This newsletter for the week of July 29 takes a look at the new monograph on ODA, the New York firm headed by architect Eran Chen. The new book comes six years after the first monograph on ODA, which is featured in the archive at bottom. In between are the usual new book releases and headlines. Happy reading!

Book of the Week:

ODA: Office of Design and Architecture by Eran Chen (Buy from Rizzoli / from Amazon / from Bookshop)

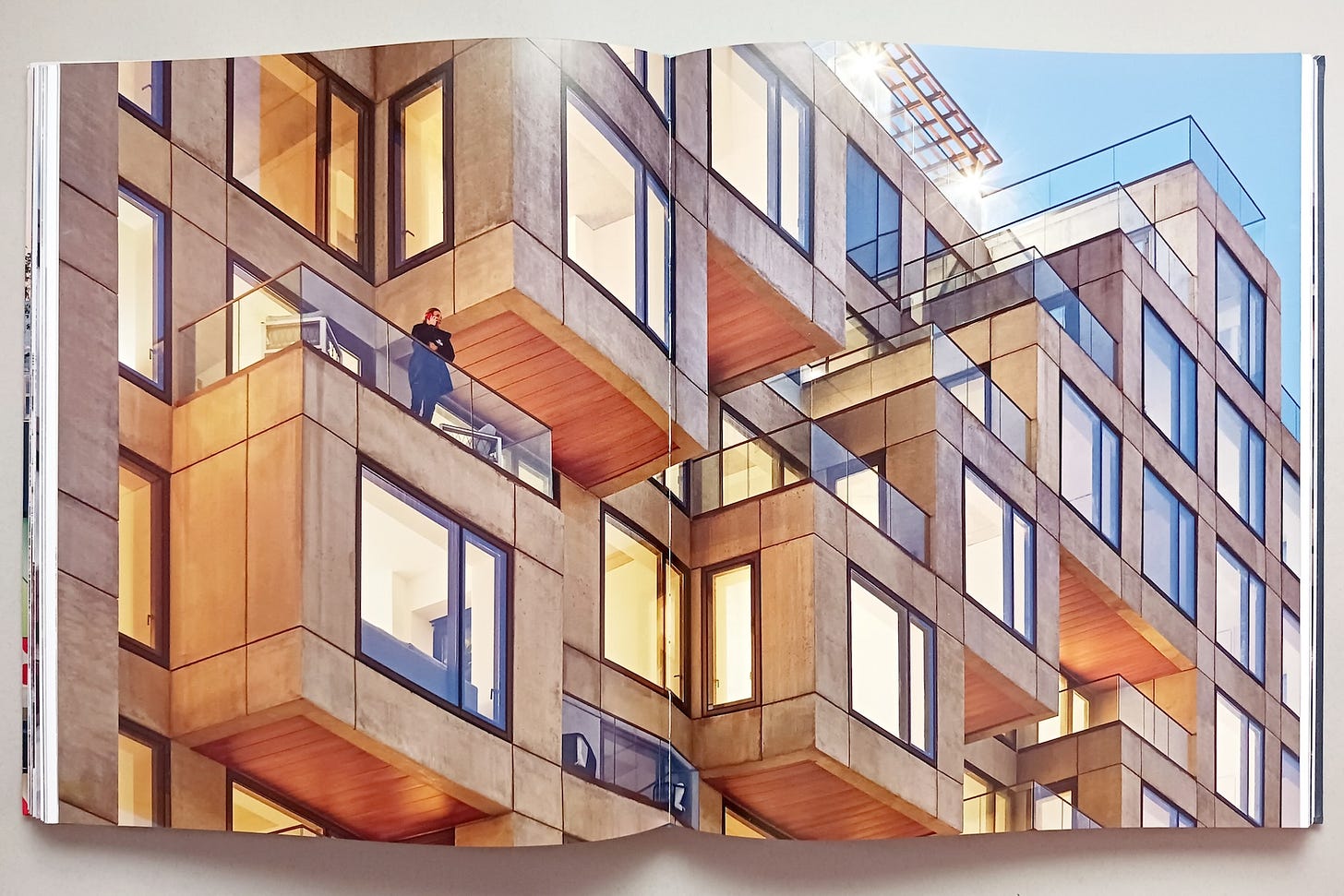

Ever since architect Eran Chen left Perkins Eastman to form ODA around 2007, his primarily residential projects in New York City have stood out for a few defining formal characteristics: generous terraces and balconies, stepped facades, and asymmetrical rooflines. My first exposure to ODA was 15 Union Square West, the adaptive reuse and vertical expansion of a five-story cast-iron building that Charles Lewis Tiffany built overlooking Union Square Park in 1870. At night one can see the old arched windows behind the new curtain wall, while during the day the apartment building, with its cantilevers and shifted floor plates defining its seven additional floors, looks wholly new. Subsequent ODA buildings tended to be new construction rather than commercial-to-residential conversions, meaning that in some cases the stepping and terracing that was limited to the top half at 15 USW could cover nearly the whole building, as in 2222 Jackson in Queens and 98 Front in Brooklyn, as seen in this spread from ODA: Office of Design and Architecture:

One could look at these and other ODA apartment buildings as ways of reinvigorating New York City streetscapes; of bringing the lives of the urban dwellers to the street, to the large outdoor spaces extending from the apartments. Many older and contemporary apartment buildings in the city have balconies (fewer have terraces), but they tend to be shallow and barely usable for more than one person so sit and/or smoke. As an alternative, Chen and ODA have been able to convince the developers they work with to create substantially larger, room-size balconies and terraces, melding them with cantilevered volumes to enliven the facades and give the impression that the city is a playground that reaches from the streets to the rooftops — one could imagine a giant seeing it that way, at least.

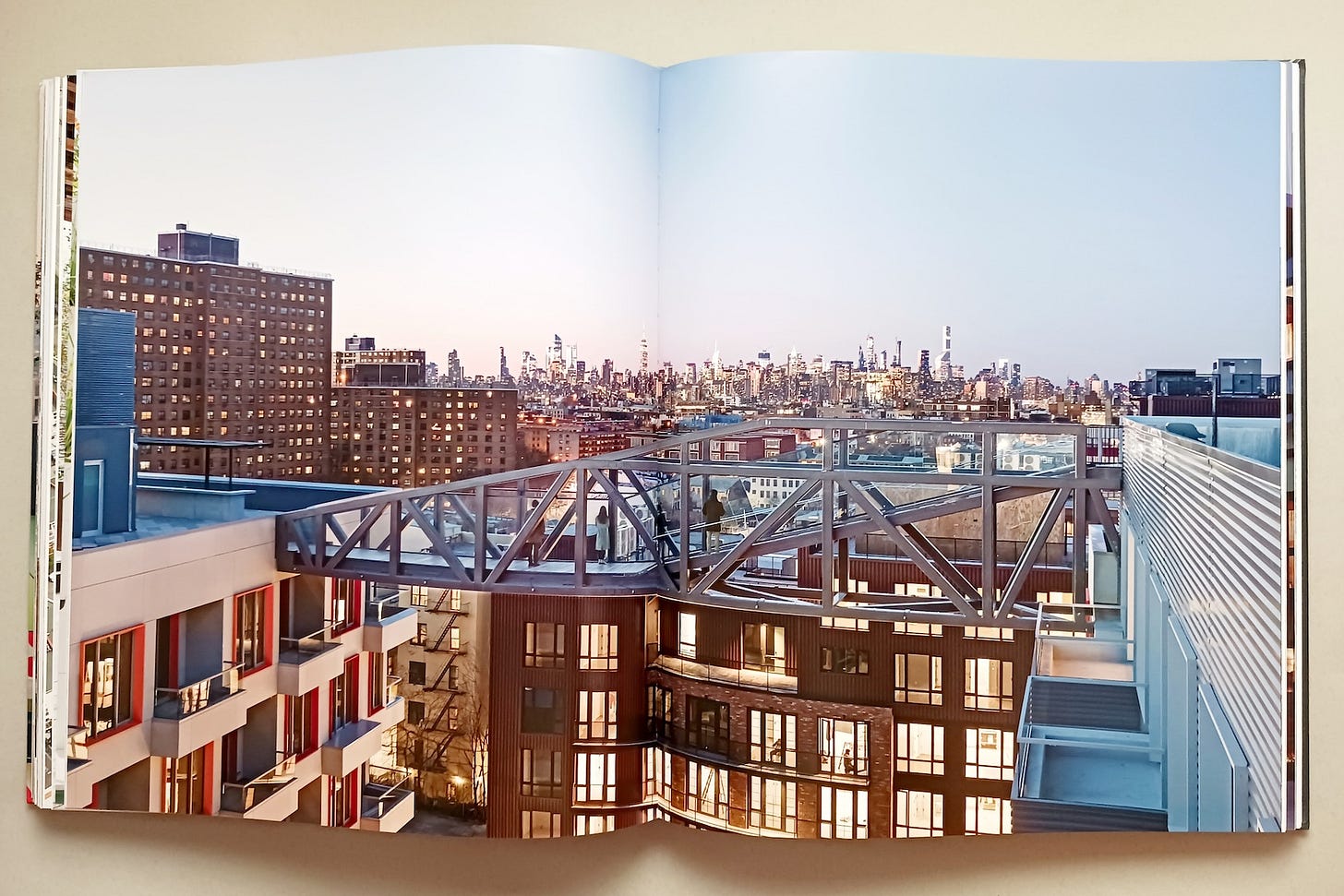

No wonder that Chen, in his introduction to the eponymous coffee table book published in March by Rizzoli, offers yet another twist on “form follows function,” Louis Sullivan’s phrase entrenched in every architect’s head: “Form Follows Function” [sic], or “Form Follows Fun.” And no wonder ODA has been able to speedily move from projects like 15 USW, with 36 apartments over 12 floors, to larger “playgrounds” for urban residents, such as the one-million-square-foot, two-block Denizen, which graces the cover of the book, and the nearby 10 Montieth (aka The Rheingold, after the brewery that once occupied the site), which is topped by a huge sloping rooftop garden linked by steps and a bridge:

Fittingly, given ODA’s growth over the last decade and a half, the monograph is organized into four chapters that increase in size from small to extra-large: Apartment, Building, Block, Neighborhood. This format means the book basically works in chronological order, with earlier projects such as 2222 Jackson and 98 Front in the Building chapter, and Denizen, Rheingold, and later projects in the Block chapter. The Neighborhood chapter is exclusively made up of renderings for future projects, most of them outside of New York City and all of them showing architectural solutions that depart from ODA’s signature stepped terraces and asymmetrical rooflines.

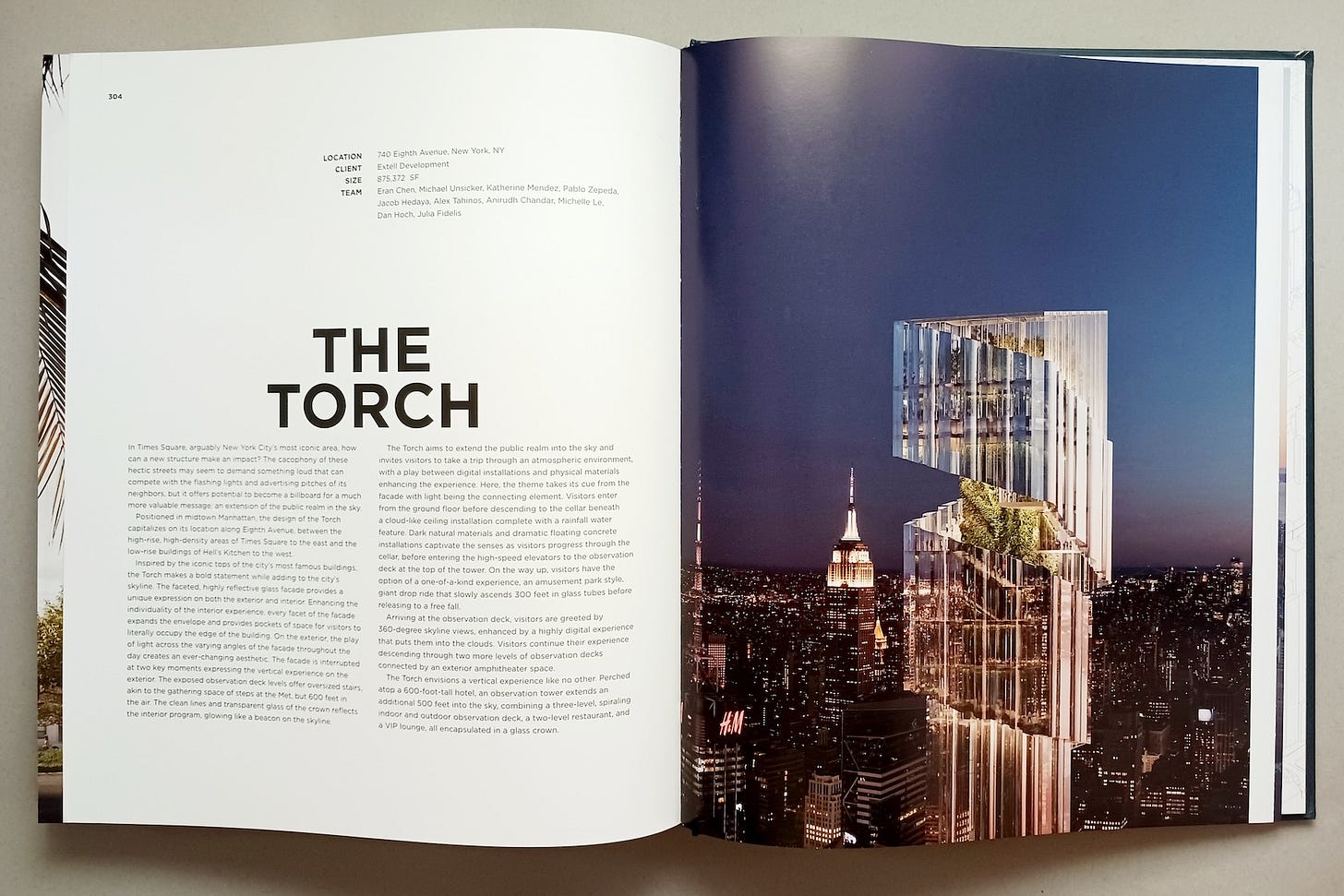

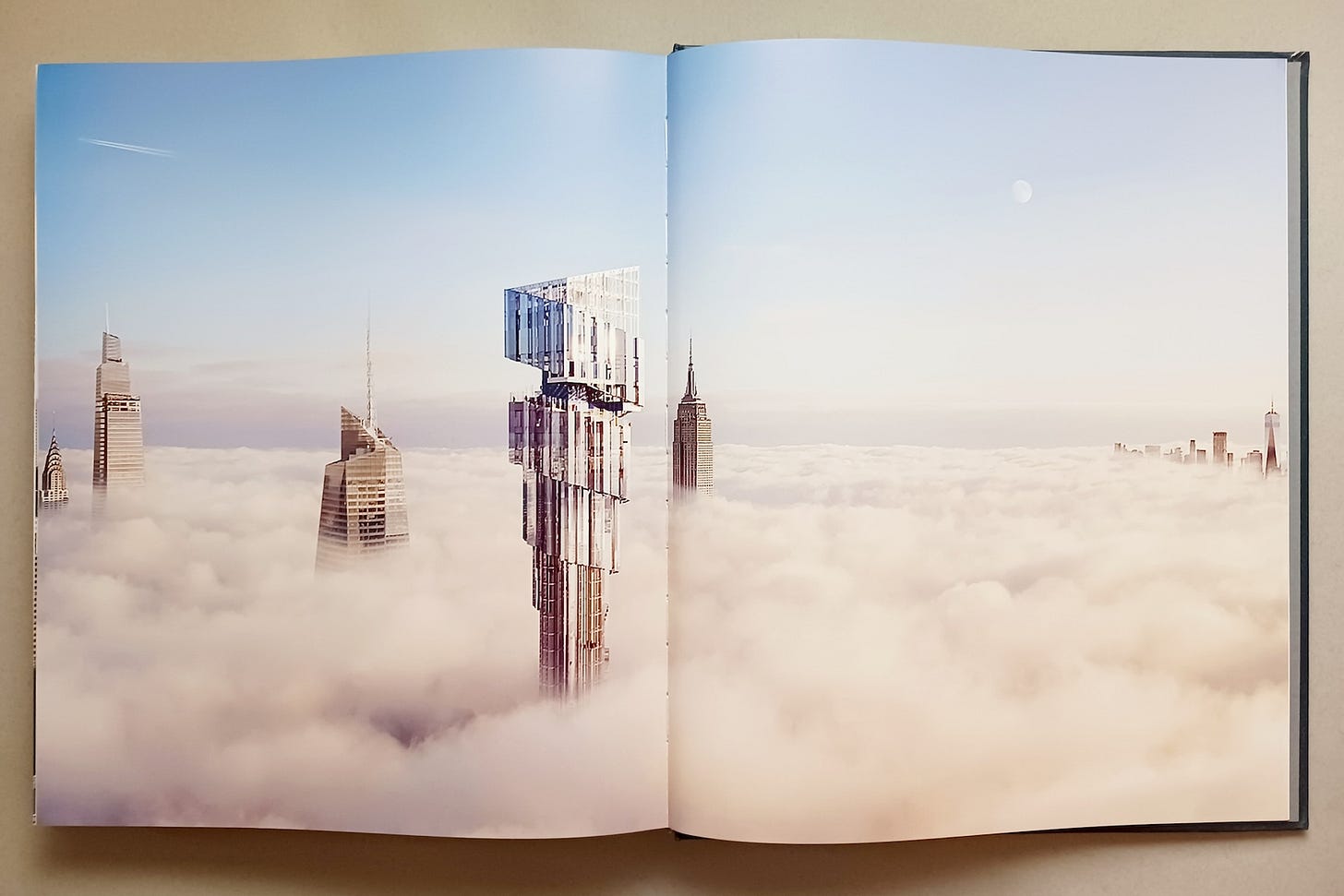

Still, one NYC project in the last chapter stands out for its audacity and, frankly, for its oddness: The Torch. Planned for a site at Eighth Avenue and West 46th Street on the edge of Times Square, the supertall skyscraper will have an observation deck, restaurant and lounge, and thrill ride, all 500 feet above a 600-foot-tall hotel. Programmatically, this makes sense for Times Square, but architecturally it is off-putting, at least at first glance: top-heavy and only bearing a slight, if questionable resemblance to the namesake torch of the Statue of Liberty. Although renderings were revealed by New York YIMBY in March and construction appears to have started on the project, the Torch is nowhere to be found on ODA’s website nor can be it found in the New York Times or any other news outlets via Google.

Yet, what did make its way into the Times earlier this month was “High Above New York, a Battle for Tourist Dollars,” a multimedia piece about the rooftop “experiences” at Rockefeller Center, One Vanderbilt, 30 Hudson Yards, and the Empire State Building. The experiences range from tame (wake up early and have a Starbucks while you watch the sunrise from the top of ESB) to stomach-churning (leaning back over the edge of a skyscraper at Hudson Yards while donning a harness), but all of them are expensive and point to the need for ever more creative gimmicks to attract those tourist dollars. With an “amusement park style, giant drop ride” at its apex, the Torch is the apparent zenith of this trend — unless something even more audacious comes along in the months and years it takes to complete it. Curiously, or maybe tellingly, the Torch is not mentioned in the Times article as a similar experience that is in the pipeline.

While the Torch fits in snugly with this century’s convergence of the experience economy and supertall skyscrapers, I’m still bothered by that top-heavy form; I also don’t see time and a jump from rendering to reality helping matters. But Eran Chen’s reworking of Sullivan’s phrase to Form Follows Function is telling, especially given that the word “function” is changed to “fun” via a strikethrough of the remaining letters. This says to me that function is still there, it is still important, but it is in the service of fun, however one defines that. Fun at the Torch would be many things for many types of people: eating and drinking at 1100 feet (yes, please); walking exterior stairs at the same height (sure, I’ll get in my steps); or dropping 300 feet in a free fall (a hard pass). All of these things together — their functions — point to a top-heavy crown (or torch) and, below it, a slender shaft with space for the free fall. The result then is dictated by its function, one that happens to be all about fun, and which sees the city more as a playground than as a place to live, learn, and work.

Books Released This Week:

(In the United States, a curated list)

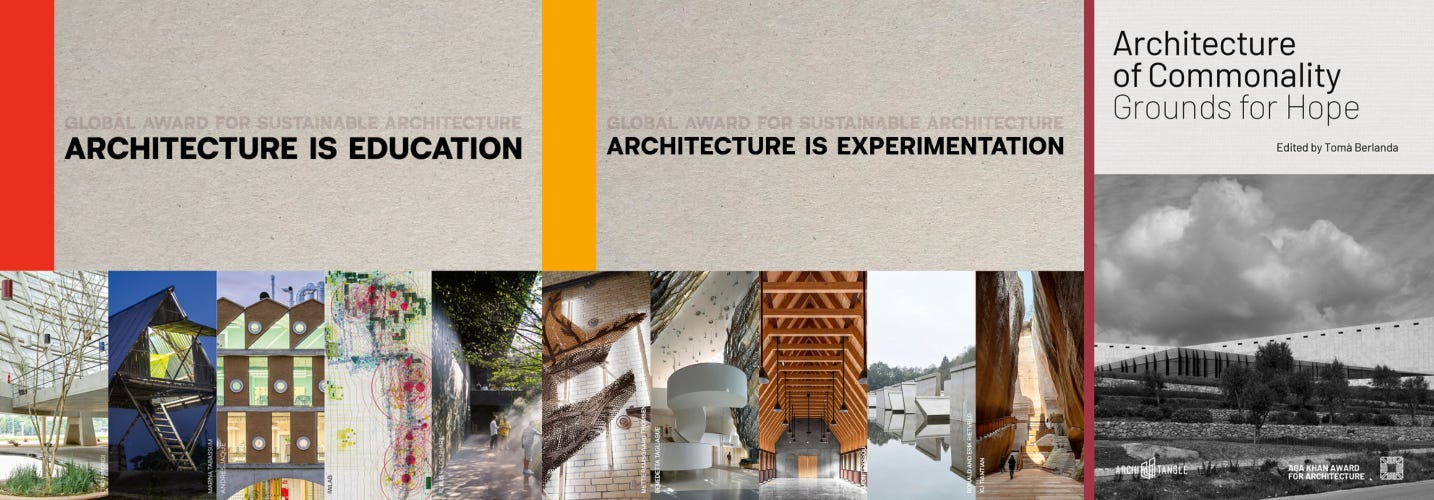

A trio of titles from ArchiTangle which were previously announced in Week 22/2024 but are actually being released this week:

Architecture Is Education: Global Award for Sustainable Architecture and Architecture Is Experimentation: Global Award for Sustainable Architecture, both edited by Jana Revedin & Marie-Hélène Contal and published by ArchiTangle (Buy Education from ArchiTangle / Amazon / Bookshop; Buy Experimentation from ArchiTangle / Amazon / Bookshop) — A pair of books on The Global Award for Sustainable Architecture, which was created in 2006 and is under the patronage of UNESCO, respectively about “how architectural education is a vital force in addressing global sustainability challenges” and “how architectural practice can lead to significant social, economic, and environmental progress.”

Architecture of Commonality: Grounds for Hope edited by Tomà Berlanda, published by ArchiTangle (Buy from ArchiTangle / Amazon / Bookshop) — Documentation of the Palestinian Museum in Birzeit, West Bank, one of the winners of the 2019 Aga Khan Award for Architecture, accompanied by essays on the role of museums and cultural institutions in Palestine and the Arab world. The book follows the format of Hutong Metabolism: ZAO/standardarchitecture, the 2021 book celebrating a winner of the 2016 Aga Khan Award for Architecture.

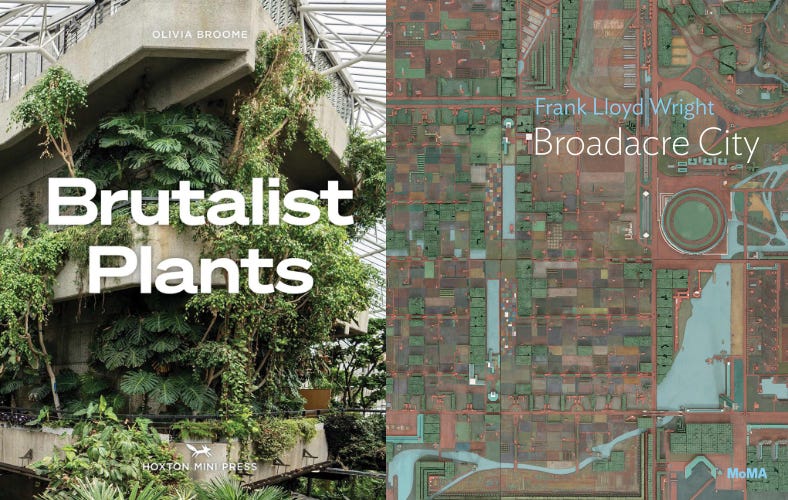

Brutalist Plants by Olivia Broome (Buy from Hoxton Mini Press / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — The latest book to hop on the brutalist bandwagon looks at the contrast between the natural and the manufactured, between plants and concrete; from the creator of the Brutalist Plants Instagram account.

Frank Lloyd Wright: Broadacre City by Juliet Kinchin (Buy from MoMA / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — This slim, Pamphlet Architecture-sized volume in the MoMA One on One Series focuses on Wright’s Broadacre City and the colossal relief model that Wright and his apprentices built in the mid-1930s — a highlight of MoMA’s architecture collection.

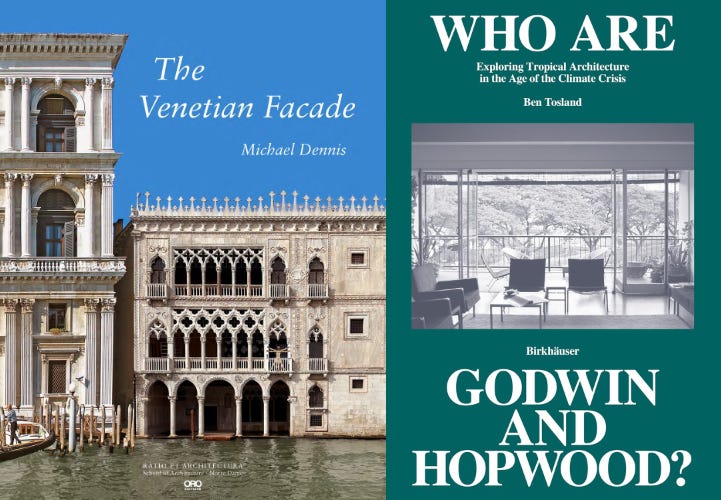

The Venetian Facade by Michael Dennis (Buy from ORO Editions / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — This book “explores the art and typology of the Venetian facade, not only as a high point of architectural literacy and achievement, but as a potentially useful contemporary stimulant.”

Who Are Godwin and Hopwood?: Exploring Tropical Architecture in the Age the Climate Crisis by Ben Tosland (Buy from Birkhäuser / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — The first comprehensive monograph on John Godwin and Gillian Hopwood, both of whom studied at the Architectural Association in London and then moved to Nigeria, “where they significantly shaped the country's architectural landscape for more than sixty years.”

Full disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, AbeBooks Affiliate, and Bookshop.org Affiliate, I earn commissions from qualifying purchases made via any relevant links above and below.

Book News:

Australian architecture critic Elizabeth Farrelly starts her recent piece, “The oxymoron of American architecture,” by recounting how she "recently de-acquisitioned — sold, gave away or dumped — almost all [her] books on American architecture." (Well, this makes me feel alright about de-acquisitioning Farrelly’s Blubberland.)

Over at Building Design, Niklaus Graber reviews a new guide to the architecture of Bangladesh’s booming capital city: Architecture Guide Dhaka, written by Sayed Ahmed and published by DOM.

The Seaside Institute has bestowed its 2025 Seaside Prize on architects and academics Ellen Dunham-Jones and June Williamson, co-authors of the “groundbreaking” Retrofitting Suburbia series of books.

Read an interview with (retired) architecture book proprietor William Stout at Kazam!, the magazine of the Eames Institute, the new owner of the bookstore. (I’m guessing the interview was published around the time of the late-2022 handover, though it’s undated and I just discovered it.)

From the Archives:

Rizzoli’s ODA: Office of Design and Architecture is not the first ODA monograph. Back in 2019 I reviewed their first, Unboxing New York (Actar, 2018), on my blog, writing: “ODA New York takes a dramatically different approach [than traditional architecture monographs] with Unboxing New York, creating something that is more akin to a textbook than a monograph. […] As hinted on the cover, Unboxing New York is made up of five chapters: Living, Zoning, Developing, Marketing, and Building. These correspond roughly with the process of architecture and specifically to residential projects in NYC: Living outlines the theoretical basis for ODA's designs; Zoning shows how ODA uses codes to their advantage and those of their clients; Developing lays out how developers approach residential projects; Marketing deals with communication and “selling” designs to the public; and Building hones in on ODA's own practice and some details of construction. […] The combination of bite-sized essays, hundreds of descriptive diagrams, and unabashed embrace of residential development makes Unboxing New York an insightful, educational look at the inner workings of ODA as well as the city it calls home.”

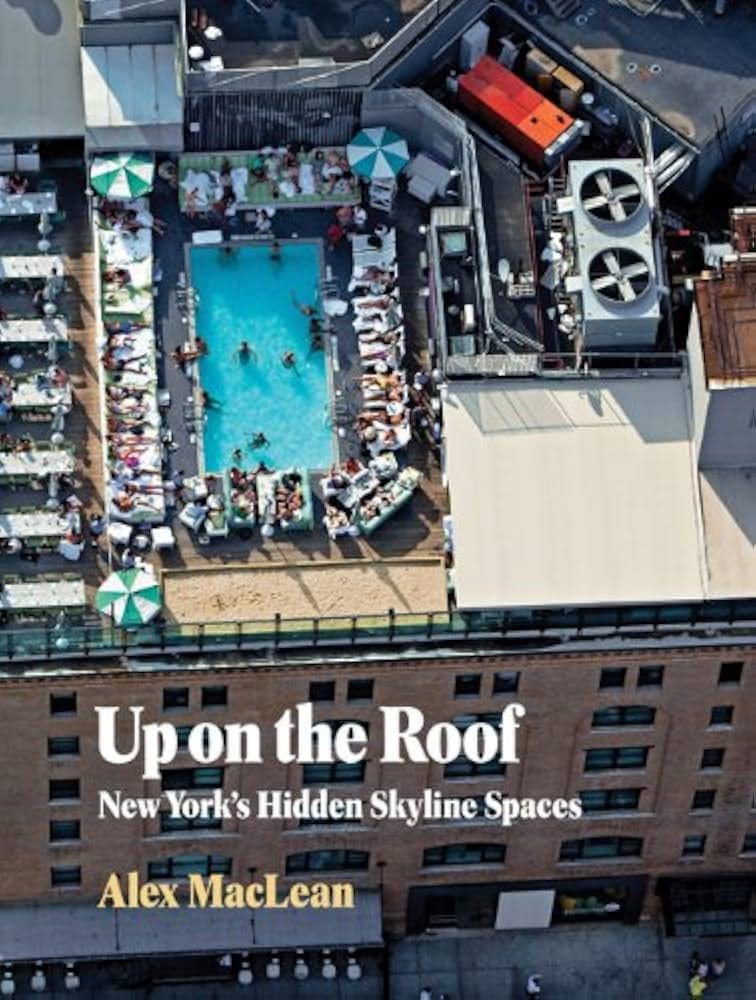

A good decade before the various above-mentioned experiences were added to the tops of old skyscrapers and newcomers on the scene, Princeton Architectural Press put out Alex MacLean’s Up on the Roof: New York’s Hidden Skyline Spaces. Released in 2012, the book of MacLean’s aerial photographs reveals the rooftops that are alternatively home to mechanical equipment, gardens, solar panels, swimming pools, terraces, and observation decks. The cover photo is telling: sunbathers crowd the pool at Soho House in the Meatpacking District, unaware of the large air handler and other mechanical equipment one floor above them. The same is true of people across the city — outside of those living in high rises, that is — who can only imagine what is transpiring on the rooftops high above their heads. MacLean’s lens reveals that much of what is hidden on rooftops is exceptional, but just as much of it is mundane. And for every packed-to-the-gills swimming pool there are ten roof terraces full of furniture but free of occupants, or dozens of flat roofs without any provisions for occupation. Put simply, the book reveals the potential of urban rooftops, both actual and imagined, by revealing the hidden. Google Maps does the same, but not as beautifully as MacLean.

Thank you for subscribing to A Weekly Dose of Architecture Books. If you have any comments or questions, or if you have your own book that you want to see in this newsletter, please respond to this email, or comment below if you’re reading this online. All content is freely available, but paid subscriptions that enable this newsletter to continue are welcome — thank you!

— John Hill