This newsletter for the week of July 14 looks at Begin Again. Fail Better, a catalog of drawings made as a companion to an exhibition of the same name at Kunstmuseum Olten a year ago. On a similar note, First Works: Emerging Architectural Experimentation of the 1960s & 1970s is the book from the archive, while the usual headlines and new releases are in between. Happy reading!

Book of the Week:

Begin Again. Fail Better: Preliminary Drawings in Architecture and Art, edited by Helen Thomas, Dorothee Messmer, Katja Herlach and Manuel Montenegro (Buy from University of Chicago Press [US distributor for Park Books] / from Amazon / from Bookshop)

Spending time with an old college classmate who was in New York City on vacation recently, our conversation moved to AI and its impact on architectural education and practice. I had just read Neil Leach’s Architecture in the Age of Artificial Intelligence, and while I appreciated learning more about the ways architects could harness AI for design and production, the pro-AI book didn’t convince me that architects should not still be capable of drawing and building models—two activities that foster a sense of spatial reasoning and architectonics. So I was glad to hear that my friend still has her students drawing and building models, both by hand. I was even more pleased that, instead of being discouraged or frustrated, her students liked it. Perhaps these increasingly anachronistic processes are being embraced by Gen Z in the same way they are drawn to cassette tapes and other old technologies, though I’d like to think that certain irreproducible qualities of drawings and models also make them more appealing than AI-generated renderings.

One such quality is mistakes. AI-generated architectural renderings are full of mistakes, many of them comical and most of them a sure sign of AI’s lack of actual intelligence. Architects, by virtue of being human, also make mistakes in drawings and models—smudging a sketch, for instance, or fraying chipboard with a dull X-Acto blade. While AI mistakes may elicit a shake of the head, some handmade mistakes may spark inspiration by revealing something not seen before. I remember being frustrated at the start of a project in architecture school decades ago and furiously scrawling away with a marker on trace paper, not caring what I was drawing. The resulting scribbles were surprisingly appealing and became the formal basis for the project, much like the early gestural, eyes-half-closed sketches by Coop Himmelb(l)au. I’m guessing every architect has had a similar experience, in which early mistakes—or failures—are nevertheless valuable parts of an architectural design’s early stages.

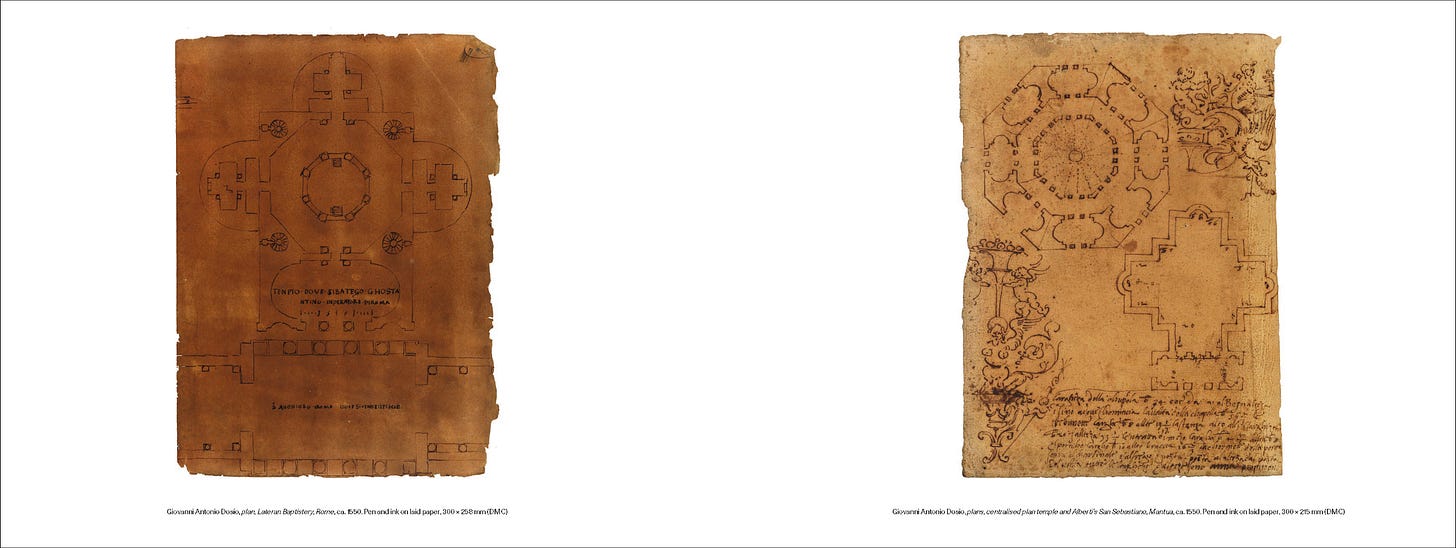

As its title clearly indicates, Begin Again. Fail Better: Preliminary Drawings in Architecture and Art gathers such early sketches—around two hundred of them, evenly split between drawings by contemporary Swiss architects and those by architects from the 20th century and earlier centuries, the latter gathered from a handful of archives, including Drawing Matter in London and both EPFL and ETH Zurich in Switzerland. Published in the US earlier this year by Park Books, the book is a companion to an exhibition of the same name staged at Kunstmuseum Olten (in Olten, Switzerland) from summer 2024, based on the idea and research of Manuel Montenegro, and curated by Montenegro with Helen Thomas, Marco Bakker and Dorothee Messmer.

The book presents two drawings per architect/firm on one spread each: the drawing on the left being an early sketch and the drawing on the right being a later, more developed drawing or in some cases a photo of model or some other type of output/image. The pairs of images are presented in chronological order by the architect’s name, meaning the book jumps around in time: from Conen Sigl’s 2017 sketches of Hochbord Dübendorf followed Giovanni Antonio Dosio’s 16th-century floor plans of two churches, for example, to Dreier Frenzei’s 2012 sketches of Ecoquartier Jonction followed by William Dunkel’s drawings of the Stampfenbach development in Zurich from 1927. Breaking up the couple-hundred drawing are eight “interludes”—short texts by architects, curators, critics, and others invested in drawings and/or Swiss architecture—and the book ends with essays by Messmer, Thomas, and Bakker, and a handful of old texts by Alvaro Siza selected by Montenegro.

With its simple hook based on a snippet from Samuel Beckett’s Worstward Ho, Begin Again. Fail Better shouldn’t have a hard time finding its audience. (Given that the book is on backorder with the US distributor, I’m guessing that has already been the case.) Aiding the book’s appeal is its design—by Studio Mathias Clottuand, who also did the lovely Alternative Histories for Drawing Matter—and its production. With its stapled linen softcovers and thick papers, the A4-size book in landscape orientation resembles an oversized architect’s sketchbook, which makes flipping through the book feel like such. The drawings are big on the pages, making details easy to grasp and the qualities of each drawing easy to appreciate. Although the interludes are listed by page number in the table of contents, the book is not paginated; this is frustrating if you’re trying to find a particularly interlude, but the lack of page numbers makes sense for a book that is about slowly and carefully poring over drawings. One doesn’t need to look for the mistakes or failures in the drawings to appreciate what the curators/editors have assembled.

Books Released This Week:

(In the United States; a curated list)

Design for Construction: Tectonic Imagination in Contemporary Architecture, by Eric Höweler (Buy from Routledge / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Arguing that a gulf exists between design and construction, between conceptual thinking and the constructed building, this book explores projects and practices that span the gap by thinking through materials and processes with what Höweler calls a tectonic imagination.”

Materiae Palimpsest, by Khalil El Ghilal and El Mehdi Belyasmine (Buy from Artbook/DAP [US distributor for Kaph Books] / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Far more than a simple presentation of the Moroccan Pavilion at the 19th Venice Biennale of Architecture, Materiae Palimpsest provides insights into its construction using exclusively local materials.”

Biography of a Tenement House in New York City, by Andrew S. Dolkart (Buy from University of Virginia Press / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — The third edition of this “Architectural History of 97 Orchard Street” on Manhattan’s Lower East Side “includes new research on the basement storefronts (specifically the Schneider saloon and the kosher butcher), the backyard privies and their reconstruction, and the new Irish Moore apartment.”

The Belgian Friendship Building: From the New York World's Fair to a Virginia HBCU, by Kathleen James-Chakraborty, Katherine M. Kuenzli, and Bryan Clark Green (Buy from University of Virginia Press / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “How did the Belgian Friendship Building, originally constructed for the 1939 New York World’s Fair—and one of only a few surviving buildings from that celebrated exhibition—end up on the campus of an HBCU in Richmond, Virginia?” This book reveals the story.

Full disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, AbeBooks Affiliate, and Bookshop.org Affiliate, I earn commissions from qualifying purchases made via any relevant links above and below.

Book News:

Over at The Architect’s Newspaper, Kate Wagner reviews Incorporating Architects: How American Architecture Became a Practice of Empire, by Aaron Cayer, who “traces architecture’s role in postwar and Cold War American imperialism through the history of Daniel, Mann, Johnson and Mendenhall (DMJM),” which is now part of AECOM.

Publishers Weekly gives a starred review to Stone: Ancient Craft to Modern Mastery, by Richard Rhodes (Princeton Architectural Press), saying the “gorgeously illustrated” book on the secret rules held by master guildsmen of the Freemasons “beguiles.”

The nonprofit Eames Institute of Infinite Curiosity is acquiring Lars Müller Publishers, which, Architect’s Newspaper reports, “will retain its name, its editorial independence, and its headquarters in Zurich.” This is the Eames Institute’s second foray into architecture books, coming a few years after it acquired William Stout Architectural Books.

Thomas J. Campanella will be speaking about his latest book, Designing the American Century: The Public Landscapes of Clarke and Rapuano, 1915-1965, at the Skyscraper Museum on July 22. It's a free in-person program (RSVP via link at left) that will also be live streamed on the museum's YouTube channel.

STIR World takes a peek inside photographers Stefano Perego and Roberto Conte's Brutalist Italy: Concrete Architecture from the Alps to the Mediterranean Sea (Fuel).

From the Archives:

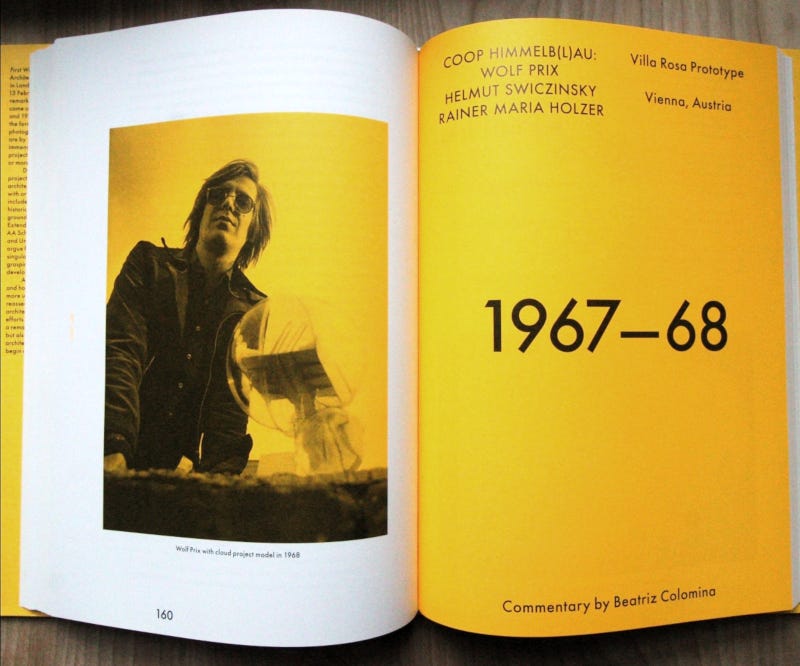

The drawings made at the beginning of a project, as covered in the Book of the Week, got me thinking of architects’ early works, something explored in First Works: Emerging Architectural Experimentation of the 1960s & 1970s, edited by Brett Steele and Francisco González de Canales, published by AA Publications in 2009. The book “features key early projects of 20 young architectural practices of the 60s and 70s, together with commentaries by invited critics, including Kenneth Frampton, Sylvia Lavin and Pier Vittorio Aureli.” I reviewed it on my blog in 2019, writing this:

First Works was an exhibition held at the Architectural Association in London in late 2009 and early 2010. It must have been difficult to develop an exhibition that did not seem superfluous in the midst of the Great Recession. In turn, First Works looked back about a few decades to present exactly that: the first projects of now-famous architects who started their careers in the 1960s and 70s. Those decades saw social upheaval in response to many crises, including the Vietnam War and environmental concerns, and the overlapping concerns of the housing crisis and climate change made it imperative at the tail end of the 21st century's first decade to consider one's course of action following architecture school. Or as Brett Steele, then the AA Director, writes in the introduction to the exhibition's companion book, “I would argue that a re-examination of how to begin a critical architectural practice [...] is even more urgent in 2009 then it may have been four decades ago,” a time of “counter-projects and furious experimentation.” Ironically, while the architects explored in First Works (listed on the top half of the book's cover) may have adopted critical practices all those years ago, the ones that survived into this century are firmly established within the status quo, designing buildings for corporations and institutions—buildings that are formally daring but do little to address wider societal or environmental issues.

Steele and curator Francisco González de Canales could have broadened their reach to incorporate architects with a bit more relevancy to the crises graduating architects ca. 2009 would be facing in their practices. Nevertheless, the presentations and commentaries on the first works of Cedric Price, Alvaro Siza, Aldo Rossi, Renzo Piano, Coop Himmelb(l)au and many more are valuable, but more from a historical perspective than in regards to any contemporary context. While many architects are probably familiar with Cedric Price's London Zoo Aviary and Alvaro Siza's Leça Swimming Pools in Portugal, the book is full of relatively obscure projects that over time have been overshadowed by other projects—early, late, built, unbuilt—by the assembled architects. So even though all of the projects are dated, most of them will be fresh to readers. (I always think of The Peak from 1982 as Zaha Hadid's first project, but here it's the Irish Prime Minister's Residence from three years earlier.) The enjoyment of learning about the first works—one per architect, explained in their words, in images, and in the contemporary commentaries by carefully selected critics—is furthered by the candid before-they-were-famous photos of the architects, visible on the cover beneath the dust jacket (photo at top-right) and inside the book at the start of each architect's section. First Works is out of print but is worth picking up if seen in a bookstore, like I did, though not necessarily searching far and wide for.

Thank you for subscribing to A Weekly Dose of Architecture Books. If you have any comments or questions, or if you have your own book that you want to see in this newsletter, please respond to this email, or comment below if you’re reading this online. All content is freely available, but paid subscriptions that enable this newsletter to continue are welcome — thank you!

— John Hill