Driving Design with Data

Architecture Books – Week 32/2025

This newsletter for the week of August 4 looks at Value of Design: Creating Agency Through Data-Driven Insights, a project of the Real Estate Innovation Lab at MIT that examines how quantifiable data can parse how architectural quality leads to financial gains. The book uses Manhattan as a case study for its data-driven insights. This recently published book had me digging out The Creative Destruction of New York City: Engineering the City for the Elite, a 2017 book by Alessandro Busà this is considerably less interested in real estate success. In between are the usual new releases and headlines. Happy reading!

Book of the Week:

Value of Design: Creating Agency Through Data-Driven Insights, by Dr. Andrea Chegut, Minkoo Kang, Helena Rong and Juncheng “Tony” Yang (Buy from ar+d [an imprint of ORO Editions] / from Amazon / from Bookshop)

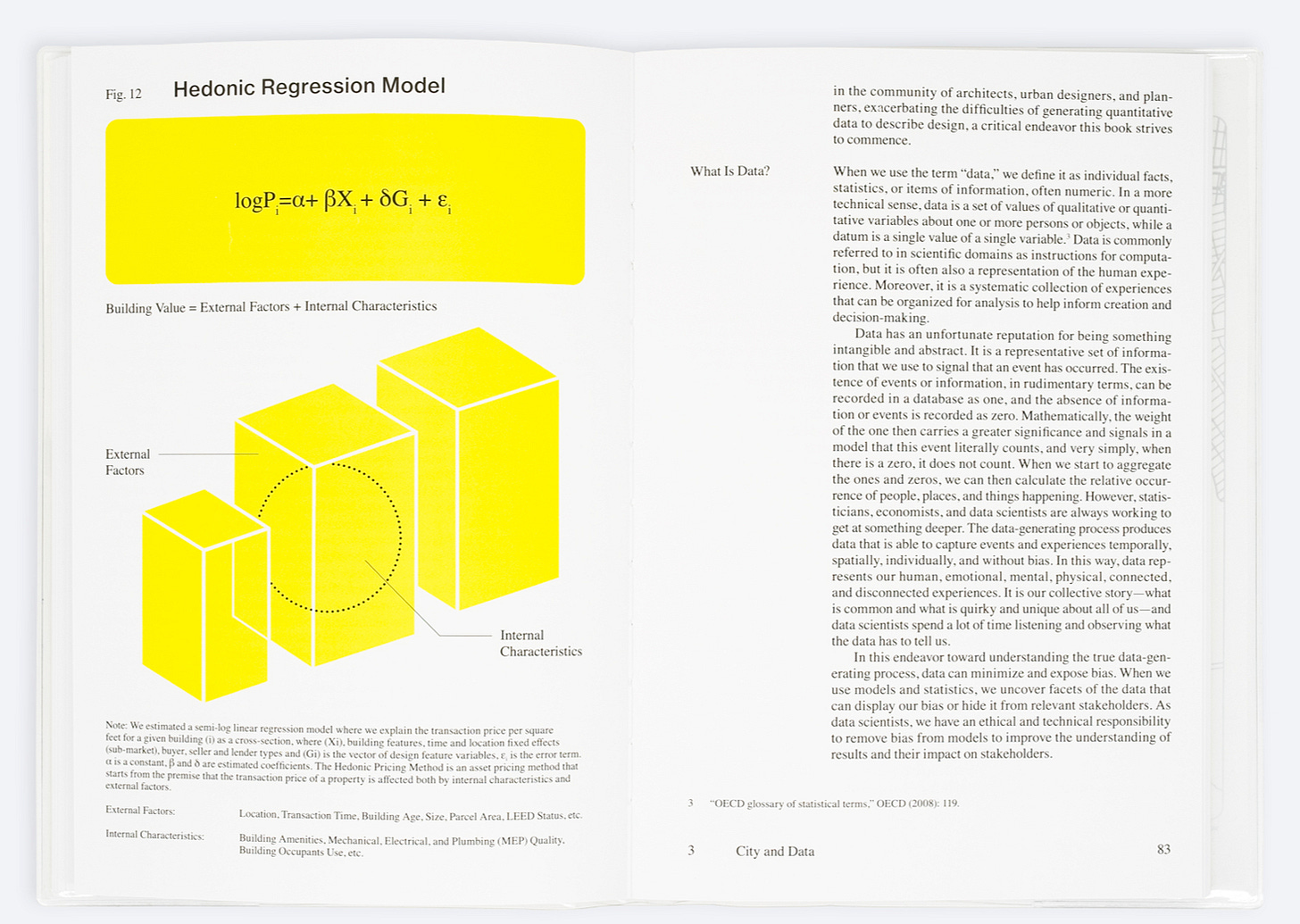

Can data, scientific research, and other quantifiable information be used by architects and their clients to improve the qualities of buildings, both for their users and the environments in which they are situated? Such approaches have occurred now and again, following the ebbs and flows of architectural trends and the willingness of professionals outside of architecture to contribute. The most notable examples were in the 1970s, under the guises of environmental psychology and environmental design, and in the 2000s, at the hands of increased power of computers and the available of sensors in the built environment.

Although the impact of Christopher Alexander and company’s A Pattern Language remains strong (the 1977 book has consistently been atop Amazon’s “Architectural Criticism” bestseller list), any progress made in the seventies was short lived, displaced by a postmodern emphasis on appearance and the rise of neoliberalism worldwide. The more recent incorporation of data into design has tended to be focused at the scale of the city, as with MIT’s Senseable City Lab, or on highly engineered green buildings, or with the experience of users in commercial settings, as with the Gensler Experience Index.

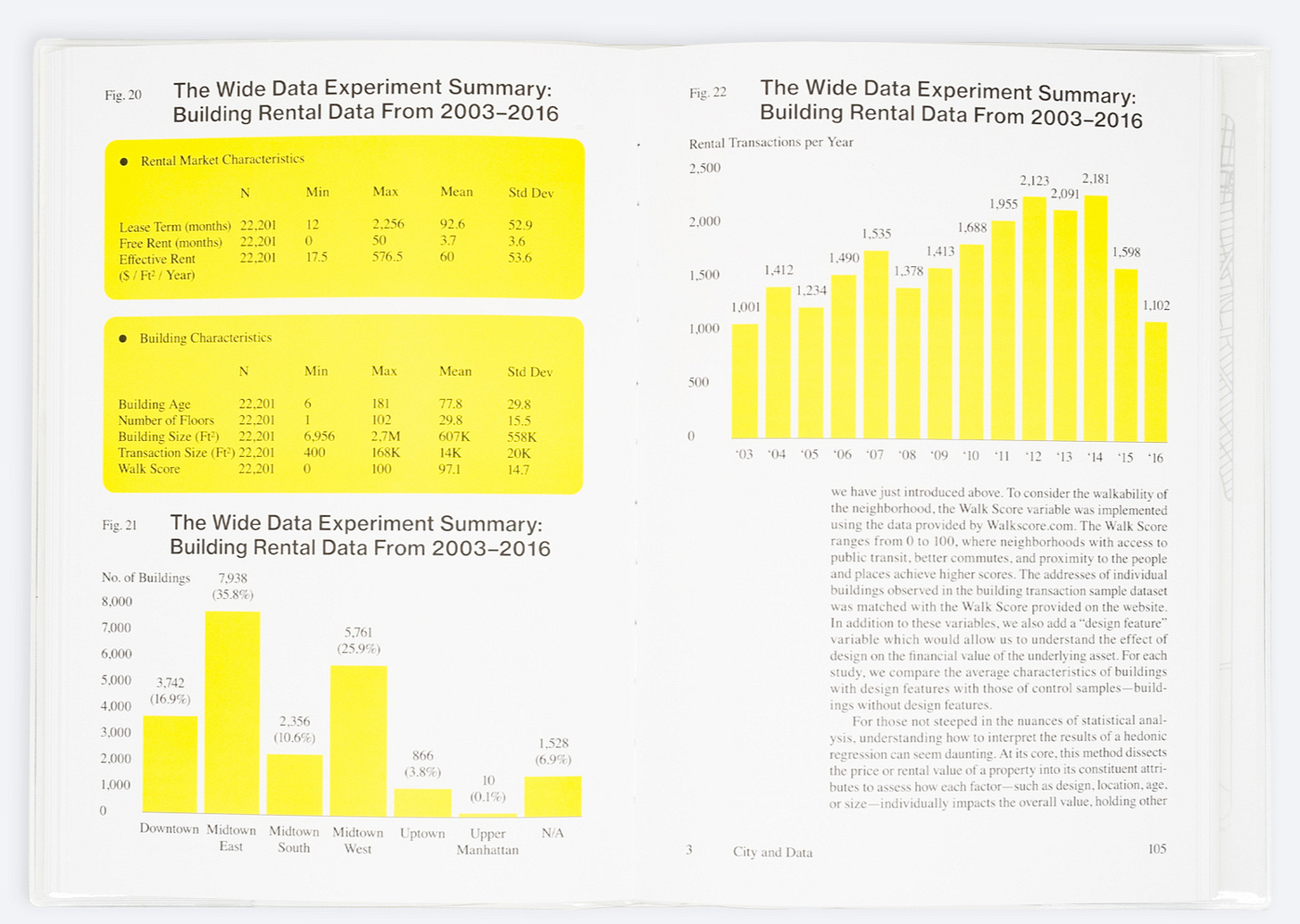

Strongly aligned with Gensler’s relatively recent research are the efforts of the Real Estate Innovation Lab at MIT, whose Value of Design component examined how design impacts real estate prices and attempted, more broadly, to foster “a more comprehensive appreciation of design’s multifaceted contribution to our built environment.” Value of Design: Creating Agency Through Data-Driven Insights, released last month, packages the project’s Manhattan case study, an admittedly “exploratory work” that “bridge[s] the gap between design and finance in architecture and real estate by harnessing the availability of big urban data and sensing technologies.”

Spearheaded by Dr. Andrea Chegut, the Real Estate Innovation Lab’s founder, the future of the Lab’s Value of Design component is tenuous, given Chegut’s untimely death in late 2022. Minkoo Kang, Helena Rong and Juncheng “Tony” Yang, researchers in the Lab, “were determined to advance the work on the project and bring the vision to life.” Although the book is handsome and the general approach of applying data toward the betterment of the built environment is commendable, the book is still tinged by the sadness of Chegut’s passing and the publication being her last statement on the project.

Before reading the book I had questions: Why data? How is quality-based data obtained? Why are the findings applied to real estate, rather than other buildings or spaces? And what about people who don’t live or work in buildings that are the product of profit-driven real estate? First, data is used to counter simplistic metrics that say, for instance, that buildings designed by famous architects command higher rents; the Lab wanted to see how specific elements of design can do the same. Second, the ways data is obtained is explicitly defined across the book’s fourth chapter, as explained below. Third, real estate data is readily available and developers often hire architects, famous or not, for their buildings, making the joining of data and design in real estate appropriate. And fourth, the book’s authors embrace the societal shifts of the last decade or so, meaning the book “not only champions the economic benefits but also emphasizes the social dividends and environmental sustainability that a well-designed built environment can bring.”

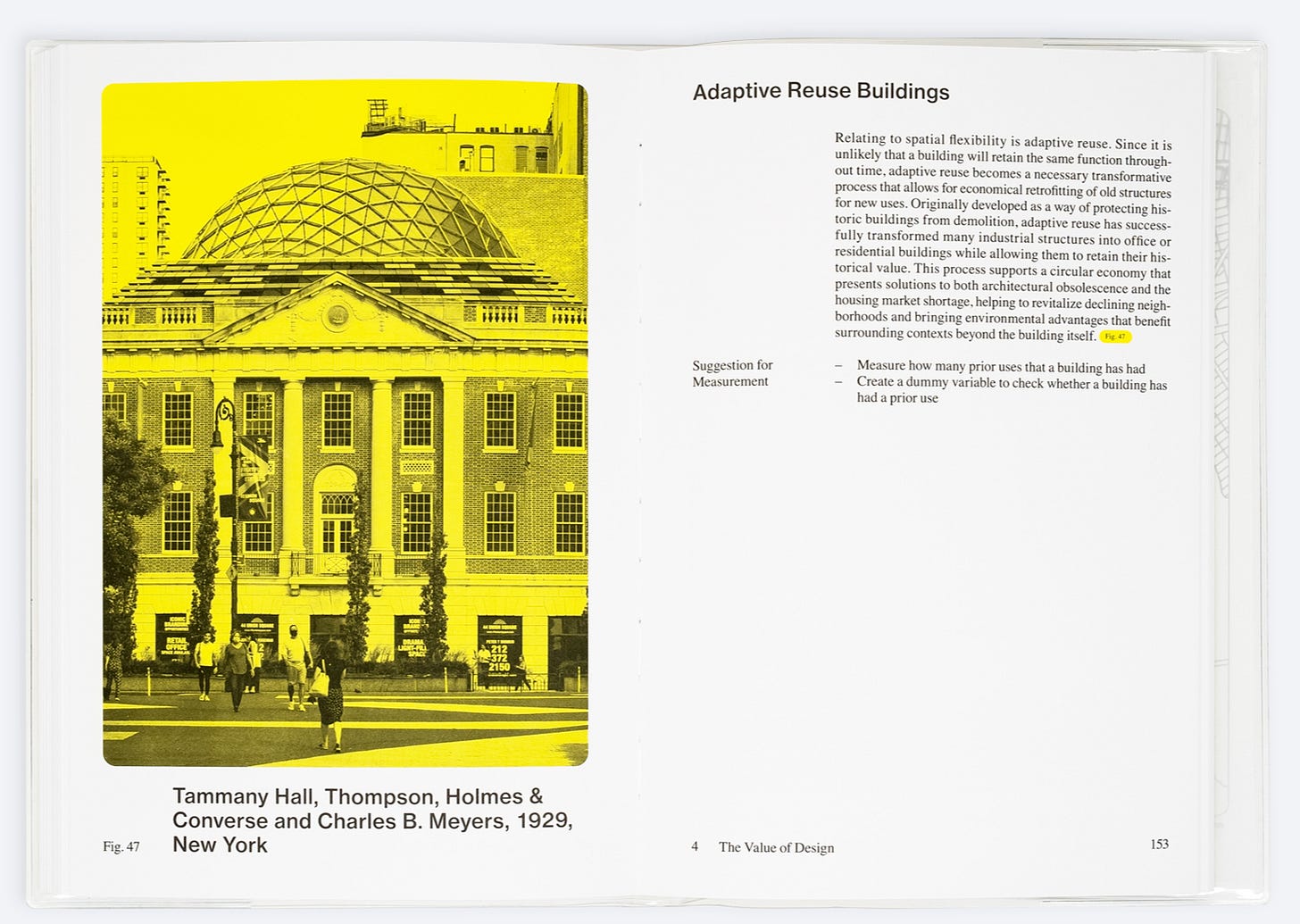

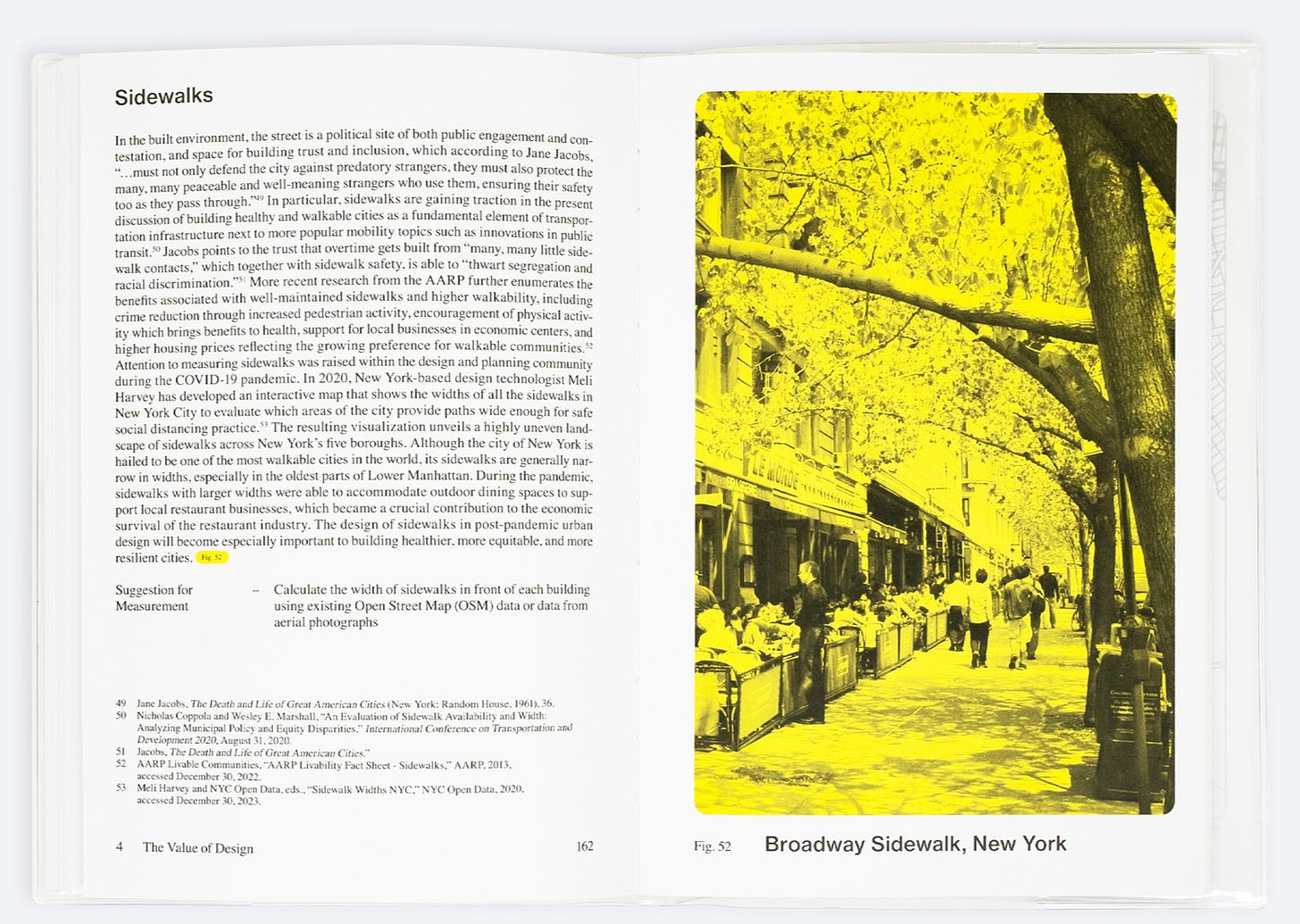

The book—stylish, with its plastic wrappers and pervasive yellow graphics—is organized into four chapters. The first describes the tension between the worlds of architecture and real estate, of an artistic vs. financial approach. The second provides a quick history of Manhattan’s built environment and outlines the book’s case study on the island’s real estate. The short third chapter outlines the data-driven approach that is detailed in the fourth chapter, which comprises almost half of the book’s 224 pages. Here, we see the various design elements—atrium, circulation, balconies, adaptive reuse, street-level greenery, and so forth—and suggestions for how data is obtained for each one. Some are simple, with binary measures, while others require a lot of user input, often combined with algorithms or potentially AI (the last is not explicit in the book, a sign of how much the field has advanced since Chegut’s death three years ago). The incorporation of numerous elements beyond building footprints point to the project’s applicability to urban designers, not just architects and their clients.

The fourth chapter also includes some preliminary findings based on applying data from certain elements at specific Manhattan areas. In one instance, the correlation between urban greenery, articulated via a GVI (green view index), and real estate transaction prices is graphed. Not surprisingly, the prices are higher where there is more visibility of trees and other greenery, and there is a greater impact on residential versus commercial, also not a surprise. Parts like this found me wanting more, as it felt like big data and scads of research were pointing out the obvious. Then I reminded myself that the Lab’s Value of Design project and related book are, in the authors’ words, “exploratory,” i.e., far from complete.

If the project does move forward and certain parts are refined, making it easier for data to be more strongly wed with design “paying off,” then ideally larger swaths of the built environment would become the responsibility of design-minded architects rather than builders, strictly service-oriented architects, and the like. Beyond developers and their architects, I could also see data-driven insights on the “value of design” helping to shape urban environments, with local governments planting more trees, requiring adaptive reuse and sustainable architecture, and making cities more walkable, among other things. Higher rents are good, for both developers and city coffers, but they are hardly the end-all of architectural quality.

Books Released This Week:

(In the United States; a curated list)

Encounters: Denise Scott Brown Photographs, edited by Izzy Kornblatt (Buy from Artbook/DAP [US distributor for Lars Müller Publishers] / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “The first publication dedicated to the perceptive photographic oeuvre of one of the most important postwar architects and co-author of the influential Learning from Las Vegas.” (Read my “Found” on the book at World-Architects.)

Monumental: How a New Generation of Artists Is Shaping the Memorial Landscape, by Cat Dawson (Buy from The MIT Press / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Since 2014, a new generation of artists has established a groundbreaking role for monuments, calling into question the very notion of what a monument is through novel investigations of how symbolic structures can be made and what stories they can tell. This book tells the important story of that sea change.”

Senses of Architecture: Using the Senses to Enhance Architectural Experience, by Ryan Crooks (Buy from BIS Publishers / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Senses of Architecture is a groundbreaking book that challenges the traditional approach to design by emphasizing the often overlooked senses. It explores how engaging all our senses-touch, smell, sound, and even taste-can enhance our experience of spaces, sparking a new wave of inspiration and intrigue among architects and designers.”

Full disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, AbeBooks Affiliate, and Bookshop.org Affiliate, I earn commissions from qualifying purchases made via any relevant links above and below.

Book News:

Salone de Mobile recommends 12 new books, including “a fairy tale from Formafantasma, Rem Koolhaas' villa of mysteries, reissues of cult books by Alice Rawsthorn and Carlo Ratti, and reflections on new ecological literacy.”

Over at PIN-UP, Carlo Antonelli speaks with Sylvia Lavin about her “bookish provocation in Venice”—the “The Perimeter of Architecture: Amid the Elements” installation in James Stirling's Book Pavilion.

Monocle lists “the five architecture and design books you should be reading this summer.”

Edward Dimendberg, who is currently writing a book on architecture documentaries, reviews the streaming service Shelter at Architect’s Newspaper. (Compare with my 2023 review of Shelter on World-Architects, in which I made some similar points that, apparently, are still valid today.)

Issues of Telesis (University of Oklahoma Gibbs College of Architecture), Module (Syracuse University School of Architecture), Thresholds (MIT Department of Architecture), and DATUM (Iowa State University) are recipients of the 2025 Douglas Haskell Award for Student Journals from the Center for Architecture/AIANY.

From the Archives:

The Book of the Week’s focus on the most finance in Manhattan real estate had me thinking of its flip side: a critique of New York City’s shift this century toward elite interests. I read Alessandro Busà’s The Creative Destruction of New York City: Engineering the City for the Elite not long after it came out in 2017, and soon after wrote a review of it on my Unpacking My Library blog. That blog is now defunct, so my review from January 2018 is below.

Although inequality is hardly a 21st-century phenomenon, the gulf between rich and poor, between those with unlimited opportunities and those with very few, is wider than ever this century. And cities are where this plays out. In the US, cities have rebounded this century, with middle- and upper-class individuals and families moving from the suburbs back to the city, and from one city to another. With this trend, cities such as New York have created amenities suited to the upwardly mobile through parks, developments, tax breaks, and other physical “improvements” and financial incentives.

Urban scholar Alessandro Busà takes aim at what New York City has done in the last couple of decades to prioritize people with money over everybody else. Although he doesn't start with Bloomberg, Mayor Mike did the most damage in this respect, rezoning swaths of the city for large-scale residential and commercial developments. The effects are evident (e.g. the High Line, whose transformation into a park was accompanied by a rezoning that has transformed its edges in unbelievable ways) and will unfold for years (e.g. Hudson Yards and Atlantic Yards) given the scale of the projects he focused his administration on.

Busà discusses these three areas, among many others, but two chapters delve deeper into two less-considered places: 125th Street in Harlem and Coney Island in Brooklyn. Both were prey to rezonings that benefited developers and new tenants more than already established residents. Busà also delves into the way New York has branded itself since the famous I♥️NY campaign from the 1970s. More than the chapters on rezoning, capital, and the production and consumption of city life, these are the chapters where I learned the most—chapters where theory and criticism are applied to focused and nuanced instances of the city being “engineered for the elite.”

Thank you for subscribing to A Weekly Dose of Architecture Books. If you have any comments or questions, or if you have your own book that you want to see in this newsletter, please respond to this email, or comment below if you’re reading this online. All content is freely available, but paid subscriptions that enable this newsletter to continue are welcome — thank you!

— John Hill