This newsletter for the week of September 23 reviews Vishaan Chakrabarti’s new book, The Architecture of Urbanity, lists ten books being released this week, links to a few headlines, and digs a couple books related to the “Book of the Week” from the archive. Happy reading!

Book of the Week:

The Architecture of Urbanity: Designing for Nature, Culture, and Joy by Vishaan Chakrabarti (Buy from Princeton University Press / from Amazon / from Bookshop)

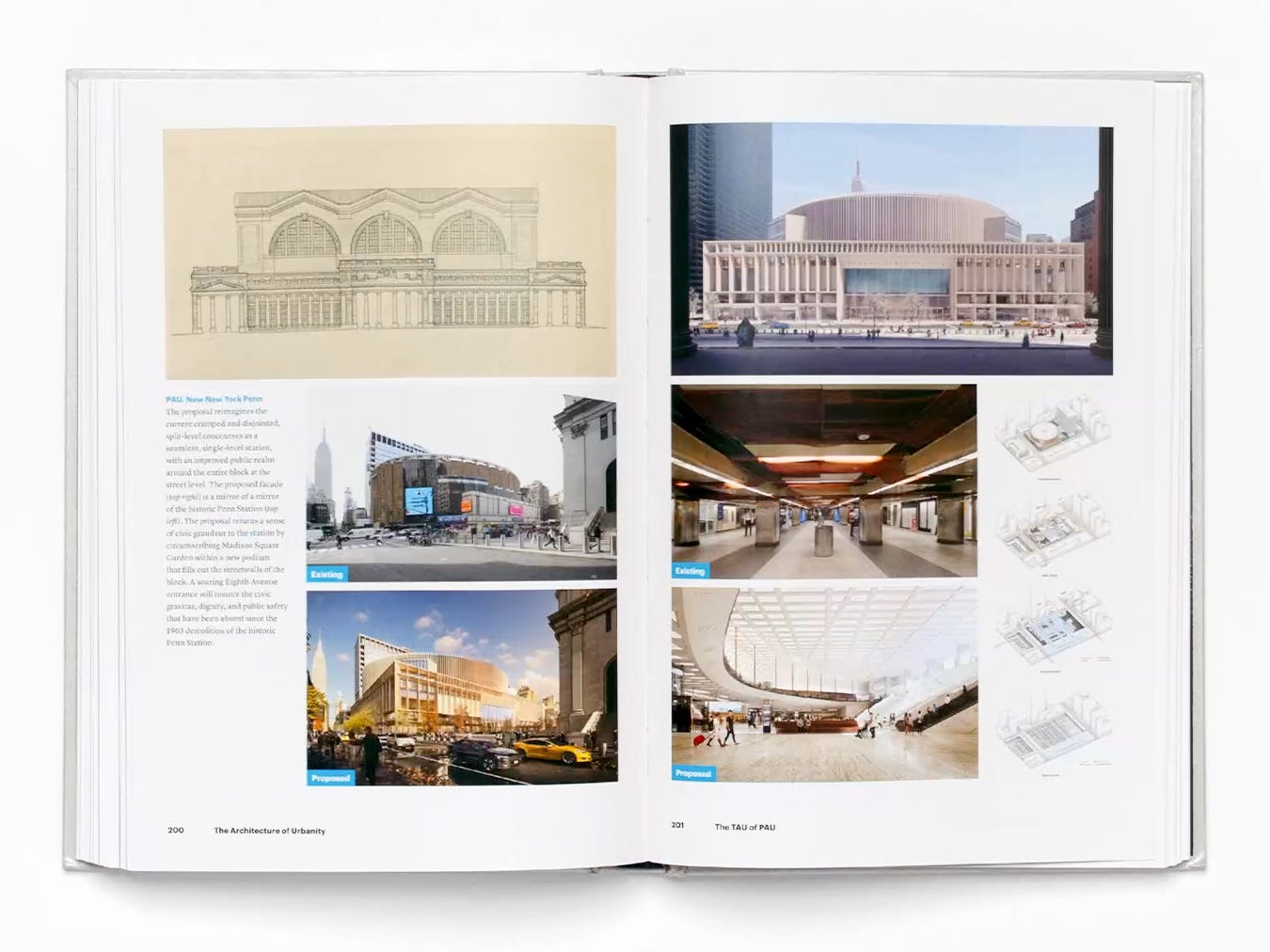

Released this week, The Architecture of Urbanity is the second book by PAU | Practice for Architecture and Urbanism founder Vishaan Chakrabarti, coming eleven years after his first book, A Country of Cities: A Manifesto for an Urban America, published in 2013 by Metropolis Books. Even though Chakrabarti contends The Architecture of Urbanity is his second book, it is actually his third. In the same year as A Country of Cities, Columbia Books on Architecture and the City published NYC 2040: Housing the Next One Million New Yorkers, co-authored by Chakrabarti and Jesse M. Keenan, both of whom were in Columbia GSAPP’s Center for Urban Real Estate (CURE), which had proposed the far-fetched idea for bridging Lower Manhattan and Governors Island to create LoLo, or Lower Lower Manhattan, in 2011.

At the time of A Country of Cities and NYC 2040, Chakrabarti was also a partner at SHoP Architects, a position he held for about three years, leaving to form PAU in 2015. Since then his firm has won numerous competitions and gained other commissions, he briefly served as dean of UC Berkeley’s College of Environmental Design, he has given a trio of TED Talks, and he has introduced ideas on urban planning to a wider public via the New York Times. Even leaving out his pre-SHoP and -GSAPP experience (which included SOM, NYC Planning, and Related Companies), it goes without saying that Chakrabarti’s CV makes him one of the leading experts on and champions of urbanism today and one of the most likely people to write a book about “Designing for Nature, Culture, and Joy” in American cities and suburbs.

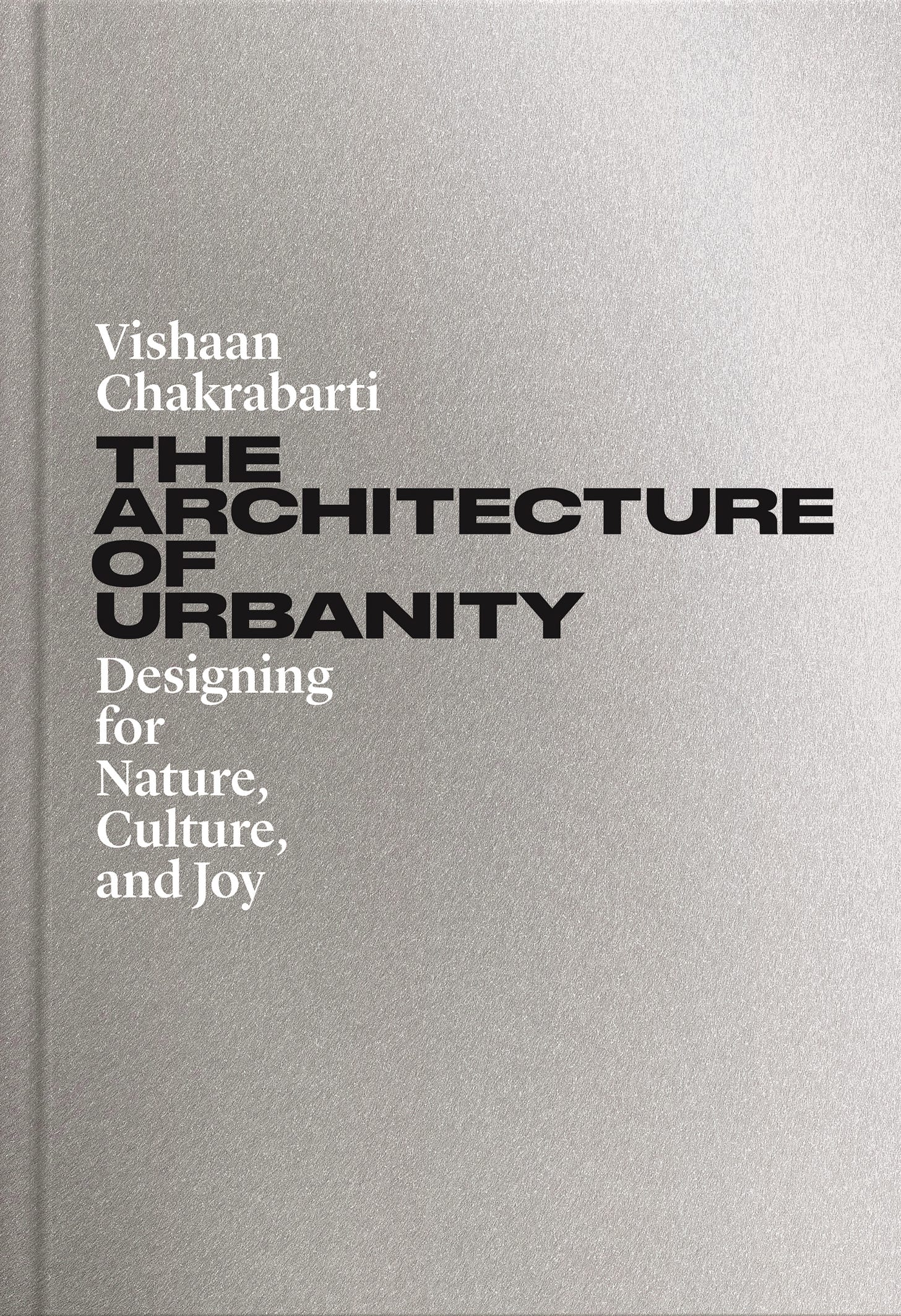

The subtitle of The Architecture of Urbanity exudes optimism, and ultimately the book is just that, optimistic. But before getting to the “Hope” that makes up the second half of the book, readers have to wade through “Despair.” With wars in Ukraine, Gaza, Sudan, and elsewhere; with right-wing politicians gaining power around the world; with the pandemic just barely in the rearview mirror; and with climate change-induced natural disasters happening at an increased rate, it seems that crises and the concomitant feeling of despair are the new normal. For Chakrabarti, today’s despair is the product of decades of misguided choices, bad planning, exploitation, and other myopic behaviors. The below spread, from one of the three chapters that function as “graphic palette cleansers” between chapters exploring his positions in words, clearly illustrates the disastrous effects the embrace of the automobile has had on cities. (That said, I would have rather seen two images of the same city at the same scale, akin to what I recently shared to Instagram, rather than a US city ripped apart by highways compared to a fully intact European city, a fairly tired argument in urban planning circles.)

Cars are not the only culprit in our present despair, since buildings contribute slightly more carbon to the atmosphere than transportation. But the point to Chakrabarti is that the shape of our cities — the way we move about them and the buildings that comprise them — is of utmost importance and therefore is a source for solutions. The hard part comes in addressing social issues, which modernism tried to do decades ago but failed at. Over the last century or so, the pendulum has swung back and forth between architecture’s ability and inability to have an impact on social issues. We seem to find ourselves today with skepticism over architecture’s role in improving society, tempered by the need for architects to consider social diversity and equity when designing buildings and landscapes. Simply put, architecture is not alone when it is involved in making must-needed social change today: it accompanies political, economic, cultural, and other initiatives aimed at addressing the needs of large and diverse groups of people and allowing them to live fulfilling lives.

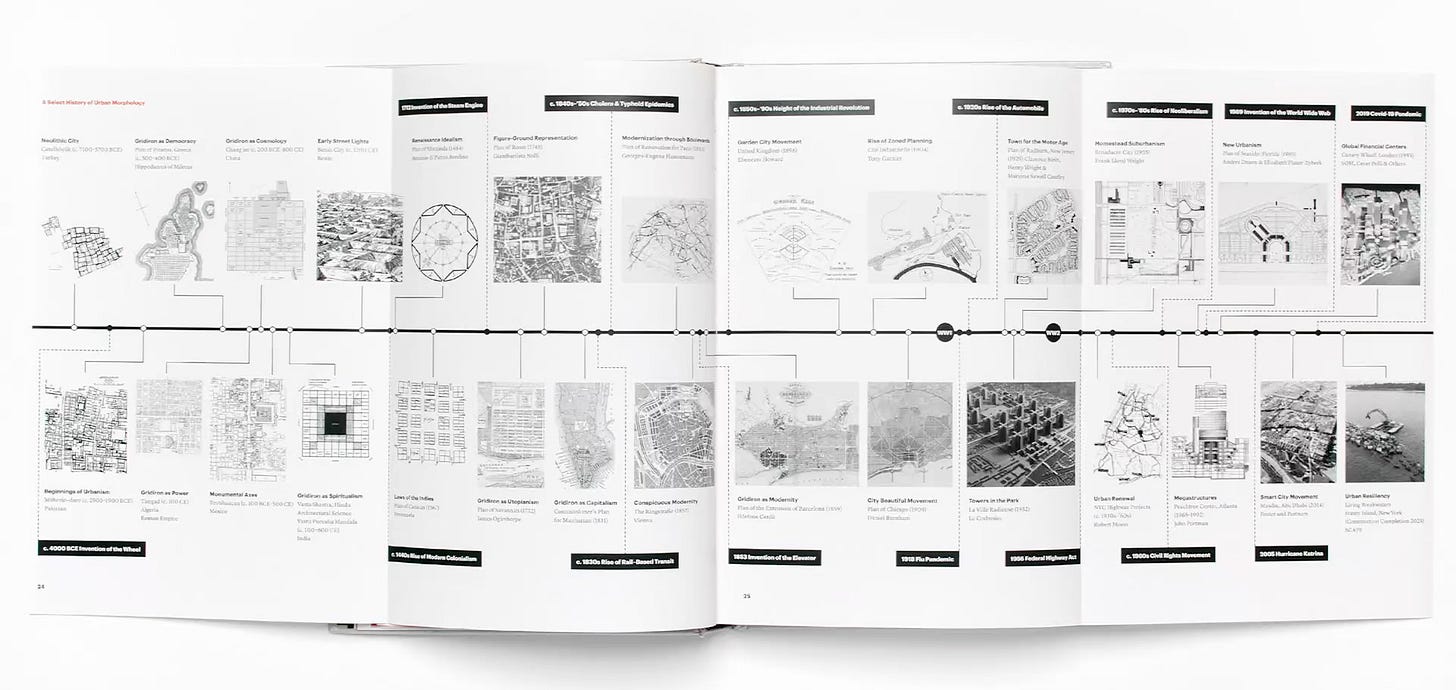

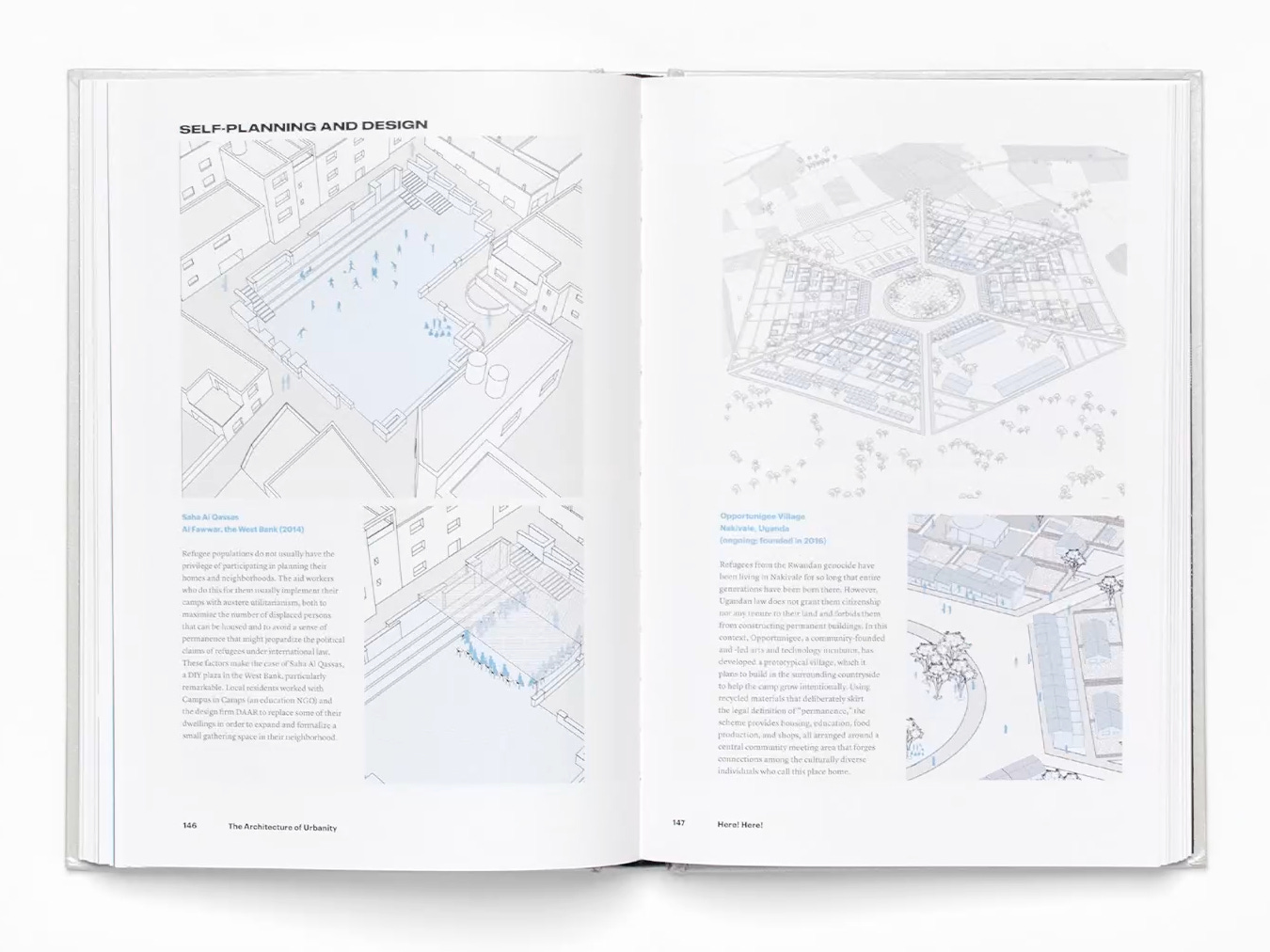

Enter Hope. If the first half of the book, Despair, lays out the problems of the world in the 21st century, the second half, Hope, offers solutions. Not all of them come from PAU, which makes The Architecture of Urbanity more of a manifesto than a monograph, much like A Country of Cities, which is discussed at the bottom of this newsletter. The five chapters that comprise Hope pull successful examples of urbanity — Chakrabarti defines urbanity as “communities that embrace and celebrate pluralism across race, class, and gender” — that span centuries and are being designed today by his contemporaries. One of the goals is to create buildings and public spaces that foster “social friction,” spaces where diverse groups of people can interact; they are the opposite of homogenous enclaves but far from places of fear or violence that might spring to mind when hearing that phrase. “Connective design” is his methodology for “[forging] deeper physical bonds across society at every scale,” something he finds in the work of Lacaton & Vassal, Francis Kéré, Michael Maltzan, and Alejandro Aravena, among others.

The book ends with a proposal for a housing prototype, one that echoes the 2013 book, NYC 2040: Housing the Next One Million New Yorkers, and his 2023 Times op-ed, “How to Make Room for One Million New Yorkers.” But instead of focusing on the five boroughs, Chakrabarti and PAU propose housing that is appropriate to US cities as well as their suburbs, enabling them to sustainably house the millions of people in need of homes now and in the coming decades. The problem arises from today’s housing demands and population growth, and the solution comes in the form of new low-rise construction, which is favored over tall buildings and adaptive reuse due to their lack of sustainability and their lethargy compared to demand, respectively. It is an intriguing idea, but like the myriad proposals to address housing shortages via replicable designs, it needs political and economic support to be more than just words and images in the last chapter of a book.

I started this review of The Architecture of Urbanity with some background on its author because one thing that jumped out to me as I read the book was how much information is omitted from the book. Chakrabarti writes in the first person, is highly opinionated, and occasionally makes revealing statements drawn from personal circumstances, but he omits as much as he includes. While I do not know if Chakrabarti’s split from SHoP was acrimonious, that firm is nowhere to be found in the book, not even in regard to the Domino Sugar Refinery, which PAU designed and is part of a development master planned by SHoP — a masterplan that was carried out when Chakrabarti was partner there. Although the building, a glass box inserted in a landmark brick factory building, is discussed in the seventh chapter*, “The TAU of PAU,” which aligns the studio’s work with the themes of the book, the omission of SHoP made me take note.

Ditto Chakrabarti’s “act of full disclosure,” in regard to skyscrapers, that he is on the board of a start-up whose advances in concrete could make tall buildings more sustainable (something I was not aware of), because he fails to mention that PAU is working with Foster + Partners on 270 Park Avenue, the 60-story skyscraper for Chase Bank that involved the demolition of a 52-story building with LEED Platinum interiors and whose sustainability assertions are dubious. One can read the book feeling that Chakrabarti is forthright, which I think he is most of the time, but for people who know about the things he leaves out, it can also seem he is calculating. So, even when Chakrabarti clearly and logically spells out the pro-growth arguments for his sensible and commendable housing prototype in the last chapter, I can’t shake the feeling that, well, something is missing.

*In the book’s front matter, and here and there in its pages, Chakrabarti refers to the book’s ten chapters by number. But the chapters are not numbered — not in the table of contents nor in the chapters themselves; only in the notes in the back matter. This is mildly frustrating because it requires some unnecessary basic math on the part of the reader, but more importantly it illustrates a disconnect between the author, the copy editor/proofreader, and the book’s designer.

Books Released This Week:

(In the United States, a curated list)

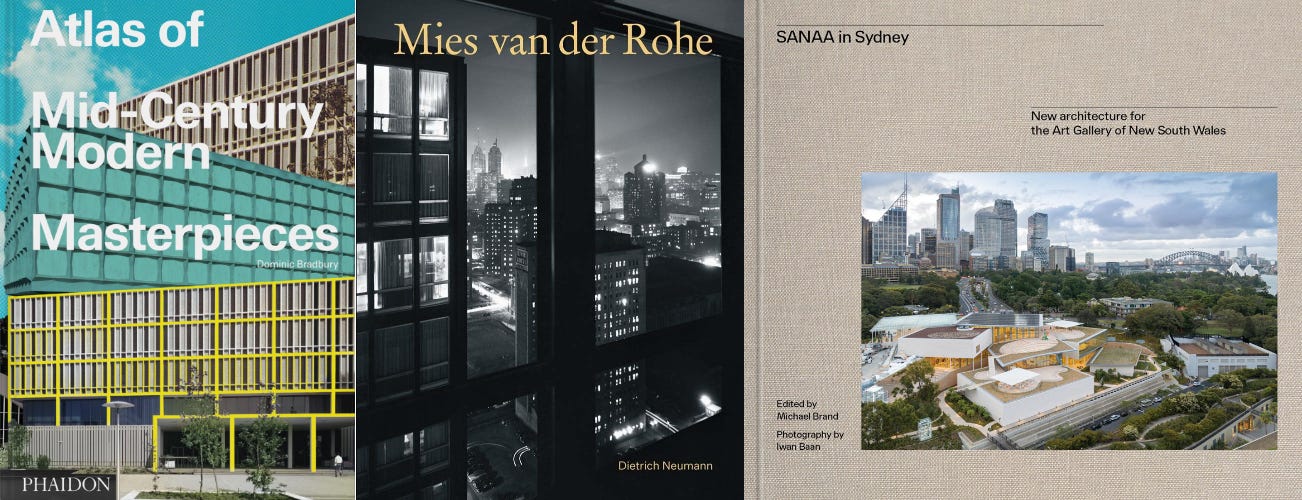

Atlas of Mid-Century Modern Masterpieces by Dominic Bradbury (Buy from Phaidon / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — The publisher of two compact guides to mid-century modern architecture in the United States goes global, putting together a hefty atlas with “450 of the very best works of Mid-Century Modern architecture from every continent.”

Mies van der Rohe: An Architect in His Time by Dietrich Neumann (Buy from Yale University Press / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — The latest book by architectural historian Dietrich Neumann, who has authored and edited numerous books on Mies, “presents a new, critical look at Mies [that] complicates the established narrative about him.”

SANAA in Sydney: The Architecture for the Art Gallery of New South Wales edited by Michael Brand (Buy from University of Washington Press [US distributor for Art Gallery of New South Wales] / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — In 2015 SANAA won the Sydney Modern Project, a competition for the expansion of the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Photographs by Iwan Baan highlight this book documenting the project, which opened to the public in late 2022.

Three new books this week were written by that ultra-prolific author of architecture books, Philip Jodidio:

Calatrava. Complete Works 1979–Today by Philip Jodidio (Buy from Taschen / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — Jodidio updates and supersizes his monograph on starchitect Santiago Calatrava with this XL Taschen production.

Cazú Zegers: Architecture in Poetic Territories by Philip Jodidio (Buy from Rizzoli / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — This is the first major book on Zegers, a Chilean architect “who practices an intensely artistic and ecological form of architecture based on landscapes in which she builds.”

Expect the Unexpected: luis vidal + architects by Philip Jodidio (Buy from Images Publishing / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — The red on the cover of this monograph of Spanish architect Luis Vidal is no accident: it is a signature color that he’s used on projects that include Terminal E at Boston Logan International Airport.

Everlasting Plastics edited by Tizziana Baldenebro, Lauren Leving, Joanna Joseph, and Isabelle Kirkham-Lewitt (Buy from Columbia University / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — (Previously announced in Week 26, this book is actually being released this week.) The team that curated Everlasting Plastics, the US Pavilion at the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale, continues to explore "the infinite ways in which plastics permeate our bodies and our world" with this book of the same name.

Flux: Architecture in a Parametric Landscape by Ila Berman and Andrew Kudless (Buy from ORO Editions/ar+d / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — A sweeping survey of Stacked Aggregates, Modular Assemblages, Pixelated Fields, Cellular Clusters, and other forms that architecture has taken over the last 25 years thanks to the explosion of computational and material technologies.

Invisible by Heather Woofter and Sung Ho Kim (Buy from ORO Editions / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — This monograph presents the works of Axi:Ome, the design practice of Heather Woofter and Sung Ho Kim, from 2015 to 2023.

Nature-First Cities: Restoring Relationships with Ecosystems and with Each Other by Cam Brewer, Herb Hammond and Sean Markey (Buy from University of Chicago Press [US distributor for UBC Press] / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — Recognizing that people and nature are indivisible, this volume “applies the science and practice of nature-directed stewardship to cities.”

Full disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, AbeBooks Affiliate, and Bookshop.org Affiliate, I earn commissions from qualifying purchases made via any relevant links above and below.

Book News:

Palm Springs Life previews The Palm Springs School: Desert Modernism 1934–1975 by Alan Hess, which Rizzoli is publishing in February 2025.

Hyperallergic looks at Mapping Malcolm (Columbia Books on Architecture and the City), a new essay collection that “charts the topography of the political leader’s life and ever-evolving stances toward politics, religion, and love.”

Wallpaper* heaps praise on Atlas of Mid-Century Modern Masterpieces and presents a few images from within the new book by Dominic Bradbury

From the Archives:

I reviewed A Country of Cities: A Manifesto for an Urban America on my blog in August 2013, a few days after Vishaan Chakrabarti gave a talk about it at the Center for Architecture. I wrote that “those in the full-house crowd left with a fairly good understanding of what Chakrabarti envisions for America: dense urban environments served by local and regional rail infrastructure.” A lot has changed in the decade between this book and this week’s “Book of the Week” by Chakrabarti, but while he is still a proponent of cities and their growth, his push for increasing density in cities to the point that they can sustain a subway has subsided; he now embraces lower-density solutions alongside cheaper and easier-to-implement transit, such as buses and light rail. One thing that has remained consistent between the two books is Chakrabarti’s ability, via his writing style and the illustrations he includes, to make architectural and planning concepts understandable to audiences beyond architects and planners. This is important, since the issues he tackles are important to many groups of people, and because he needs the support of politicians, CEOs, and others with power and money to be able to help turn his ideas into reality.

Chakrabarti’s comfort with both buildings and planning reminded me of another architect who created a book of urban planning: Thom Mayne and Combinatory Urbanism: The Complex Behavior of Collective Form, which his own Stray Dog Books put out in 2011. As the cover indicates, the book presents a dozen urban planning projects over a ten-year period. The subtitle also indicates a debt to Fumihiko Maki’s Investigations of Collective Form, though the projects look like Morphosis projects, but at a larger scale, rather than collective efforts. Most interesting to me, as I wrote in 2011, was the way context infused the projects and the way parametric modeling enabled the studio to show the potential evolution of projects over time.

My review concluded: “The smallest [of the dozen projects] is definitely New Orleans Jazz Park, but it is one of the strongest projects in that it illustrates the potential for works of architecture to be influenced by their contexts and in turn improve upon them. What started as a single building is here used as a means to redesign the adjacent park and its civic realm, while also using the space to connect disparate parts of downtown. The post-Katrina context of New Orleans is certainly unique, but it is a strategy that can be applied to many urban projects and sites; architecture is not seen as an object inserted into the city but as something that knits parts of the urban fabric together. This strategy may go beyond what clients are willing to pay for, but it informs design in a way that [the] future of a building's immediate context is considered and a building is open to potential evolutions that are ideally positive and sustainable.”

Thank you for subscribing to A Weekly Dose of Architecture Books. If you have any comments or questions, or if you have your own book that you want to see in this newsletter, please respond to this email, or comment below if you’re reading this online. All content is freely available, but paid subscriptions that enable this newsletter to continue are welcome — thank you!

— John Hill