This newsletter for the week of June 2 looks at a couple recently published books that focus on the relationship between architecture and climate change, both of which are companions to exhibitions: one a curated biennale, the other a university show. There’s also the usual new releases, headlines (lots of ‘em!), and a book from the archive related to these two Books of the Week. Happy reading!

Books of the Week:

It's About Time: The Architecture of Climate Change, edited by Derk Loorbach, Véronique Patteeuw, Lea-Catherine Szacka and Peter Veenstra (Buy from Artbook/DAP [US distributor for nai010 Publishers] / from Amazon / from Bookshop)

Transcalar Prospects in Climate Crisis: Architectural Research in Re/action, edited by Jeffrey Huang, Dieter Dietz, Laura Trazic and Korinna Zinova Weber (Buy from Lars Müller Publishers / from Amazon / from Bookshop)

When I think about the changes in publishing over the last few decades and consider the types of architecture books that continue to be made, two categories that are just behind monographs in terms of frequency are exhibition catalogs and university publications. This makes some sense, given that a catalog can broaden an exhibition’s audience and extend its reach far beyond its potentially limited audience and relatively short duration, and books produced by universities can serve as outreach, a way of marketing an architecture school to the world beyond its gates. Due to their nature, both venues also tend to tackle timely and relevant issues, something other architecture books do but not necessarily as speedily; buildings take years to realize, so the ideas embedded within them are often dated by the time they are documented, and theories tracing similar ideas can take years to flesh out. Exhibitions, educational seminars, and the like are relatively compact, usually one or two years from gestation to publication. More than considerations of speed, if exhibitions and schools don’t confront important issues they suffer from potential irrelevancy. If they are out of step with pressing matters, who will pay attention to them?

Not surprisingly, climate change is the main issue in the third decade of the 21st century—at least in a European context, as witnessed by these two recently published books, both of which came out of exhibitions that took place a few years ago: It’s About Time, the 10th edition of the International Architecture Biennale Rotterdam (IABR), took place in fall 2022; Transcalar Prospects in Climate Crisis was exhibited in Lausanne, Switzerland, at the end of EPFL Architecture’s 2022-23 school year. While the first was a major curated exhibition and the second was a roundup of educational research activities, both addressed the role of buildings in rising global temperatures caused by the release of carbon emissions: 40% coming from buildings, an oft-repeated statistic. The impetus for It’s About Time was the 50th anniversary of the publication of The Limits of Growth, the Club of Rome’s 1972 report on the carrying capacity of the Earth being burdened by population growth. Transcalar Prospects looked at the acceleration of climate change as documented at COP27 in 2022, following a brief lull in carbon emissions during the pandemic. Curiously, if Carlo Ratti’s Intelligens exhibition at this year’s Venice Architecture Biennale is any indication, in a short amount of time architects have moved from reducing carbon emissions via adaptive reuse, material selection, renewable energy, and other approaches to adaptation: designing for the rising temperatures and rising sea levels that architecture has contributed to and wider society has been unable to abate. Are exhibition and education therefore now too slow to keep up with social and environmental changes?

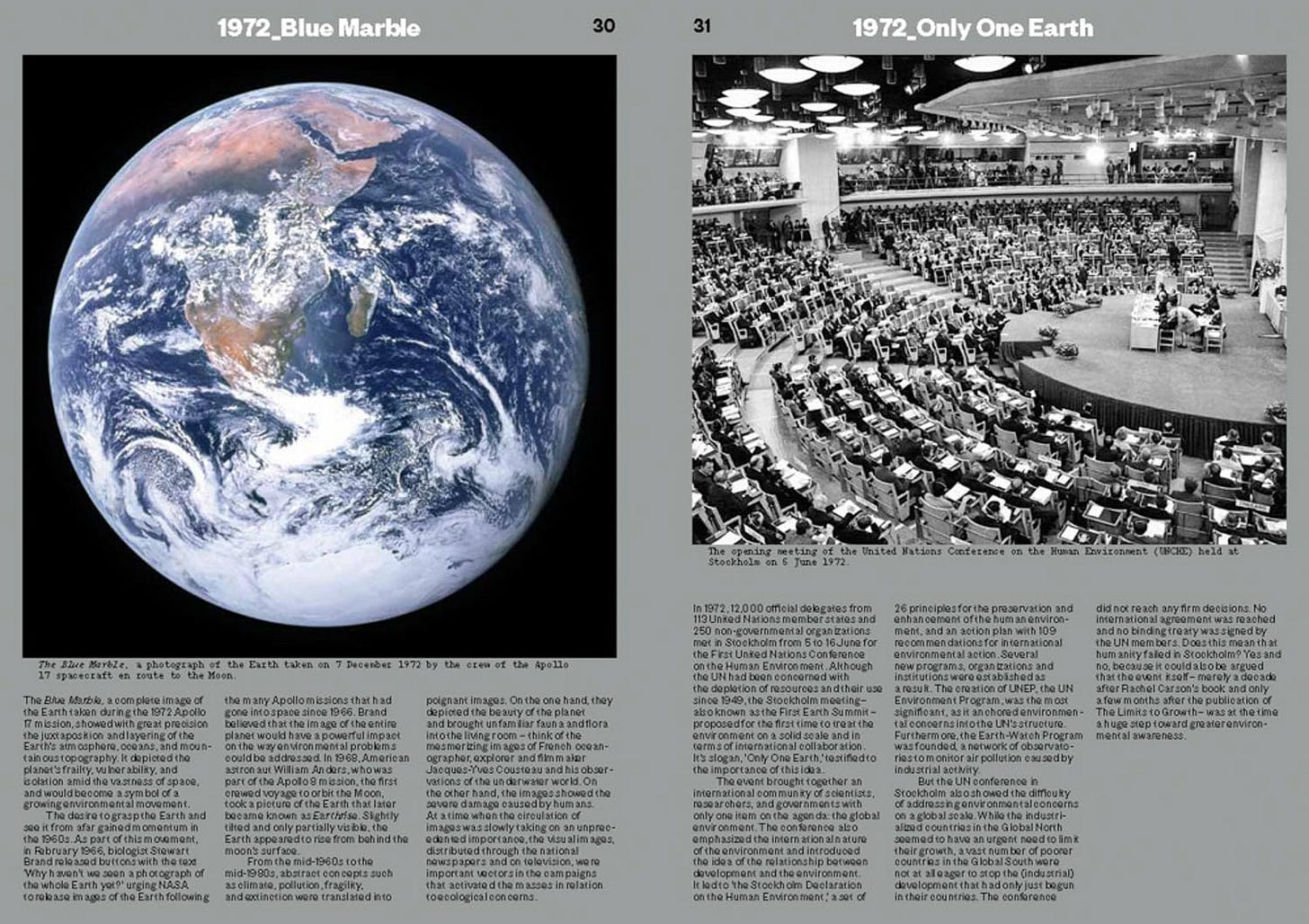

Time is explicitly part of It’s About Time: The Architecture of Climate Change, a double entendre that can be taken literally or familiarly, as in “it’s about time people started addressing climate change.” That scientists and others have been alerting humanity to the toll resource extraction, pollution, and overpopulation were having and would have on the natural world is expressed in the 70-year timeline that comprises about a third of the book. The timeline is made up of notable events, documents, meetings, and other relevant milestones, such as NASA releasing a photograph of the Earth from space in 1972 (above spread), which in turn “activated the masses in relation to ecological concerns,” the 1987 Montreal Protocol addressing the ozone layer, and the 2015 Paris Agreement. These three examples fall into the three chronological timelines that structure the book, each spanning between 20 and 30 years and each timeline addressed in essays by the curators/editors. As such, the book is as much a history of ideas and artifacts as it is a call for “radical thinking and pragmatic action” on the part of architects.

Of the three parts, I mostly liked the second, “Sustainable Architectural Experiments,” which spans from 1972 until 1993 and features a trio of essays by Véronique Patteeuw and Lea-Catherine Szacka. Together they look at how books, buildings, exhibitions, and other creations in those years reflected different approaches to living sustainably: through technology, by building lightly on the land, and by taking long-term views. Eleanor Raymond’s Dover Sun House, Steward Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog, Ian McHarg’s Design with Nature, and Bernard Rudofsky’s Architecture Without Architects may be things of the past, but they can still offer lessons to contemporary architects wanting to address climate change.

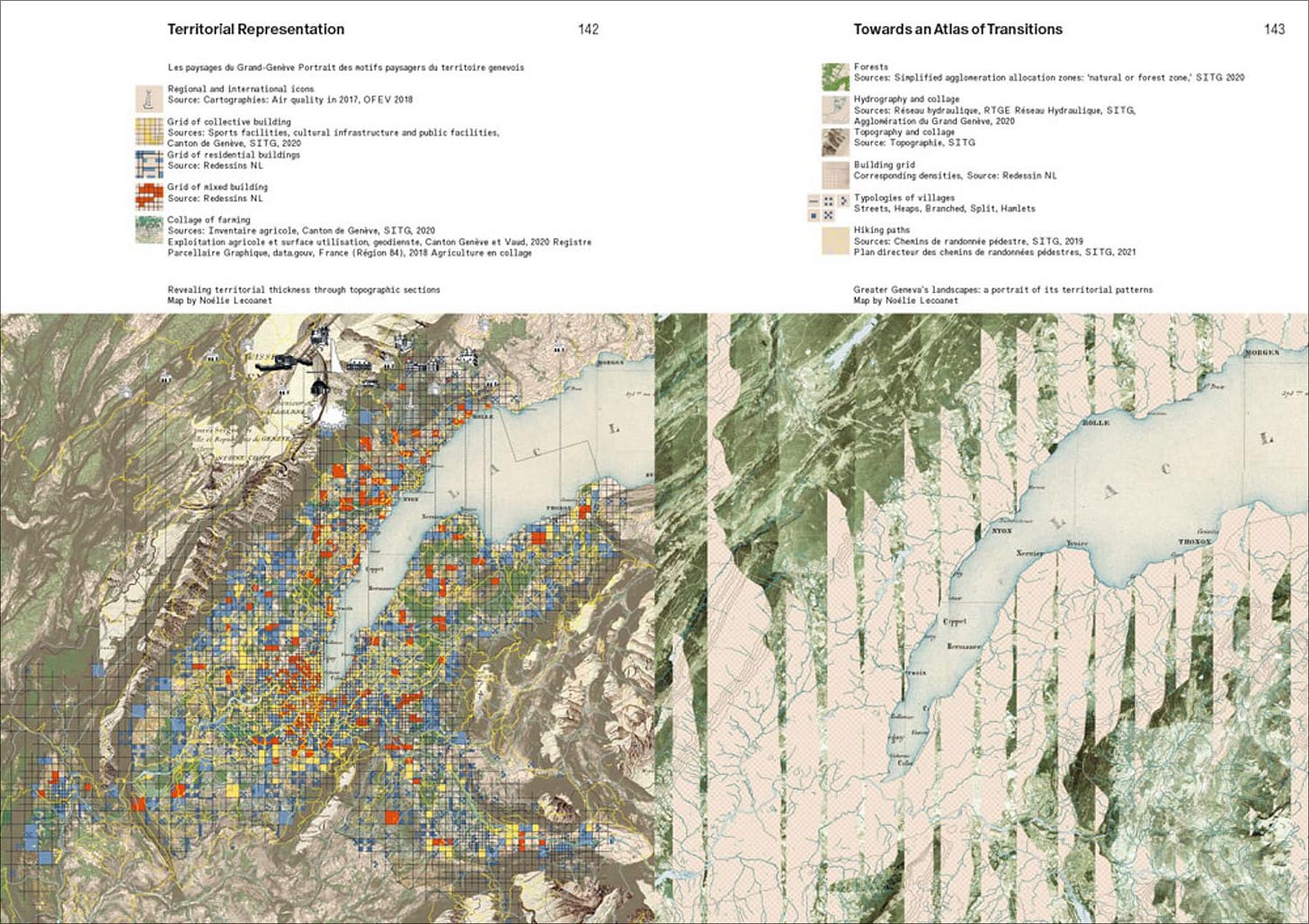

Patteeuw also make an appearance in one of the seven chapters that comprise Transcalar Prospects in Climate Crisis: Architectural Research in Re/Action. “Failed Futures: Circular Construction in Countercultural America,” basically a refashioning of Patteeuw and Szacka’s research from IABR, falls in the last chapter, “Material Re/Use,” following chapters on “Effects,” “Space,” “Territorial Representation,” “Flows,” “Typologies,” and “Building Techniques.” The seven chapters—or “meta-positions,” in the book’s lingo—serve to “reshuffle” the 35 contributions from the 2023 exhibition and express the themes then addressed by researchers at EPFL Architecture. Prefacing the handful of projects in each chapter is a theoretical essay, with Charlotte Maltherre-Barthes, Pier Vittorio Aureli, Jo Taillieu, and others joining Patteeuw as contributors.

If It’s About Time is about mining history, the projects in Transcalar Prospects are strongly rooted in the present. Think of a contemporary approach to dealing with the climate crisis and it’s probably in here, accompanied by quite a few surprises. There are eco-materials, robotics, digital mapping, preservation, the circular economy, and many other areas being studied by researchers at EPFL Architecture. Each exhibited case study is documented in just a handful of pages in the book, though some of them are contenders for their own publications—and the notes indicate at least one of them already is. The book, nicely produced by Lars Müller Publishers, is a strong expression of the school’s strengths, though it’s also a handy resource for architects and architecture students elsewhere who are looking to make positive change.

Books Released This Week:

(In the United States; a curated list)

Suspended Moment: The Architecture of Frida Escobedo, edited by Max Hollein (Buy from The Met / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “An illuminating profile of one of today’s most innovative and forward-looking architects, whose materials-based practice explores how space can provoke emotional response.” (Published by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Escobedo’s client for the Tang Wing for Modern and Contemporary Art.)

The Archival Exhibition: A Decade of Research at the Arthur Ross Architecture Gallery, 2006–2016, by Mark Wasiuta (Buy from Columbia University Press / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “As the title suggests, The Archival Exhibition: A Decade of Research at the Arthur Ross Architecture Gallery, 2006–2016 both records the possibilities of the archival exhibition as a mode, method, and problem of architecture, and is itself a record of a decade-long curatorial project that sought to reframe the documents, authors, environments produced by and producing architecture.”

Full disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, AbeBooks Affiliate, and Bookshop.org Affiliate, I earn commissions from qualifying purchases made via any relevant links above and below.

Book News:

Them's Fightin' Words! At Architect’s Newspaper, Diana Budds covers how architectural criticism has shifted from books to phones and computer screens: “It’s more fun, and digestible, to scroll through a series of before-and-after photographs showing [Robert Moses’s] impact on cities than pick up a book.” Sorry, Robert Caro.

Email updates from Columbia University Libraries hit my inbox infrequently, so I'm just now seeing this story from April: “Wright-ing the Women In: Updating and Linking Archival Data in Avery Library’s Frank Lloyd Wright Collections,” about one aspect of the Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library's ongoing processing of the expansive Frank Lloyd Wright Digital Archive.

The New York Times has an obituary (gift link) on Robert Campbell, the longtime architectural critic at the Boston Globe, who died in April at the age of 88. Campbell won the Pulitzer Prize for distinguished criticism in 1996, one of the few architecture critics to do so.

In a guest post at The Chicago Blog of the University of Chicago Press, Charlie Hailey talks about installing his book The Porch: Meditations on the Edge of Nature inside the US Pavilion as part of the Venice Architecture Biennale.

Read the inaugural issue of Lake Flato's Notes from the Field, a “collection of essays, interviews, fiction, poetry, and art [that] is intended to celebrate [the Texas firm’s] core commitment to creating environments that enrich communities and nurture life.”

A&B has a review of Concrete. The Dark Side of Building, a comic by Alia Bengana, Claude Baechtold, and Antoine Maréchal, the last of whom is described as “a French architect dedicated to telling the story of the built environment through illustration.”

Read a review of Nora Wendl's Almost Nothing: Reclaiming Edith Farnsworth at Third Coast Review.

Over at BD, Jan Kattein explores Brian Holland’s “compelling new book,” Architecture and Social Change: Shaping an Impactful Practice, “which brings together 15 practitioners reimagining architecture as a tool for justice, collaboration and civic empowerment.”

From the Archives:

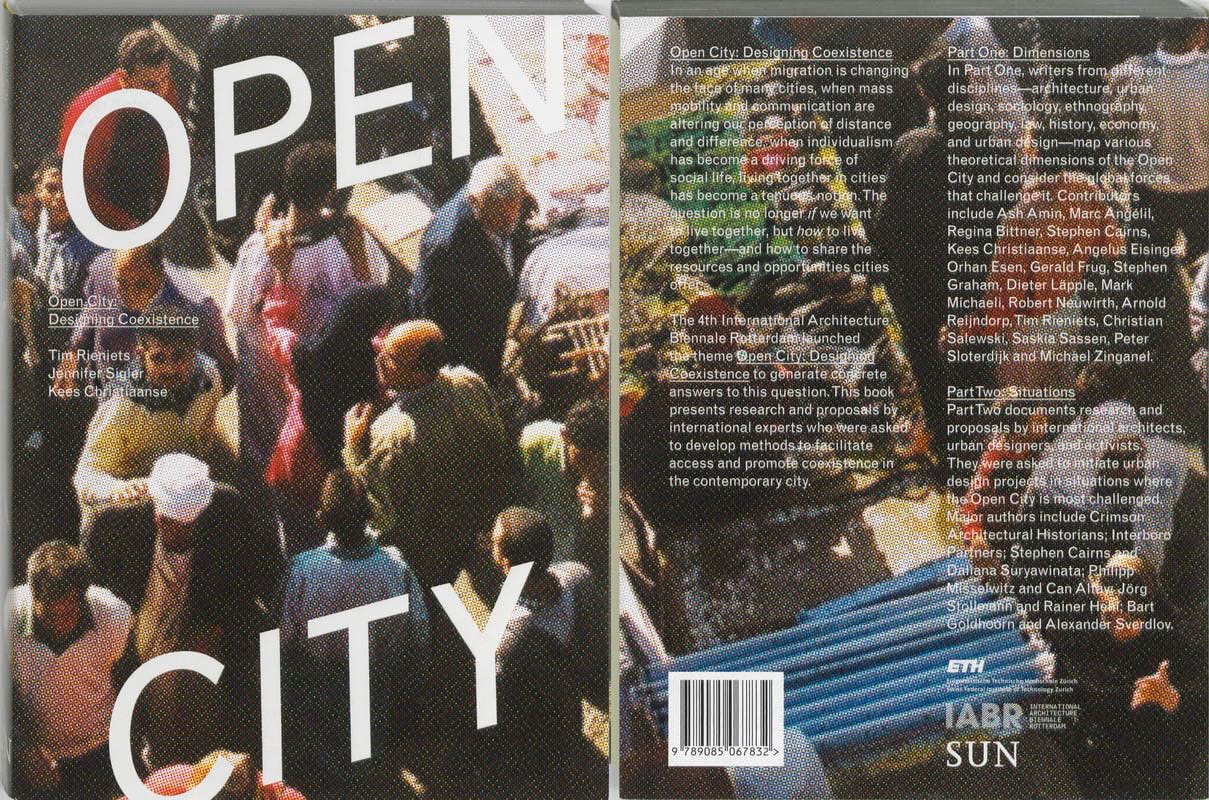

Digging through the my old blog to find a book related to the two Books of the Week, I rediscovered Open City: Designing Coexistence. The book, edited by Tim Rieniets, Jennifer Sigler and Kees Christiaanse, accompanied the 4th International Architecture Biennial Rotterdam in 2008. Here is what I wrote back in 2010:

One of the exhibitions in the 4th International Architecture Biennale Rotterdam (IABR) was Open City: Designing Coexistence, curated by Kees Christiaanse with Tim Rieniets. The exhibition and accompanying book ask not “if we want to live together, but how to live together—how to share the resources and opportunities cities offer.” From the perspective of someone living in New York City, the question certainly is not easy (it probably isn't for anyone in any context), but at times it can seem impossible. Opportunities for lower- and even middle-income individuals and families are more sparse and difficult than ever, particularly in Manhattan, as the city draws the small percentage of the upper-upper-income bracket with developments that price out the many. These and other practices point to the inverse of coexistence, a segregation of movement and opportunity linked to gentrification. But at other times I have a much different take on the openness of New York City, as much of its pleasures are available basically for anyone for free, given the relatively unencumbered physical interaction the city affords. Sure, we can't all dine at the Four Seasons, but the Seagram's Building's plaza allows people of any ilk to enjoy the space, even as public space in Manhattan becomes more restricted. My point is that what we consider the Open City is a matter of perspective as much as it is a measurable quality.

Tackling the complex issues of the exhibition's theme requires defining what the Open City is, how it came about, and what affects it. These theoretical explorations comprise the first half of the book, influencing how, for example, my own definition of the Open City presented above can be expanded or nuanced to incorporate other considerations. In the second half “architects and urban designers were asked to explore ways in which spatial design practices could be applied to create the conditions needed for an Open City.” These explorations made up the physical exhibition at the IABR, such as Interboro's two-part look at American communities; the Arsenal of Exclusion & Inclusion is especially interesting and analogous to the overall exhibition in terms of its complexity and the importance of defining and articulating what the Open City is. Interboro obviously focuses on the US, but a plethora of other countries and regions are represented in part two. This makes the exhibition truly international and more a survey of how practices and thinkers tackle the idea of the Open City, rather than a kit of parts for different cities to implement.

Thank you for subscribing to A Weekly Dose of Architecture Books. If you have any comments or questions, or if you have your own book that you want to see in this newsletter, please respond to this email, or comment below if you’re reading this online. All content is freely available, but paid subscriptions that enable this newsletter to continue are welcome — thank you!

— John Hill