This newsletter for the week of October 28 looks at two exhibition catalogs — one for a show I saw in person and one for an exhibition halfway around the world and therefore serving as a substitute to seeing it in person. How do the two catalogs compare, and how well do they transfer the contents of their exhibitions into print for people to alternatively remember what they saw or be an armchair visitor? Following these Books of the Week are the usual new releases and headlines and, at the bottom of the newsletter, two older books on the subjects of the exhibitions, I. M. Pei and Paul Rudolph.

Books of the Week:

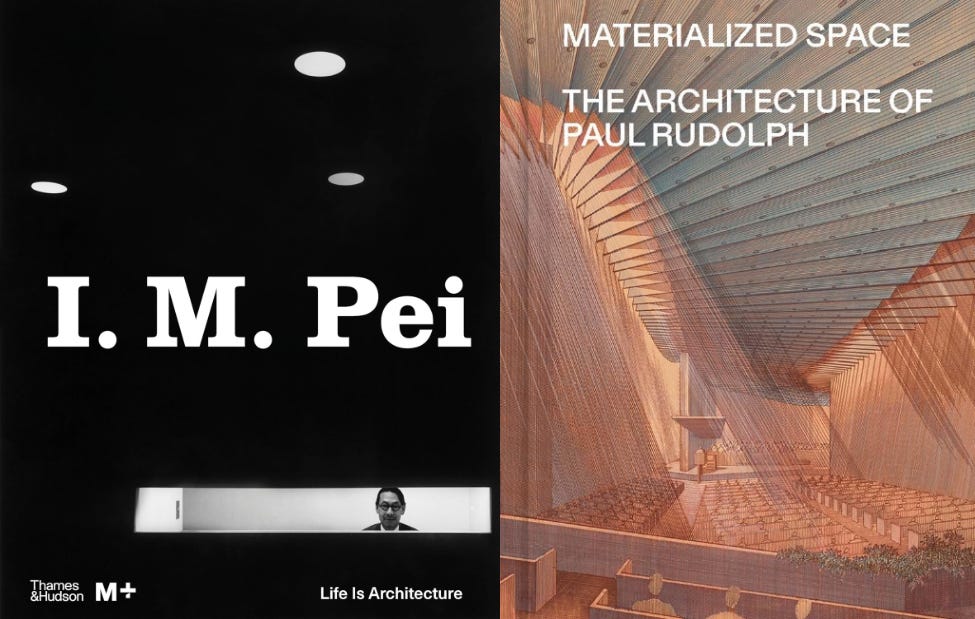

I. M. Pei: Life Is Architecture by Shirley Surya and Aric Chen (Author) (Buy from Thames & Hudson / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — released in September.

Materialized Space: The Architecture of Paul Rudolph by Abraham Thomas (Buy from Metropolitan Museum of Art / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — released this week.

Back in the spring of 2023, during my attempt at doing long-form posts on subjects relevant to architecture rather than doing shorter reviews, I wrote “Architectural Exhibitions and Their Books,” using a few recently published books to explore the form and function of books that were companions to architecture exhibitions. At the time I came down in preference of books that were more experimental, that were not traditional exhibition catalogs, per se, in which color plates from an exhibition were accompanied by scholarly essays. While I still appreciate a catalog that pushes the boundaries to become “an object in its own right,” there is still something to like about more traditional catalogs: namely, the high-quality reproduction of archival images and the depth of research and accessibility of writing found in essays.

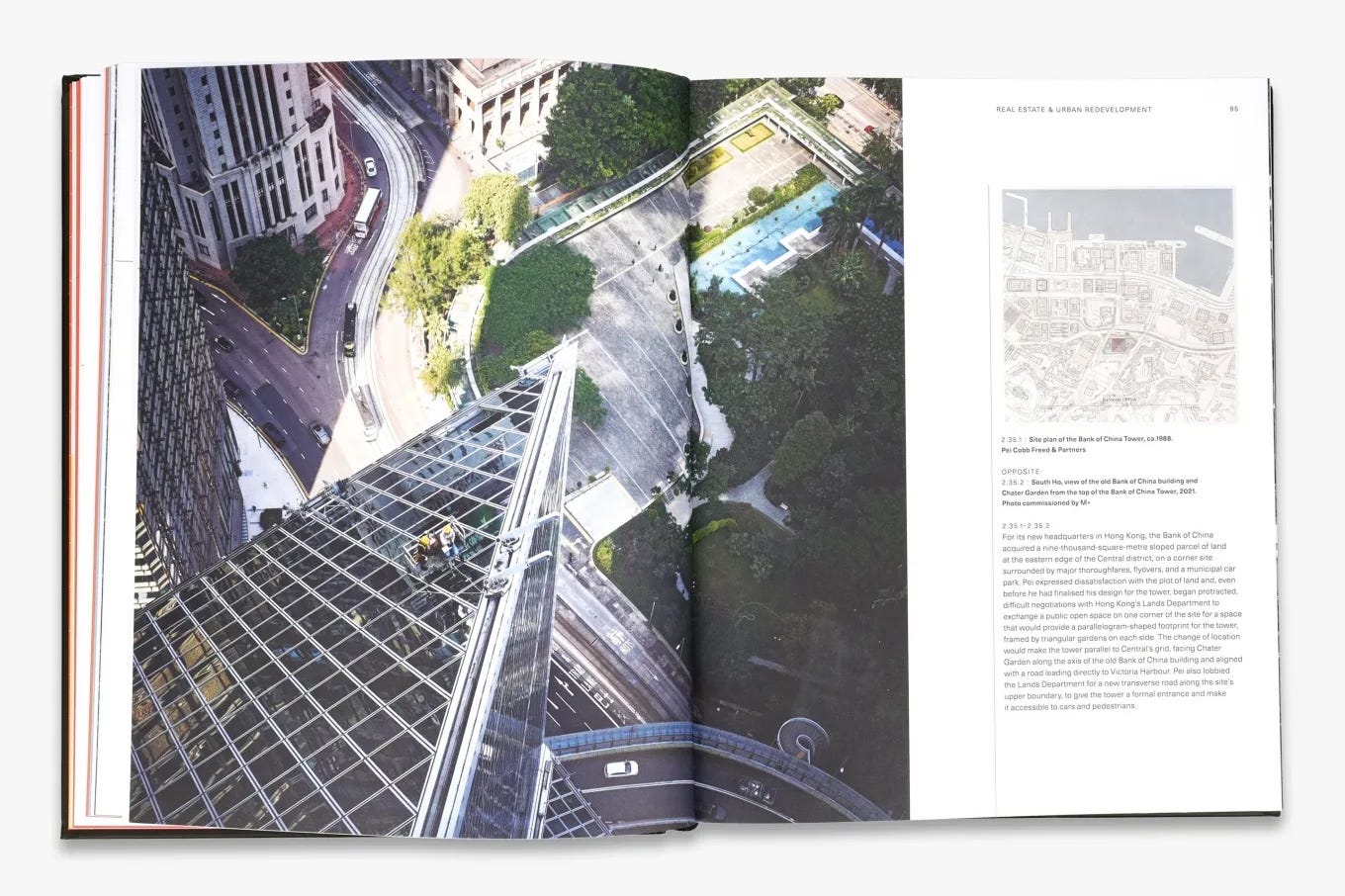

The first of two catalogs that has me looking again at architectural exhibitions and their books is I. M. Pei: Life Is Architecture, the companion to the exhibition of the same name now at M+ in Hong Kong. The major retrospective on the famous Chinese-born American architect was curated by Shirley Surya of M+ and Aric Chen of Het Nieuwe Instituut, both of whom also edited the large 400-page catalog. I have not seen this exhibition in person, but the curators explain in their introduction that the thematic structure of the book’s six chapters corresponds to the same in the exhibition. Basically chronological, each chapter features a short introduction by one of the curators, “a visual narrative drawn from archival documentation,” in their words, and a scholarly essay by an expert in the field. The last includes, for example, “The American Education of I. M. Pei” by Joan Ockman, editor of Architecture School: Three Centuries of Educating Architects in North America, in the book’s first chapter, “Transcultural Foundations”; and “I. M. Pei and Urbanism in North America: 1948–1960” by Eric Mumford, author of Designing the Modern City: Urbanism Since 1850, in the second chapter, “Real Estate & Urban Redevelopment.” Furthermore, sprinkled throughout the book are new photos specially commissioned by M+ that provide new views of Pei’s famous buildings, like this view from the top of the Bank of China tower:

Most valuable is the archival documentation, the breadth of which ranges from I. M. Pei’s student work at MIT and Harvard, clippings from newspapers and magazines, and portraits of Pei to the usual drawings, renderings, and photographs of buildings designed by Pei over the course of six decades. Most of the images are accompanied by captions that range from one or two to about a dozen sentences; combined with the occasional snippets culled from the Rethinking Pei symposium held at Harvard GSD in 2017, the captions help turn the archives into a narrative, as the curators intended. One could read the captions solely and glean a thorough understanding of Pei’s long life and prolific career. Assuming the same captions are used as wall text at M+, the same reading could happen at the exhibition, but the format of a book — and the ability to reference it long after reading it — make it particularly well-suited to such a visual narrative. (For a more traditional, biographical narrative of Pei, see the bottom of this newsletter.)

The second catalog, Materialized Space: The Architecture of Paul Rudolph, accompanies the exhibition of the same name now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. It is notably the first exhibition at the Met on 20th-century architecture since one devoted to Marcel Breuer in 1972, and it is billed as “the first-ever major museum exhibition to examine the career of the influential 20th-century architect Paul Rudolph.” The Met’s Abraham Thomas, formerly of the Sir John Soane’s Museum in London, and appointed to the Met in 2020, is the curator. Thomas admitted during a press preview to sensing an overlap between Soane’s spatially dramatic creation and Rudolph’s own labyrinthine penthouse at 23 Beekman Place. Thomas therefore approaches Rudolph with an eye toward form and materials, an understanding of the architect’s skills at shaping space, and a desire to present the whole of Rudolph’s career; the title Materializing Space, hints at some of this. As I wrote in my review at World-Architects, while this approach is at the detriment of understanding other aspects of Rudolph’s life and taking a strong position toward saving his at-risk buildings, overall the exhibition is a solid introduction to Rudolph’s architecture, from his early houses in Florida, his famous Brutalist buildings in the 1960s and 70s, and shiny interiors like 23 Beekman Place, to the tall buildings he built in Singapore and other Asian cities toward the end of his life (see bottom for more on the last).

The catalog — at 128 pages, relatively small and slim compared to the Pei book — is, like the exhibition, solely attributed to Thomas. Outside of the foreword by the director of the Met, Thomas wrote every part of the book, which, like the Pei book, is partitioned into six chapters that parallel the structure of the exhibition. Following a concise introduction that readies readers for the half-dozen thematic chapters, Materialized Space basically moves chronologically through Rudolph’s career. Thomas describes important projects in each chapter (Modern Houses, Megastructures, Projects in Asia, etc.) but gives most of the pages over to Rudolph’s instantly recognizable drawings, most of them culled from the Rudolph archive at the Library of Congress, alongside numerous photographs and magazine clippings. Yet, given that Rudolph actually drew the famous perspectives and perspectival sections (he didn’t parcel them out to employees, in other words), and he drew them large, the drawings in the book pale in comparison to seeing them in person. Likewise, the exhibition features a compilation of clips from films set in Rudolph’s buildings or inspired by them, media that can only be mentioned briefly in the book. The films illustrate how Thomas crafted an exhibition that introduces Rudolph to non-architects and others not familiar with him or his buildings. With its single voice and short texts, the book does the same — and does it fairly well.

Books Released This Week:

(In the United States, a curated list)

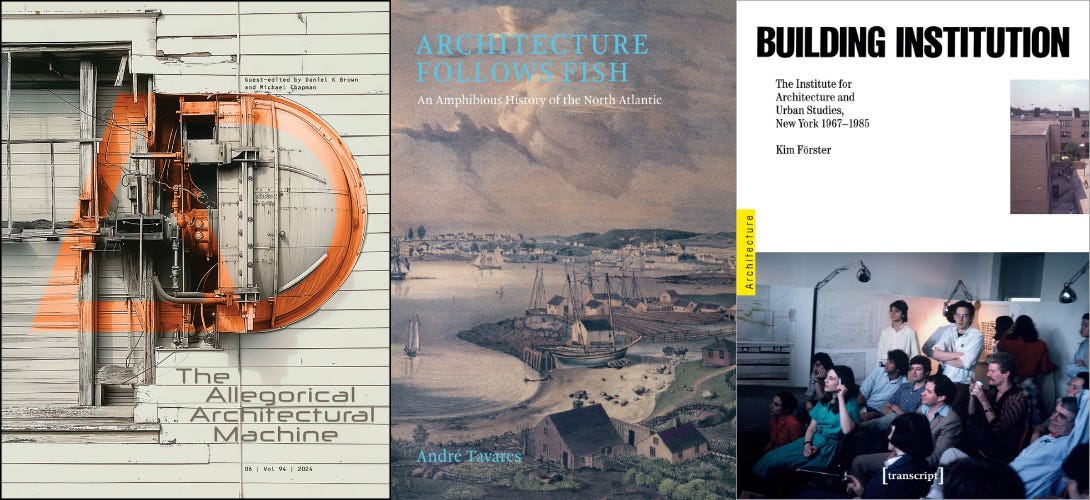

The Allegorical Architectural Machine edited by Daniel K. Brown and Michael Chapman (Buy from Wiley / from Amazon) — The latest issue of AD “considers the influence of the machine as an allegorical device for exploring alternative architectural practices, and includes a cross-section of viewpoints from emerging and established international practitioners and academics.”

Architecture Follows Fish: An Amphibious History of the North Atlantic by Andre Tavares (Buy from The MIT Press / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “A highly original exploration of the history of architecture in relation to fish, shedding light on the connection between marine environments and terrestrial landscapes.”

Building Institution: The Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies, New York 1967-1985 by Kim Förster (Buy from Columbia University Press [US distributor for transcript publishing] / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Drawing on extensive archival research and oral histories, [Foster] constructs a collective biography that details [IAUS’s] diverse roles and the dynamic interplay between research and design, education, culture, and publishing.”

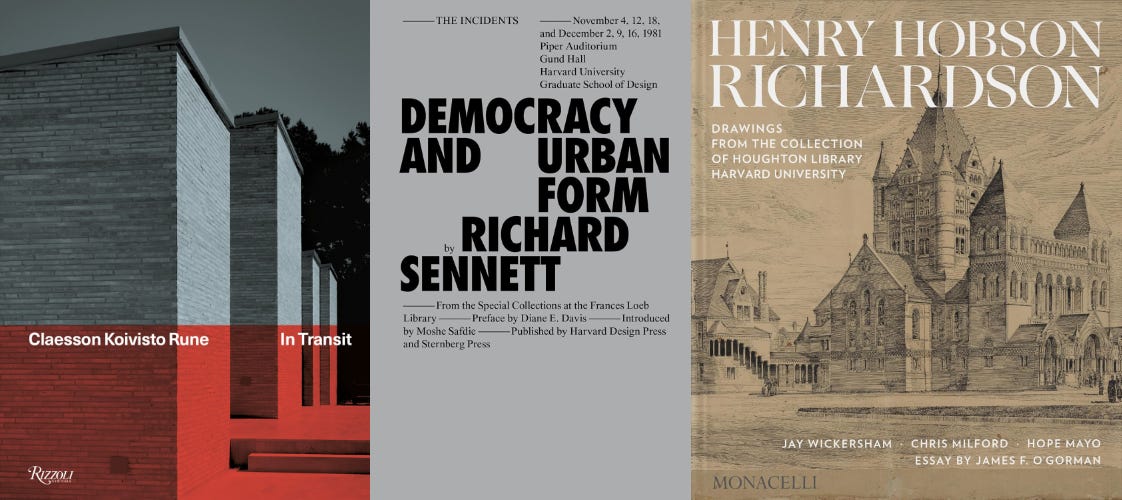

Claesson Koivisto Rune: In Transit by Gustaf Kjellin (Buy from Rizzoli / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “This is the first comprehensive monograph on the philosophy and works of architecture and design office Claesson Koivisto Rune, one of Sweden’s most internationally recognized and awarded architecture and design offices today.”

Democracy and Urban Form by Richard Sennett (Buy from The MIT Press [US distributor for Sternberg Press] / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Over a series of six lectures [at Harvard GSD in 1981], Sennett presented discourse as the foundation of democracy, and posited that our cities are uniquely positioned to either empower or constrict this discourse—and that the difference could lie in architecture and urban design.”

Henry Hobson Richardson: Drawings from the Collection of Houghton Library, Harvard University by Jay Wickersham, et. al. (Buy from The Monacelli Press/Phaidon / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “The first in-depth publication of drawings that reveal the creative genius of H. H. Richardson, the greatest American architect of the nineteenth century.”

Liminal House: McLeod Bovell (Buy from Oscar Riera Ojeda Publishers / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — The latest book in the Masterpiece Series delves into McLeod Bovell’s Liminal House, which “straddles a […] threshold between West Vancouver’s natural stony seashore and its suburban residential neighborhood.”

STUDIO 804: Detailing Sustainable Architecture edited by David Sain (Buy from Oscar Riera Ojeda Publishers / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “This book provides in depth, detailed studies of the drawn and constructed methods developed by [KU’s Studio 804] to help inform the industry as to how Studio 804 has produced sixteen consecutive LEED Platinum buildings to date.” (See also my review of the earlier Studio 804: Design Build. Expanding the Pedagogy of Architectural Education.)

The Well-Designed Accessory Dwelling Unit: Fitting Great Architecture into Small Spaces by Lydia Lee (Buy from Schiffer / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “An inspirational look book for conceiving, planning, and building an accessory dwelling unit (ADU), a small house that is on the same property as the main house — a quickly growing trend that is transforming our vision of what a dream home should be.”

Full disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, AbeBooks Affiliate, and Bookshop.org Affiliate, I earn commissions from qualifying purchases made via any relevant links above and below.

Book News:

Guardian columnist Simon Jenkins writes about “why the people finally rose up against ‘sod you architecture,’” in what looks to be a teaser for his forthcoming A Short History of British Architecture: From Stonehenge to the Shard.

Matt Shaw, author of American Modern: Architecture; Community; Columbus, Indiana, reviews Ferda Kolatan’s Misfits & Hybrids: Architectural Artifacts for the 21st-Century City, whose titular pair “can offer new forms that operate within the systems of regulation that quietly govern the forms of the city — familiar and unfamiliar.”

Anyone Corporation, the publisher of Log headed by Cynthia Davidson, is selling a bunch of old books and magazines on AbeBooks, ranging from $10 monographs to $900 issues of Archigram.

“Writer Underwriting Writer,” an article at Northwestern detailing how architecture critic Blair Kamin has funded his successor at the Chicago Tribune and how Edward Keegan’s role is different than Kamin’s.

From the Archives:

Biographies of architects are rare compared to other walks of life, but those that exist tend to arrive after the subject has passed, as in Robert C Twombly’s, Brendan Gill’s, and Ada Louise Huxtable’s biographies of Frank Lloyd Wright, Mark Lamster’s biography of Philip Johnson, (the same would have applied to Franz Schulze’s “official” biography of him, but Johnson lived so long he allowed the publication of Schulze’s book earlier), or Carter Wiseman’s “in-depth biographical study” of Louis I. Kahn, published in 2007, more than 30 years after Kahn’s death. Few architects are as famous as, say, Frank Gehry, to warrant biographies in their lifetime. Besides Paul Goldberger’s 2015 book on Gehry, released when the architect was 86, another notable example is Wiseman’s earlier biography, I.M. Pei: A Profile in American Architecture, published by Harry N. Abrams in 1990, when Pei was 73 years old.

Pei retired from practice that same year, making the timing logical, though he continued to design buildings as a consultant until 2008 (he died in 2019 at 102 years old). Pei retired at a high point of sorts, one year after the opening of the controversial but now beloved Louvre Pyramid. That project is the subject of one of the book’s twelve chronological chapters — most of them using important Pei projects to tell his story — coming right before the last chapter, “1989: ‘The Year of Pei.’” I’ll admit that I’ve only read parts of Wiseman’s biography but enough of it to grasp how accessible it is to a wider audience, regardless of its monograph-like focus on projects and abundance of drawings and photographs. Unfortunately, at least for this 51-year-old, and based on the book’s first edition, the choice of font — narrow, with thin horizontals and diagonals — is terrible, making it hard to read the accessible text.

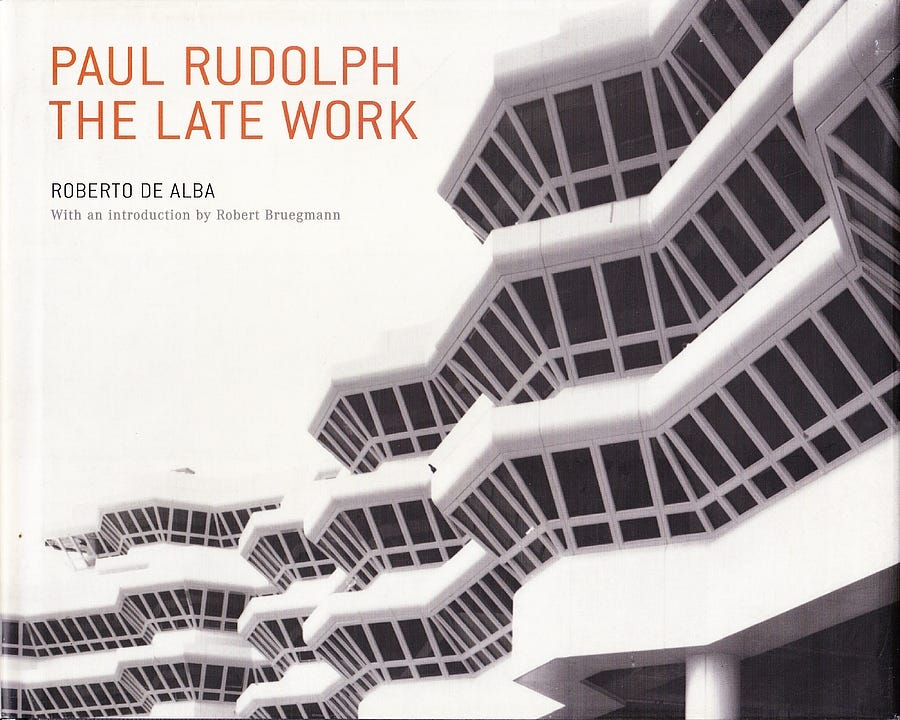

About twenty years ago, Princeton Architectural Press planned a “three-volume set of the complete works of […] legendary architect Paul Rudolph.” Best I can tell, only two were made: Paul Rudolph: The Florida Houses by Christopher Domin and Joseph King in 2002, and Paul Rudolph: The Late Work by Roberto De Alba in 2003. Missing is the book devoted to the in-between years, when Rudolph made outlandish proposals, such as the Lower Manhattan Expressway, and designed his most famous buildings, including the Art and Architecture Building at Yale. I’m not sure what derailed the series from reaching completion, but if The Late Work, which I have, is any indication, the two extant books are valuable for their extremely thorough visual presentations of Rudolph’s prolific output. The Late Work presents just that: buildings and projects designed between 1969 and his death in 1997.

Following a lengthy and informative introduction by historian Robert Bruegmann are three typological chapters with 27 buildings and projects: Houses; Towers; and Housing, Institutions, and the City. For anyone who visited the Met exhibition and was intrigued by Rudolph’s own house, the towers he designed for Asian cities, and other projects done late in his career, when his reputation was at a low point but his designs were still formally inventive, they will appreciate this book, which includes a number of lesser-known houses and has an abundance of Rudolph’s colored-pencil sketches on projects that never left the drawing board. If the thorough presentations weren’t enough, The Late Work also includes Peter Blake’s ca. 1996 interview with Rudolph at 23 Beekman Place, accompanied by the architect’s well-known diagrams of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion.

Thank you for subscribing to A Weekly Dose of Architecture Books. If you have any comments or questions, or if you have your own book that you want to see in this newsletter, please respond to this email, or comment below if you’re reading this online. All content is freely available, but paid subscriptions that enable this newsletter to continue are welcome — thank you!

— John Hill