This newsletter for the week of December 16 heads to Houston … and Sandpoint and other places where zoning (or a lack thereof) has made an impact, via Sara C. Bronin’s Key to the City: How Zoning Shapes Our World. At the bottom of the newsletter are two other books related to this “Book of the Week,” while the usual headlines and new releases are in between. Next week I’ll have a shorter newsletter featuring a list of my favorite books of 2024. Happy reading!

Book of the Week:

Key to the City: How Zoning Shapes Our World by Sara C. Bronin (Buy from W. W. Norton / from Amazon / from Bookshop)

Since learning about it earlier this year, I’ve been waking up every morning, making a cup of coffee, and playing Unzoomed alongside Wordle, Connections, and other once-a-day games. Developed by Benjamin Td, Unzoomed appropriately starts at a zoomed-in aerial view of a city free of labels, and with each incorrect guess the satellite view zooms back a little bit and gives a hint on how far away one’s guess is from the city in question. Name the city correctly within six guesses and you win. As I wrote about it back in May, “the game asks that we take an educated guess based on various factors: recognizable buildings, street patterns, roof colors and materials, types of trees and tree coverage, bodies of water, the directions of shadows, even image quality.” It’s not too difficult to know the hemisphere or continent on that first zoomed-in view, but it’s a little harder to nail down the country — except for the United States, whose downtowns with numerous blocks devoted to surface parking are a dead giveaway. No wonder then that Td created an Unzoomed USA Edition, which (I think) includes more American cities to choose from than regular Unzoomed, forces people to think about region or state on that first guess, and hones in on suburban or exurban areas that make the game tricky to win in one or two guesses. To wit, a recent day featured what looked like a sparsely populated Midwestern city but ended up being … Staten Island!

I’m thinking of Unzoomed, and the USA version in particular, in the context of Sara C. Bronin’s Key to the City because that characteristic of most US cities — parking, parking, and more parking — while it can be chalked up to the wider structure of the American landscape and the need to get around via automobile, can also be attributed to zoning: the local laws that determine what uses can be built where, how big, and how tall. Zoning also determines other things that get built (or not), including parking. No instance of this requirement in Bronin’s book is more telling of the current state of affairs and the need for an overhaul of zoning in towns across the United States than a bank in the town of Sandpoint, Idaho (population 8,300), being put in a situation where it bought and tore down historic buildings in order to create 118 more parking spaces as part of a building expansion. Zoning dictated “a parking space for every few hundred square feet of the bank” but resulted in the loss of old buildings, the eviction of small business, the loss of tax revenues from the same, and more asphalt. Thankfully, people in the town realized the error of its ways and the town overhauled its code to, among other things, eliminate parking minimums in its downtown.

The brief story about Sandpoint falls in a chapter about cars and parking alongside longer accounts of how zoning impacts — for better or worse — other American cities. Instead of New York City and other big cities famous for their zoning codes, Bronin takes us to smaller cities and towns, most that she is familiar with. So readers learn about Hartford, Connecticut; Buffalo, New York; Scottsdale and Tucson, Arizona; and Austin and Houston, Texas. You might now be asking, “Why Houston? It famously doesn’t have zoning.” Indeed it does not, but Bronin grew up there so is very familiar with this flip side of zoning, including how certain pockets that actually are zoned compare to the majority without zoning, and how the covenants of many neighborhoods, though not explicitly called zoning, actually do many of the same things that zoning does, such as determining minimum lot sizes and setbacks for residential areas. Houston is in fact where Bronin begins the book, and when it comes time for her conclusion 150 pages later, she addresses the “laissez-faire, market-based” voices that advocate for zoning’s abolition and use Houston as an exemplar. But readers know by this point that Bronin — an architect, attorney, and policymaker based in Washington, DC — does not agree. She believes that “sensible reforms” to zoning can reverse car-focused policies, boost local economies, and even improve racial and economic inequality, among many other things.

Bronin is a true believer in zoning and Key to the City is her argument. It is a very readable argument, with the bite-sized accounts of zoning’s impact on American cities making what is admittedly a boring subject for many people much easier to digest. That said, I wish the author and publisher would have opted for an illustrated book instead of one without a single photograph, map, or diagram. The author’s descriptions are good at conveying how zoning has made positive and negative changes to places, such as with the bank in Sandpoint, but letting readers see that change — through before and after photos, in this case, or solid/void diagrams of buildings vs. parking — would, I think, strengthen Bronin’s arguments, help structure the text, and even enliven it. Most importantly, photos and other images would also accentuate how zoning impacts the physical character of neighborhoods — and literally express “how zoning shapes our world.”

Books Released This Week (and in the Next Two Weeks):

(In the United States, a curated list)

A few books released this week:

Against the Grain: Mass Timber in the Home by William Richards (Buy from Schiffer Publishing / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “A collection of inspiring homes for design enthusiasts that puts renewable ‘mass timber’ front and center as a unique, and beautiful, solution to the challenges of climate change.”

The Barrack, 1572–1914: Chapters in the History of Emergency Architecture by Robert Jan van Pelt (Buy from University of Chicago Press [US distributor for Park Books] / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “The Barrack, 1572–1914 tells the little-known history of a building type that many people used to register as an alien interloper in conventionally built-up areas […] a mostly lightweight construction, a hybrid between a shack, tent, and traditional building.”

CARTHA—Building Identity by Francisco Moura Veiga, et. al. (Buy from University of Chicago Press [US distributor for Park Books] / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Explores the role of architecture in forming identity in society through interviews with renowned scholars and a set of projects by international firms especially designed for this book.”

Second-Order Preservation: Social Justice and Climate Action through Heritage Policy by Erica Avrami (Buy from University of Minnesota Press / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “A critical reassessment of historic preservation policies in the United States, Second-Order Preservation brings needed attention to the hierarchical underpinnings and effects of established preservation frameworks, [… questioning] the criteria by which value is ascribed to historic buildings and neighborhoods […]”

And a few more books released in the next two weeks:

Architecture Follows Climate: Traditional Architecture in the Five Climate Zones by Alexandros Ioannou-Naoum (Buy from Birkhäuser / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Architecture Follows Climate provides the first in-depth and comprehensive overview of passive building techniques that have been tried and tested for centuries.”

Contemporary Michigan: Iconic Houses at the Epicenter of Modernism by Peter Forguson (Buy from Visual Profile Books / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “Residents of Detroit, and indeed the entire state of Michigan, have been living with some of the finest work by such Modern masters as Frank Lloyd Wright, Mies van der Rohe, and Eliel Saarinen since the dawn of the 20th century.” This book, a follow-up of sorts to Forguson’s Detroit Modern: 1935–1985 (2022), features more of them.

The Great Repair: A Catalog of Practices by ARCH+ (Buy from Spector Books / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “The second volume in The Great Repair series presents a panorama of approaches that foreground methods of repair as the design paradigm for a new material culture. […] This catalog builds upon the 2023 book The Great Repair: Politics for the Repair Society, which provides the theoretical basis for this practical manual.”

Visible Upon Breakdown: Exploring the Cultural, Political and Spatial Nature of Infrastructure edited by Christoph Miler and Isabel Seiffert (Buy from Spector Books / from Amazon / from Bookshop) — “From the war in Ukraine disrupting wheat exports to Covid and wood shortages affecting construction sites worldwide, this volume questions the cultural, political and spatial nature of infrastructure, investigating its tangible components alongside the faults that appear when those systems fail.”

Full disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, AbeBooks Affiliate, and Bookshop.org Affiliate, I earn commissions from qualifying purchases made via any relevant links above and below.

Book News:

Bill Millard digs deep into Vishaan Chakrabarti’s The Architecture of Urbanity: Designing for Nature, Culture, and Joy at Common Edge. (My review was in Week 39/2024.)

Scroll down this article at ArchitectureNow to see the winners of the Architecture Book of the Year Awards that were announced on December 10 in London. (I haven’t seen a list of winners anywhere else, not even on the award’s website.)

Sofia Albrigo muses on the philosophy of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe at Brooklyn Rail, in the context of Mies in His Own Words, edited by Vittorio Pizzigoni and Michelangelo Sabatino. (My review was in Week 43/2024.)

In a fairly long Architectural Digest article with lots of links, Sydney Gore explores “why everyone suddenly wants to be perceived as well-read.”

World Architecture Community features “WAC’s Top 10 Architecture Books of 2024.”

Domus features “10 books to read during the holidays.”

“From brutalist buildings in Eastern Europe to private homes on the Amalfi Coast, architecture is the focus of several volumes” in Air Mail’s “Best Coffee-Table Books of 2024.”

From the Archives:

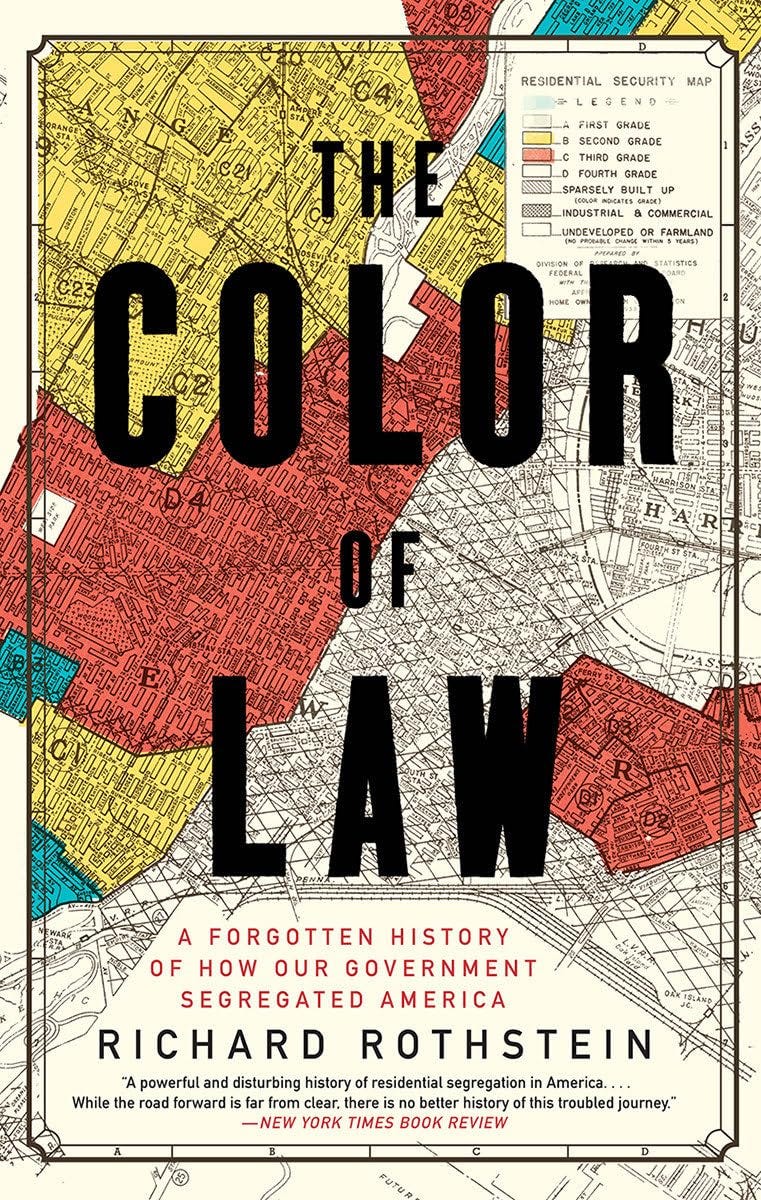

For a while I had an “Unpacking My Library” blog, which allowed me to say something about books that wouldn’t have been featured on my architecture (book) blog. One such book was The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America (Liveright/Norton, 2017) by Richard Rothstein. Here’s what I wrote on that blog, in early 2018, I think:

“I often don't pay close attention to year-end best-of lists for books, since most of them focus on fiction, which I rarely read. That said, I do take note of non-fiction lists, and one book that was on many such best-of lists last year was Richard Rothstein's account of housing segregation in America. Previous to reading it, I'd heard about redlining and the maps (like the one on the cover) that they refer to, but I was as guilty as most Americans in not having enough knowledge of this ‘forgotten’ history. (I actually wonder if ‘forgotten’ in the book's subtitle should be replaced with ‘untold.’) Rothstein's history is deeply researched (with many long footnotes), clearly told, and one of the best books I've read in recent years, well worth all the year-end praise.

“In The Color of Law Rothstein provides evidence and stories of how racial housing segregation in the United States last century was mandated by the government. It was, as he describes it repeatedly, de jure segregation rather than de facto segregation; the former is in accordance with law while the latter arises from social factors. But Rothstein doesn't just tell a history, he also argues for some fixes (none of them easy) for the lasting effects of residential segregation. Perhaps knowing the controversy of his book's subject and the difficulty in people swallowing his fixes, he even supplies a section of Frequently Asked Questions — and clear-headed answers — at the back of the book. It's a history I wish didn't exist, but one that needed to be told, in just the way Rothstein did.”

Another older book related to this week’s Book of the Week is Zoned Out! Race, Displacement, and City Planning in New York City (UR Books, 2016) edited by Tom Angotti and Sylvia Morse. I reviewed the book on my blog in 2019; a taste:

“Zoned Out! […] features six chapters on the role of zoning in displacing low-income communities of color in New York City. The first and last chapters come from Angotti, a stalwart of community-based planning and an enemy of REBNY and YIMBYs throughout the city. In the first chapter Angotti spells out how zoning is legally defined and is used by the city at the behest of ‘the land market’ to promote new development: in 140 areas by Mayor Michael Bloomberg and 15 to date by his successor, Bill de Blasio. The last chapter focuses on community-based planning and, in concert with the first chapter, is aligned with his assertion that planning is not practiced in New York City but needs to be. (In between is a chapter on race and zoning, and three chapters with case studies of zoning displacement in action: in Williamsburg, Harlem, and Chinatown.) […] With zoning so far entrenched in the machinations of city government, real estate, and architecture, reorienting it toward more just ends seems insurmountable. Zoned Out! is a perfect place for pro-planning progressives to prepare their protestations.”

Thank you for subscribing to A Weekly Dose of Architecture Books. If you have any comments or questions, or if you have your own book that you want to see in this newsletter, please respond to this email, or comment below if you’re reading this online. All content is freely available, but paid subscriptions that enable this newsletter to continue are welcome — thank you!

— John Hill