This newsletter for the week of October 7 looks at two recently released monographs that are by dramatically different architects — Architecture Research Office and SWA Group’s John L. Wong — but have one thing in common: they are big books. A couple related books from the archive are at the bottom of the newsletter, and in between are a list of six new books and four book-related headlines. Happy reading!

Books of the Week:

The “natural” progression of “traditional” architecture firms has been to begin with small commissions, such as interiors and single-family houses, and progress to larger projects, be they schools, apartment buildings, office towers, or, for the lucky few, museums. This type of growth necessitates hiring more architects and other professionals, such as marketing and finance, and giving up the small projects that established a firm’s reputation. Not all firms pursue this path, but that ones that do seem to get the most attention. In the realm of architecture monographs, there is a similar scaling up that accompanies a firm’s growth: larger page sizes, thicker books, more photography, and higher production values.

My mind is gravitating to size as a barometer in architecture monographs because the two books I’m featuring this week are both large — each has a roughly 9 x 12” paper sizes, is nearly 2” thick, and is more than 400 pages — but are on architects that are quite different: one designs buildings while the other designs landscapes, and one has three partners with around 40 employees while the other has hundreds of employees in eight studios. The biggest difference, book-wise, is that one monograph documents a practice, rather than an individual architect, while the other focuses on a single design partner in a global practice. My review doesn’t focus exclusively on the bigness of these two books, but the “From the Archive” section at the bottom of the newsletter looks at two older books on the same firms, books that happen to be smaller.

Architecture. Research. Office. edited by Stephen Cassell, Kim Yao and Adam Yarinsky, with text by Brooke Hodge (Buy from Delmonico/DAP / from Amazon / from Bookshop)

The name Architecture Research Office, or ARO, clearly indicates which of these two monographs focuses on the practice rather than the partner. ARO was founded by Stephen Cassell and Adam Yarinsky in 1993, after both had worked at Steven Holl Architects, and Kim Yao became partner in 2011. Taken individually, the words that comprise the firm’s name — architecture, research, practice — are so broad as to become universal or even generic, but when combined together they express an ethos. “The name captured our focus on inquiry and engagement carried out in a space that was not merely a location for production,” Yarinsky explains in Brooke Hodge’s lengthy and informative 50-page essay at the beginning of Architecture. Research. Office, released this week by Delmonico and DAP. The importance of the name and the longevity of the principles embedded in the combination of these three words is evident in the title’s use of full stops — but more so by the projects within the book.

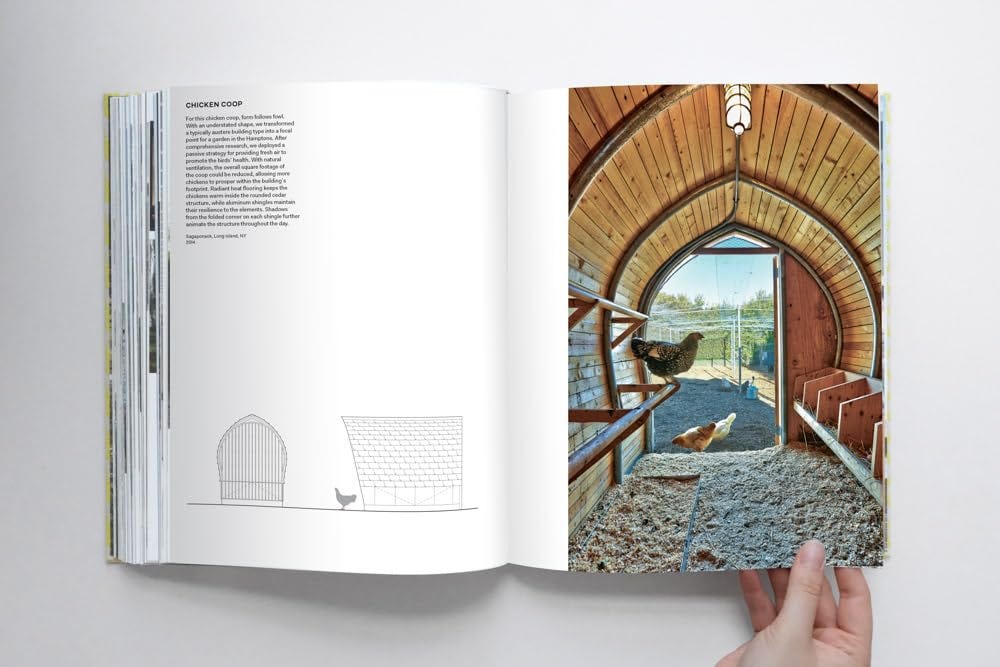

Name any typology (within reason, so no prisons and the like) and most likely ARO has tackled designing a building within it over the last 30 years. Houses, schools, and offices — check, check, and check. Museums, visitor centers, masterplans, landscapes — yes, yes, yes, and yes. A stadium, a synagogue, a boathouse (or two), a chicken coop — all of the above. While the last, the chicken coop, may feel like one of those early-career projects, the one ARO designed for a garden in the Hamptons (spread below) was completed in 2014, more than 21 years after its founding. It is hard not to draw parallels with Frank Lloyd Wright, who was not one to turn down a commission and designed — in his eighties, mind you — a doghouse for the Berger House in San Anselmo, California. In ARO’s hands, the Chicken Coop is a departure from the norm, taking on a bulbous profile, incorporating radiant heat and passive ventilation, and covered with aluminum shingles that have folded corners adding shadow patterns to the home for eight resident chickens, all of whom I’m guessing are content with their home. I’m also guessing most firms, if they even designed a chicken coop, would not include it in a monograph — a type of book that is typically used to market a firm to potential clients, not just document its past accomplishments — but the inclusion here is telling. Documented in photographs and numerous diagrams, the coop illustrations the attention Cassell, Yao, and Yarinsky give to each commission, regardless of size, type, and client/user.

The Chicken Coop is found in “Elevate the Ordinary,” one of six chapters whose titles and corresponding projects articulate the principles driving ARO. The others are “Strategize for Maximum Impact,” “Approach Architecture as a Social Act,” “Engage the Complexity of Contexts,” “Design for Use and Experience,” and “Work with Integrity.” While any architecture firm with design skills and a heart would aspire to these principles, the projects in each chapter manage to live up to their title; the coop elevates the ordinary, for instance, just as Congregation Beit Simchat Torah approaches architecture as a social act. Given the thematic chapters, the 416-page book is not a chronological presentation of ARO’s projects. Normally I might take exception to such an approach, but given the diversity of ARO’s projects over its first 30 years, the time-hopping is far from a distraction. A bonus seventh principle, “Always Keep Learning,” features a conversation between Cassell, Yao, and Yarinsky — a fitting bookend to the projects that mirrors the introductory essay by Hodges and allows the partners to expand on the firm’s name and its enduring principles.

Selected Works of Landscape Architect John L. Wong: From Private To Public Ground, From Small To Tall edited by Oscar Riera Ojeda (Buy from Oscar Riera Ojeda Publishers / from Amazon / from Bookshop)

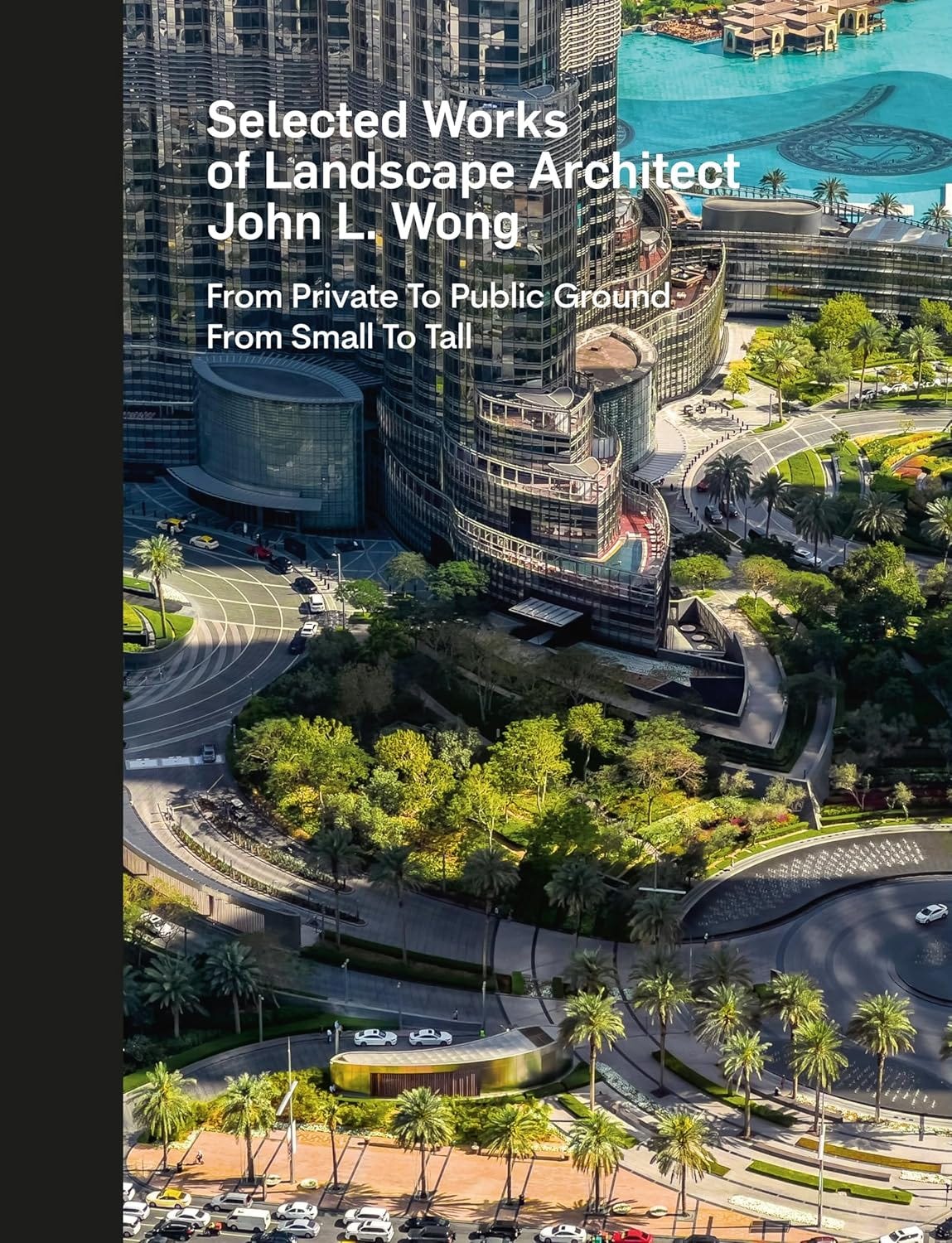

The firm now known as SWA Group was established by Hideo Sasaki and Peter Walker in Watertown, Massachusetts, in 1957. A name changed from Sasaki, Walker and Associates to SWA Group in the 1970s served to “reinforce its emerging group practice philosophy,” one that reflected the firm becoming completely employee-owned and would see both Sasaki and Walker depart to start their own namesake firms early the following decade. One member of the “emerging group” was John L. Wong, who joined SWA in 1976 and is now one of 42 principals across SWA’s eight offices — seven in the US, one in China. Although based in the Sausalito, California office, Wong’s projects are worldwide, as evidenced by the landscape at the base of the Burj Khalifa in Dubai that graces the cover of this hefty, 588-page monograph that was released by Oscar Riera Ojeda Publishers in August.

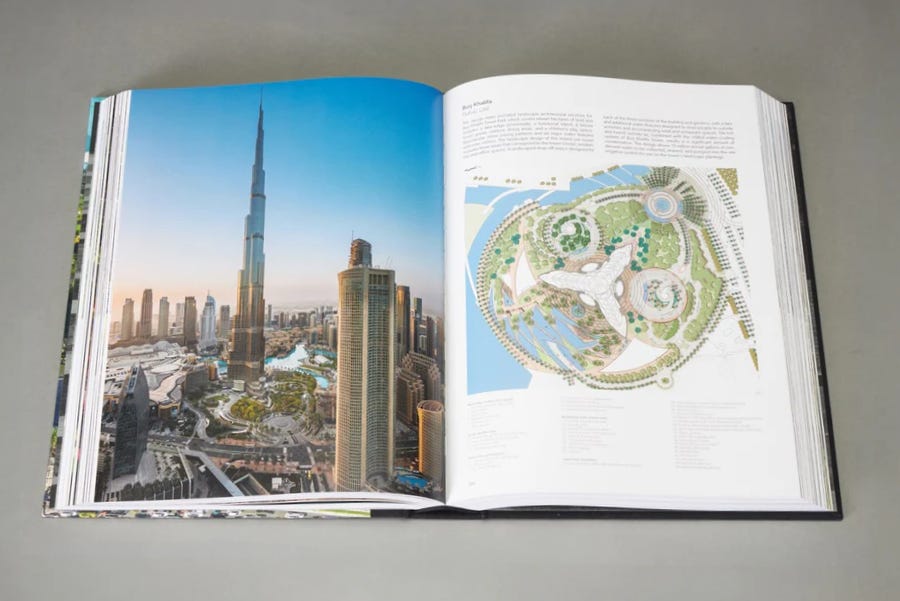

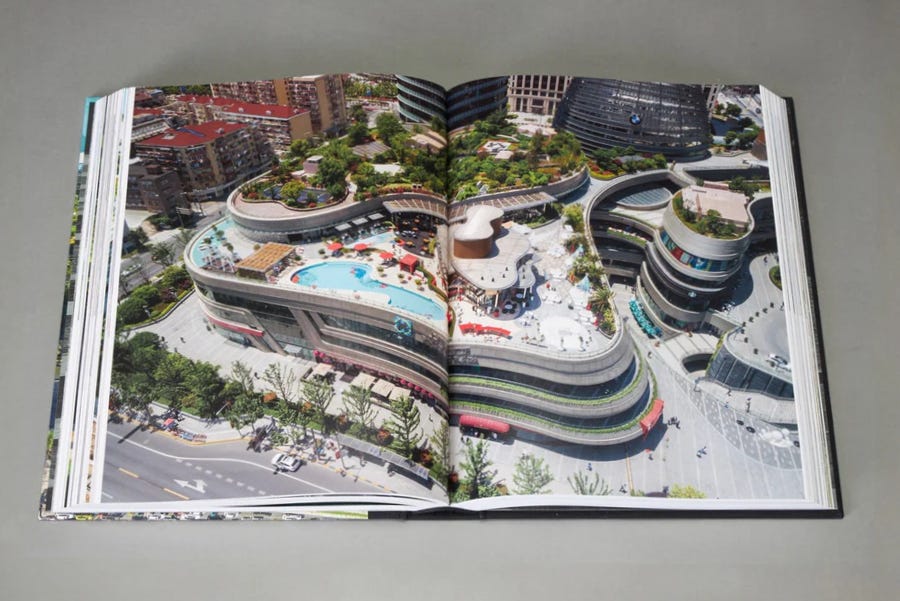

Wong surely has designed hundreds of landscapes in his nearly half century at SWA Group, so the selected works in this monograph are just a smattering, if still many projects across many pages. Wong’s bio at SWA’s website boasts that he has designed “the groundscapes for 12 of the 100 tallest buildings in the world,” so the Burj Khalifa and a few dozen other related projects are included in “Landscape/Groundscape for the World’s Tall and Tallest Structures,” one of the book’s seven chapters. Fittingly, the chapter is introduced by Adrian Smith, who designed Burj Khalifa while at SOM and whose Chicago firm, AS+GG, is a frequent collaborator with Wong (a similar frequency is found with SOM, KPF, and other big firms on par with SWA). The tall-building typology is an interesting one here, given that the skyline profiles and engineering of skyscrapers are usually given the most attention, not how they meet the ground or what the actual shape of that ground is. With 36 projects across more than 160 pages, this chapter alone could have easily been expanded into a standalone monograph, one that would help other architects and landscape architects faced with a similar task and serve to improve the sidewalk-level environments around tall buildings.

The other chapters in the monograph include a collection of sketches he made while a fellow at the American Academy in Rome in the early 1980s, early works, recent works, “Design Responses to Improve Resilience,” and residential gardens. Perhaps the most telling chapter is the third one, “Stanford University and Institutional Project Challenges,” which presents 24 projects across its 114 pages — 20 of the projects are on the Stanford campus that was laid out by Frederick Law Olmsted in the 1880s. Wong has been involved with Stanford for decades, working on projects that range from big to small, from planning to landscape design, all responding to the immediate needs of the school but also tapping into the campus’s original planning principles — principles that were ignored for many decades ahead of his involvement. The Stanford projects are not as glitzy as the landscape that sit at the bases of Burj Khalifa and other supertalls, but they exhibit the range of Wong’s skills and his ability to craft landscapes that are appropriate to their places, purposes, and the people who use them.

Books Released This Week:

(In the United States, a curated list)

Interwar: British Architecture 1919-39 by Gavin Stamp (Buy from Profile Books / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — Stamp, a critic known for his embrace of classical architecture, was working on this “deeply considered account of British architecture in the interwar period,” at the time of his death in 2017. By looking at a variety of styles, he aimed to “[correct] what he saw as the skewed view of earlier historians who were unable to see past modernism.”

Point Line Plane by Kengo Kuma (Buy from Thames & Hudson / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — The prolific Japanese architect’s followup to Architecture of Defeat (Routledge, 2019) is structured as 72 short essays on a variety of topics, all strung together to form a narrative of architectural theory.

Tropicality: Houses by Andra Matin by Andra Matin (Buy from Thames & Hudson / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — This first monograph on “Indonesia's most celebrated and exciting architect,” who has “come to redefine indoor-outdoor living,” presents sixteen houses designed by Matin over the course of the last two decades. (This book was originally listed in Week 38/2024 but is actually being released this week.)

Breuer by Robert McCarter (Buy from Phaidon / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — McCarter, who seems to have a monopoly on pricey Phaidon monographs of 20th-century architects (see my reviews of his books on Louis Kahn and Carlo Scarpa), updates his “most comprehensive” book on architect and designer Marcel Breuer (1902-1981) that was first published in 2016.

Stillness: An Exploration of Japanese Aesthetics in Architecture and Design by Norm Architects (Buy from Gestalten / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — Copenhagen’s Norm Architects presents “their uniquely Scandinavian view of Japanese aesthetics” in this book covering “a decade of travel, study and creative collaboration with Japan.”

Stone Houses by Phaidon Editors (Buy from Phaidon / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — Just like the title says, this book collects “50 stone houses from around the world that make the most of this extraordinary, tactile material.”

Full disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, AbeBooks Affiliate, and Bookshop.org Affiliate, I earn commissions from qualifying purchases made via any relevant links above and below.

Book News:

The Architect’s Newspaper has a review of Matt Shaw’s American Modern: Architecture; Community; Columbus, Indiana written by Eshaan Mehta, an architecture student who, like Shaw, also grew up in Columbus, but whose goal since he was young was “always to get out of town.” (My outsider’s review of the book was in Week 35/3024.)

Fast Company looks at the latest Phaidon atlas, Atlas of Mid-Century Modern Masterpieces, “a definitive visual guide” to mid-century modern architecture around the world.

Charlotte Beach reviews Bowlarama: The Architecture of Mid-Century Bowling at Print Magazine, calling the book by Chris Nichols and Adriene Biondo “a critical historical record that helps keep [the bygone structures] alive.”

Robb Report, suitably, looks at Carchitecture USA—American Houses with Horsepower, the “coffee table book [that] explores the lines between captivating cars and great architecture.”

From the Archives:

I mention above that Architecture. Research. Office. is the second ARO monograph. The first, ARO: Architecture Research Office, was published in 2003, which coincided with the 10th anniversary of ARO, and was part of the New Voices in Architecture series from Princeton Architectural Press and the Graham Foundation. (The series also had titles on Brian MacKay-Lyons, Charles Rose, Della Valle Bernheimer, John Ronan, Julie Snow, Kuth/Ranieri Architects, and Rick Joy, but curiously the ARO book appears to be the only one put out as a hardcover.) At that time ARO was known for the US Armed Forces Recruiting Station in Times Square, so suitably it is the first of seven projects in the relatively petit (7-1/4 x 9-1/2”), 176-page monograph. With so few projects, both built and unbuilt, the depth of presentation is exceptional, with many drawings, diagrams, models, and other illustrations alongside the usual photographs. Filling out the book are essays by Stan Allen, Sarah Whiting, Guy Nordenson, and Philip Nobel, though the “voices” of ARO come across stronger in the book’s highly informative pages.

Selected Works of Landscape Architect John L. Wong is far from the first monograph on SWA Group. The firm’s website lists four others, one of which I reviewed on my blog upon its release in 2011: Landscape Infrastructure: Case Studies by SWA. (Birkhäuser also put out a second edition, as the cover above reflects, in 2013.) The book has a similar page size as the John Wong monograph, but the first edition clocks in at just 184 pages — not much longer than the skyscraper chapter in Selected Works. The shorter page size no doubt reflects how Landscape Infrastructure focuses on that project “type” and the projects coming out of SWA's Infrastructure Research Initiative, which edited the book. Yet, unlike Wong’s monograph, which has a lot of images but very little in the way of text, Landscape Infrastructure has deep case studies on just a few projects, including the Buffalo Bayou Promenade in Houston, the roof of the California Academy of Sciences by Renzo Piano, the Lewis Avenue Corridor in Las Vegas, linear parks such as the Katy Trail in Dallas, and a few mega-projects in Asia.

I wrote that the book did a good job of defining landscape infrastructure (a trendy term at the time) as “a way of designing that integrates infrastructural systems to positively affect both landscape and infrastructure, moving beyond single-use infrastructure developed by engineers,” and I concluded that the book “is especially valuable for articulating a practical position for dealing with infrastructure, at a time when the term still carries old connotations in need of reconsideration.”

Thank you for subscribing to A Weekly Dose of Architecture Books. If you have any comments or questions, or if you have your own book that you want to see in this newsletter, please respond to this email, or comment below if you’re reading this online. All content is freely available, but paid subscriptions that enable this newsletter to continue are welcome — thank you!

— John Hill

After carefully reading the line above about what monographs are —a type of book that is typically used to market a firm to potential clients, not just document its past accomplishments— I can't believe I'd never realized they are, among many other things, great marketing pieces. Great stuff as usual. Thank you!