This newsletter for the week of October 21 looks at two books on Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, the German-American architect who was born Maria Ludwig Michael Mies in 1886 and was simply known as Mies by the time he died in 1969. What can justify two new books on this “master builder”? Read on and see.

Book of the Week:

“Can there be a need for yet another book on Mies van der Rohe, who has been more exhaustively written about than any other of the hero figures of modern architecture?” These words were written in 1975, but they are just as applicable today, nearly fifty years later, when the focus of architecture has shifted from “hero figures” to overlooked architects and collaborations, and is concerned with sustainability and social issues. Yet, two books on Mies are seeing their release in September and October. Although I gather this timing is a coincidence, it seems fitting to review the two books together.

Mies van der Rohe: An Architect in His Time by Dietrich Neumann (Buy from Yale University Press / from Amazon / from Bookshop)

The above quote by British critic J. M. Richards is found in the afterword to Dietrich Neumann’s excellent historical monograph on Mies, when the author is examining Mies’s legacy in books and exhibitions following his death in 1969. Richards was referring to Peter Carter’s Mies van der Rohe at Work, which was published in 1974 and reprinted by Phaidon in paperback 25 years later. The book’s cover features a portrait of Mies holding a cigar to his mouth, in what looks like S. R. Crown Hall, one of his masterpieces. It is a familiar visage that exudes the prevailing view of Mies as pensive, philosophical, almost heroic. Neumann isn’t buying it. The introduction to An Architect in His Time features about a dozen portraits of Mies that span his five-decade-long career; some of the portraits are famous, picturing Mies with his trademark suite and cigar, but Neumann also includes paintings of Mies and a few lesser-known photos from his decades in Germany. This beginning centers the book on Mies the man, but Neumann’s descriptions of the portraits also make it clear how Mies was adept at controlling how the public viewed him as well as his buildings. Put another way, An Architect in His Time justifies its existence by peeling away the mythical layers to find the hidden truths and examine how Mies was viewed by critics and others at the time.

Between the “Portraits of an Architect” introduction and “Legacy” afterword, Neumann looks at every aspect of Mies’s life and nearly every building and project he designed. This is a different approach to, say, Detlef Mertin’s impressive Mies monograph from 2014 and the last update to Franz Schulze’s biography of Mies, done with Edward Windhorst in 2013: both of these earlier books focused on Mies’s masterpieces, with scant or no mention of other, lesser works. Such an approach is understandable, given how many masterworks can be attributed to Mies: Barcelona Pavilion, Villa Tugendhat, Farnsworth House, S. R. Crown Hall, 860–880 Lake Shore Drive, Lafayette Park, Seagram Building, and Neue Nationalgalerie. Some of these buildings are so important they have had multiple books written about them, especially the Barcelona Pavilion, Farnsworth House, Lafayette Park, and Seagram Building. But a book that “presents a new, critical look at Mies and complicates the established narrative about him” — in the words of its publisher, which released the book last month — cannot limit itself to only Mies’s most important works; it must take a broader view that encompasses buildings dismissed both then and since.

Even though Neumann does discuss overlooked Mies buildings, much of the book’s word count is given over to the same masterpieces, with one of its nine chapters devoted entirely to the Barcelona Pavilion — a subject Neumann has a good deal of familiarity with, having done two books on the building in 2020. That chapter falls in the middle of six chapters that cover Mies’s life in Germany, before he emigrated to the United States in 1938 to lead the Illinois Institute of Technology. One could argue that Mies’s influence was most dramatic in the United States, with the boxy office and residential towers that he churned out through his small office and that reshaped skylines around the world as an easy model for other architects to replicate. But the image of Mies as an avant-garde architect, one able to head up a new architecture school in Chicago and take on considerably larger commissions there, was formed by him in Berlin.

A case in point — one that is new to me, and perhaps is based on the considerable new information that Neumann says enabled a fresh look at Mies — is found in the Friedrichstrasse Skyscraper in Berlin, a project most famous for its much published charcoal perspective. While that MoMA link dates it to 2021, when the skyscraper competition took place, Neumann writes, “It was, in all likelihood, never submitted to the 1921 competition for a high-rise in the center of Berlin (as he had claimed), but rather created after seeing the contest’s results,” leading the author to date it to 2022. Not only did Mies make statements indicating he submitted it on time, when his monographic show at MoMA took place in 1947, Mies was labeling the drawing even earlier, to 1919. This is a small bit of data, but it illustrates how Mies crafted his own image and how “God is in the details” of more than just his buildings — it is also in his own words.

Mies in His Own Words: Complete Writings, Speeches, and Interviews 1922–1969 edited by Vittorio Pizzigoni and Michelangelo Sabatino (Buy from DOM Publishers / from Amazon / from Bookshop)

Most architects with even a small library know that, unlike Le Corbusier, Frank Lloyd Wright, Louis I. Kahn (see below) and other “masters of modern architecture,” Ludwig Mies van der Rohe wrote very little. Mies is the subject of many books — probably as many as Corbusier and Wright — but he never wrote one, and finding his own words in magazines, interviews, and other formats is extremely rare. An illustration can be found with the Architectural Association, which hosted an informal conversation with Mies in Bedford Square in 1959, when he was in London to receive the RIBA Gold Medal; the transcript was believed to be lost, but it was not and it was subsequently included in AA Files Conversations, the 2013 book edited by Thomas Weaver.

That conversation is one of the 122 numbered “writings, speeches, and interviews” in Mies in His Own Words, a valuable collection that was edited by Vittorio Pizzigoni and Michelangelo Sabatino and is being released in the US next week by DOM Publishers as the 100th title in its “Basics” series. Pizzigoni and Sabatino met while studying at the IUAV in Venice and both went on to Mies-related futures: Sabatino is a professor at the Illinois Institute of Technology, the Chicago school that Mies headed when he left Germany for the United States in 1938, and whose campus he designed in the following decade. Pizzigoni edited Ludwig Mies van der Rohe: Gli scritti e le parole, a collection of Mies’s writings translated into Italian and published in 2010. The new English-language volume is based on Pizzigoni’s earlier efforts.

The chronological collection of Mies’s writings, speeches, and interviews is widely divergent, ranging from pithy statements just a few lines long to lengthy transcriptions of interviews for magazines or television shows. It includes articles Mies wrote while in Germany, most of them previously translated into English by Mark Jarzombek for Fritz Neumeyer’s The Artless Word: Mies Van Der Rohe on the Building Art (1994), as well as drafts for speeches, informal talks like at the AA, building dedications, lectures, eulogies, many of the aforementioned interviews, and even magazine articles where just a few words by Mies were included. Throughout Mies in His Own Words, Mies’s words are printed in Roman type and those of interviewers and other writers are italicized. That distinction works in theory, but with nearly 250 pages of two-column justified text without breaks between paragraphs, the difference between the two “voices” isn’t strong enough design-wise. (The only illustrations, it should be noted, are portraits of Mies, akin to the introduction of Neumann’s book, inserted between the introductory essays by Pizzigoni and Sabatino and the 122 entries.)

This poor design choice is not a huge issue though, given that this isn’t the kind of book to be read cover to cover; it is a reference and resource for scholars and others interested in Mies to be consulted as needed (helpful in this regard is the inclusion of an index). There are many statements throughout the book that are rich, indicative of Mies’s genius, but there is also a lot of filler, what Neumann refers to in his book as “clichéd and commonplace.” Those with patience to read most or all of the book will be able to trace the evolution of Mies’s voice and ideas over nearly fifty years. For others, for most people,, I recommend focusing on the interviews, many of them found at the back of the book and therefore done late in Mies’s life, when he was reflecting on the influential yet misunderstood principles of his buildings — and reinforcing the stories and myths that would define his life and work for decades to come.

Books Released This Week:

(In the United States, a curated list)

The Henry Clay Frick Houses: Architecture, Interiors, Landscapes in the Golden Era by Martha Frick Symington Sanger and Wendell Garrett (Buy from Phaidon/The Monacelli Press / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “First published in 2001, this acclaimed volume is back in print, shining a spotlight on the four major houses purchased or built and renovated for Henry Clay Frick, the world-famous art collector and steel tycoon.”

The Venetian Facade by Michael Dennis (Buy from ORO Editions / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — This book “explores the art and typology of the Venetian facade, not only as a high point of architectural literacy and achievement, but as a potentially useful contemporary stimulant.” (Originally featured in Week 31/2024, the book’s release date is actually this week.)

Grand Designs at 25: Game-changing designs from the iconic series by Kevin McCloud (Buy from Quarto/White Lion Publishing / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Grand Designs 25 features Kevin McCloud's personal selection of the most significant and memorable builds from 25 years of this acclaimed TV series.”

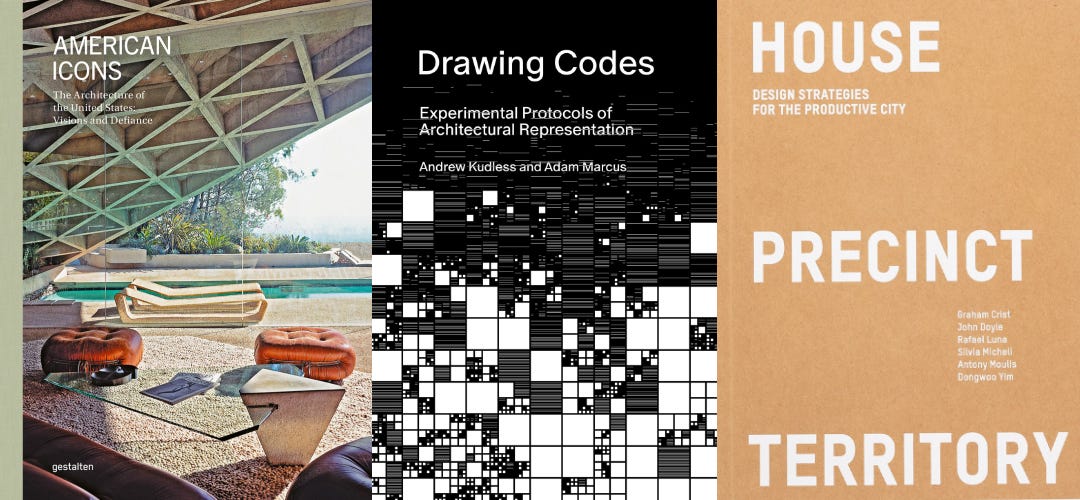

American Icons: The Architecture of the United States: Visions and Defiance edited by gestalten and Sam Lubell (Buy from gestalten / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “American Icons is a testament to the architectural masterpieces of the United States, from residential homes to skyscrapers, from museums to airports, and beyond.”

Drawing Codes: Experimental Protocols of Architectural Representation by Andrew Kudless and Adam Marcus (Buy from ar+d/ORO Editions / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “The book contains 96 commissioned drawings by a diverse range of architects that investigate how rules and constraints inform the ways architects document, analyze, represent, and design the built environment.”

House Precinct Territory: Design Strategies for the Productive City by Graham Crist, et. al. (Buy from ORO Editions / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Working through three scales of analysis, across three cities in the Asia Pacific Region, and deploying varying design research techniques ranging from critical observation to speculative scenario modeling, the book presents a series of projects that seek to retro-fit an existing urban environment with a productive program.”

Félix Candela From Mexico City to Chicago: Rise and Fall of Experimentation in Concrete edited by Alexander Eisenschmidt (Buy from Actar Publishers / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “A collection of essays centers on Félix Candela’s departure from Mexico City and arrival in Chicago during the end of the 1960s and beginning of the 1970s.”

Revitalizing Japan: Architecture, Urbanization, and Degrowth by Mohsen Mostafavi and Kayoko Ota (Buy from Actar Publishers / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “This book features innovative and productive responses, in the form of architectural design and thinking, to the shift in Japan’s social condition under demographic changes that are evident in regional cities.”

Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Independence by Christopher Turner (Buy from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Scrutinizing the colonial narratives surrounding Tropical Modernism, and foregrounding the experience of African and Indian practitioners, this book [from V&A Publishing] reassesses an architectural style which has increasing relevance in today’s changing climate.”

Full disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, AbeBooks Affiliate, and Bookshop.org Affiliate, I earn commissions from qualifying purchases made via any relevant links above and below.

Book News:

The Deutsches Architekturmuseum (DAM) and Frankfurt Book Fair revealed the 10 best architecture books of 2024 last week. Not surprisingly and similar to previous years, eight of the ten winners were published by German and Swiss publishers.

Stir World looks at Iwan Baan’s Rome – Las Vegas: Bread and Circuses, published last month by Lars Müller Publishers.

The 118th issue of OASE, the independent journal for architecture out of The Netherlands, has just been published under the theme “Book Reviews: From Words to Buildings.” It was edited by Christophe Van Gerrewey and Hans Teerds. I’m pleased to say I have a piece in the issue that looks at Michael Sorkin’s review of The Charlottesville Tapes, first published in an issue of Design Book Review, in 1986, but also available in Exquisite Corpse. Download a PDF of the OASE 118 editorial here.

From the Archives:

Dietrich Neumann’s new book on Mies contends that it “[foregrounds] contemporary critics’ responses and the work of Mies’s collaborators and peers” in order to lend a new understanding to Mies’s work. The collaborator that seems to be mentioned the most in the book is Ludwig Hilberseimer, the urban planner and Bauhaus professor that Mies brought with him from Berlin to Chicago in 1938 to teach at IIT, and who appears to have repaid the debt with Mies van der Rohe, a monograph published by Paul Theobald and Co. in 1956. Hilberseimer’s words come across as objective but are laudatory and tread now familiar territory — situating Mies within a lineage of structural innovation, foregrounding technology in modernism, celebrating the proportions of Mies’s designs, and referencing St. Thomas Aquinas, as Mies often did, at least once. Therefore, all these years later the book’s value is found in its abundant images: photographs, sketches, models, floor plans, wall sections, wall sections, and plan details. Not surprisingly, the book omits Mies’s early houses in traditional styles, setting the Friedrichstrasse Skyscraper as the beginning and ending, nearly 200 pages later, with another unbuilt project, his proposal for a convention hall in Chicago.

Mies in His Own Words is hardly the first compilation of an important architect’s written and spoken words. While I’m not sure what the first such book actually was, an important one that came to mind when reading the Mies book by Pizzigoni and Sabatino was What Will Be Has Always Been: The Words of Louis I. Kahn, edited by Richard Saul Wurman and published by Rizzoli and Wurman’s Access Press in 1986. Wurman had previously collaborated with Kahn to publish a folio, The Notebooks and Drawings of Louis I. Kahn, in 1962 (a facsimile was released in 2022); this makes me think of What Will Be as a words-focused yin to the image-saturated yang of the first book. Like the two Mies books atop this newsletter, Wurman begins What Will Be with portraits of Kahn — working, lecturing, reading, talking while being surrounded by fawning young architects. The words that follow are many, 263 pages of them presented in chronological order from the third issue of Perspecta, in 1955, to the second edition of Notebooks and Drawings, from 1973. There is no table of contents or index, so What Will Be is a book to be waded into and read slowly, piece by piece. Those looking for words on specific projects are aided by red lines between passages and the names of projects in the margins. Following the book’s bulk with Kahn’s words are 50 pages of remembrances from architects, critics, and others, and the book ends with another roughly 50 unpaginated pages presenting facsimiles from Kahn’s notebooks. Much of the last, like the notes on the cover, is intelligible to many people today — just one reason why Wurman’s transcribed compilation is such a valuable document.

Thank you for subscribing to A Weekly Dose of Architecture Books. If you have any comments or questions, or if you have your own book that you want to see in this newsletter, please respond to this email, or comment below if you’re reading this online. All content is freely available, but paid subscriptions that enable this newsletter to continue are welcome — thank you!

— John Hill

Thank you, Mr. Hill. I’ve been recently reading Broken Glass by Alex Beam and it’s allowed me to see what an intriguing character MVDR is in every possible aspect of his personal and professional life. By the way, do you have any recommendations on similar books? This one reads almost like an architectural novel, but it’s nonfiction nonetheless and I’d like to read more books like it. Thanks!