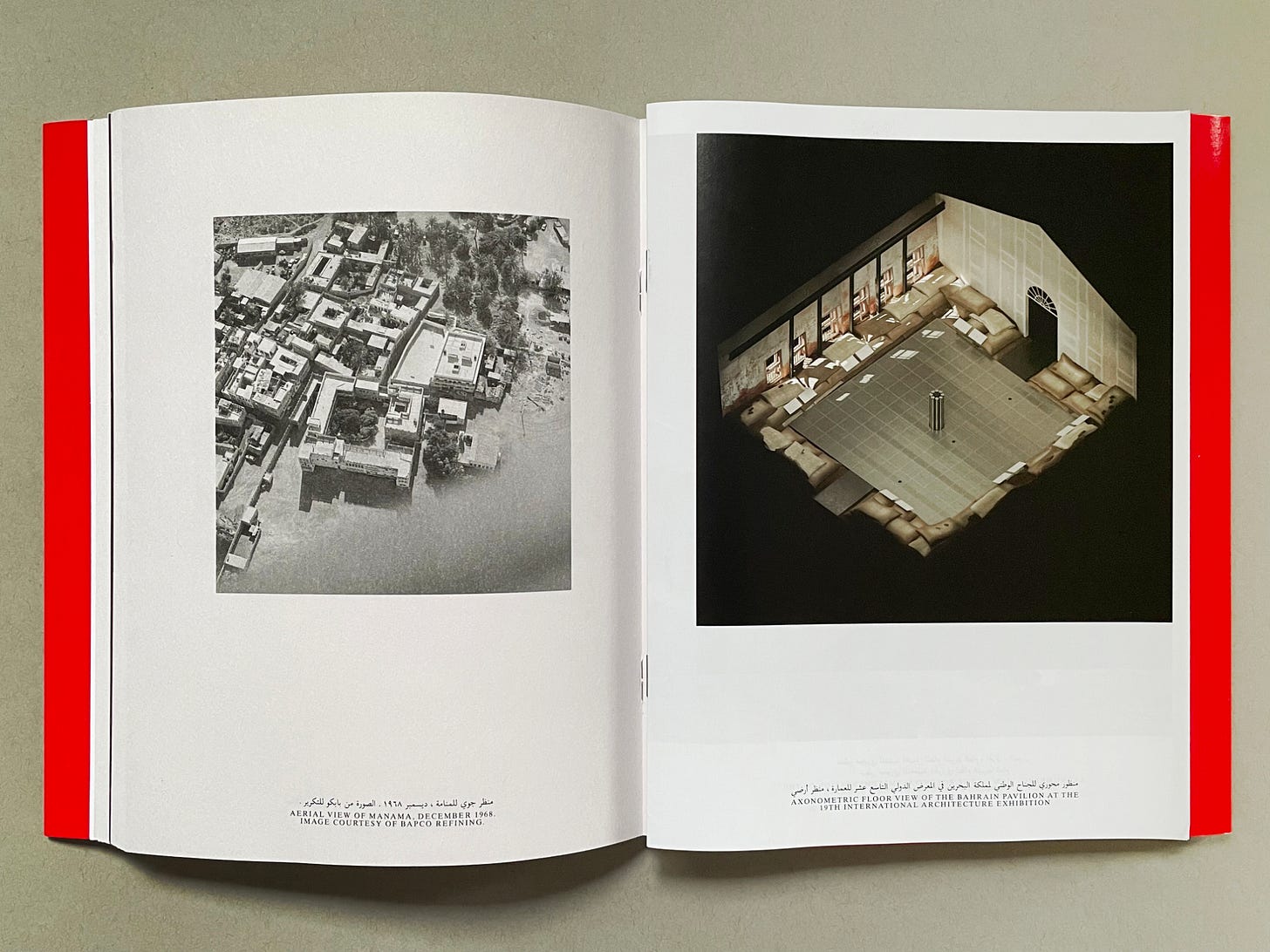

Bahrain is one of roughly a dozen national pavilions tucked enfilade-like into the Artiglierie, a long building set perpendicular to the longer, considerably more famous Corderie, which has served as a main venue for the alternating art and architecture Biennales ever since Paolo Portoghesi lined it with the Strada Novissima in 1980. Both buildings are part of the larger Arsenale, the former home of Venice’s shipbuilding industry. The spaces are impressive but they come with restrictions that curators and contributors have to contend with. Heatwave, curated and designed by architect Andrea Faraguna**, fits a prototype for an outdoor shading/cooling structure into one bay of the Artiglierie. Visitors step into a low-ceilinged space rung by large sandbags and lit by perimeter lighting. Beneath the cantilevered ceiling, supported by a central drum and a few subsidiary columns, are some explanatory displays and a few stacks of books with bold red covers, free for the taking. With just a few elements, the pavilion makes a strong impression and is instantly memorable.

The book is also impressive and memorable. Like most exhibition publications, the companion catalog to the Bahrain Pavilion comes with statements from the commissioner (Khalifa Bin Ahmed Al Khalifa, president of the Bahrain Authority for Culture and Antiquities, and deputy commissioner Noura Al Sayeh-Holtrop), a statement from the curator, and numerous textual and visual essays that provide context and reasoning for the exhibit. The name itself says as much: Heatwave alludes to planetary warming and the fact Bahrain, a small island nation on the Persian Gulf, the world’s hottest body of water, has been subject to intense heat for a long time and will be affected by rising waters in the future. Or as pavilion curator and designer Faraguna puts it simply in his essay, “Heatwave is an architectural experiment that addresses the global rise of temperatures. [… The] project introduces a unique cooling design for public spaces that adapts to local conditions while reducing carbon emissions.”

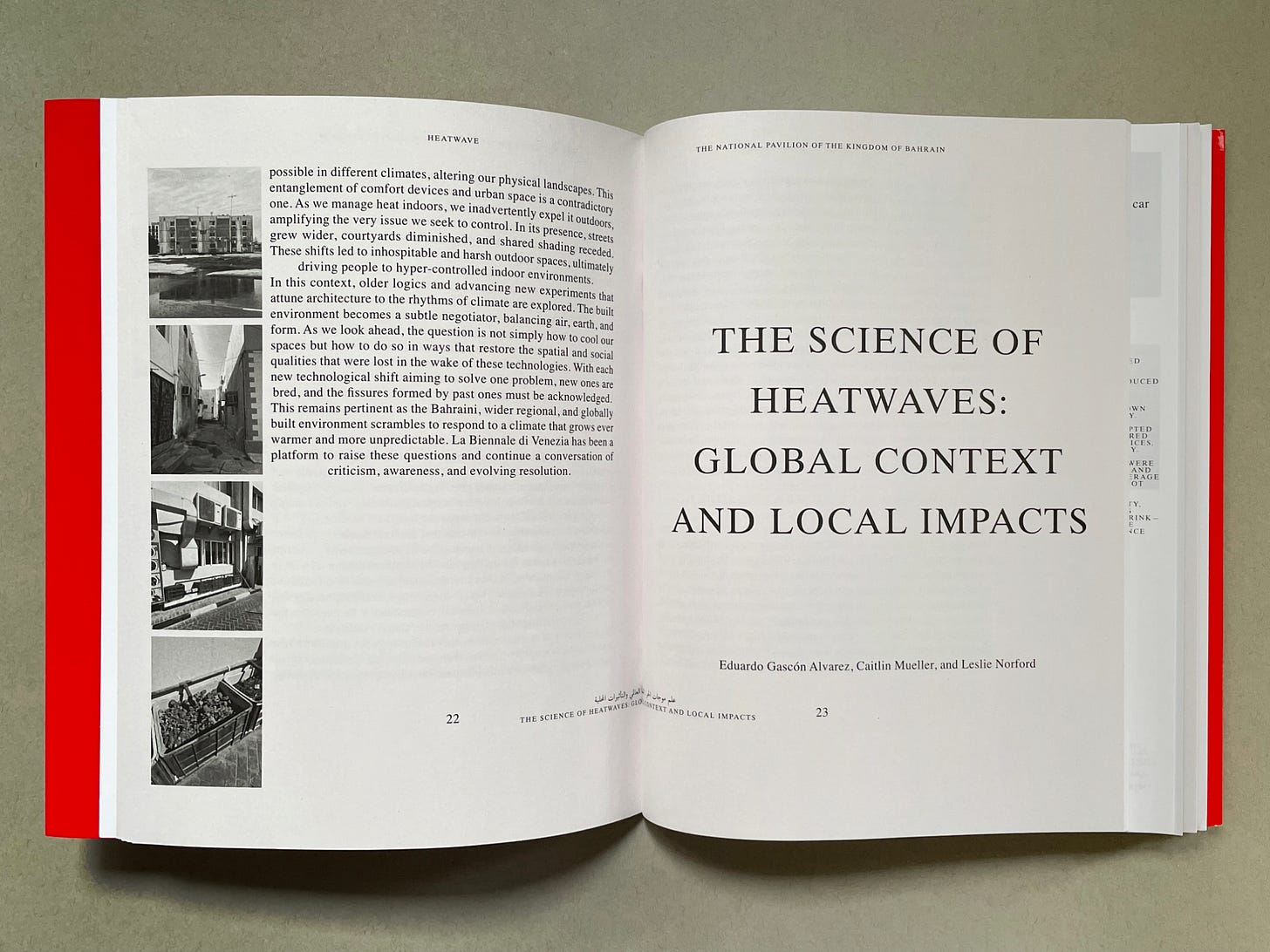

Why such a cooling structure is needed should be obvious to most, but it acknowledges at least a few things: not everyone can find relief from intense heat in air-conditioned spaces; a reliance on interiors cooled by ACs can leave people in dangerous situations during power outages, especially those caused by peak cooling demand on hot days; and an overuse of air conditioners is exacerbating global warming and localized heat islands, and therefore alternatives to the energy-intensive technology should be explored and embraced. The structure is more than just a shade canopy though. At its heart is a geothermal system that draws hot air from the perimeter, sends it down a pipe dug deep into the earth, and brings up the cooled air, via a solar chimney, to be introduced via nozzles in the canopy, a bit like those inside a commercial airplane. Faraguna and his team (including geotechnical engineer Alexander Puzrin and structural engineer Mario Monotti) could not bore into the earth beneath the Artiglierie, so they introduce air from a duct in the wall to replicate the effect, and likewise the additional columns visible in my photo above arise from the team not being able to continue the structural mast through the roof of the Artiglierie and therefore stabilize the shade canopy with chains, as Faraguna’s design intends. Even though the installation is therefore not fully formed, its potential impact on site in Bahrain is easy to grasp.

One of the more interesting contributions to the Heatwave catalog is a photo essay of car shades in Bahrain, from the 1950s to the present. Bahrain, like other places around the world that predates the automobile, eventually evolved to cater to the car. With more people driving in Bahrain from the 1950s onward, and with the sun heating up the interior of cars during the day, shade structures were developed to keep the sun off cars while they sat empty, awaiting their owners. Logically, over time the improvised shades grafted onto buildings became more integral to new buildings. The irony of canopies being provided for cars rather than people is not lost on the authors, though the outcome is positive, as the Heatwave proposal takes a similar approach to cooling people who must be outside during the day: construction laborers, market workers, etc.

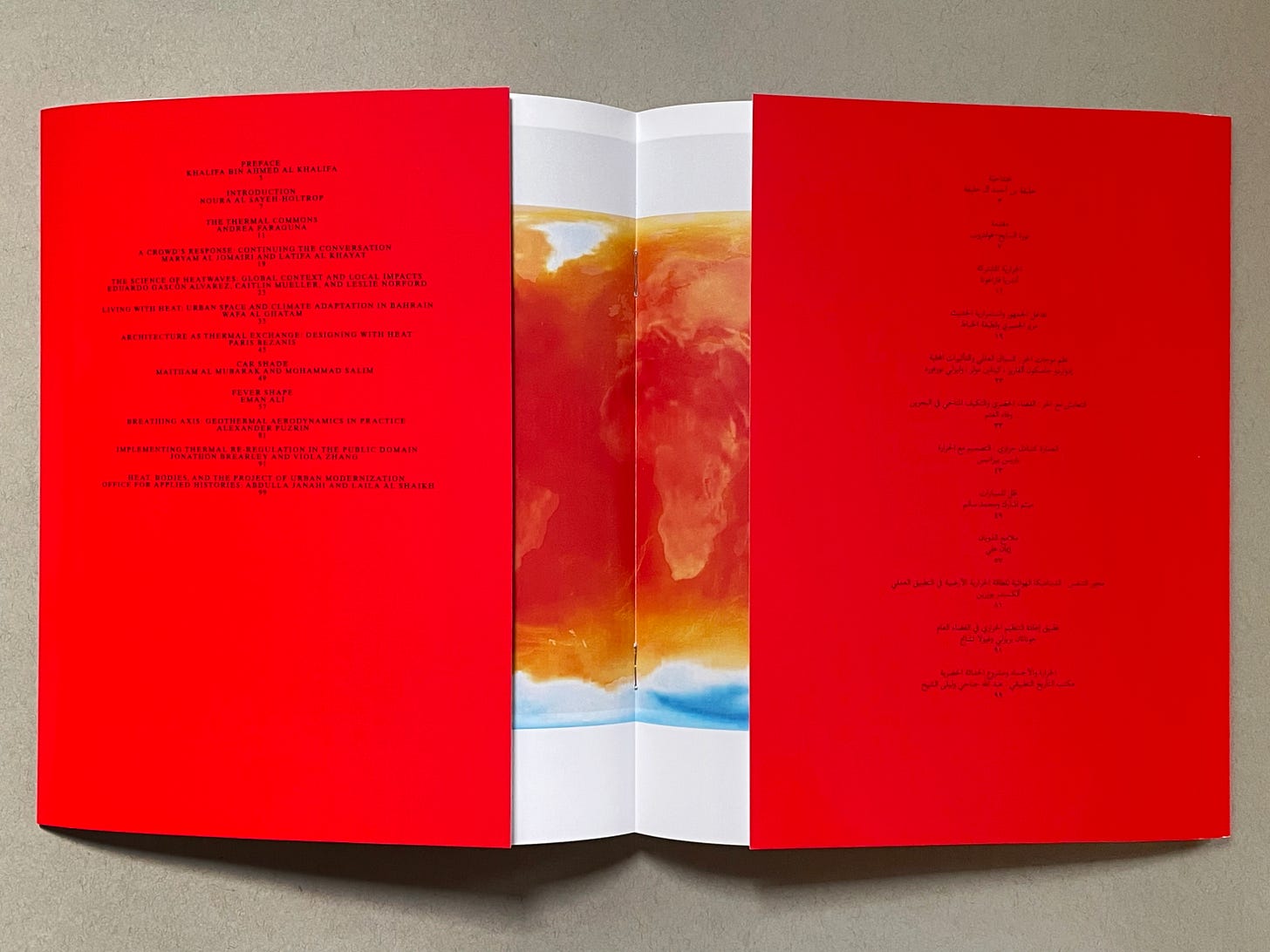

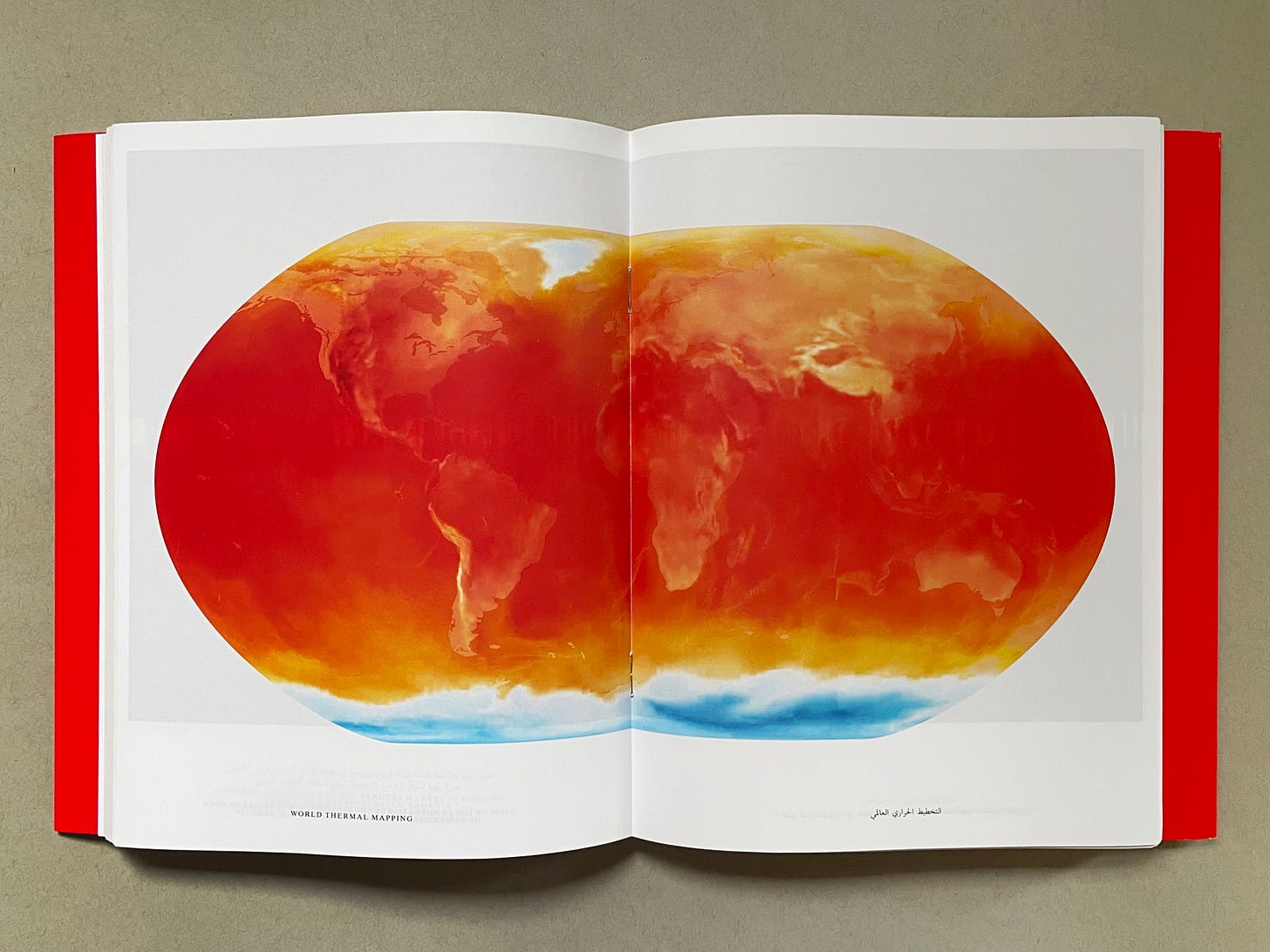

Overall, the contributions to the catalog are balanced between words and images, with photo essays like the car shades taking up nearly as many pages as essays on the design of the prototype, climate adaptation in Bahrain, designing with heat, the science underlying the prototype, and climate adaptation in other parts of the world, among other related topics. Other visual essays show the people and landscape of Bahrain, with a focus on the heat, archival photos of the country’s modernization, and renderings of Faraguna’s shade structure. At the center of the book is a global map that accentuates the planet’s warming: a bold expression of the heatwave that Bahrain is just a small part of.

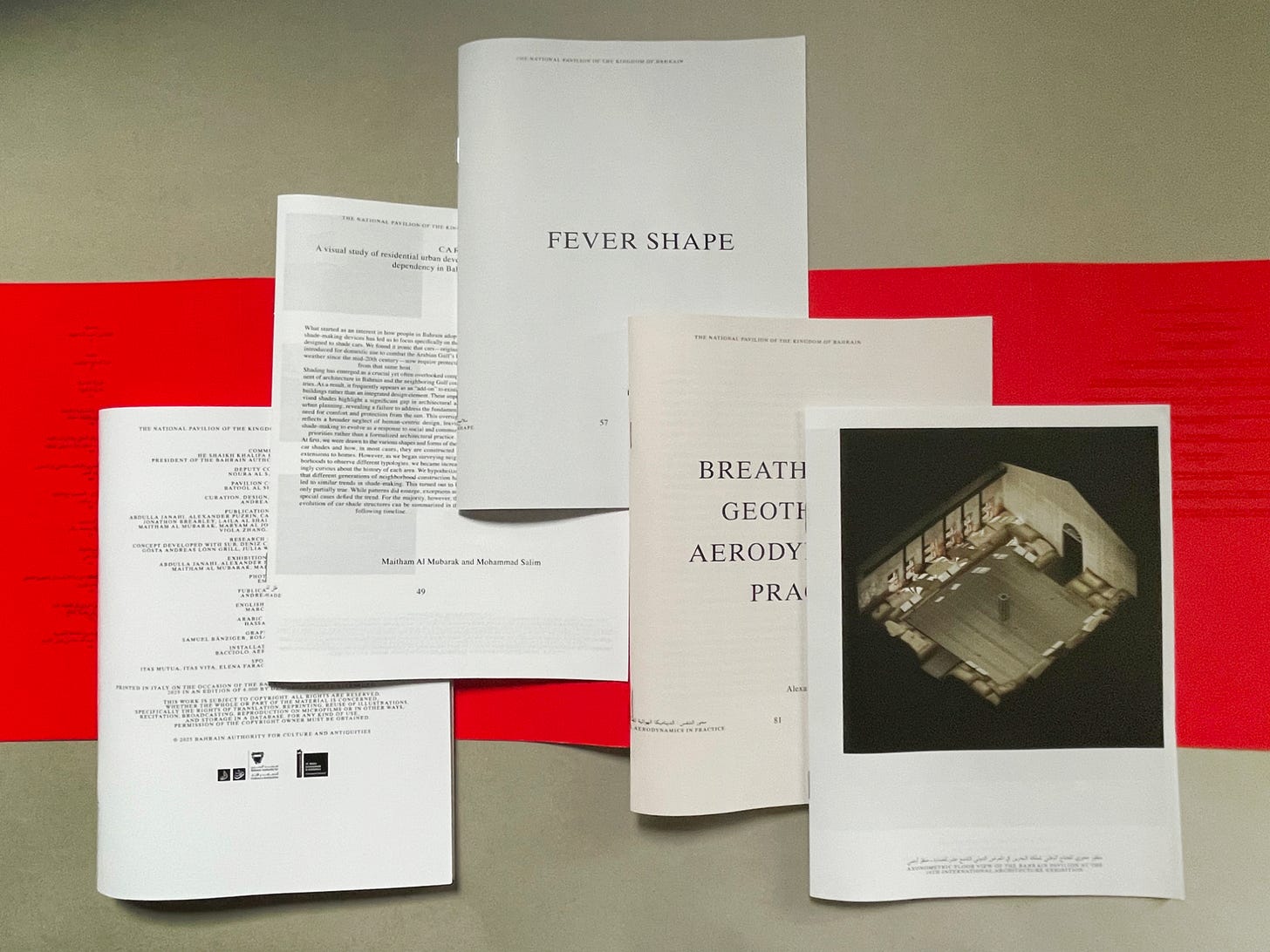

The contents of Heatwave are laudable, but so is the book’s design. Technically, it is actually five books in one—five stapled volumes that nest together, wrapped in the bright red glossy cover. Three of the five booklets are more text than image, so they are printed on lightweight matte paper, while the other two booklets have color images and therefore use glossy paper. Similarly, the booklets with essays are split down the middle, such that the left half is in English and the right half has the same contents in Arabic. Conversely, the visual essays extend from front to back in their respective booklets, with captions in English and Arabic on each page. Given that the contents of the catalog can and should be read differently than other parts of it—some front to back, some just one half—it makes sense to break up the whole into separate volumes. Just as easily as one can remove a booklet to flip through it, one can put it back into place when done, returning Heatwave to its full, nested arrangement—a striking catalog for a remarkable pavilion.

*I’m not aware of any ways to obtain Heatwave other than by picking one up at the Bahrain Pavilion—not until copies show up on ebay, at least.

**By coincidence (I hope), Faraguna is co-founder, with Niklas Bildstein Zaar, of Sub, the Berlin studio that was also responsible for the design of Carlo’s Ratti’s Intelligens exhibition.

Books Released This Week:

(In the United States, a curated list)

Temporary Tecture: Structures of Necessity, by Kosmos Architects (Buy from Birkhäuser / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Temporary Tecture is a fundamental statement on the impact and significance of temporary infrastructures in the city: not only do they ensure the functioning of numerous processes – from construction and dismantling to orientation and protection – but they also shape the cityscape significantly as an overarching structure.”

Full disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, AbeBooks Affiliate, and Bookshop.org Affiliate, I earn commissions from qualifying purchases made via any relevant links above and below.

Book News:

For more Venice Biennale coverage—much more—than mine linked above, check out Will Jennings’ recessed.space newsletter for three articles that looks at the good, the bad, and the ugly.

Design critic Alexandra Lange won the 2025 Pulitzer Prize in Criticism “for graceful and genre-expanding writing about public spaces for families, deftly using interviews, observations and analysis to consider the architectural components that allow children and communities to thrive,” for a series of articles at Bloomberg CityLab. Lange, author of Writing About Architecture: Mastering the Language of Buildings and Cities and, most recently, Meet Me by the Fountain: An Inside History of the Mall, spoke with The Architect’s Newspaper about the prize.

Marilyn Hasbrouck, co-owner of Prairie Avenue Bookshop, died on March 21 at the age of 91; Wilbert Hasbrouck, her husband and co-owner, died in 2018 at age 86. In his remembrance of Marilyn at the Chicago Sun-Times, Lee Bey spoke with architect Charles Hasbrouck, one of their sons, who clarified: “A lot of people thought that was my dad’s bookstore. In fact, while they were partners on all [of their endeavors, the bookstore] was always my mother’s. She was the proprietor. She ran the bookstore.”

William Stout Architectural Books has a new “refreshed identity,” The Architect’s Newspaper reports, and a redesigned website that does iron out some of the kinks of the predecessor (I described a few on my blog two years ago). The redesign doesn’t seem to reflect the breadth of the store just yet—they must have many times more than just 579 architecture books in stock!

Over at his newsletter Interminable Flights, Kazys Varnelis looks deeply “On the Golden Age of Blogging.” It’s a long piece, with some autobiographical and technical content in there, but it’s worth the read—and I’m not just saying that because there are two or three mentions of yours truly in there.

From the Archives:

As mentioned in this week’s Book of the Week, past Venice Architecture Biennales found me, like a kid in a candy store, absconding with as many exhibition catalogs as I could manage home. Here are covers of some of those:

And here are my blog old blog posts where I wrote about them:

My Biennale Haul (2023)

Biennale Publications (2018)

More Biennale Publications (2018)

Fundamentals (2014)

Thank you for subscribing to A Weekly Dose of Architecture Books. If you have any comments or questions, or if you have your own book that you want to see in this newsletter, please respond to this email, or comment below if you’re reading this online. All content is freely available, but paid subscriptions that enable this newsletter to continue are welcome — thank you!

— John Hill

Thankyou for the shoutout, John!