Show Me "Show-Me State" Buildings

Architecture Books – Week 37/2025

This newsletter for the week of September 8 heads to Missouri, the Show-Me State, to look inside—and use, given that I was there for part of my summer break last month—Buildings of Missouri, the latest guidebook in the Society for Architectural Historian’s Buildings of the United States series. The book From the Archive looks at an old book on the Library of Congress’s Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) that has ties to Osmund Overby, the posthumous coauthor of Buildings of Missouri. In between are two weeks worth of headlines and new releases. Happy reading!

Book of the Week:

Buildings of Missouri, by Osmund Overby, Carol Grove and Cole Woodcox (Buy from University of Virginia Press / from Amazon / from Bookshop)

Before even cracking open the cover of Buildings of Missouri, the latest book in the Society of Architectural Historians’ (SAH) Buildings of the United States (BUS) series, a curious thing is evident: Osmund Overby, the first of the three authors not listed in alphabetical order, died just over a decade before the book was released this March. Ozzie, as his friends called him, was a professor architectural history, past president of the SAH, and past editor-in-chief of the BUS series, which began in 1993 and was inspired and provoked by Nikolaus Pevsner and his Buildings of England series.

Overby wrote, co-wrote, and edited a number of publications on historical architecture in Missouri, among them histories of St. Louis’s Union Station, Laclede’s Landing, and Old Post Office, and a monograph on St. Louis architect William Adair Bernoudy. Overby’s focus on the state’s built environment led Missouri Preservation to create the Osmund Overby Award, which recognizes “published works that contribute to the documentation and interpretation of Missouri’s architectural history.” Karen Kingsley, the current editor-in-chief of the BUS series, describes in the book’s foreword how “Carol Grove and Cole Woodcox, with the help of other dedicated Missourians, were able to bring it to completion.”

“As well as writing the text for many buildings included in the book,” Kingsley also writes, “Ozzie determined the organization of the volume.” Accordingly, these became two areas I focused on as I started to flip through the book: seeing which projects were completed after Overby’s death in 2014, and seeing how the book’s organization helps (or hinders) how it is used as a guidebook. In terms of chronology, one would expect that a book produced by the Society of Architectural Historians would limit itself to old buildings, say from the 19th century and the 20th century. Appropriately, the majority of the buildings in the book date from these eras, but I was surprised to see numerous 21st-century buildings, both in the major cities of St. Louis and Kansas City and the smaller towns spread across the state.

My wife is from St. Louis, so I’ve been to the city a number of times, and I was pleased to see some of the many commendable contemporary buildings in this SAH guide: Tadao Ando’s Pulitzer Foundation for the Arts (2001) and its neighboring Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis (2003) by Brad Cloepfil; John C. Guenther's Alberici Headquarters (2004) in Overland; Fumihiko Maki’s Kemper Art Museum (2006) at Washington University; Citygarden (2009) by Nelson Byrd Woltz; David Chipperfield’s 2013 addition to the St. Louis Art Museum; and newer projects such as Jeanne Gang’s One Hundred apartment building (2020). Of course, as one would expect from any guidebook, even one clocking in and close to 600 pages, there are omissions. On the newer end, these include Adrian Luchini’s early childhood building for Harris-Stowe State University, Trivers’ Adam Aronson Fine Arts Center at Laumeier Sculpture Park, and the Kol Rinah Synagogue by Pattern Ives.

With another trip to Missouri taking place last month, I was able to use Buildings of Missouri as a guidebook, both ahead of the trip and while in the “Show-Me State.” Here, I realized how the geographical organization of the book worked well for planning itineraries but had a steep learning curve for people not familiar with all 114 counties in Missouri. Overby organized the book into nine regional chapters: two urban (St. Louis and Kansas City) and seven geographical (Mid-Missouri East, Mid-Missouri, Southeast, South Central, Southwest, Northeast, Northwest). Each chapter uses a two-letter designation that follows from the regional chapters (SL, KC, etc.), with the individual entries given a number: SL1 is Gateway Arch National Park, for instance, while KC1 is the Kansas City Water Department Building.

So far so good, but things get tricky with the ordering of buildings within each chapter. The urban chapters are okay, because they include maps, but the geographical chapters are organized by county in what appears to be counterclockwise order. Unfortunately, there are no county maps included in the book, and the map in the introduction that describes the nine regions has typos, where SE is used for Northwest and Southwest as well as Southeast. Knowing that our trip would take us outside of St. Louis, but not knowing, for example, where Camden Country is relative to Miller County or Osage County—or what geographical region any of these would fall into, or even knowing which towns are found in which counties—I ended up finding a county map online, printing it out, and marking it up with the chapter boundaries and (correct) two-letter designations. In an ideal world, such a key would be included in a guidebook.

Are my criticisms misguided? Are the books in the BUS series even meant to be used as guidebooks, or do they adopt the format to present as many buildings as possible and geographically situate them relative to each other? Back in 2018, I featured a couple SAH titles on my blog—one in the BUS series and one in their BUS City Guide series—and had similar comments to what I have written above. Curiously, all three books have a different size and format, which is also evident scrolling through SAH’s list of published BUS volumes. My impression is that the function of the publications as guidebooks is played down in favor of being comprehensive (if not exhaustive) surveys of buildings in a state and exhibiting the knowledge of their authors, in this case Overby, along with Grove and Woodcox who picked up where he left off.

Ultimately, the most helpful aid for me in navigating the hundreds of buildings in Buildings of Missouri was the index, which is nearly fifty pages long and is helpful in terms of names of architects and buildings, building types, and names of counties and towns. I was able to find many interesting buildings worth visiting on our trip, and I probably would have found even more if the book provided at least one photograph for every project given a two-letter/number designation. I probably would not have paid attention to the Harry S. Truman Visitor Center and Museum, if not for the photo (above) of its spaceship-like form perched on a bluff. I wonder how many buildings I passed over because the descriptions, though informative, failed to pique my interest as much as a (missing) photograph?

Books Released This Week (and Last Week):

(In the United States; a curated list)

A few books from the week of September 1:

The House of Doctor Koolhaas (Gumshoe #1), by Françoise Fromonot (Buy from University of Chicago Press [US distributor for Park Books] / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Gumshoe is a new series of architectural books that introduces an original approach to the writing of architectural history. Written by distinguished French architectural critic and historian Françoise Fromonot, the first case is about the Villa dall’Ava, a private residence in Saint-Cloud, a suburb of Paris.”

Richard Neutra and the Making of the Lovell Health House, 1925–35, edited by Edward Dimendberg (Buy from the Getty / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “This absorbing volume traces the Lovell Health House, designed and built by Austrian American architect Richard Neutra (1892–1970), from its inspiration through its construction to its impact.”

Nihon Noir, by Tom Blachford (Buy from powerHouse Books / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Tom Blachford’s cinematic photographs of Tokyo and Kyoto transport viewers to a futuristic, dystopian dimension, in which perpetual nightfall and neon-spotted cityscapes reign.”

A few books from the week of September 8:

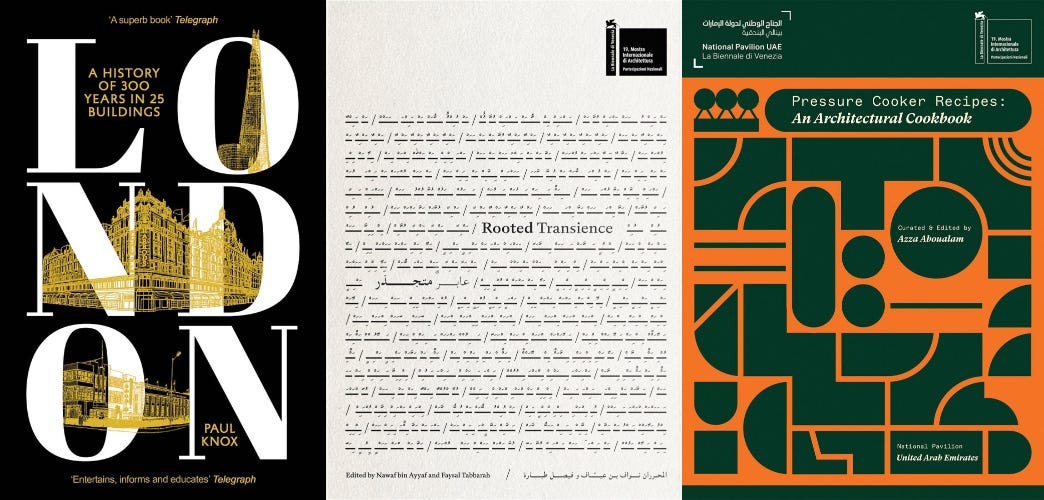

London: A History of 300 Years in 25 Buildings, by Paul Knox (Buy from Yale University Press / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “In this engaging study, Paul L. Knox traces the history of London from the Georgian era to the present day through twenty-five surviving buildings.” (This is a paperback edition of a book released in hardcover in 2024.)

Rooted Transience, edited by Nawaf Bin Ayyaf and Faysal Tabbarah (Buy from Artbook/DAP [US distributor for Kaph Books] / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “A collection of reflections on various architectural practices from the Arab world and beyond, on the occasion of the first AlMusalla Prize (2025 edition), an international architectural prize awarded for the design of a musalla in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.”

Pressure Cooker Recipes: An Architectural Cookbook, by X (Buy from Artbook/DAP [US distributor for Kaph Books] / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Architecture meets agriculture in this “cookbook,” published with The National Pavilion UAE – La Biennale di Venezia, that encourages sustainable practices in a desert region.”

Full disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, AbeBooks Affiliate, and Bookshop.org Affiliate, I earn commissions from qualifying purchases made via any relevant links above and below.

Book News:

PBS News has a story on “a new book [that] chronicles the indelible mark one family has left on American construction since the mid-1800s”: The Black Family Who Built America: The McKissacks, Two Centuries of Daring Pioneers (Atria/Black Privilege Publishing) by Cheryl McKissack Daniel.

The Graham Foundation has announced this year’s nearly forty new grants to organizations, some of them for publications and student-led journals. e-flux architecture has the announcement, with links to the awarded projects on the Graham Foundation’s website.

Alexandra Lange reviews Sam Bloch's Shade: The Promise of a Forgotten Natural Resource at Book Post, “a bite-sized book review newsletter sending subscribers well-made reviews by distinguished and engaging writers.”

ARA has an obituary on Manuel Gausa, a Spanish architect who co-founded Actar Publishers and directed the journal Quaderns. He died unexpectedly last month at just 66 years old.

Over at World-Architects, I wrote about Temporary Tecture: Structures of Necessity (JOVIS), a new book from KOSMOS Architects that “offers a fresh and compelling perspective on the often-overlooked world of temporary infrastructure.”

Architecture Exchange, a multimedia platform edited by Joseph Bedford and Matthew Allen, just released the first title in its new “Exchange Books” series: Smaller Architecture by Michael Meredith (MOS). The Architect’s Newspaper has a write-up, and Christopher Hawthorne reviews it at Punch List.

The authors of The Designs of Arne Jacobsen: Interiors, Furniture, Lighting and Textiles, 1925-1971 (Prestel) highlight “ten projects that showcase Arne Jacobsen's remarkable range” over at Dezeen.

Beaufort County's Post and Courier has an article on Contemporary Southern Vernacular: Creating Sustainable Houses for Hot, Humid Climates (Schiffer), a forthcoming book by Jane and Michael Frederick.

The latest book devoted to that love-it-or-hate-it style of architecture that is irresistible to publishers these days is Brutalist Interiors, edited by Derek Lamberton, published by Blue Crow Media, and featuring “contributions by leading architectural writers and historians" and "photographs by renowned photographers.” Find write-ups at Spaces and Wallpaper*.

I wonder if Frank Gehry, Rem Koolhaas, or the architects at MVRDV and Snøhetta would be flattered or insulted seeing their work in Weird Buildings alongside the Long Island Duck, the Longaberger Basket Building, and the Teapot Dome Service Station? We Heart has a preview of the book published by Hoxton Mini Press.

“The Architect as Writer: Expanding the Discipline Beyond Buildings”: Arch Daily’s overview of the role of books in architecture, from Vitruvius to contemporary publications.

From the Archives:

When trying to learn a little bit more about Osmund Overby, the posthumous coauthor of the Book of the Week, I found a number of books from his library on the website of Columbia Books, an antiquarian bookstore in Columbia, Missouri. Overby was a longtime professor at the University of Missouri and resident of Columbia, so it makes sense that many books from his library made their way to the bookstore after his death in 2014. I stopped by the bookstore while in Missouri last month and opted to pick up one of his ex libris books: Wisconsin Architecture, a survey from the Library of Congress’s Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) with the lengthy subtitle A Catalog of Buildings Represented in the Library of Congress, with Illustrations from Measured Drawings.

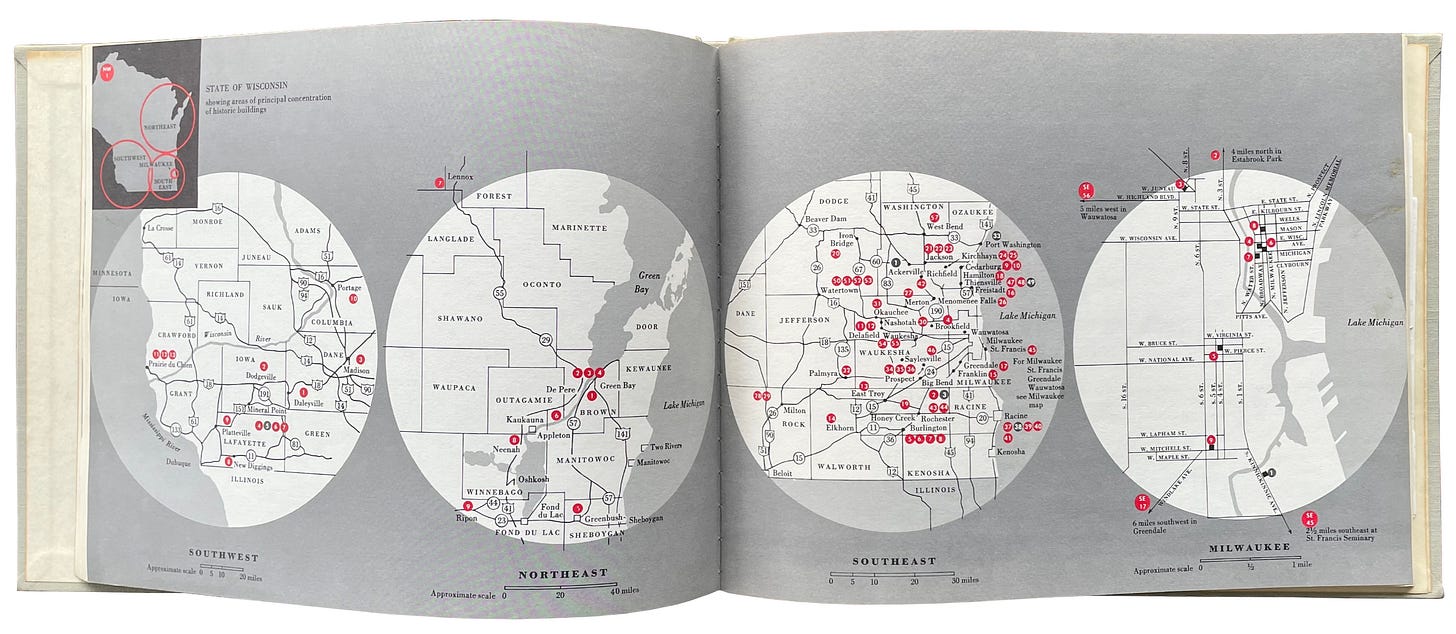

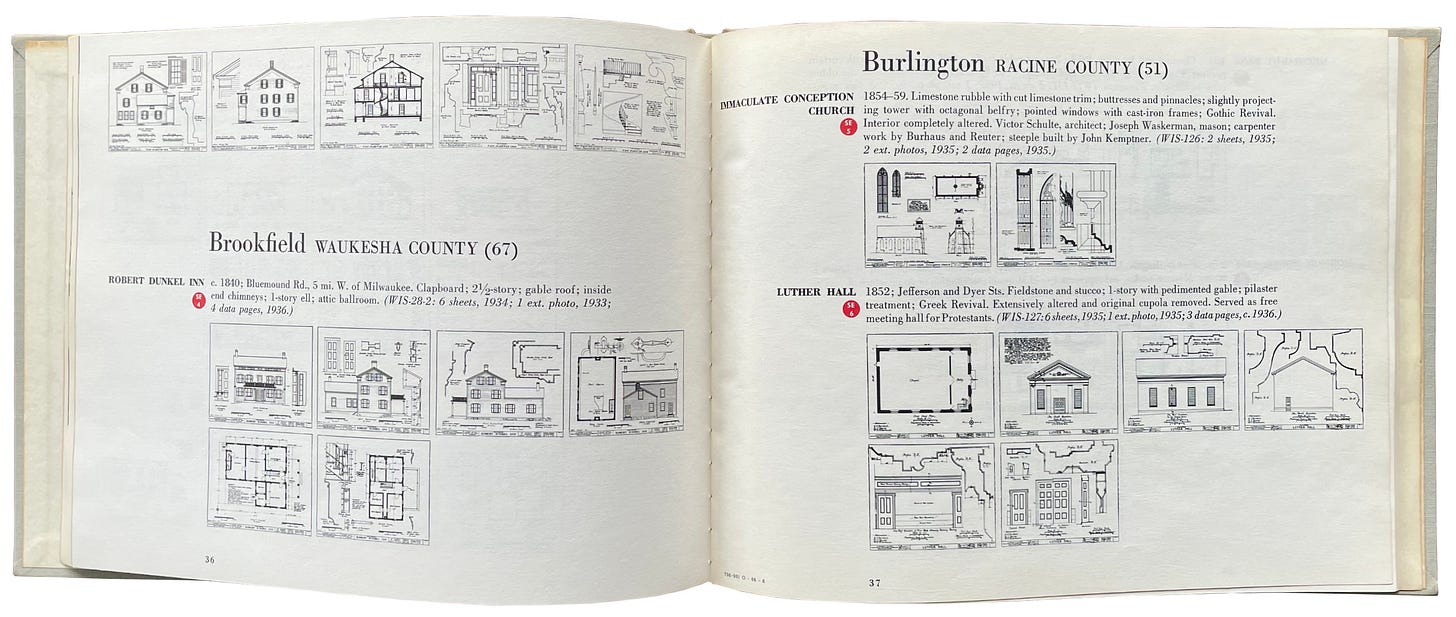

By coincidence, the book—written by Richard W. E. Perrin and published in 1965 by the US Department of the Interior and National Park Service—bears some similarities with Buildings of Missouri, at least in terms of its organization. The now sixty-year-old book acts as a guide to the buildings in Wisconsin in the HABS collection and, like the Book of the Week, is structured by region. The spread below shows the four main “areas of principal concentration of historic buildings” (Southwest, Northeast, Southeast, and Milwaukee), complete with letter/number designations: SW1, NE10, M9, etc.

Instead of organizing the dozens of buildings into four corresponding chapters, the buildings are mixed together, presented alphabetically by town/city, from Ackerville to West Bend. Information is basic, with project data, some formal and material descriptions, location details for the drawings in the Library of Congress’s collection, and small thumbnails of the drawing sheets.

Clearly, the book—part of a series highlighting resources in HABS—was meant to aid researchers who could then access the original drawings and other materials at the Library of Congress archive in Washington, DC. Today, sixty years later, with HABS also encompassing the Historic American Engineering Record and Historic American Landscapes Survey, such archival materials are found online, many of them digitized in high resolution. (Find here, for example, the drawings for Robert Dunkel Inn, the same half-dozen drawings of which are visible on the verso page above.) As such, this book is a relic of another era, though one not far off, and one whose organization and design still provides lessons to bookmakers today.

Thank you for subscribing to A Weekly Dose of Architecture Books. If you have any comments or questions, or if you have your own book that you want to see in this newsletter, please respond to this email, or comment below if you’re reading this online. All content is freely available, but paid subscriptions that enable this newsletter to continue are welcome — thank you!

— John Hill

Pressure Cooker Recipes: A Brutalist Cookbook.