This newsletter for the week of June 23 looks at a few books by Richard Rogers, including the just-published reprint of a manifesto from 1990, Architecture: A Modern View, as well as Cities for a Small Planet and A Place for All People. There’s also the usual new releases and headlines. Happy reading!

Book of the Week:

Richard Rogers on Modern Architecture, by Richard Rogers (Buy from Thames & Hudson / from Amazon / from Bookshop)

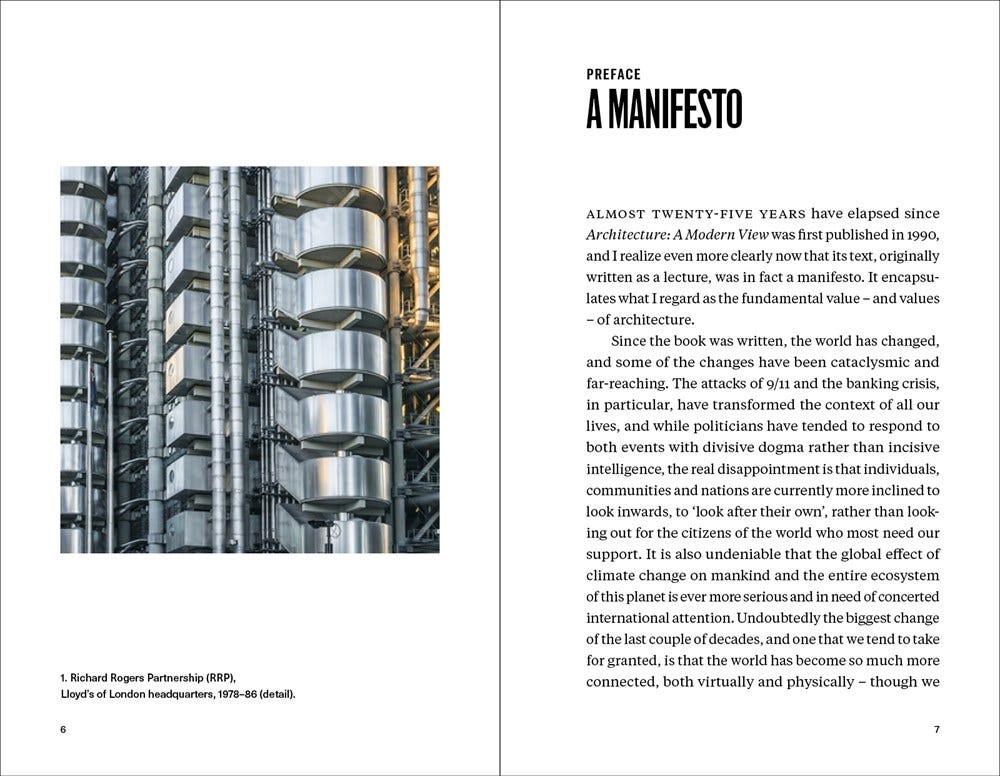

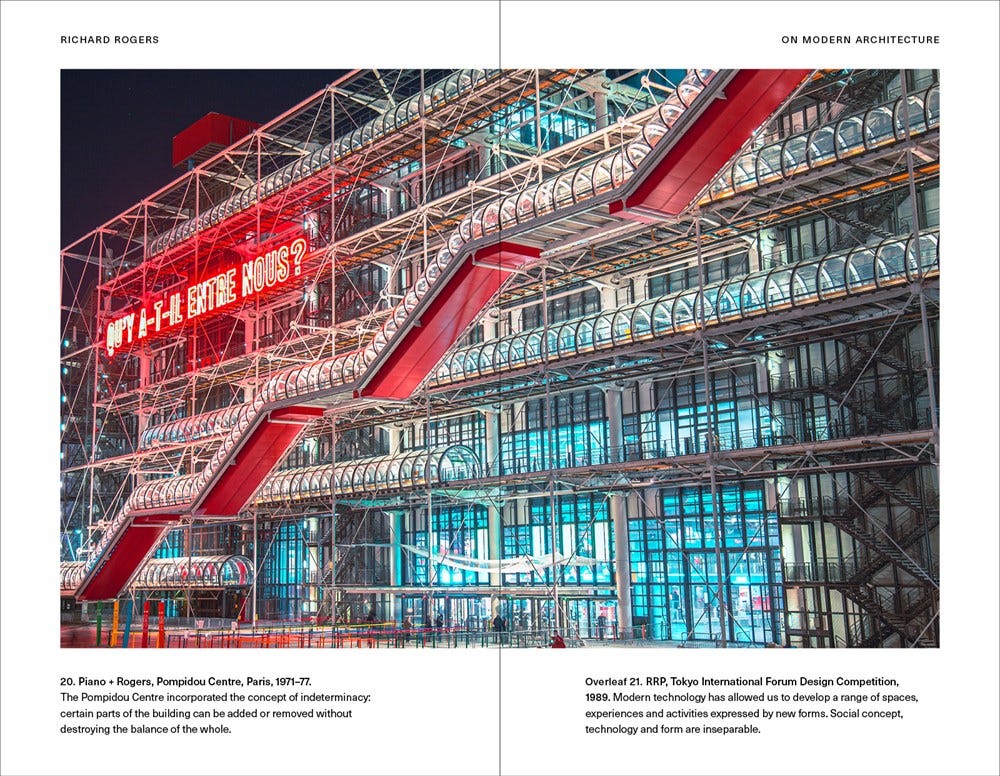

Last week saw the opening of Richard Rogers: Talking Buildings, an exhibition at Sir John Soane’s Museum London that “celebrates Richard Rogers as more than an architect, creating a vivid and immersive portrait through exploration of his far-reaching influence as a thinker, campaigner, humanist and activist.” Known for his celebrated high-tech architecture, most notably the Centre Pompidou (with Renzo Piano) and Lloyd’s of London, Rogers—who died in 2021 at the age of 88—was also outspoken in his embrace of social and environmental sustainability in architecture and urbanism, as evidenced in a small body of printed words. One of the first publications bearing his name was Architecture: A Modern View, published in 1990 from a lecture he gave the year before in celebration of Walter Neurath, a co-founder of publisher Thames & Hudson. Later books included Cities for a Small Planet and A Place for All People, whose titles capture his wider concerns (these two older books are at the bottom of this newsletter).

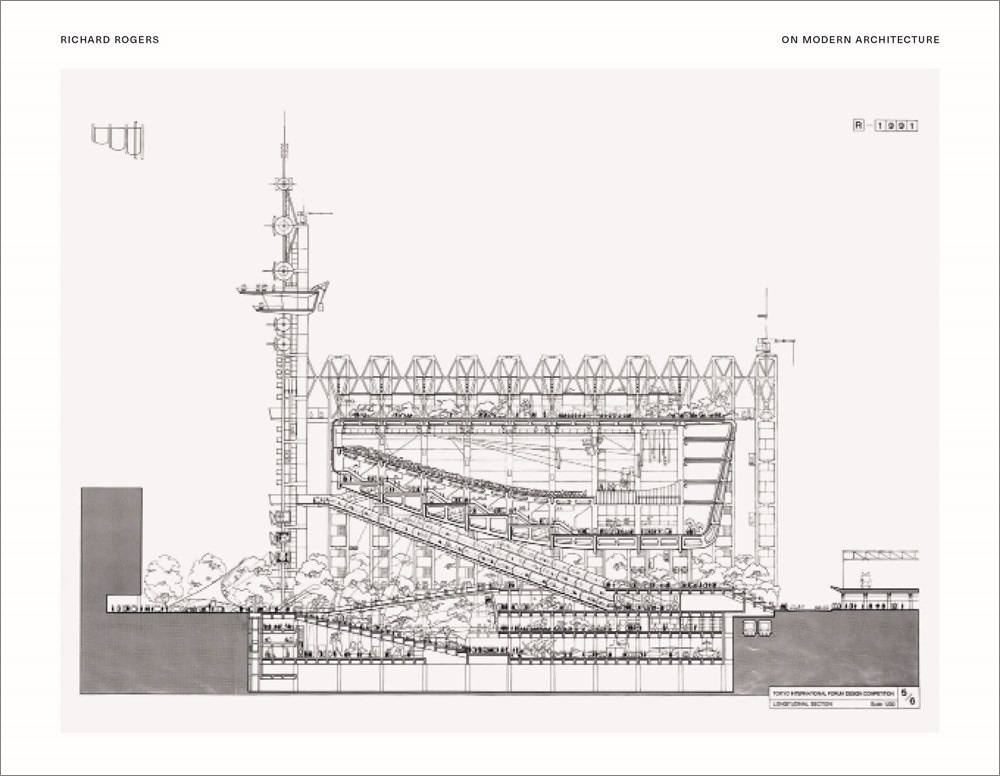

Possibly timed to the new Soane exhibition, this week sees the release of a reprint of the Neurath lecture, now given the title Richard Rogers on Modern Architecture.* It is the second reprint of the book, the first coming in 2013, coinciding with the Royal Academy in London mounting Inside Out, a major retrospective of Rogers’s career. At that time, Rogers added a short preface to the Neurath lecture, also included in the latest reprint (above spread); he described the publication as “a manifesto” that “encapsulates what I regard as the fundamental value—and values—of architecture.” If it is in fact a manifesto, it is a short one, with just 21 pages of text across the book’s 72 pages. These numbers make it comparable to Michael Benedikt’s “extended essay” For an Architecture of Reality, published in 1987, which is 80 pages but has text on only around a quarter of those pages. In both cases the short lengths are appealing, because the words are digestible in one sitting, the images add to the arguments, and the texts are perfectly suited to students, regardless of the fact they are now 35-plus years old.

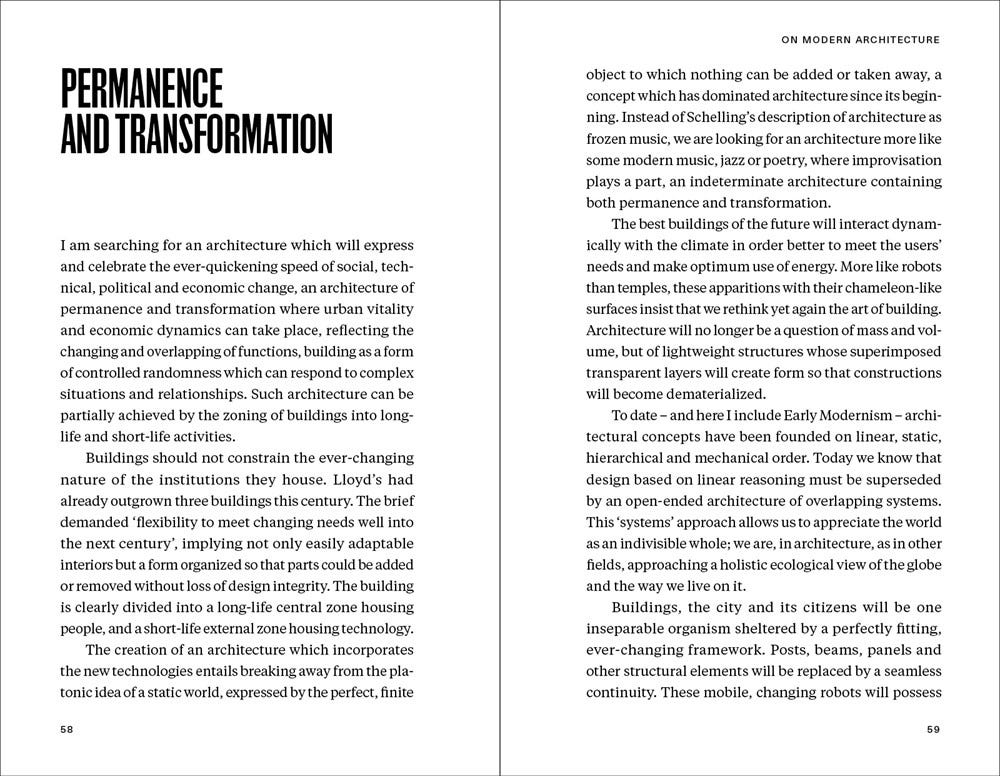

Rogers’s manifesto is organized into four short chapters: “A Modern View,” “The Business of Architecture,” “Innovation and Exploration,” and “Permanence and Transformation.” I find the second chapter the most relevant, not only because it finds Rogers at his most critical, but because it still resonates today, 35 years later. While the most vocal critics of modern architecture, such as Prince Charles in Rogers’s day and Justin Shubow in the United States today, blame architects and planners for wrecking cities and landscapes, Rogers contends that “it is nonsense to suggest that the ideas of the Modern Movement can be held principally responsible for the despoliation of our cities.” Who then is to blame? One answer is the clients: “[One] of the most important aspects of our public life—our architecture—has been sacrificed to the private interests of the market and the short-sighted economies of public officials.”

But clients are not solely to blame, for Rogers then lambasts architects who “have been too ready to collude with their clients in the view that architecture is just another profitable business with no bearing on the public at large.” Rogers, to reiterate, was saying these words in 1989, as neoliberalism was spreading, solidifying architects as service professionals whose value was in creating brandscapes rather than social spaces. Although this is a simple argument, it’s one I tend to agree with, even today, when discussions of architectural style appear to have trumped (pun intended) other concerns, such as sustainability, social equity, and even architectural creativity (have you seen those lackluster Grand Penn renderings?!). Yes, architecture is a business—and Rogers’s various partnerships, living on in RSHP, are examples of successful ones—but it is one whose concerns and responsibilities are so much broader than just the bottom line; the best architects, even if they don’t win awards or have monographs to their name like Rogers, are well aware of this.

*Richard Rogers on Modern Architecture is part of Thames & Hudson’s “Pocket Perspectives” series, which consists of a dozen titles, as of now, on art and architecture, including John Boardman on the Parthenon, E. H. Gombrich on Fresco Painting, and Lucy R. Lippard on Pop Art. The short books are handsome hardcovers that should appeal to art lovers who like big ideas in small packages.

Books Released This Week:

(In the United States; a curated list)

A Moratorium on New Construction, by Charlotte Malterre-Barthes (Buy from The MIT Press [US distributor for Sternberg Press] / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Engaging with unsettling questions, A Moratorium on New Construction envisions a massive value shift for our existing stock. From housing redistribution to reinviting value generation, from anti-extractive measures to profound structural changes, from curricula reforms to purging the exploitative culture of the office, an entire rewiring of design processes and construction lays ahead.”

Architecture in the Age of Artificial Intelligence: An Introduction to AI for Architects (second edition), by Neil Leach (Buy from Bloomsbury / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “From ChatGPT and smart assistants to groundbreaking diffusion models for video and 3D modeling, this updated new edition investigates the profound effects of AI technologies on architectural practice.” (My review at World-Architects)

Architecture of Segregation: The Hierarchy of Spaces and Places, by Jeff McCants (Buy from Two Penny Publishing / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “This groundbreaking work delves deep into the historical contexts of segregation, from the indigenous peoples of North America to the African diaspora through the Triangular Slave Trade, uncovering how architecture played a pivotal role in the subjugation of marginalized communities.”

American Icons Volume 2: Building the Nation: Transformations and Resilience, edited by Sam Lubell and gestalten (Buy from gestalten / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Building on the foundation laid by American Icons, American Icons Volume 2 continues the exploration of American architecture, chronicling its evolution and the iconic structures that define the nation’s skylines.”

Programmed for Hope: Architectural Experimentation at the HfG Ulm Building Department, edited by Chris Daehne, Helge Svenshon and Martin Maentele (Buy from ACC Art Books / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “This book traces the legacy of the Department Building at the Ulm School of Design, where experimentation and intellectual rigor redefined modern architecture. Rooted in critical thinking and knowledge exchange, it brought together design, science, and creativity to address architecture’s complex challenges.”

Stanley Tigerman: Drawing on the Ineffable, edited by George Papamattheakis (Buy from Yale University Press / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “This retrospective paints a new portrait of the legendary architect Stanley Tigerman (1930–2019) through his drawings, collages, and sketches.”

Full disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, AbeBooks Affiliate, and Bookshop.org Affiliate, I earn commissions from qualifying purchases made via any relevant links above and below.

Book News:

Two book features I wrote at World-Architects include a review of Neil Leach’s Architecture in the Age of Artificial Intelligence (the second edition is out this week) and a look inside Encounters, a book of Denise Scott Brown’s photographs (out in the US in August).

Political Histories, the tenth issue of gta papers—the open access publication of the ETH Zurich's Institute for the History and Theory of Architecture (gta)—is now available to read online. A contribution of relevance to this newsletter is “Political Ventriloquism: Andreas Papadakis’s AD in Thatcher’s Britain,” by Janina Gosseye and Léa-Catherine Szacka.

Nathan Silver, author of Lost New York (reprinted once or twice after its 1967 publication, and then expanded in 2000), Adhocism: The Case for Improvisation (1972, with Charles Jencks), and (befitting this week’s newsletter) a biography of the Centre Pompidou, died on May 19 at the age of 89. Read the New York Times obituary (gift link). Also of interest: When Silver was employed as an architect at Kramer & Kramer in the early 1960s, he helped design the Argosy Book Store’s home on East 59th Street, where it remains to this day.

Jackie Wullschläger and Edwin Heathcote have put together a list of the “Best summer books of 2025: Art, Architecture and Design” for the Financial Times.

Wanna read a monograph when you head to the beach? The editors of Architectural Record have rounded up the top ten monographs of the summer.

Graham McKay's 3rd Misfits’ Triennale—a roundup of select projects at ArchDaily "that made me stop scrolling for a minute or two"—has begun, with the House with a Small Library by Hiroshi Kinoshita and Associates standing out to me: a house with a street-level library open to the public—how generous!

From the Archives:

Pertaining to the Book of the Week, Richard Rogers wrote just over a handful of books in his lifetime (1933–2021), most of which were culled from lectures or related to exhibitions. Here are two of them, one based on a series of lectures, and one inspired by a major retrospective exhibition.

The BBC’s annual Reith Lectures, named for John Reith, the corporation's first director-general, began in 1948 with Bertrand Russell’s series of lectures on “Authority and the Individual.” The lectures are still going, and in its 75-plus years, only two architecture-related lectures are evident: Nikolaus Pevsner in 1955 and, to a greater degree, Richard Rogers forty years later, in 1995. The five-part lecture series by Rogers was titled “The Sustainable City,” and a couple years later it was made into the square-format paperback Cities for a Small Planet, the same title as the last of the five lectures. Fittingly, the book’s five chapters correspond with the five half-hour lectures broadcast on BBC’s Radio 4, all of which can be listened to online.

As edited by Philip Gumuchdjian, the book’s text departs slightly from the radio program, which I determined on a recent listen I made while following along with the book. Rogers’s words were edited slightly here and there, with some paragraphs shifted around and/or added as well. Most dramatic is that the book includes what the audio lectures, by definition, could not: images. Rogers had a good voice for radio, and as such I enjoyed the lectures, but architecture talks sans images are hard to pull off, so adding illustrations (drawings, diagrams, photographs, etc.) to the edited transcription makes perfect sense. They aid in understanding some of Rogers’s statements while also accentuating the most important points, especially when it came to his firm’s ambitious proposals for redesigning parts of London, the subject of the fourth lecture/chapter.

In 2013, the Royal Academy in London exhibited Inside Out, a major retrospective on Richard Rogers that “reveal[ed] the man and the ideas behind [such] pioneering buildings” as the Pompidou and Lloyd’s, and even included a full-scale prototype of his firm’s flat-pack housing in the RA’s courtyard. The exhibition was an inspiration for Rogers to collaborate with writer Richard Brown on A Place for All People: Life, Architecture and the Fair Society, published by Canongate in 2017, a book that is part autobiography, part monograph. On the personal side, readers learn about Rogers’s early years in Florence, his childhood dyslexia, his first wife, Su, and his second wife, Ruthie, among many other things. Though the distinction between personal and professional is often blurry (Su was a partner with Rogers and Piano on the Pompidou, for instance, and Rogers designed the River Café for Ruthie), which is befitting many architects and practitioners who treat architecture as their life. A third P could be added to personal and professional: political. Rogers was an outspoken humanist, an occasional protester, and even a political foe—remember his adversarial relationship with Prince Charles? Although parts of his life seem to have been remembered through rose-colored glass—or bright pink, rather, given his preference for the color—fans of Rogers’s markedly diverse buildings and the person behind them should find A Place for All People a compelling read.

Thank you for subscribing to A Weekly Dose of Architecture Books. If you have any comments or questions, or if you have your own book that you want to see in this newsletter, please respond to this email, or comment below if you’re reading this online. All content is freely available, but paid subscriptions that enable this newsletter to continue are welcome — thank you!

— John Hill