This newsletter for the week of May 13 heads to Switzerland — coincidentally right after the country won the Eurovision song contest. Take a look at the Swiss Architecture Yearbook 2023 and a pair of older books from the archive. In between are the usual new releases and headlines. Viel Freude beim Lesen!

Book of the Week:

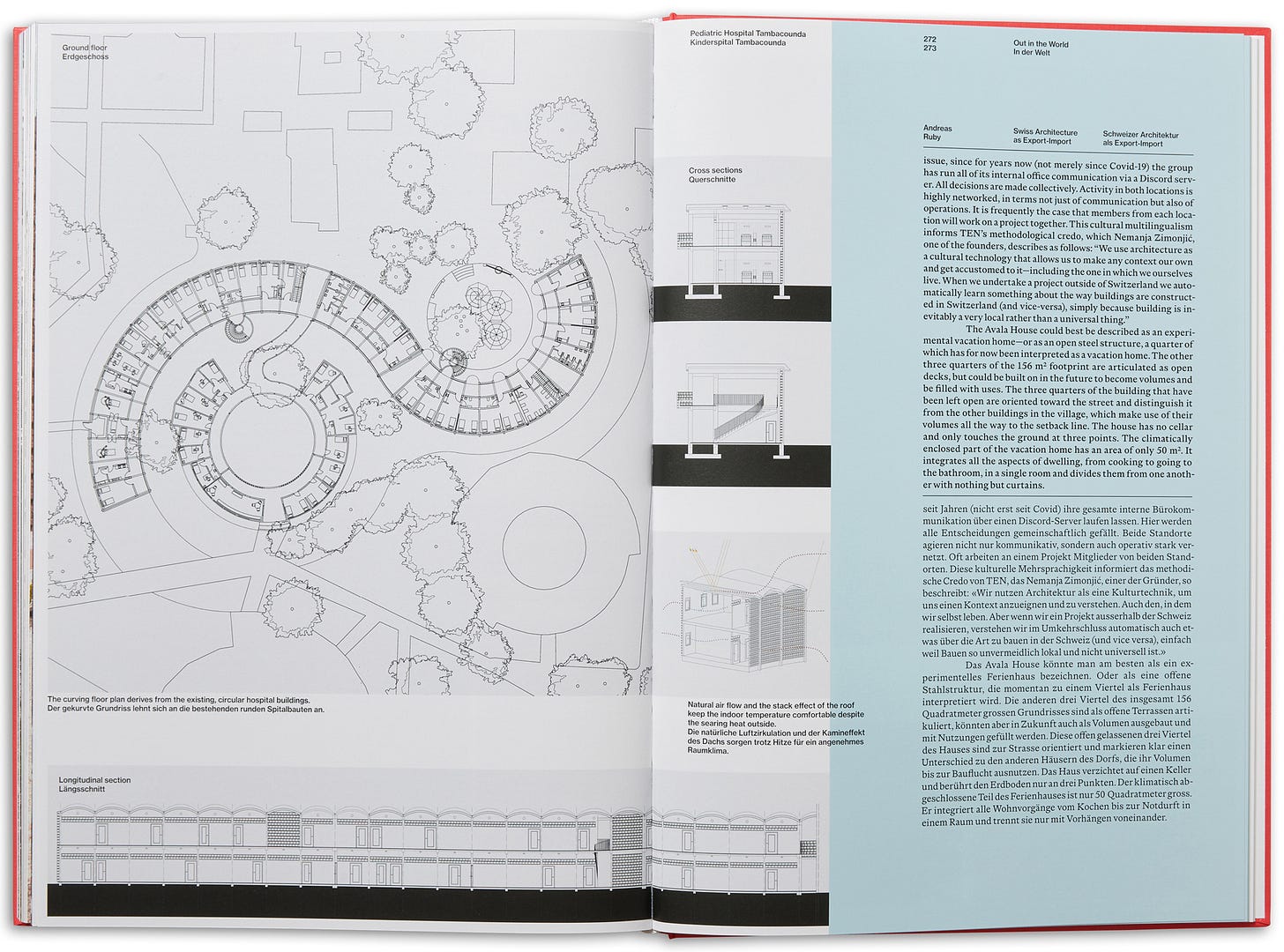

SAY 2023: Swiss Architecture Yearbook 2023 edited by Stiftung Architektur Schweiz SAS, Swiss Architecture Museum S AM (Andreas Ruby), and werk, bauen+wohnen (Daniel Kurz); published by Park Books (Buy from Amazon / Bookshop)

Although international architecture yearbooks were put out by various publishers starting in the mid-1990s, the architectural yearbooks that remain today are nationalistic in scope, put out by an institution or other body to share and promote, both internally and to the wider world, the best architecture of a particular country. The extant ones that come to mind are Architecture in the Netherlands, now in its 37th year, and the annual Spain yearbooks published by Arquitectura Viva. (Though no longer published, the annual yearbooks from Japan Architect also come to mind.) The architecture in these countries is prized by architects in other countries, though it is hard to say if these yearbooks played an integral role in that influence, or if they have merely been parts of a wider spread of each country’s architecture through global media. Another country whose architects and architecture are appreciated around the world is Switzerland, though its first yearbook arrived just last year (in January of this year in the US), courtesy of the Swiss Architecture Foundation (SAS), the Swiss Architecture Museum (S AM), and the journal werk, bauen+wohnen.

Andreas Ruby, director of S AM, and Daniel Kurz, former editor-in-chief of werk, bauen+wohnen, explain in their introductory essay for SAY 2023 some of the reasons why a Swiss architecture yearbook didn’t come sooner. In broadest terms, I’d contend the problem is Switzerland itself, a country with four national languages (French, German, Italian, and Romanch, all but the last the language of a neighboring country) and a politics defined by a confederacy of 26 cantons; these and other Swiss traits point to the importance of local and regional over national. Along these lines, Kurz and Ruby point out that “there is almost no country-wide architectural dialogue in Switzerland, but rather various conversations confined to the different local scenes,” while they also bemoan a “Made in Switzerland” view of the country by outsiders that “fails to reflect […] any sense of an identity that is composed from the polyphonic sound of many unique voices.” Via a logical and stringent selection process that is described after the essay, SAY 2023 strives to present those voices, even though such a process ends up reinforcing the conditions it tries to overcome: “The prominence of Basel, Geneva, and Zurich is evident,” they write, echoing how New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago would dominate a similar yearbook in the United States — if one were ever produced, that is.

Instead of presenting the 36 projects in geographical or typological chapters, the editors opt for nine thematic chapters, each one conveying an architectural approach that is foregrounded by Swiss architects, expressed via a parallel critical essay. The projects are described in the usual photographs, drawings, and brief texts from the architects on the majority of each spread, while the right third is home to the essay, clearly highlighted by a different background color for each chapter. The essays — by Ruby, Sabine Wolf, Bruno Marchand, and numerous others — serve to situate the projects within the themes: “climate-conscious construction,” “reclaimed spaces,” “village tales,” and so forth. English text is on the top half of the page, while the original, be it German, Italian, or French, is along the bottom. (This partially quadrilingual condition is echoed in the fact another introductory essay, by London’s Manon Mallord, is only in English.) While the themes that structure the book are hardly exclusive to Swiss architecture, the projects in the book point the way to some commendable means of addressing contemporary crises.

Books Released This Week:

(In the United States, a curated list)

Building for Everyday Life 2010–2025: Baumschlager Eberle Berlin edited by Gerd Jäger, Claudia Klein and Corinna Moesges, published by Birkhäuser (Buy from Amazon / Bookshop) — A monograph on the Berlin office of Baumschlager Eberle, which was founded in 2010 (the original BE was founded in Austria in 1985), featuring 40 projects spanning 15 years.

California Houses: Creativity in Context by Michael Webb, published by Thames & Hudson (Buy from Amazon / Bookshop) — This book surveys 36 houses built over the last ten years, houses that both “capture the spirit of California in distinctive ways” and “employ active and passive strategies to reduce their carbon footprint.”

Cities in the Sky: The Quest to Build the World's Tallest Skyscrapers by Jason M. Barr, published by Simon & Schuster (Buy from Amazon / Bookshop) — Barr, author of the thoroughly researched Building the Skyline: The Birth and Growth of Manhattan's Skyscrapers, branches out from NYC to London, Hong Kong, and other global cities home to the world’s tallest skyscrapers.

Concrete Architecture: The Ultimate Collection by Phaidon Editors, with Sam Lubell and Greg Goldin, published by Phaidon (Buy from Amazon / Bookshop) — A visual celebration of “might, majesty, and sculptural beauty of concrete buildings from all over the globe,” with 300 examples on 300 pages.

Sacred Modernity: The Holy Embrace of Modernist Architecture by Jamie McGregor Smith, published by Hatje Cantz (Buy from Amazon / Bookshop) — Modernist church spaces in the 20th century, from “Brutalism to Structural Expressionism,” are captured in McGregor Smith’s photographs.

Sir Edwin Lutyens: Britain’s Greatest Architect? by Clive Aslet, published by Triglyph Books (Buy from Amazon / Bookshop) — Who better to take readers on “the journey behind the buildings designed by Lutyens” than Aslet, chairman of the Lutyens Trust.

Full disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, AbeBooks Affiliate, and Bookshop.org Affiliate, I earn commissions from qualifying purchases made via any relevant links above and below.

Book News:

With better timing than me (I reviewed it in February, in Week 9/2024), Oliver Wainwright looks at Protest Architecture: Barricades, Camps, Spatial Tactics 1830–2023 in the context of the pro-Palestinian protests that spread across university campuses.

Raymond Fung Wing-kee’s new book, Untold Stories: Hong Kong Architecture, “sheds light on 70 local buildings and urban spaces designed by Hong Kong architects.”

Who knew there was a “Champaign School of Mid-Century Architecture”? I surely didn't. Mid-Continent Modern: The Champaign School of Mid-Century Architecture, being celebrated this week, documents some of the work designed by architects “keenly aware of the prairie landscape of Central Illinois.”

From the Archives:

In their introductory essay in SAY 2023, Kurz and Ruby touch on “the group of architects who helped Swiss architecture to international fame in the 1980s and 1990s,” among them Peter Zumthor and Herzog & de Meuron, lamenting that the generation of their successors “has not managed to develop the same kind of international recognition.” Was the fame decades ago a one-time phenomenon, a convergence of the right ideas finding the right expression by the right architects in the right time and place? In many ways it was, and there's no better analysis of Swiss architecture in that period (by architects in the German-speaking cantons, at least) than Irina Davidovici’s Forms of Practice: German-Swiss Architecture, 1980-2000, the second edition of which I reviewed in 2019. With eight case studies of notable buildings designed by Zumthor, HdM, Gigon / Guyer, Valerio Olgiati, and others, I called it “an important book for fans of Swiss architecture.”

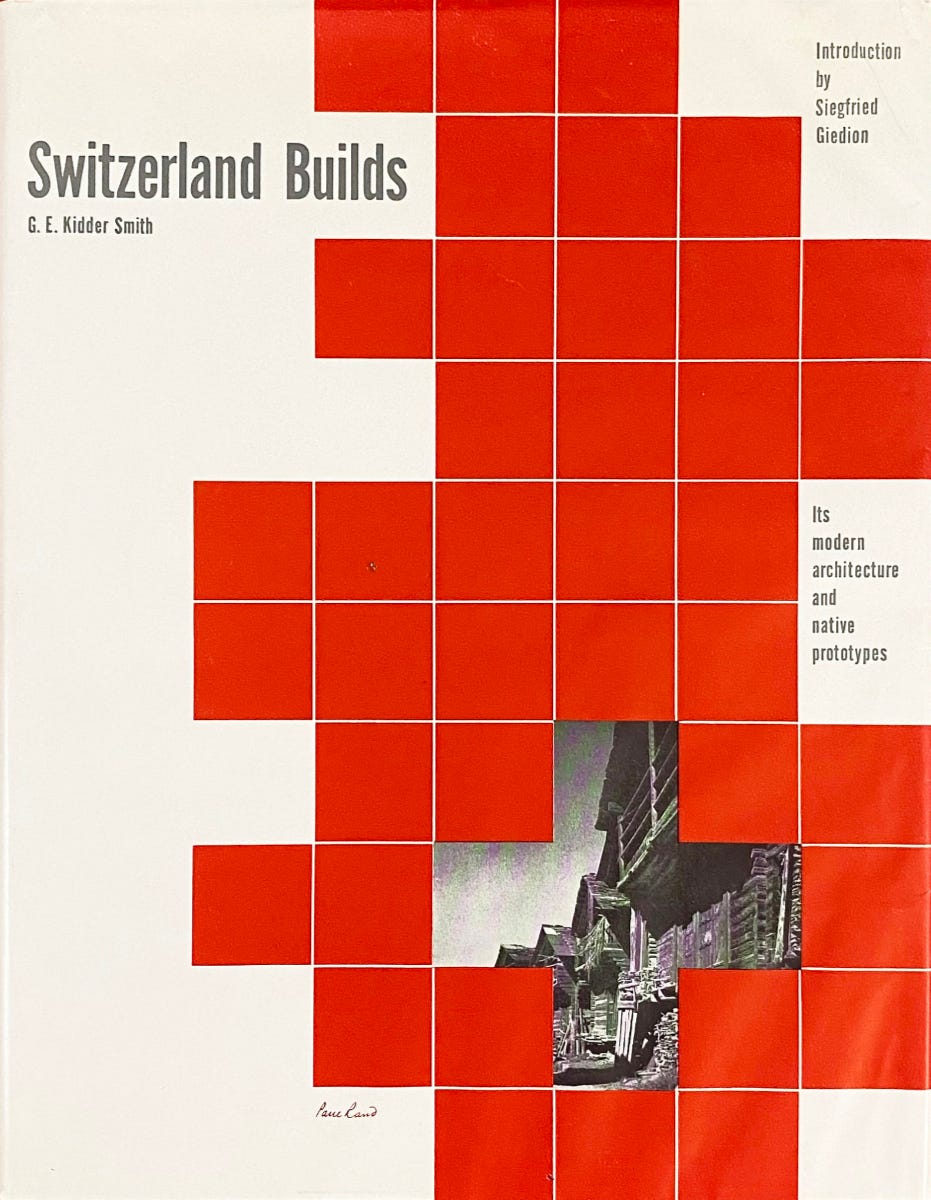

What about Switzerland before the fame of the 1980s and 90s? Decades earlier, in the first of G. E. Kidder Smith’s three “Build” books, published in 1950, Switzerland Builds: Its Modern Architecture and Native Prototypes provided an expansive visual presentation of the country’s architecture, from the vernacular to the modern. Old and new comprise the two halves of the book, with “Native Architecture” presented geographically and “Modern Architecture” presented typologically: housing, churches, schools, etc. “Although Kidder Smith’s book was not conceived as a marketing tool,” Angelo Maggi writes in G. E. Kidder Smith Builds (ORO Editions, 2022), “it nevertheless became an instrument capable of enhancing Swiss cultural promotion abroad.” Even so, many of the architects in Switzerland Builds are little known today, far from the familiarity of a Zumthor or a Herzog & de Meuron, making the nearly 75-year-old book one of discovery as much as SAY 2023.

Thank you for subscribing to A Weekly Dose of Architecture Books. If you have any comments or questions, or if you have your own book that you want to see in this newsletter, please respond to this email, or comment below if you’re reading this online. All content is freely available, but paid subscriptions that enable this newsletter to continue are welcome — thank you!

— John Hill