This newsletter for the week of April 28 looks at a new book on the life and career of Franklin D. Israel, who died in 1996 at the age of 50 with an influential body of work. Todd Gannon’s Franklin D. Israel: A Life in Architecture is Book of the Week, while a couple monographs from the early 1990s are pulled From the Archive. In between are the usual headlines and new releases. Happy reading!

Book of the Week:

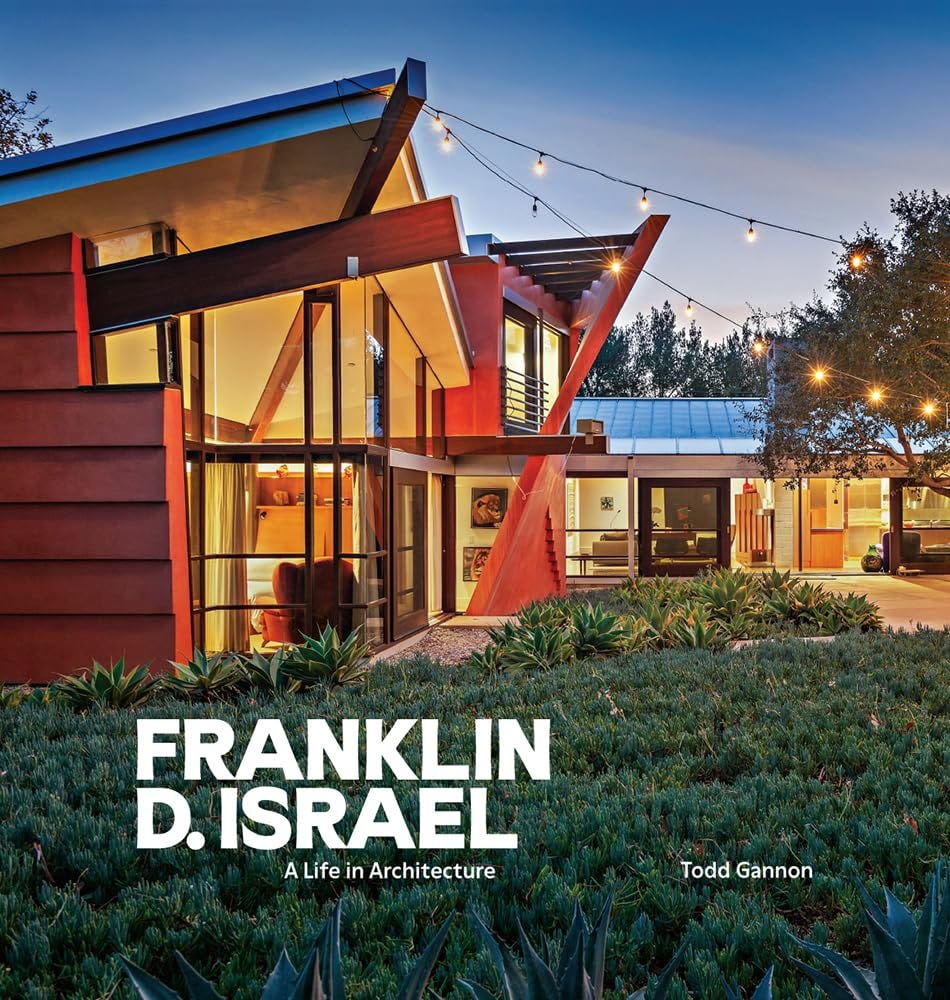

Franklin D. Israel: A Life in Architecture, by Todd Gannon (Buy from Getty / from Amazon / from Bookshop)

A few weeks ago, when I linked to a review of Todd Gannon’s Franklin D. Israel: A Life in Architecture, I was taken aback by the review’s labeling of Israel as an “underrecognized architect.” For me, educated in architecture in the early 1990s—when Israel was at his prime, when he was on the cover of magazines, and when multiple monographs of his were published—he was anything but unrecognized. My studio mates and I pored over the books on Israel (see two at the bottom of this newsletter), as well as those on Morphosis, Eric Owen Moss, and other Los Angeles contemporaries, finding inspiration but also absconding with some design motifs. (To wit, years later, when I happened to be working on a charrette in DTLA, one of the other architects in the office called my railing design “too Frank Israel.”) Given how big Israel was at the time, I was surprised to consider that roughly thirty years later he had slid into relative obscurity. It made me wonder: If Israel had not contracted AIDS and died in 1996 at the age of just 50, would he have had the prolonged fame of Frank Gehry, a mentor of his, or Thom Mayne, Moss, and other LA contemporaries still practicing into their eighties? Gannon’s book obviously does not answer such a rhetorical question, but it does illuminate much of the life that led to Israel’s dense body of influential architecture.

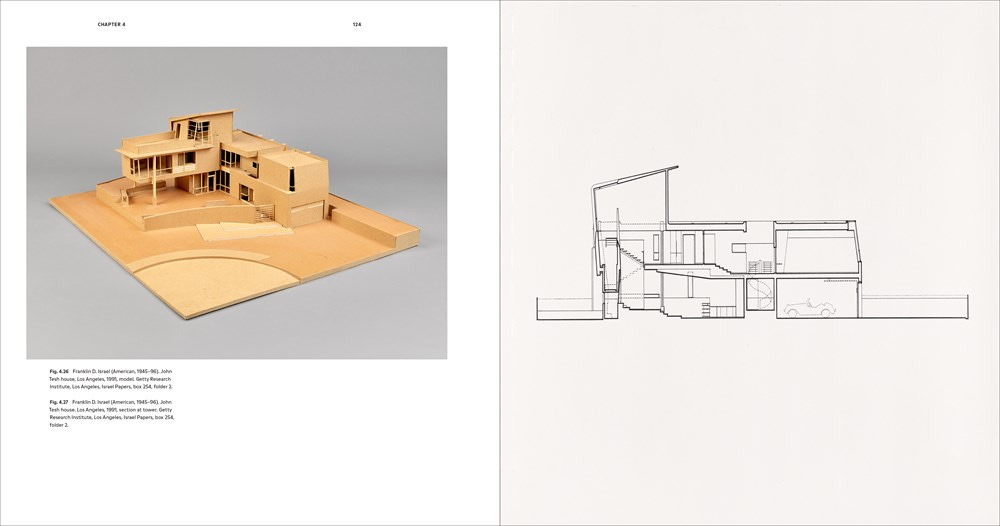

Gannon, an architect, professor at Ohio State University’s Knowlton School, and author of Reyner Banham and the Paradoxes of High Tech, has crafted a biographical monograph that melds a deeply researched and well told narrative with numerous images of Israel’s work, much of it culled from the architect’s sizable archive at the Getty Research Institute, which also published the book. Befitting a biography, the book’s seven chapters are in chronological order, from Israel’s upbringing in New York and New Jersey to his death in June 1996, though Gannon hops around in time within the chapters as needed, to stick with certain themes and personalities, and to tell a story that keeps the reader enthralled—this reader, at least. Gannon is not uncritical toward Israel’s architecture, but a deep appreciation of Israel’s talents during his brief but busy career permeates the book.

Having myself been drawn to Israel’s “mature” work in the early 1990s, I was pleased to learn about his peripatetic education, his years at the American Academy in Rome, and his early work, both as a set designer, albeit briefly, and as an architect. In regard to the last, I think it is hard to see projects like the Gillette Penthouse foreshadowing Israel’s exceptional work less than a decade later. That Israel was able to build a fair amount of residential and commercial work for rich and/or famous clients in a short amount of time arose as much from his latent design skills as from his outgoing nature, his ability to network, and a penchant for giving clients what they wanted.

Given that Gannon’s book melds biography and monograph, the former points to a necessary incorporation of context, character, and collaboration. Gannon delivers, discussing the AIDS crisis, Israel being an openly gay architect, the architecture scene in his adopted home of Los Angeles, the contributions of the architects in his employ (especially Barbara Callas, Annie Chu, and Steven S. Shortridge), and his personal and professional relationships, among the other things that permeated his roughly 25-year career. Coming to the fore for me was his relationship with Frank Gehry, sixteen years Israel’s senior, who like many LA architects moved there from elsewhere. By the time Israel had moved to LA in 1979 to teach at UCLA, Gehry was successful enough to turn down certain commissions and refer these clients to Israel, who seemed to be open to any commission, somewhat reminiscent of Frank Lloyd Wright.

Stemming from his ability to network, Israel also managed to be featured in competitions, exhibitions, and other venues where the participants he appeared alongside had clearly deeper portfolios. Still, these were opportunities he took advantage of, producing impressive work that helped develop his design skills that would lead to his later work. In particular I’m thinking of his participation in the Walker Art Center’s Architecture Tomorrow series, which began in 1989 and also featured Morphosis, Tod Williams and Billie Tsien, Stanley Saitowitz, Liz Diller and Ric Scofidio, and Steven Holl. In Six Mementos for the Next Millennium, Israel built six beautifully crafted boxes that overshadowed his works within. As Gannon writes, the installation “attracted critical attention to his work as never before.”

Gannon gives A Life in Architecture’s narrative a circular arc, discussing the 1996 exhibition Out of Order: Franklin D. Israel at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (MOCA) in the introduction and in the last chapter, “The End.” Additionally, Israel’s early experiences at Camp To-Ho-Ne, a progressive boys’ camp in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, recounted in the first chapter, “Charting a Course,” resurface in the penultimate chapter, “Leaving a Mark,” in Gannon’s description of Israel’s Dan House, which was built in Malibu in 1995 and was therefore the last design he lived to see completed. Also gracing the book’s cover, Gannon describes the project as “not a single building but a collection of cabins—maybe just a few tents—recently erected on a hillside clearing.”

Coincidentally, as Gannon’s book was getting ready to hit shelves in February, a massive wildfire hit Pacific Palisades and Malibu the month before, laying waste to full neighborhoods and destroying important works of architecture. While its neighbors burned, it appears the Dan House survived. This is ironic, given how Gannon’s tent-like comparison brings to mind fleeting architecture, and considering how Israel’s life and career were cut short at the age of 50. But it is also gratifying, given that the house is one of his last and most important works; knowing it survived means perhaps it will find a way to inspire younger generations of architects.

Books Released This Week:

(In the United States, a curated list)

Fire Island Modernist: Horace Gifford and the Architecture of Seduction (Expanded Edition), by Christopher Rawlins (Buy from Artbook/DAP [distributor for Metropolis Books] / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Featuring new houses, many additional photographs and a new afterword, Fire Island Modernist offers a fascinating look at the history and culture of this ‘gay paradise’ through the life and work of Horace Gifford.”

ARCH+: The Business of Architecture, edited by Anh-Linh Ngo, et. al. (Buy from Artbook/DAP [US distributor for Spector Books] / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “This publication examines the jobs, office structures and profitability in the field of contemporary architecture. It includes case studies of forward-looking business models from firms such as Assemble, Chybik+Kristof, Ana Filipovic and Space & Matter.”

The Urbanism Reader: Design, Technology, Culture and the Future of Cities, edited by Stefan Al and Tom Verebes (Buy from Bloomsbury / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Positioning design at the center of the debate, The Urbanism Reader brings together classic and contemporary readings to help designers understand the complexities of cities and urban design in the 21st century.”

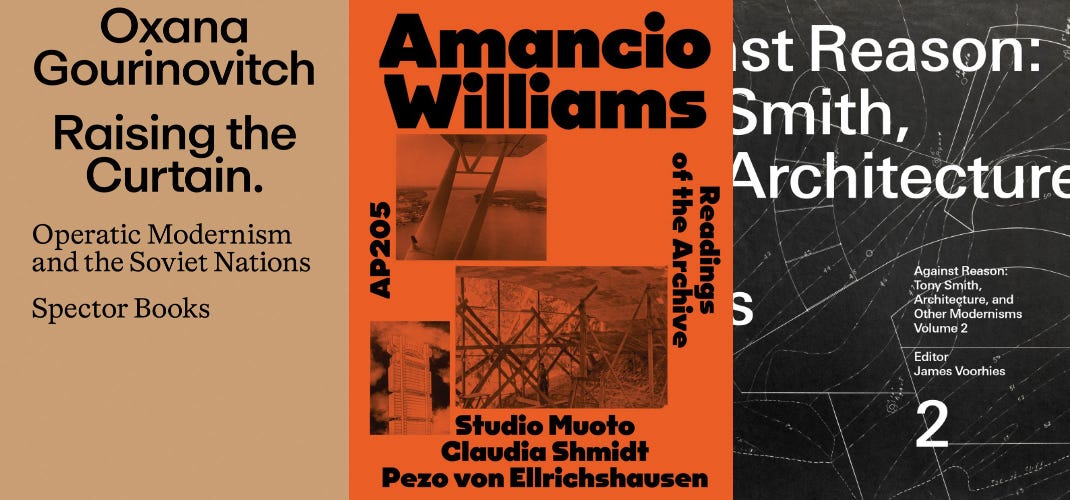

Raising the Curtain: Operatic Modernism and the Soviet Nations, by Oxana Gourinovitch (Buy from Artbook/DAP [US distributor for Spector Books] / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “This book revolves around two modernist opera theaters—each designed by a leading female architect—on the Soviet periphery, in Lithuania and Belarus. They are the Opera and Ballet Theatre in Vilnius (1962–74) by Nijole Buciute and the Comic Opera in Minsk (1973–81) by Oxana Tkachuk.”

Amancio Williams: AP205 – Readings of the Archive by Studio Muoto, Claudia Shmidt, and Pezo Von Ellrichshausen, edited by Francesco Garutti (Buy from Artbook/DAP [US distributor for Spector Books] / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — Argentinian architect Amancio Williams (1913–89) is best known for Casa sobre el Arroyo (now known as Casa del Puente, or Bridge House) in the province of Buenos Aires. This publication features research by scholars exploring his archive of it and other projects at the Canadian Centre for Architecture.

Against Reason, Volume 2: Tony Smith, Architecture, and Other Modernisms, edited by James Voorhies (Buy from The MIT Press / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Original essays and visual arts projects that explore the understudied breadth and richness of American artist Tony Smith’s work in architecture.”

Full disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, AbeBooks Affiliate, and Bookshop.org Affiliate, I earn commissions from qualifying purchases made via any relevant links above and below.

Book News:

Over at Architect’s Newspaper, Daniel Jonas Roche reviews Nora Wendl’s Almost Nothing: Reclaiming Edith Farnsworth, a critical “history of architecture, of women, and of glass” that recalls Eva Hagberg’s When Eero Met His Match: Aline Louchheim Saarinen and the Making of an Architect in the way the author inserts herself into the story.

Timed to Earth Day last week, The Architect’s Newspaper interviewed Charlotte Malterre-Barthes about A Moratorium on New Construction, which will be released in the US in June.

Ingrid D. Rowland explores Vitruvius’s Ten Books on Architecture, which has not gone out of print since “the papal printer Eucharius Silber brought out his edition in Rome in 1486,” in The New York Review of Books’ forthcoming Art Issue. (DM me if you don’t have a subscription but want to read this article; I’ll gladly email a PDF.)

From the Archives:

While Todd Gannon’s Franklin D. Israel: A Life in Architecture has visual documentation of numerous important works by Israel, both built and unbuilt, it still far short of what is presented in monographs. So people who want more information on Israel’s projects should consider these two monographs that were published in 1992 and 1994, respectively.

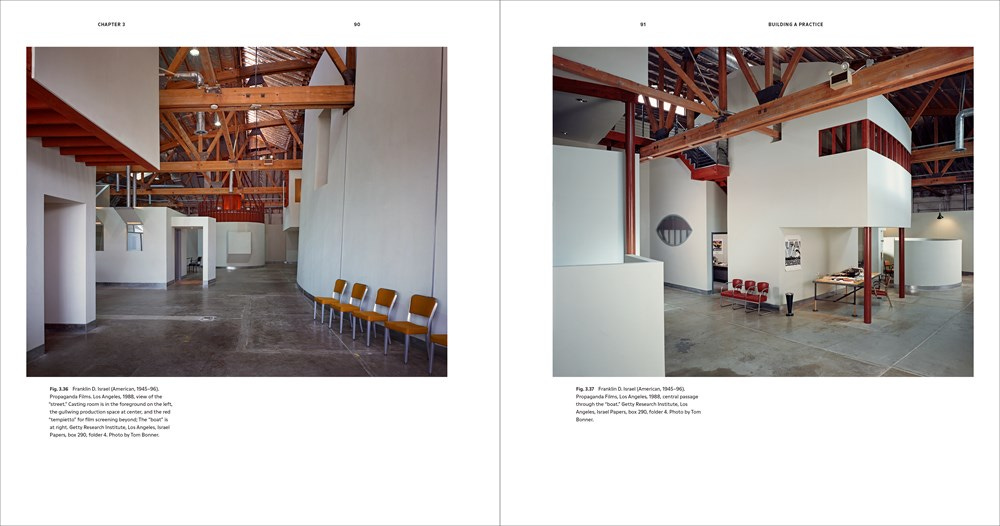

Franklin D. Israel: Buildings and Projects documents 30 projects spanning 20 years, from 1972 to the publication of the 224-page book by Rizzoli in 1992. Aligned with how Rizzoli was the go-to publisher for architecture monographs at the time, the projects are presented thoroughly and beautifully through photographs, drawings, models, and the architect’s own words. Logically, single-family houses are in abundance, but there is also in-depth documentation of a few offices he inserted into former industrial buildings in areas like Culver City—projects that brought Israel lot of attention and influenced other LA architects at the time. Bookending the chronological presentation of projects are an introduction by Frank Gehry and an essay by Israel at the front, and a biographical essay by Thomas S. Hines, then teaching architectural history at UCLA, at the back.

Two years later, in 1996, Academy Editions put out Franklin D. Israel, the 34th book in AD’s “Architectural Monograph” series. There is considerable overlap between the 15 projects in this 144-page book and those in the Rizzoli monograph, though at least one house moved from project to completion in those two years (Woo Pavilion), and one of Israel’s most famous houses entered the picture: The Drager House, in project form in these pages, would eventually be built and become the subject of a standalone monograph in Phaidon’s “Architecture In Detail” series. The biggest difference between these two monographs is AD’s layout, which in this period under editor Maggie Toy set columns of text at an angle to the page, layered drawings over photographs, and left very little white space on the page—it was an approach very much in line with Israel, Morphosis, and other architects practicing at the time.

Thank you for subscribing to A Weekly Dose of Architecture Books. If you have any comments or questions, or if you have your own book that you want to see in this newsletter, please respond to this email, or comment below if you’re reading this online. All content is freely available, but paid subscriptions that enable this newsletter to continue are welcome — thank you!

— John Hill

John...

Thank you for this post. I woke up this morning, read this post and it was so refreshing, the subject, Frank Israel, so my cup of tea. End result, I succeeded not to doomscroll, which is saying something in these times. Thank you for writing a sensitive, intelligent and over all interesting article about this book. I'm a few years your junior and I always hungered for more images, more buildings, more information from architects like Frank...

Thanks again for a malaise free morning...

-end of gush letter- :)