This newsletter for the week of April 14 looks at two recently released reprints, both compact editions of books published decades ago: Outrage by Ian Nairn and Fantasy by Bruno Munari. Although these two books and their authors are considerably different from each other, the coincidental timing of their reprints has me thinking about the pros and cons of reprints in general. A couple related books from the archive are at the bottom of this week’s newsletter, while the usual headlines and new releases are in between. Happy reading!

(Just a side note that, starting this week, I’ve decided to flip the title and subtitles of my weekly newsletters, partly so they are (hopefully) more interesting when they land in your inboxes, and also so they don’t look so repetitive and indistinguishable from each other on the main page of this newsletter.)

Books of the Week:

Fantasy: Invention, Creativity, and Imagination in Visual Communications, by Bruno Munari. First published in 1977 by Editori Laterza as Fantasia. Invenzione, creatività e immaginazione nelle comunicazioni visive; reprinted in 2024 by Inventory Press. (Buy from Artbook/DAP [distributor for Inventory Press] / from Amazon / from Bookshop)

Outrage, by Ian Nairn. First published in 1955 by The Architectural Review; reprinted in 2025 by Notting Hill Editions. (Buy from NYRB [US distributor for Notting Hill Editions] / from Amazon / from Bookshop)

If there were the equivalent of a breakout album, film, or novel in the realm of architectural criticism, a likely candidate would be Outrage, a special issue of The Architectural Review from 1955, written by Englishman Ian Nairn (1930–1983) when he was just 24 years old. In it, Nairn, a former RAF pilot with no architectural qualifications, critiqued the planning and urban design of the countryside west of London, coining the lasting term “Subtopia,” which he defined as “the annihilation of the site, the steamrollering of all individuality of place to one uniform and mediocre pattern.” The successful publication pushed him into the spotlight and led to an editorial job at the Review, gigs hosting documentaries on UK television, and the making of around ten more books before he sadly drank himself to death at the age of 52. Nairn was a champion of the people and the enemy of modern planning and (bad) modern architecture, and his acerbic writing reflected that.

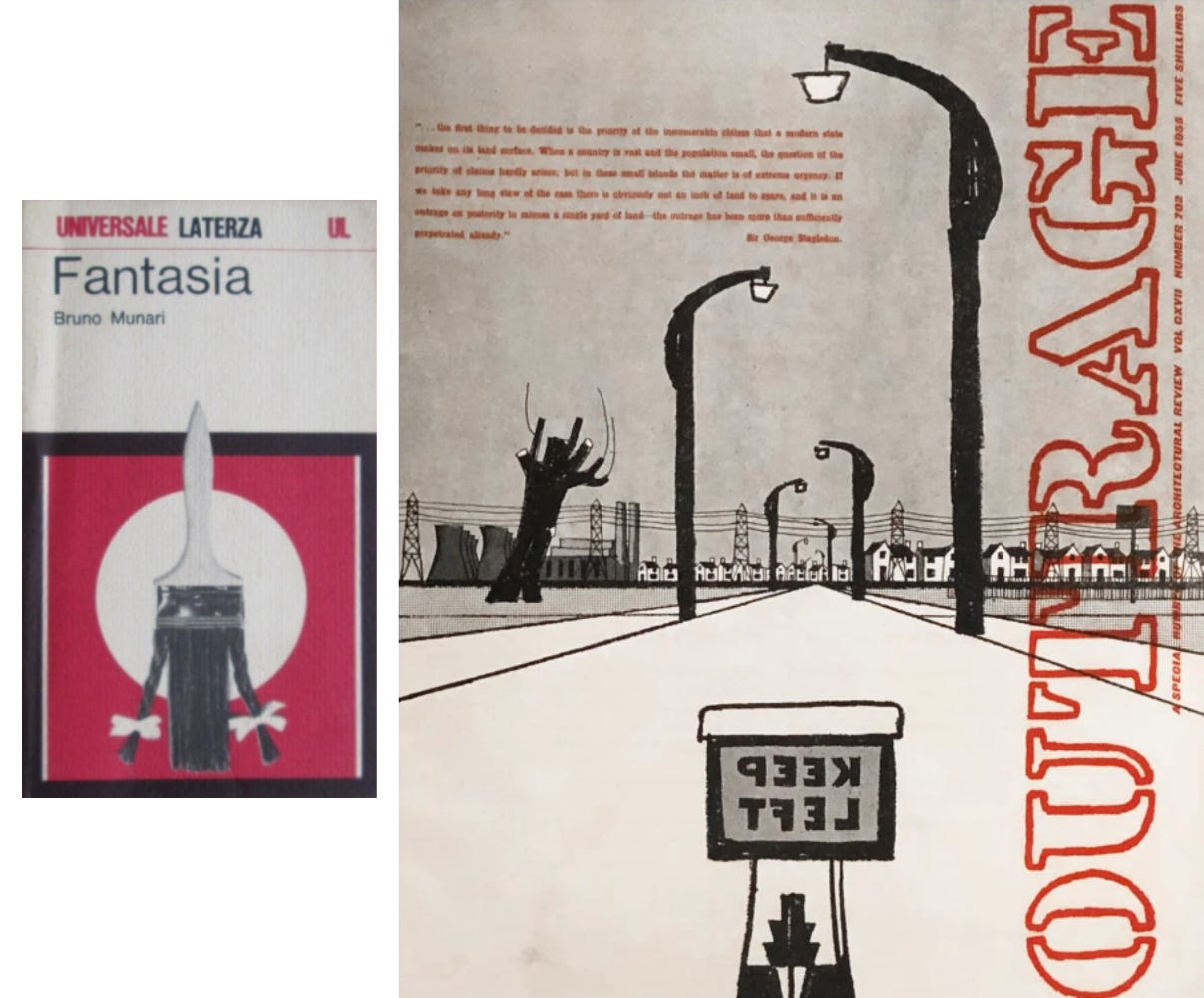

In contrast to Outrage, Italian artist and designer Bruno Munari (1907–1998) wrote Fantasia later in life, when he was in his seventies, making it the umpteenth book by the prolific maker of books for children and grown-ups. Fantasia is not as famous as Munari’s Design as Art, Circle Square Triangle, or Speak Italian, but that may stem from it not being translated into English until now, almost fifty years after it was first published. Fantasy finds Munari imparting his wisdom on readers by explaining his approach to fostering creativity and imagination, and inviting them to voyage along with him. Just as Nairn’s critical book finds relevance today because the countryside of England, like just about every country around the world, continues to be spoiled by ill-considered growth, the timing of Munari’s reprinted book finds humanity on the cusp of a creativity drain, as younger generations embrace AI over their own untapped creative faculties. By coincidence, each reprinted book is small, basically pocket-size (image above), but their originals are dramatically different from each other, with Outrage more than 12” tall and Fantasia just 7” tall:

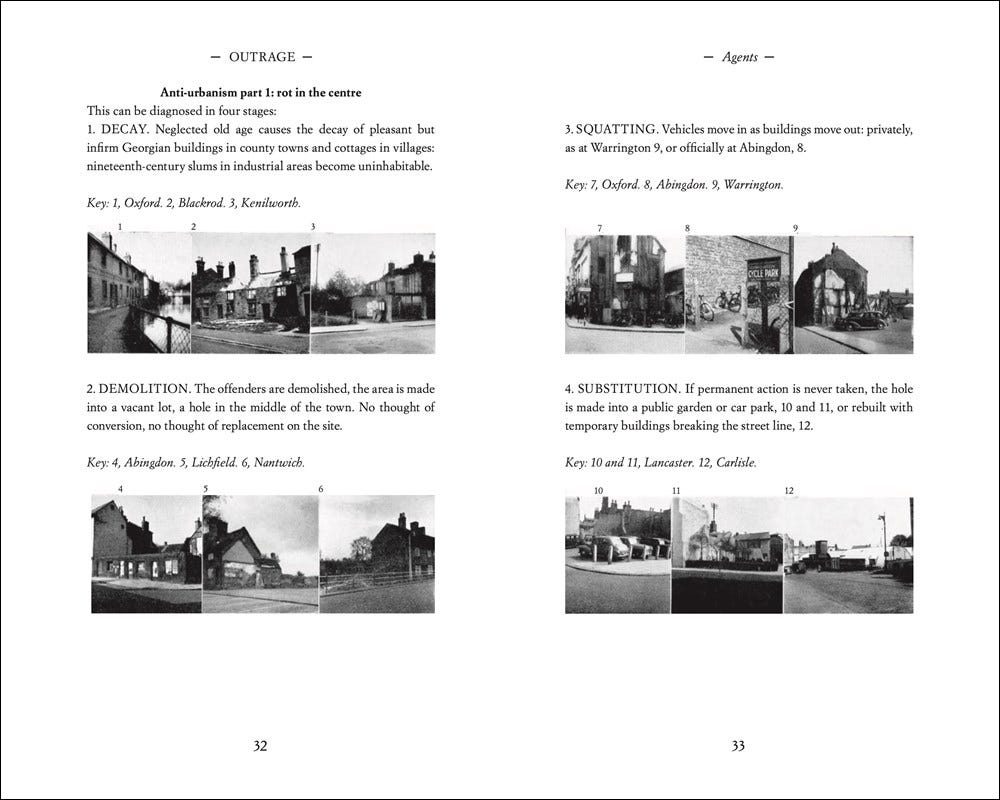

These differences (or not) between originals and reprints begin to get at some of the pros and cons of reprints. While the trim size of Fantasy is the exact same as its Italian original, the new edition of Outrage fits into the consistent format applied to every other hardcover published by Notting Hill Editions— including three others also written by Nairn. Not only does this downsizing mean Outrage’s page count of 92 is nearly double, the images that were sometimes generous in the original are often tiny in the reprint, some of them smaller than a postage stamp. Furthermore, the considered layout by Review editor Gordon Cullen of photos, drawings, and the bold use of color and smaller trim sizes for columns of Nairn’s text (see these features at Internet Archive) is nowhere to be found in the pocket-size edition from Notting Hill. This is a sad situation the publisher is well aware of, articulated by Travis Elborough in his introduction: “we’ve tried as far as possible to stay true to his original scheme […] albeit within the limits of our scale.”

Although it was a special issue of an architecture magazine and is remembered as a manifesto-like call to arms, the bulk of Outrage is basically structured as a guidebook. Nairn takes readers on a south-to-north road trip through England, from Southampton, near the English Channel, to Carlisle, just shy of the Scottish border, pointing out the views disfigured by electrical wires, signage, ugly light stanchions, and roadway clutter. While the small format of the reprint makes Nairn’s own often dark and high-contrast photos hard to decipher, Outrage is now small enough to easily take along with anyone who so desires to see how the countryside west of London has changed in the ensuing seventy years—for better or, unfortunately for Nairn, worse.

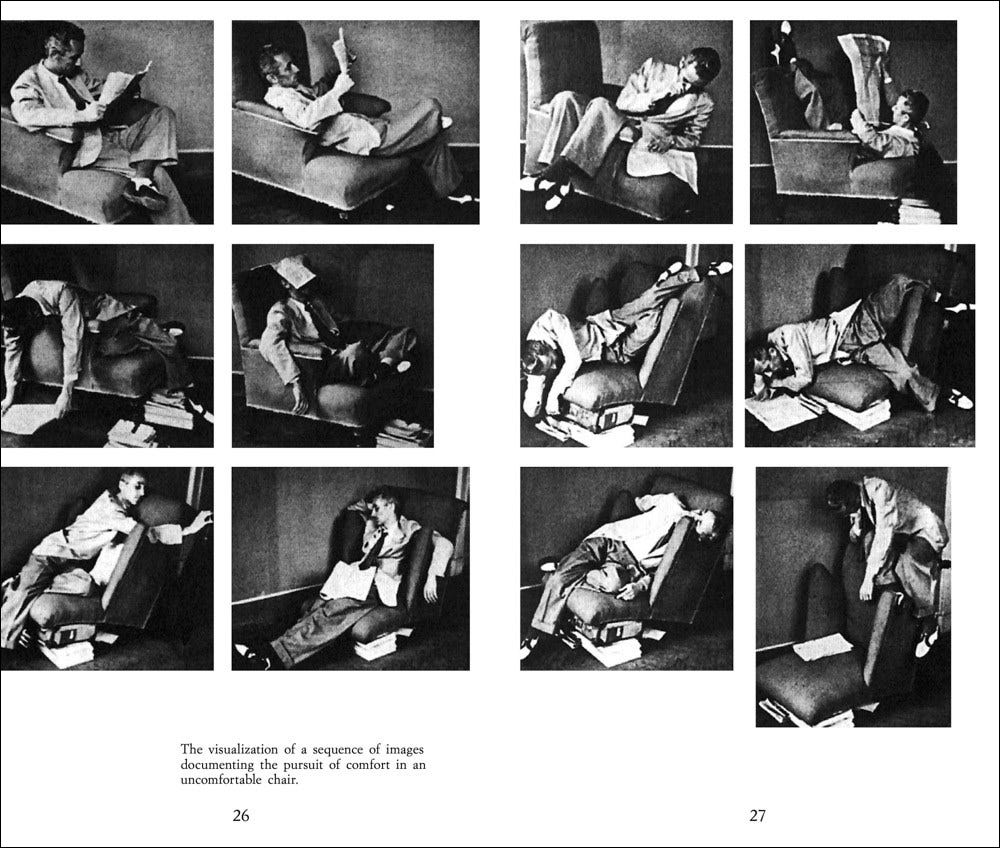

With its matching trim size and translation from Italian to English, Fantasy gets at the pros of reprints, notably maintaining the original design and giving the book a wider audience, even if it comes five decades after it was first published. The first is especially important, given that Munari’s designs of his books were integral to their appeal. Inventory Press notes at the back of the book that, even though “some design details may appear idiosyncratic to the contemporary eye,” the reprint was produced with “the intention of faithfully capturing the spirit of the original Italian edition.” The new cover, while it incorporates the image of a brush with pigtails, was designed by IN-FO.CO to depart from the Italian edition, since it was designed to fit within a series of books produced by Laterza. Contents aside (for now), I find the small book very well done: comfortable to hold and exuding Munari’s charms.

In regard to its contents, the obvious must be stated: clearly readers in 2025 are not the same as those in 1977. Munari’s approach to creativity based on the Reggio Emilia approach and the work of Jean Piaget, as stated on the back cover, may be out of step with some educators today (the audience I see benefiting the most from the book), and some of the names and references in Munari’s text may be unknown to people born in the decades since its initial publication. Aiding in these areas are annotations and a short essay at the back of the book, both by Munari scholar Jeffrey Schnapp. Among other things, he puts the book into the context of the Xerox-focused art Munari was creating at the time and the learning-by-doing method of art education that he trademarked. As such, Fantasia was not a standalone book when it was published in 1977; it was part of a wider effort on the part of Munari to foster creativity and free expression via particular exercises and teachable methods. Its value today, when fantastical visions are increasingly generated by AI bots rather than thinking and feeling humans, is obvious.

Books Released This Week:

(In the United States, a curated list)

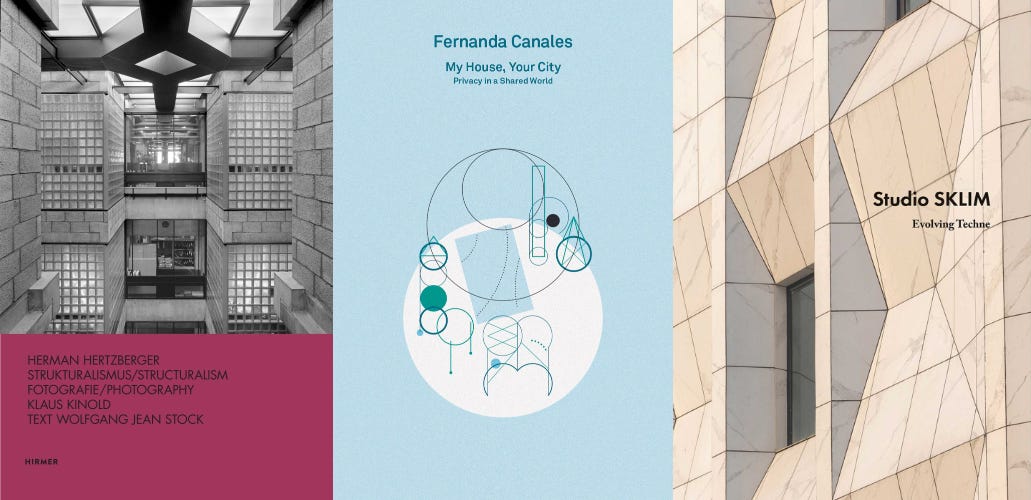

Hermann Hertzberger: Structuralism, by Klaus Kinold, with text by Wolfgang Jean Stock (Buy from University of Chicago Press [US distributor for Hirmer Publishers] / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “The award-winning photographer Klaus Kinold documents buildings designed by Hermann Hertzberger, one of the innovators of Structuralist architecture.”

My House, Your City: Privacy in a Shared World (2G Essays), by Fernanda Canales (Buy from Artbook/DAP [US distributor for Walther König] / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “The award-winning Mexican architect analyzes two centuries of residential architecture, tracing the environmental impact of housing.”

Studio SKLIM: Evolving Techne, by Kevin Lim (Buy from Images Publishing / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Provides a fascinating insight into the work of Singapore-based Studio SKLIM, an award-winning design firm that is skilled in crafting bespoke spatial solutions.”

Full disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, AbeBooks Affiliate, and Bookshop.org Affiliate, I earn commissions from qualifying purchases made via any relevant links above and below.

Book News:

Free tickets are now available for the Other Islands Book Fair, which Hyperallergic calls a “bringing together [of] over 40 independent publishers in a two-day event to engage in dialogue centered on making, cultural production, and graphic design.” It takes place place at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York, on Saturday, April 26, and Sunday, April 27. Reserve your times slot here.

Over at ArchitectureNow, Lynda Simmons reviews The Organizer’s Guide to Architecture Education, written by seven members of The Architecture Lobby’s Architecture Beyond Capitalism (ABC) School.

Kazys Varnelis reviews Abundance, the highly hyped new book by Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson, looking at it relative to Varnelis’s own 2008 book The Infrastructural City: Networked Ecologies in Los Angeles.

As reported by Fine Books & Collections, Artist Karen Wirth has two exhibitions of book arts inspired by architectural forms that just opened at the Minnesota Center for Book Arts in Minneapolis: Building/Books | Karen Wirth: A Retrospective Exhibition and Archabet: An Architectural Abecedarium.

From the Archives:

Related to this week’s Books of the Week are two other books by Bruno Munari and Ian Nairn, both A4/letter-sized:

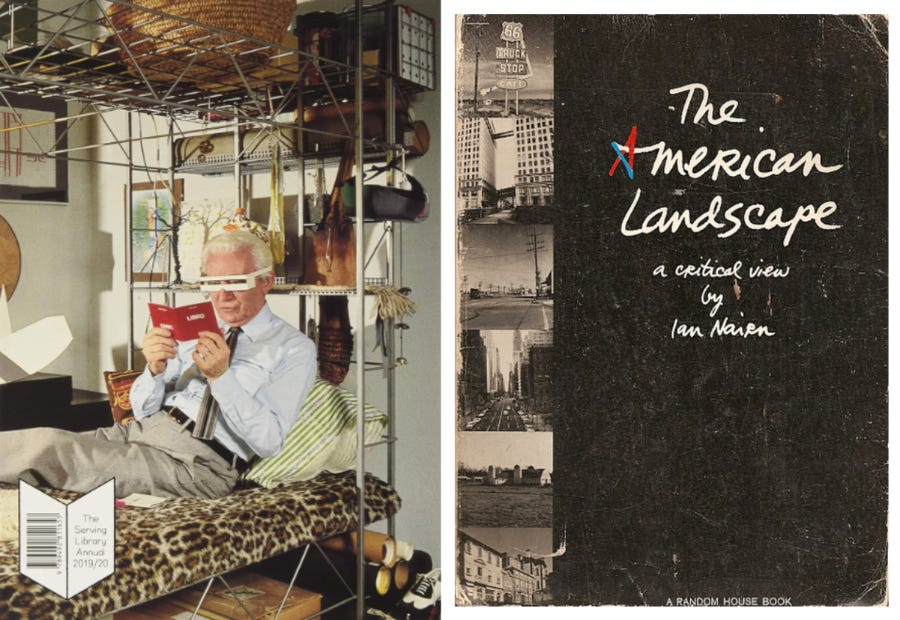

Another book by Bruno Munari that took decades to translate from Italian to English was Codice ovvio (Obvious Code), first published in 1971 and then reprinted inside The Serving Library Annual 2019/20. The Serving Library describes the original as “a modest portfolio of Munari‘s own writings, sketches and poems,” one they found important because “it brings together his often overlooked writing about and around those works.” So the non-profit decided to devote a special issue of its journal to its translation, reproducing the original’s paper size and design, down to the “unreadable book” of yellow lines on vellum sheets inserted in the middle. The disconnect between the book’s small trim size and the A4 journal results in wide margins that are filled on some pages by marginalia from dozens of contributors, living and dead. These additions are often illuminating, but occasionally they complicate one’s reading of Obvious Code; I could see Munari being happy with both results.

Though not a reprint, The American Landscape: A Critical View, published by Random House in 1965, is very much in line with Outrage, which it followed by ten years. The American Landscape documents Ian Nairn’s 10,000-mile, year-long trek through the United States via a Rockefeller Foundation grant he received in 1959. Applying the fury he previously focused on England’s “Subtopia” to the considerably larger American canvas, the book intersperses Nairn’s own photos with his observations, criticisms, and ideas on urban design. Actually, interspersing is the wrong word, since Nairn treats the photos like words, inserting them into paragraphs and even mid-sentence to make the visuals part of the book's grammar; this technique makes the book easy to read and weds the text and images unlike most books I’ve encountered, even Outrage. Sixty years after publication, the places he visited have changed significantly, and I'd wager most not for the better in terms of Nairn's principles; such is the difficulty with a townscape approach, which prioritizes visual experience and movement through space, on a country that values economy over aesthetics. Compared to Outrage, The American Landscape is unfocused by comparison, combining attributes of Gordon Cullen's Townscape with Peter Blake's God's Own Junkyard; Nairn biographers Gillian Darley and David McKie, in Ian Nairn: Words in Place (2013), attributed this to the British critic being “at sea,” far from the places he knew best, Subtopian warts and all. Nevertheless, Nairn's text is enjoyable and eye-opening at times, written with a skill that parallels the care he wanted to see in the environment.

Thank you for subscribing to A Weekly Dose of Architecture Books. If you have any comments or questions, or if you have your own book that you want to see in this newsletter, please respond to this email, or comment below if you’re reading this online. All content is freely available, but paid subscriptions that enable this newsletter to continue are welcome — thank you!

— John Hill