This newsletter for the week of July 22 heads to Urbino, the Italian hill town that architect Giancarlo de Carlo devoted much of his career to. His work there is the subject of the “Book of the Week,” while a couple of related books touch upon the same. In between are the usual new releases and book headlines. Happy reading!

Book of the Week:

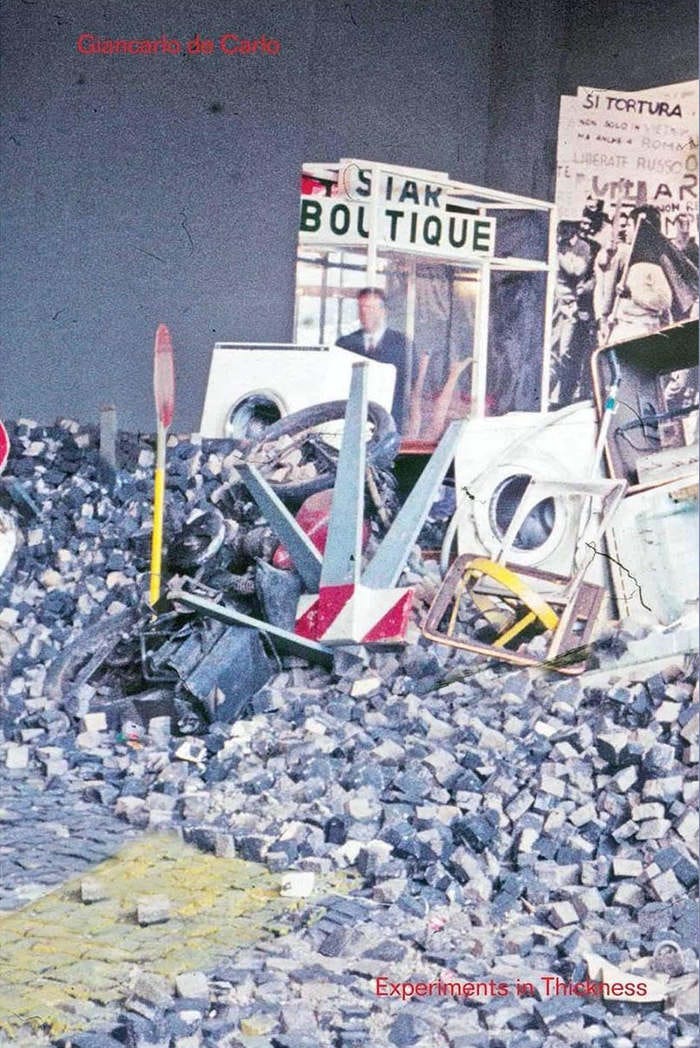

Giancarlo de Carlo: Experiments in Thickness edited by Kersten Geers and Jelena Pancevac, photographs by Stefano Graziani (Buy from Walther König/DAP / from Amazon / from Bookshop)

I have many vivid memories from the semester I spent in Italy during architecture school in 1995. The experience of visiting buildings designed by Carlo Scarpa, which I touched upon last week, is just one. Another memory, relevant here, happened during a day spent in Urbino, the hill town in the Marche region that is famous as the birthplace of Rafael and, architecturally, for the Ducal Palace, an impressive Renaissance building that helped make the historic center a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Following a morning with an organized visit to the palace and other places in the center, my classmates and I were left to our own devices for the afternoon. I have long been intrigued by the insertion of new buildings in old contexts, so my goal was to visit the curving university building that Giancarlo de Carlo inserted among the town’s old brick buildings:

But, being by myself and not knowing the exact location of the building — Magisterio is its name, I later learned — with the best rudimentary Italian that I could muster from a crash course my classmates and I took the previous semester, I asked a local where to go and was given directions that actually led me outside of town. At one point I considered walking back up the hill to wait by our bus until it departed, but then I saw a sign for the university and soon came across buildings that looked, not like the photo above, but like this:

Turns out I had been pointed toward, not the Magisterio, but the handful of Collegi that de Carlo had designed and realized from the mid-1960s until the early 1980s: residence halls meant to accommodate the thousands of students that would descend upon the small town at various intervals over the course of a year. At the time, as a student more concerned with the whats and hows of things rather than the whys and whens, the buildings in concrete and brick were far from beautiful but were interesting for the way they integrated themselves into the landscape. As opposed to the Magisterio, which is embedded within the urban landscape of the hill town, the sloped site of the Collegi was basically unencumbered of human interventions, elevating the important of the landscape in the architect’s design. De Carlo’s approach was two-fold: following the hillside in some of the buildings and stepping down the slope in others such as the Tridente — pictured here, it was the second of the five Collegi complexes located about one mile southwest of the Ducal Palace.

Although my unplanned discovery of the university buildings on the outskirts of Urbino was fairly unique, I’m far from alone in appreciating the buildings de Carlo designed for the town. One particular architect is Kersten Geers, who took his spring 2023 Everything studio from the Academy of Architecture USI in Mendrisio, Switzerland, to Urbino, documenting the five Collegi but also the Faculty of Law and Magisterio in the center and the Scuola del Libro northwest of the center. The resulting book, edited by Geers with Jelena Pancevac and released earlier this month, contains a few short texts (the main one putting the projects within the context of Team 10, a subject touched upon at the bottom of this newsletter), drawings of the eight projects by the students, and photographs of the same by Stefano Graziani. The last comprises 200 of the book’s 264 pages and number half as much, since each photograph is presented full-bleed across a two-page spread.

One of the notable characteristics of 99 of the 100 photographs is the absence of people (there is one photo with one person in it). Yet, unlike traditional architectural photography that omits people (or turns them into translucent blurs) to put the focus on the architecture and present the building in its best literal and figural light, Graziani’s photographs are nearly the opposite: documentary-like, matter-of-fact, and decidedly unsexy. The reason? De Carlo “built relentlessly with good intentions for a society that believed in a better future,” Geers writes on his firm’s websites, but “what remains is bare architecture, no longer celebrated, nor vilified.” More than a documentation of buildings decades after their realization, the studio approached them as a “testbed for considering the aftermath of modernism.” Given this approach, the empty and almost melancholy photos by Graziani are more than appropriate.

Books Released This Week:

(In the United States, a curated list)

The Architect's Sourcebook: Dimensions and Files for Space Design by Stanislas Chaillou (Buy from Birkhäuser / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — Billed as “an accessible and playful space planning manual for the digital age,” is loaded with drawings but also comes with “1000+ readily downloadable CAD blocks [that] designers actually need to draw spaces in their software.”

Architecture After War: A Reader edited by Bohdan Kryzhanovsky (Buy from MACK / from Amazon) — Co-published by MACK with the Ukranian platform CANactions, this readers presents essays covering reconstruction after WWII and other past wars to theoretically consider what architects, planners, students, and citizens can do for Ukraine once its eventual reconstruction takes place.

Perspecta 56: Not Found edited by Guillermo Acosta Navarrete and Gabriel Gutierrez Huerta (Buy from The MIT Press / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — The latest issue of Perspecta, Yale’s student-run architecture journal, “considers the complexities and potentialities of architectural concealment, obfuscation, and mimicry; of the power inherent in architecture's expanding capacity as media.”

Set Pieces: Architecture for the Performing Arts in Sixteen Fragments by Diamond Schmitt Architects (Buy from Birkhäuser / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — This monograph focusing on one typology designed by one firm “pairs the words of leading artists and critics with details showcasing the design and inner workings from projects by Diamond Schmitt Architects for some of the world’s most remarkable performing-arts buildings.”

Full disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, AbeBooks Affiliate, and Bookshop.org Affiliate, I earn commissions from qualifying purchases made via any relevant links above and below.

Book News:

Domus rounds up ten books — on “aquariums, mushrooms, artificial intelligence, barricades” — for the summer.

Zach Mortice reviews Chacarita Moderna: The Brutalist Necropolis of Buenos Aires by Léa Namer, a case study on the seminal work of Argentine architect Itala Fulvia Villa.

The Met has an eight-minute video with curator Femke Speelberg and book conservator Clare Manias discussing Vitruvius’s Ten Books on Architecture and repairing the museum’s 17th-century copy of the book.

Ian Volner reviews Rat City: Overcrowding and Urban Derangement in the Rodent Universes of John B. Calhoun by Jon Adams and Edmund Ramsden, a story about a man studying rats and the impact his findings had on thinking about cities in the United States in the 1960s.

From the Archives:

This week’s “Book of the Week,” Experiments in Thickness, is far from the first book devoted to Giancarlo de Carlo’s work in Urbino. In 1970, MIT Press published Urbino: The History of a City and Plans for its Development, a translation of a 1966 book in Italian containing his detailed study of Urbino's problems and his masterplan for its evolution. But that book is scarce, fetching hundreds of dollars on AbeBooks, and is not a book I’m familiar with. A more recent title is Spiriti | Eight photographers recount Giancarlo De Carlo in Urbino, published by Corraini Edizioni in 2021 to coincide with the exhibition of the same name at the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche at the Palazzo Ducale in Urbino. I’m not familiar with the later book’s contents either, but the publisher’s descriptions indicates it is primarily a book of photographs that, in a different approach to Experiments in Thickness, actually includes the people who inhabit(ed) the buildings. Still, there are two older books in my library that include Giancarlo de Carlo’s work in Urbino alongside other contents.

In the fall of 1966, Giancarlo de Carlo organized a meeting of Team 10, the successor group to CIAM (Congrès Internationaux d'Architecture Moderne), in Urbino, coinciding with the completion of the Collegio del Colle, the first of the residence halls he designed for a sloped site southwest of the town’s historic center. The event clearly indicates that De Carlo had an important role within Team 10 and that the project aligned with the group’s beliefs — or at least the beliefs of some of the architects in the group, according to this Dutch website devoted to Team 10, since division within the members seems to have been a constant from when the group came together in the mid-1950s until it dissolved in 1981.

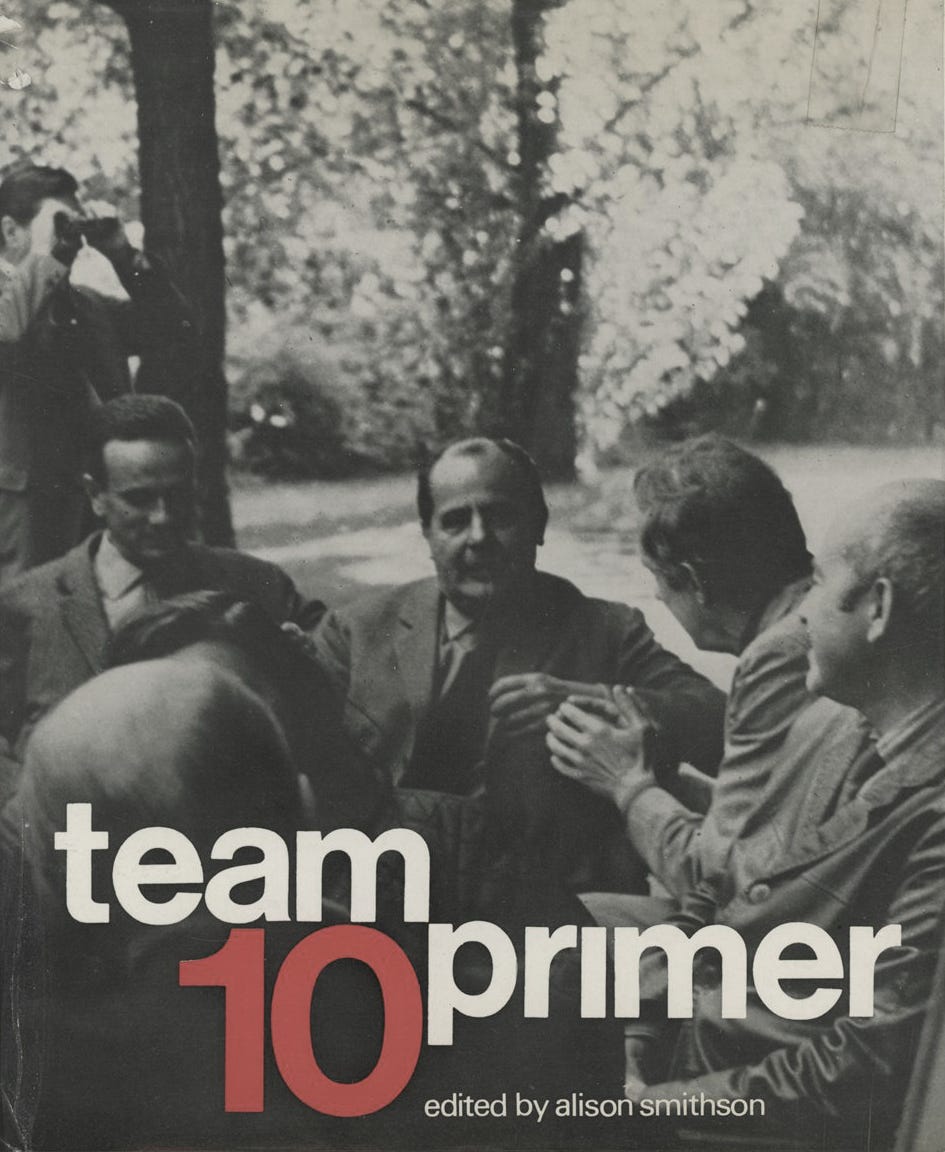

Alison and Peter Smithson were two of the most outgoing voices in Team 10, so suitably Alison edited Team 10 Primer, first published in 1962 and then republished in edited form by the MIT Press in 1968 (hardcover) and 1974 (paperback). The book could be considered a manifesto of the group’s various positions and is structured a bit like a reader: a collage of essays, snippets, projects, and other output by the members of Team 10 — one of them de Carlo, whose project in Urbino occasionally appears in its pages. The book was intended for students and to capture the positions of Team 10’s members, and the latter dictated the thematic chapters but also, unfortunately, an overly busy and complex page design with five types of content (“carrying text,” supplemental text, “verbal illustrations,” footnotes, captions) that make any attempt to read it cumbersome and frustrating. While it is important as a historical document, I can only otherwise recommend it to architects who appreciate the work of Team 10 members, especially the Smithsons.

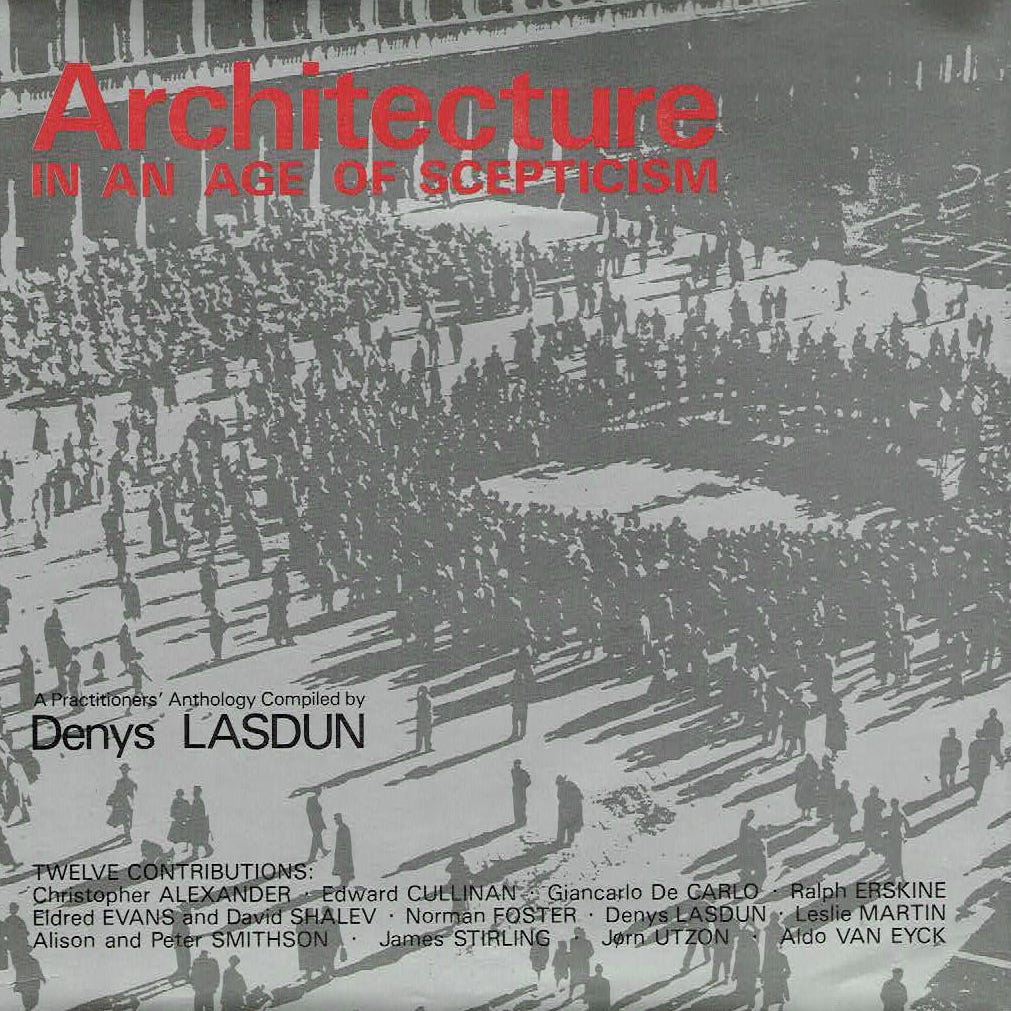

A lesser-known book than Team 10 Primer, but one that I can endorse heartily, is Architecture in an Age of Skepticism: A Practitioners' Anthology, which was compiled by British architect Denys Lasdun (1914–2001) and published by Oxford University Press in 1984. It features twelve contributions by thirteen architects presenting one or more of their projects in depth. Giancarlo de Carlo is one of them and “The University Centre, Urbino” is the project. De Carlo describes the genesis and aims of the project, the complexities of building in Urbino, and the designs of the student residences outside the center of town. The words, drawings, and photographs — the last are, like the rest of the book, in black and white, more in line with traditional architectural photography than Graziani's photos in Experiments in Thickness — serve to give readers a thorough understanding of the whats, whys, and hows of de Carlo’s project. The same can be said of the other contributors, some of which overlap with de Carlo, as in Team 10’s Aldo Van Eyck and Alison and Peter Smithson; others include Christopher Alexander, Ralph Erskine, Norman Foster, Lasdun himself, James Stirling, and Jørn Utzon. “Each contribution gains clarity and power from the company of its fellows,” Lasdun writes in the preface. This assertion is aided by Lasdun’s selection: architects who “have a similar seriousness in their approach to architecture, a similar desire to express the fundamentals of their art and to advance it in relation to people and society.” The book may be of its time — “an age of skepticism” — but I could see books made in the same vein today being just as relevant.

Thank you for subscribing to A Weekly Dose of Architecture Books. If you have any comments or questions, or if you have your own book that you want to see in this newsletter, please respond to this email, or comment below if you’re reading this online. All content is freely available, but paid subscriptions that enable this newsletter to continue are welcome — thank you!

— John Hill