Typically the “Book of the Week” in this newsletter is a book that was sent to me by a publisher or one I requested from a publisher. Occasionally it is a book I purchased myself, but in all cases it is something that I feel is worthy of being featured atop this newsletter and of being recommended to you, my readers. This newsletter for the week of December 9 features two Books of the Week with two things in common: they were brought to my attention by their respective authors, not their publishers, and both happen to be focused on Nigeria. One is a monograph of a practice that moved from London to Lagos in the 1950s, and the other is a history of a city that is often overshadowed by the megacity that is Lagos. Each book draws attention to overlooked people and places.

Books of the Week:

Who Are Godwin and Hopwood?: Exploring Tropical Architecture in the Age of the Climate Crisis by Ben Tosland (Buy from Birkhäuser / from Amazon / from Bookshop)

The Architecture of the Bight of Biafra: Spatial Entanglements by Joseph Godlewski (Buy from Routledge / from Amazon / from Bookshop)

For better or worse, many architects know Lagos, the largest city in Nigeria, through Rem Koolhaas, who researched the city more than twenty years ago with students from Harvard GSD, a process documented in the 2002 film Lagos/Koolhaas. Joseph Godlewski, a professor at Syracuse University, thinks it is for the worse. In his short contribution to Clog’s Rem issue in 2014, Godlewski calls Koolhaas’s Harvard Project on the City study of Lagos a “miscue” in the way he applied the “culture of congestion” analysis from his 1978 book Delirious New York to the African metropolis. Koolhaas’s “simplistic reading of the city’s seeming ‘self-organization’ from the perspective of a helicopter flyover” is, to Godlewski, “a profound oversimplification of the tremendous challenges facing Lagos’s urban inhabitants on the ground” and is ignorant of the wider economic, infrastructural, and political contexts in the country.

Even though its subject is not Lagos, this critique’s position suffuses Godlewski’s The Architecture of the Bight of Biafra, a scholarly study of the coastal region in Southeastern Nigeria anchored by Old Calabar. While he was initially interested in crafting a case study of the Tinapa Resort in the Calabar Free Trade Zone, the visit Godlewski made to the area in 2010 led him to eventually widen his scope and “take a much deeper historical perspective on the city and the region,” one that “ultimately challenged a number of myths and misconceptions about sub-Saharan Africa.” He also explicitly contests “the ahistorical and apolitical tendencies of Koolhaas’s work,” instead taking a different approach that examines the intertwining — or entanglements, in the author’s preferred term — of market forces and politics.

The resulting urban patterns, or spatial entaglements, in Old Calabar are covered in five thematic yet chronological chapters that span from the 1600s to this century and the Tinapa Free Zone and Resort. Those with an interest in contemporary architecture may only read the fifth chapter, “Zone,” but that is done at the risk of not understanding the bigger picture documented in the “Compound,” “Masquerade,” “Offshore,” and “Enclave” chapters. Godlewski’s text is dense and academic, expounding, for instance, on the historical approaches he used in treatment of his subject, but it is nevertheless clear, readable, and rewarding for patient readers. The audience for the book may be limited, but the author’s approach to his subject, which results in a vivid picture of a relatively unknown place, should be commended. Hopefully it will influence architectural scholarship on other places worthy of similar levels of attention.

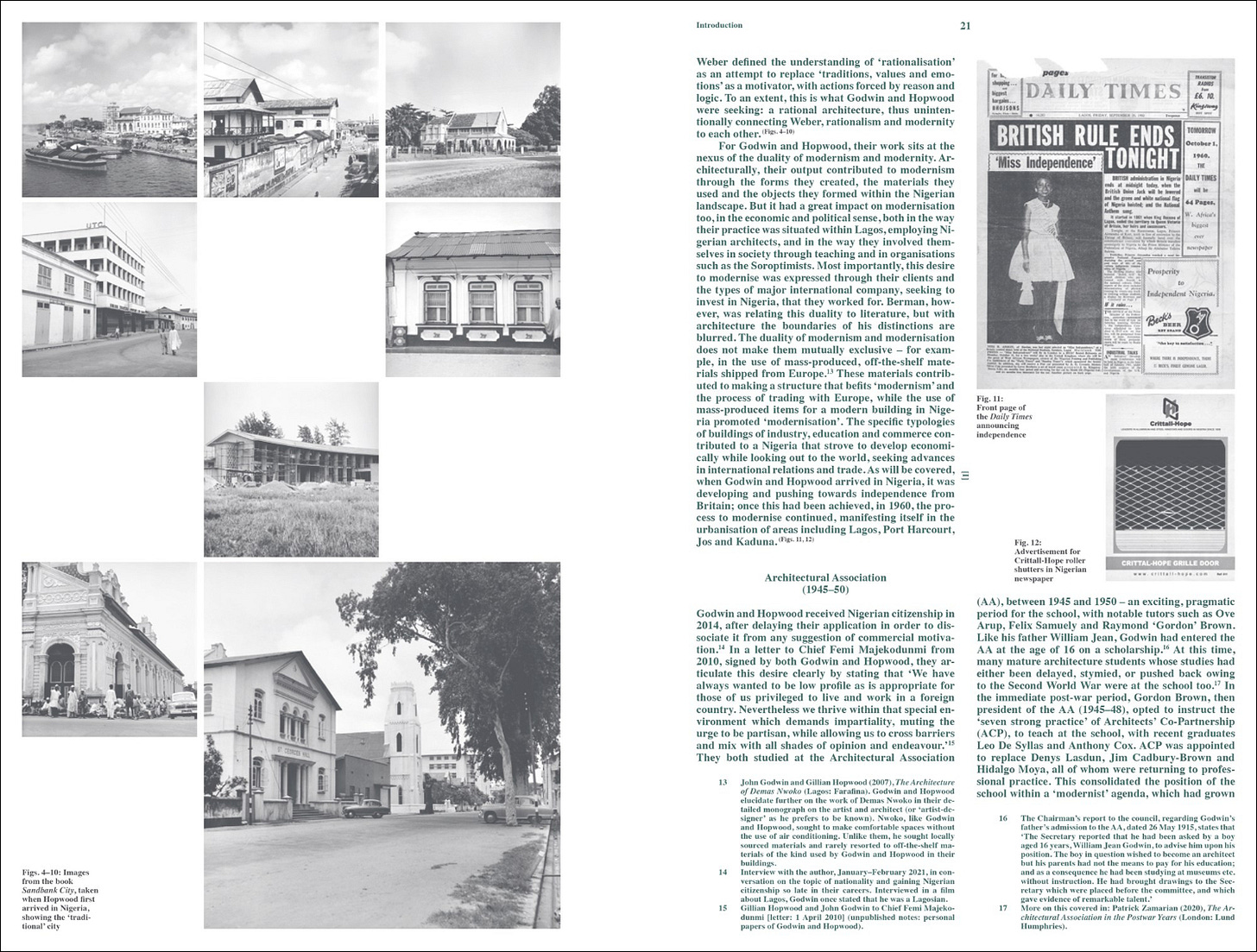

The title of Ben Tosland’s monograph on John Godwin and Gillian Hopwood, Who Are Godwin and Hopwood?, anticipates readers who, like myself, may think of another husband-and-wife UK practice when they hear the term “tropical architecture”: Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry. Fry and Drew’s projects in West Africa were given extensive coverage in The Architectural Review in 1953 and they wrote Tropical Architecture in the Dry and Humid Zones a decade later; evidence of their continued fame into our current century is evident in the couple being the subject of a book-length study in 2014 and being a major part of the V&A’s Tropical Modernism exhibition earlier this year. Although Fry and Drew designed buildings for tropical environs in India and West Africa, they did so remotely, from Britain, via climate data and the application of principles they developed. Godwin and Hopwood, on the other hand, up and moved from London to Lagos in the 1950s and stayed there after Nigeria’s independence in 1960, crafting a successful practice (under different names and with different partners) over roughly sixty years.

Godwin and Hopwood’s attention to tropical architecture — arising from their talents as architects as well as being embedded in the place they were designing for — make them suitable subjects for an in-depth monograph, especially today, when climate-responsive architecture is increasingly relevant. The pair actually reached out to Kent University’s Timothy Brittain-Catlin about a decade ago — not long after they received Nigerian citizenship and had other books of theirs (on architect Demas Nwoko and on Lagos) published — but that effort to make a monograph came to naught. Enter Ben Tosland, who received his PhD in Architecture in 2020 under Brittain-Catlin with a dissertation on European architects working in the Persian Gulf from the 1950s to the 1980s. The overlap between his thesis and Godwin and Hopwood, whose most prolific decades were the same, made Tosland an ideal author for a historical monograph on the expat architects.

Aided by interviews with Godwin and Hopwood before Godwin’s passing in early 2023 at the age of 94 (Hopwood, born one year earlier, is now 97) and a sizable historical archive, Tosland has created a remarkably rich monograph on a practice deserving of more attention. Following a lengthy introduction and a second chapter that situates their practice within various contexts — national, climate, labor, politics, modernity, etc. — the third chapter presents their architecture in four typological sub-chapters: “Residential and Masterplans,” “Building for Industry,” “Constructing an Education System,” and “Office Space.” Tosland admits that, even though Godwin and Hopwood were based in Nigeria, many of their commercial and industrial clients were Western companies (extending even to housing), which makes the chapter on schools flor locals the most exceptional, at least to this reader. Their projects for primary and secondary schools featured rectilinear volumes oriented to prevailing breezes and deep-set glass facades with tilted windows for passive ventilation. As in their wider oeuvre, what appeared like European modernism was inflected to the tropical climate and the lives of the people in Lagos — their own brand of tropical modernism.

Uniting these two books beyond their means of finding their ways into my hands and their Nigerian subjects are two broad areas: globalization and archives. In terms of the first, the authors similarly see global flows as omnidirectional (not just unidirectional, from Europe to elsewhere, as older history’s saw it) and longstanding (not a phenomena that started in the late 20th century); this is a contemporary point of view that is highly relevant in a book on transplant architects and one on a port city. When it comes to archives, the two books are united in the importance of them but are divergent in terms of what the authors had at their disposal. The archive of Godwin and Hopwood is extensive, thanks to the architects keeping just about everything they produced and giving much of it to the CCA in Montreal for safekeeping and accessibility. Archival information on Old Calabar is close to nonexistent, relatively speaking, due in part to historical circumstances, in which buildings and their documentation were treated as impermanent, but it is also fragmentary, with gaps arising based on who was in power and who was doing the documenting. In turn, Bosland’s Who Are Godwin and Hopwood? is loaded with images (some in color on smaller inserts) that are laid out with a graphic design befitting the architects’ bespoke creations, while The Architecture of the Bight of Biafra has fewer images — many of them are photos taken by Godlewski on trips in 2010 and 2012 — that are then fitted into a format consistent with the Routledge Research in Architectural History series. Both books are valuable additions to the growing, much-needed literature on architecture in Nigeria and other parts of Africa.

Books Released This Week:

(In the United States, a curated list)

The African Ancestors Garden: History and Memory at the International African American Museum by Walter Hood (Buy from Phaidon/Monacelli Press / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “The first publication to document the International African American Museum’s landscape design by Hood Design Studio, illuminating its mission and historic site.”

Beyond Architecture: The New New York edited by Barbaralee Diamonstein-Spielvogel (Buy from New York Review Books / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “A volume of new essays by a range of contributors—architectural critics, city planners, historians, scholars, journalists, and more—to commemorate the sixtieth anniversary of the passage of the New York City Landmarks Law, exploring the past, present, and future of historic preservation in America’s great metropolis.”

Building for People: Designing Livable, Affordable, Low-Carbon Communities by Michael Eliason (Buy from Island Press / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Architect and ecodistrict planner Michael Eliason makes the case for low-carbon ecodistricts and presents tools for developing these residential and mixed-use quarters or neighborhoods.”

Bauen im Bestand. Wohnen / Building in Existing Contexts. Living by Sandra Hofmeister (Buy from DETAIL / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “This book chronicles outstanding quality of living conditions that can be created through alterations and conversions, refurbishments, renovations and modernisations carried out on existing buildings.”

Building Sorted by Type: Methods, Materials, Constructions by Dirk Hebel and Ludwig Wappner (Buy from DETAIL / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Single-origin and low-pollutant building materials, which are used in reversible component joints and are simply joined, are the basic prerequisite for the circular design of buildings. This handbook explains how to plan and build according to the circular principle.”

SANAA in Sydney: The Architecture for the Art Gallery of New South Wales edited by Michael Brand (Buy from University of Washington Press [US distributor for Art Gallery of New South Wales] / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — In 2015 SANAA won the Sydney Modern Project, a competition for the expansion of the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Photographs by Iwan Baan highlight this book documenting the project, which opened to the public in late 2022. (This book was previously announced in Week 39/2024 but is actually being released this week.)

Full disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, AbeBooks Affiliate, and Bookshop.org Affiliate, I earn commissions from qualifying purchases made via any relevant links above and below.

Book News:

Yes, there’s still two weeks until Christmas, but Publishers Weekly has its Spring 2025 Fiction & Nonfiction Preview in Art, Architecture & Photography. Highlights are Suspended Moment: The Architecture of Frida Escobedo edited by Max Hollein (The Met, April 2025) and Architecture, Not Architecture by Diller Scofidio + Renfro (Phaidon, February 2025). (Signed copies of the latter are being shipped this week by the publisher, it appears.)

The tenth Graphic Brighton festival, taking place at the University of Brighton (UK) on December 13 and 14, will be exploring the depiction of architecture in comics, under the theme Graphic Architecture.

The Los Angeles Times looks at why “design nerds are obsessed with Architectural Pottery,” the company that is the subject of a new exhibition and book.

The Minnesota Star Tribune has an obituary on Bette Hammel, the “Minnetonka McMansion critic” who “authored several books on architecture and a memoir [Wild About Architecture], some published into her 90s.”

From the Archives:

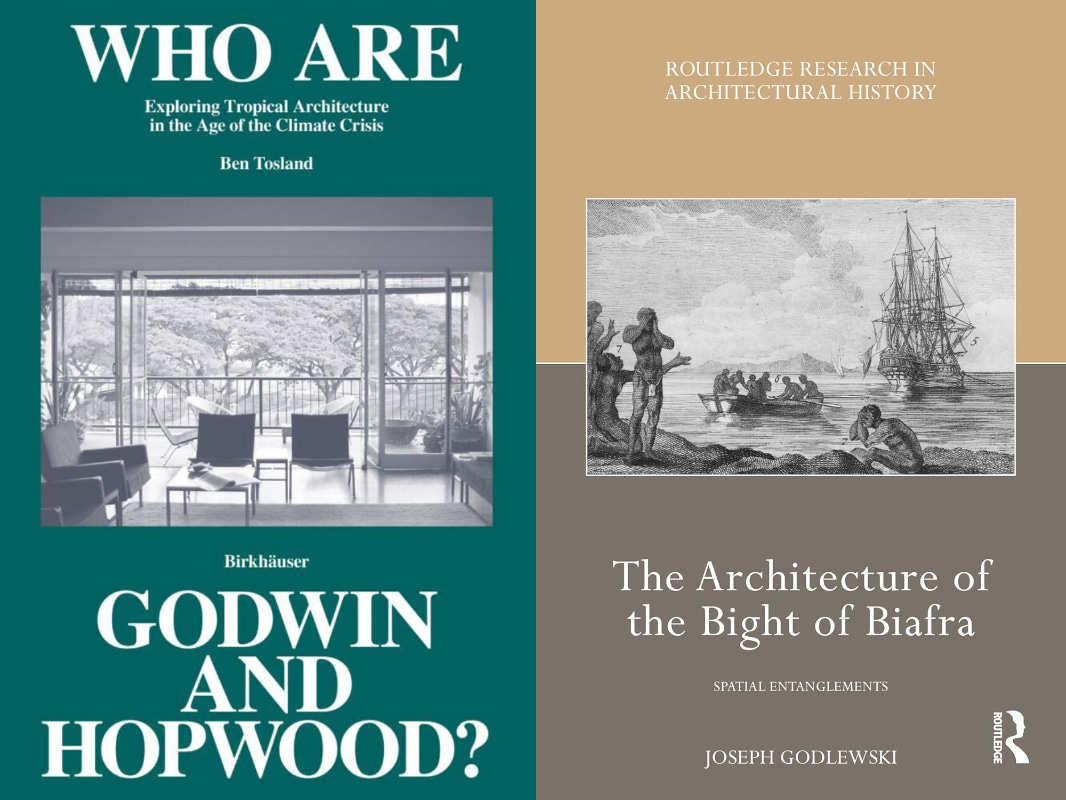

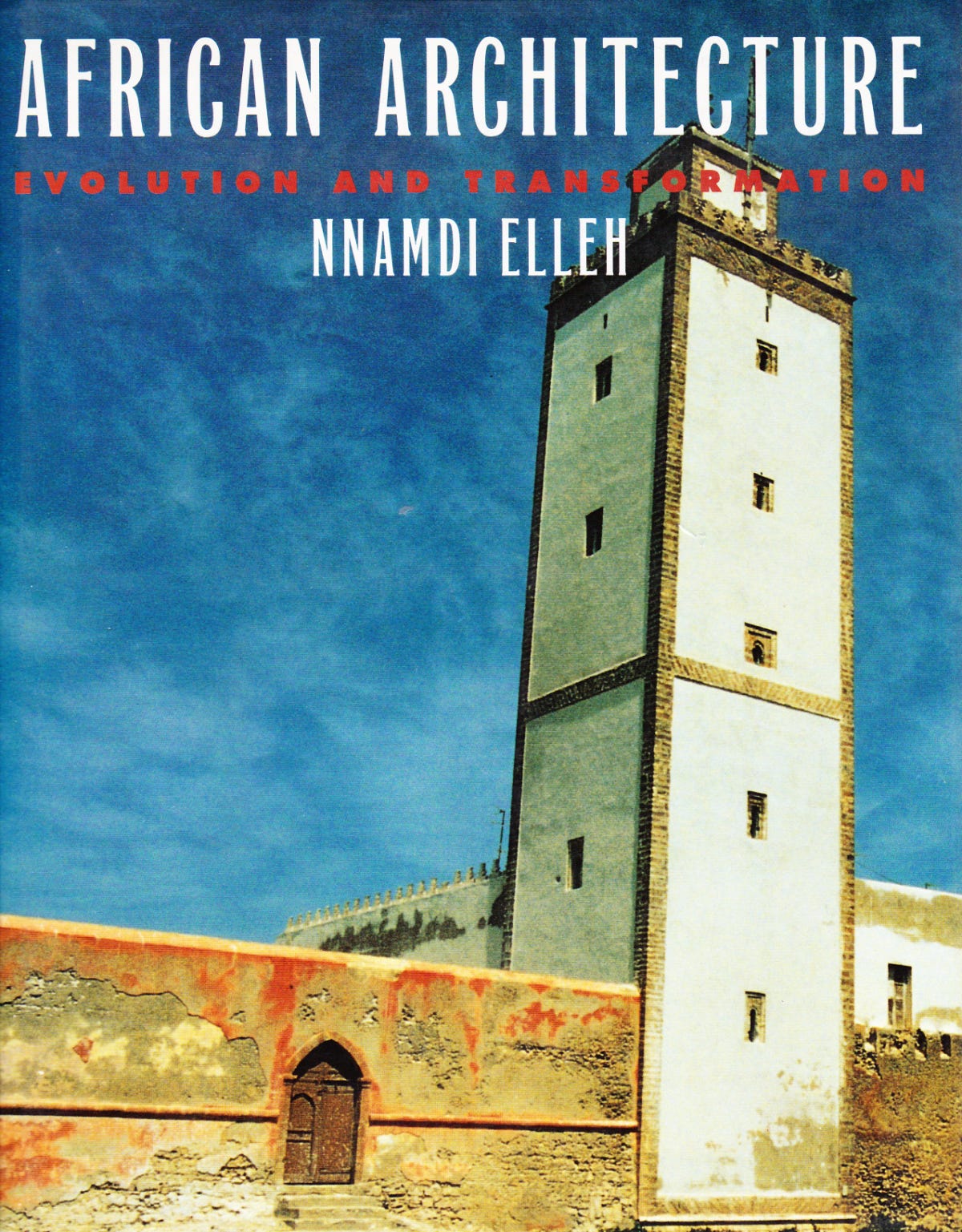

One of the quotes in the back-cover blurb for The Architecture of the Bight of Biafra comes from Nnamdi Elleh, head of the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg and the author of some books on African art and architecture. The one I have in my library is African Architecture: Evolution and Transformation, published by McGraw-Hill Professional in 1996; the book serves as a reference for me when topics of my writing are oriented to the continent. Four of the book’s six parts are geographical, breaking down the country into regions and then devoting individual chapters to single countries or groups of countries. (Illustrating the sweep of the book, the other two chapters are on “defining African architecture” across the centuries and “modern architecture, urbanism, and urbanization.”) Nigeria, like Egypt, Morocco, and South Africa, is given its own chapter, with about a third of it devoted to the Hausa architecture in the country’s North, a third covering Lagos, and a third on the Brasilia-like plan for Abuja, Nigeria’s newly built capital, by Kenzo Tange, et. al. The depth of the last is remarkable — and no surprise, given that another one of Elleh’s books is Architecture and Politics in Nigeria: The Study of a Late Twentieth-Century Enlightenment-Inspired Modernism at Abuja, 1900–2016.

If we consider outsiders’ views of African architecture in the 20th century, few were more prolific than Udo Kultermann, who wrote New Architecture in Africa in 1963, New Directions in African Architecture in 1969, and edited World Architecture 1900-2000 - A Critical Mosaic, Volume 6: Central and Southern Africa in 1999. The last is part of the ten-volume international survey general edited by Kenneth Frampton and published by Springer and China Architecture & Building Press (I wrote about the ten books on my blog in 2017). Algeria, Egypt, Libya, and other Northern African countries are included in Volume 4: Mediterranean Basin, leaving roughly fifty countries for potential coverage in the sixth volume. Yet, unlike Elleh’s book on African architecture, A Critical Mosaic uses a chronological rather than geographical structure, with 100 buildings in each volume painting an architectural portrait of one “region” over the 20th century (with 1,000 buildings around the world, the ten books offer an encyclopedic survey). So, keeping with this week’s newsletter focused on Nigeria, what does this book offer? I count ten projects in Nigeria, most of them coming soon after the country’s 1960 independence and therefore designed by architects from the UK, including James Cubitt, Fry and Drew, Alan Vaughan-Richards, and Godwin and Hopwood, whose Northern Police College (1963) in Kaduna is featured.

Thank you for subscribing to A Weekly Dose of Architecture Books. If you have any comments or questions, or if you have your own book that you want to see in this newsletter, please respond to this email, or comment below if you’re reading this online. All content is freely available, but paid subscriptions that enable this newsletter to continue are welcome — thank you!

— John Hill